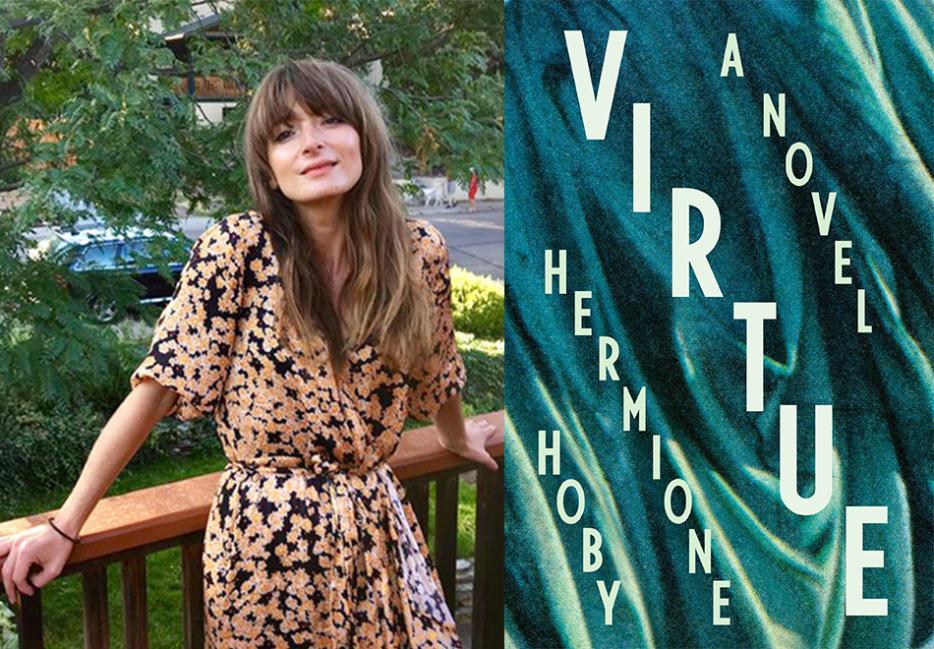

“I wanted badly to be good; I wanted desperately to be liked. It was easy to confuse the two.” The narrator of Hermione Hoby’s new novel Virtue (Riverhead), a half-formed young man called Luca, takes up an internship at a much-acknowledged literary magazine amid mass revolt. Above the battles in the streets, piety and complicity mingle uneasily. He grows enamoured with an older artist couple from that orbit, Paula and Jason, becoming their own object of fascination. Installed at the pair’s summer home, Luca comes across a newspaper piece about Paula’s latest show: dolls mimicking family life inside domestic miniatures.

Hoby’s debut Neon in Daylight had that dizzy gait of somebody trailing behind a crush; the romantic flights of its characters always risked stumbling into the gutter. Virtue manages a more sceptical eye even while inhabiting a single narrator, as Hoby reveals her gift for describing excruciating social situations: The gallerist visibly straining to recall your importance, the patrician editor proclaiming let us see what can be done, “an invitation that now impressed me for being simultaneously inclusive and egotistic.” Whatever distance Luca finally does find from that world arrives as desolation.

Chris Randle: You're calling from Boulder, right?

Hermione Hoby: I am, yeah. Are you in Brooklyn?

Yeah. It was apocalyptic a couple of nights ago and now it's a beautiful fall day.

I really hope you're not in a basement apartment. How was it?

It was fine for me personally, I'm a few floors up, but there was so much—the last I heard a dozen people had died, transit shut down. On the night of the storm itself somebody I know was at Newark Airport, and they got trapped there for hours, because there were no flights, and the complex was slowly filling up with water. During the last big storm a couple weeks ago, I was heading to a friend's going-away party, and when I passed through Metropolitan, the G train stop, it smelled like raw sewage. All this infrastructure is rotting out.

Yeah, it seems like a lot of people even in New York had no idea this was about to happen. My friend texted me and said, "My basement's flooded," and I was like, oh no, her pipe's burst, and then looked at Twitter and was assaulted by these apocalyptic images. I don't know if you feel this too, but I find one of the difficult things (among many) about being alive right now is this sense that nowhere is exempt from climate disaster. That if there were a place that was somehow environmentally safe, everyone would move there and it would no longer be safe, you know? It just rained here and the skies are clear but there's been wildfire smoke for days. My partner just ran out to get another air purifier—there was that sense of, better get one before they run out, and I hate finding myself in that mentality, that scrabble to protect oneself.

