A nameless woman is released from hospital following an “episode” whose nature and effects remain unspecified. Taking up work at her family’s fish market, she meets a colleague known as the Turk, who has a neglected baby and a friend involved in “low-level criminal enterprises.” They enter a relationship of sorts. The narrator sees a strange mythical cat appear around town; people begin dying in improbably violent ways. When the situation turns dangerous on Christmas Eve, she wanders out through the snow as neighbours watch from afar, silhouettes that eventually lose interest or annoyance and dim themselves away. “In the year I’d been back from the hospital,” the woman says, “my brothers never introduced me to their wives or children. It only occurred to me that night that there might have been a reason for this.”

This is the premise of Michael DeForge’s new book, First Year Healthy, or at least what initially seems to be the premise. Although the entire story only runs to several dozen pages—that “graphic novel” tag in the classification is like calling one of Lydia Davis’s pieces an epic poem—I found myself cycling through the imagery again hours later. DeForge is a widely admired young cartoonist (and Hazlitt contributor) who became one without courting visibility through grander projects; last year’s Ant Colony was his first book-length narrative. (He once destroyed another half-complete graphic novel, dissatisfied.) DeForge tends to work in shorter, serialized forms: He recently launched a Patreon subscription page, giving readers who pledge a few dollars one short story per month. The brevity often makes each strip even more discordant, like a spectre you’ve sworn flickered across your vision.

Amongst all of DeForge’s miniatures, First Year Healthy has the crispest precision, a bladed and brittle severity. Information haphazardly exposes itself. Every page exists as a separate illustration, with typewritten, affectless, numbed captions. The narration reminds me of David Goodis’s noir novels, where action occasionally interrupts haggard internal monologues and pleas for help move limping towards their target. DeForge’s prose has a similar posture of sublimated desperation: “Hours passed. We spent this time together in almost complete silence. We eventually started eating some of the food the townspeople had left. He kept his gun fixed on me throughout the meal. Eventually, he fell asleep. I cut his throat, took the child, and ran out of the apartment. I could hear him choking and gurgling as I put on my boots, but I wasn’t sure if the wound I delivered was fatal or not.”

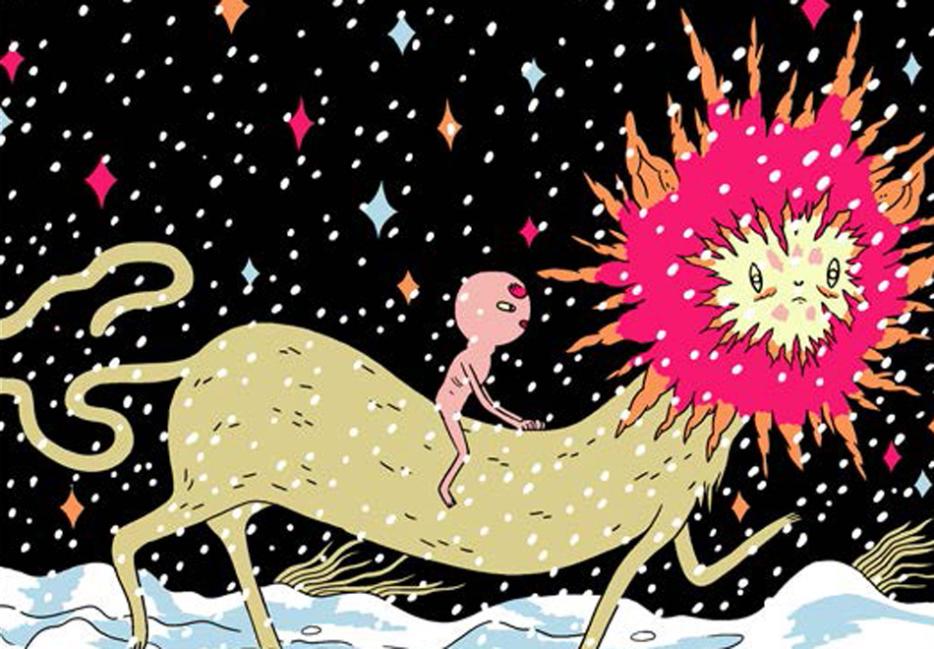

Composure is so often the meeker kind of feint. First Year Healthy’s unyielding format heightens the strangeness of the images by trying to impose order on them. Sometimes I call what DeForge draws now “stylized,” but that might burden his pages with too much logic. The unnamed woman’s hair looks like something she found on the street and shoved underneath her hat. When she dines with the Turk’s malevolent, panicking friend at gunpoint, the flowers of the tablecloth could be phasing in from a different plane of existence. And that cat-creature she dreams about has the mane of an exploding star. DeForge uses colours like he wants to inspire new names for them—I still think of one particular malachite green from Ant Colony as Graveyard Lawn. In First Year Healthy, harsh lightbulbs shine beneath a gangster’s skin; a brick wall is several dozen pieces of unchewed gum. The “holy cat” prowls a winter landscape, and the sky behind it ribbons like melted sherbet.

Like Ant Colony before it, First Year Healthy was originally serialized online. I don’t know how much DeForge altered his plans in the course of that, if at all, but the act of collecting his story has recut it: The comic I first clicked weekly as a series of discrete tableaux now reads almost recklessly fast. Like an episode. In this and maybe no other aspect (aside from some random violence), it resembles Mickey Zacchilli’s RAV, which began life as her self-published comic series before getting repackaged akin to manga paperbacks. “Her story is basically a chain of occurrences following a bunch of funny characters around as they meet new people and have arguments and occasionally fuck each other and generally sort of participate in a community, roughly,” the critic Joe McCulloch wrote, “but this variant reads really, really, really fast, expertly guiding your line of sight through these stretchy, decompressed images, surface-level ‘noisy’ yet as intuitive as anything else you’ve seen.” First Year Healthy frustrates your intuitions.

So did the narrator really leave that hospital and escape a scarred thug, primarily because he vanished? Is the majestic cat a figment of her mind, or is a reader’s mundane distinction between them the delusional part? None of those questions seem too important to me, not as much as the visual parallels between woman and beast, suggesting the disassociation that emerges half-recognized from various forms of madness. My friend Sarah Nicole Prickett once recalled the onset of bipolar disorder: “There comes a time when the way you are is not just the way you are, but also the way you might die. There arrives at that time a word for what you said or hoped was indescribable, a diagnosis for your lure. Always there were moods you had that others did not, moods that were your organizing principle. Now they become your undoing. You weren’t wrong to think nobody else was like you. Not many people are. Almost nobody would want to be, and that’s where—in your wilding moments—you were wrong.”