I think that's what's behind the whole Peter Thiel thing—this right-wing fantasy of moving to New Zealand.

Yeah, exactly. Just hunker down.

It's applying that capitalist logic to life itself.

Absolutely. It's so depressing. I was having this conversation with some friends recently: what do we do and how do we survive? There were four of us, two men, two women, and the guys were like, you prep, you get cans of food or whatever. And me and my female friend were like, "Why would you want to survive in such a world?" [laughs] What would be the incentive to stay alive in Peter Thiel's world, a world of squillionaires hunkered down in their cabins and the rest of us fighting each other to live?

That kind of dovetails with the first thing I wanted to ask, which—I don't know where you're from originally in England, but Boulder is a very different landscape, different from New York as well, so I'm wondering if that's affected the way that you write at all.

I'm from the southeast London suburbs, and I was just there recently, finally seeing my family again. It felt very—I hope this doesn't sound snotty—it felt small to me: I fear I've been spoiled on these extraordinary mountain vistas. I think it felt, small, too, in a miserably post-Brexit way: inward-looking, cramped.

I don't know how it's changed me as a writer; I know it's changed the way I feel and think. I feel slower, I feel much more relaxed. When I go back and visit New York, I wonder how I ever got work done, because it's so noisy. It’s a place of intense stimulation and excitement, and Boulder is of course a great deal sleepier, but it's been wonderful to be in a place that's quiet, and full of natural beauty. This is the first time in my life that I've had a room of my own to write in, and it makes such a difference to go into a space, close the door, and know that space is yours, a designated space for work. It makes me feel incredibly fortunate. I guess the way that being here has changed my writing is just having an office, which seems like an unromantic answer [laughs]. I'm writing something now which is not set in Colorado, so maybe my Colorado novel is to come. One of my friends keeps insisting I write a Western.

Both of your novels are almost infatuated with New York City.

They really are [laughs].

I guess you were still living here when you wrote the first one, but with Virtue, how did you summon that back up again?

You mean summon the sense of New York while I was here? Yeah, I feel like I sort of became myself in New York—it's a foundational place for me. I had lived in London-proper for a couple of years after graduating, but I never felt the sense of... it's not ownership, it's more like, oh, this place gets me, and I get this place, the way that I felt as soon as I arrived in New York. I was just like: here it is. I think I moved to New York when I was 25, which is an impressionable age, and I felt like the city made me who I was.

So it's still very fresh and accessible. Neon in Daylight is very much a New York novel, but with this one I didn't think I was writing a New York novel at all. To me the setting was sort of incidental, but the dynamics of the city certainly feature, and the beginning and the end are set in New York. I suppose with this one I felt like what was driving me wasn't place so much, as it was in the first book, but character. As soon as they'd become real to me, the engine was there. I didn't have to conjure the city consciously, the thing that was driving it was these people.

It's kind of like, in Neon in Daylight the setting is its own aesthetic, and in this one it feels more sociological.

It's really gratifying to be read like that, because I felt like I wanted to write a more grown-up novel than the first one, in which New York was not just, as you say, an aesthetic experience, but a place that was politically fraught as well.

I was also curious about the shift in perspective, because your first book has a third-person narrator and the characters get introduced in this almost symphonic way, one by one, circling around each other. Whereas Virtue is first-person, more of a monologue, and I'm wondering why you chose to switch it up.

I will answer the question properly [laughs], but the preface to the proper answer is that, whenever someone asks about choice, I always feel like, ah, it's not exactly choice. With this one I just had his voice in my head, unbidden. It was like this voice in the aether had chosen me for a moment, just jumped into my brain as its host. And then of course there was the choice to stick with it, and the choice not to shift into any other perspective, but Luca just seemed this compelling... presence to me. I also think there was something liberating about knowing that there would be no possible autobiographical confusion. I am absolutely not a young dude from Broomfield, Colorado.

I think so much of writing is about shedding self-consciousness, following intuition, and allowing yourself to be strange and odd. To dodge the expected thing. By that I don't mean that people were expecting something of me, I just mean, in the work itself. I want it to be unpredictable, surprising, which is to say honest, and perhaps the vehicle of a young man as narrator made it easier to do all those things, because it was already removed from me. I was already inhabiting something strange and different. I had a lot of fun being a dude for four years, my shadow life as a young man. It's an act of madness to inhabit another person, but a fun one.

I think there's also narrative contrivances that are kind of inherent to fiction, and first-person can lay them bare in a way that's sometimes obvious and annoying, like, oh yes, I just happened to find this cache of letters or whatever. But sometimes it also makes the whole design clear in a striking way.

Yeah. I think one of the reasons I deployed this frame narrative, in which he's 34 and recollecting being 23, is that it seemed a way of doing first-person with some of the benefits of third-person, in that there was a sort of authorial voice working through the immediate voice of the young man—in other words, a double consciousness to the narration. It seemed to offer a malleability, whereby I could keep shifting, even within the space of a sentence, between the more reflective, older Luca and the young Luca who’s gauche and ardent and overwhelmed by the world.

I was thrown by that near-future vantage point. Was it always framed that way?

You know, originally it was much further in the future, like, a moment of facing mortality. I couldn't make it work, it just seemed cheesy and overblown, and I was like, "Well, if this moment in his youth was so important, why would he only be telling the story now, when he's 85 or whatever?" I kept trying, but I couldn’t convince myself. And then I thought about The End of the Affair, where the distance between what has happened and the point of narration is narrower, and that seemed emotionally truthful. As in, enough has changed in Luca’s life that it feels like a different time, but there's still this intense emotional residue. It seemed more plausible that he would be revisiting this time and thinking about it. I guess I had this sense that he's narrativizing this moment almost in an exculpatory way, it's self-mythologizing while knowing, as this older man, that self-mythology is a feature of youth, and that way no wisdom lies.

And there's the little echo of that original framework, one of your most extraordinary passages, in Luca's reverie of his own deathbed.

Oh, yeah! I feel like I'm admitting all my secrets now, but that originally was just his deathbed, straight up. And of course it was so corny, I couldn’t make it honest. My best friend read this very bad passage and generously, helpfully said, "This is almost like his fantasy of himself," and I was like, "Wait a minute, that's what it is!" This is him writing a fantasy deathbed scene, badly. It's a kind of false ending, I guess, one to do with wishfulness and self-fashioning.

Yeah, it definitely fits with the... gnarled masturbation that he does, literally and figuratively.

That's an intense phrase. I don't think you're wrong, but wow, yeah [laughs].

I really treasure good writing about clubbing—I didn't fully appreciate all the uses of dance music until my early twenties, which I think is true of Kate in Neon in Daylight as well. And I loved that passage where she's idling against the edge of the club: “It was a wall she found, a sallow wall, damp with moisture, but as she set her back to it the floor started to tilt, gently, some sick tease. When she blinked, she wished she hadn’t: everything refracted and blurred, trailing echoes of itself, woozily haloed in gold.” Is that a similar experience that you had?

Well not that precise experience, no, but also I hear you say that and I'm like, oh my God, I'm so old, once I did drugs and went to clubs [laughs]. Although I guess none of us have been doing that over the past year and a half—for very good reason. My experience was probably pretty standard for people of my demographic; I had ecstatic, revelatory-seeming nights, a few in London, many more in New York. New York always just felt way more fun to me than London, still does. Like, a greater sense of possibility: a spirit of optimism and permissibility, rather than the defeatism and inhibition I perhaps unfairly associate with the UK. That novel feels like ancient history to me now—it was very much a novel of my twenties—but I do remember that one of the things I was thinking about was intoxication, in all its forms. You know, what was real and what was cheap and illusory.

If you have what feels like a transcendent experience and it's been induced by taking ecstasy, is that any less meaningful than something I'm more likely to do now, which is hike to the top of a mountain at dawn? Or not at dawn, I need my sleep. Anyway. I think the answer is no, they're both valid—but I'm sure you've seen this too, we probably know a lot of people, we probably love a lot of people, who have become trapped in intoxication. So I don't want to be sounding blithe about what can be life-limiting or even life-ruining, but I had fun [laughs]. I hope that fun may return to us at some point. I do miss dancing.

With any kind of intoxication there's this delicate balance or tension between feeling embodied and feeling weightless. I was at this friend's going-away party a couple of weeks ago, you know, molly-fied, and I didn't realize how much I had missed standing with people outside, feeling the individual beads of sweat on your skin against your shirt, hearing the muffled pulse of music coming from inside.

Yes! That's beautiful.

And when all of that is aligned it's just the best feeling. I think that's when I feel most at home in a body. But when those are misaligned, you don't realize how awful you're being or stumbling around blackout drunk, rampaging, unaware of what you're doing—

You're right, it's a delicate thing, and I have a horror of being insensitive to other people, which is probably why I haven't gone totally crazy on intoxication, because that's just the worst. But it's exciting to see how much is being written about in terms of psychedelics, it seems like so many people are coming round to the therapeutic effects, whether you're taking them recreationally or in a more controlled way. A friend of mine right now is doing this ketamine therapy in a totally legit, controlled way, and it seems transformative. I'm like, I need to do more psychedelics before I die. Mushrooms are legal in Colorado, so I should get on it [laughs].

Weren't they one of the first states to legalize weed as well? There's dispensaries, right?

Yeah. Ben, my partner, sometimes jokes, "If my 16-year-old self could see me now, living in a place where weed is legal, he'd be so disappointed in me for not being totally baked every day." I think weed isn't cool here now because it's legal.

The last time I went home to Canada, where's it's legal nationwide, there's signs at the airport like, "Please declare your weed paraphernalia." I think Canadian travel regulations are the most uncool you can possibly get, so.

It would be great if all drugs are legalized in our lifetimes. I'm sounding like some kind of crazy drug advocate, but maybe I am [laughs].

I feel like the great ambivalence at the heart of Virtue is complicity—have you read The Line of Beauty, the Alan Hollinghurst novel? There's a line towards the end of it, where a member of the Tory MP's family the protagonist has been living with says, "We always supposed that you understood your responsibilities to us." Embracing somebody and throttling them at the same time. And the characters in your book, they don't have that sort of political power, or even all of the wealth, but they are very comfortable, very much ascendant in the culture industry.

Absolutely.

I guess I'm wondering, how do you think complicity operates in that particular world, as opposed to, like, "Yeah, I'm just hanging out with these grotesque plutocrats and Margaret Thatcher."

It's really interesting that you say complicity. A novelist friend of mine read this book just before it was published, at the same time as Sally Rooney's novel [Beautiful World, Where Are You], and she's like, "You and me and Sally were all writing about the same thing! It's complicity!" I don’t mean to arrogantly align myself with Sally, who’s such a fucking genius! But what I mean is, I don't think you or my novelist friend are wrong. I guess one of the questions that was really driving me from the start with this (outside of the novel, too; it'll be troubling me for my whole life) is how to live an uncompromised life in such a deeply compromised world. And of course it's not possible. Like, here's my iPhone, people in China maybe died to make this. If we investigate almost any part of our lives, and follow the trail, it so often leads to subjugation and unconscionable crimes against humanity [laughs]. I don't mean my laughter to be glib, it's just the absurdity of—how do you try to be a good person when the world is set up in this way? Should Paula and Jason, if they actually care, just give away all their money?

And I suppose this ties to the question of—I think Luca makes it explicit quite early on in the book—the small world and the big world. This is actually how you and I kind of started this conversation. If you're Peter Thiel, you make your small world, you retreat to your bunker and just look after yourself and adopt a fuck-everyone-else mentality. And that, of course, is pure hell on earth. I probably sound pathetically idealistic saying this, but I want us to live in a world of mutuality and care and community, one in which we all acknowledge and honor our interdependence. When the pandemic began I had such a naïve thought along these lines: that this global disaster would wake us up to our commonality. So the big question for me was, how much attention does one pay to the small world, the world you can manage, your immediates and your home and your small community, and how much do you look outward to the civic and the political and the national, the international. I think Zara has chosen the latter, she's on a mission and she can't really form close bonds because of that. Whereas Paula is like, "Well, I've got my kids, and it's up to me to bring up these kids and make my art and that's what I'm doing." Luca is torn between these choices.

All of us could be doing more, but we also I think have a duty to our own happiness. Particularly in those first years of the last administration, there was just this constant feeling of, am I doing enough? I've set up my donation to the ACLU and RAICES, but could I afford more? Should I be volunteering more? If I miss a march to go see a movie, does that make me a bad person? So we're all complicit. I mean, maybe there are a few people living off the grid, that's not exactly complicity, but it is a refusal of the world. The challenge is to find a way to be in the world that doesn't feel so desperately morally compromising, and I don't know how to do that. I'm trying [laughs].

And a lot of these galleries and little magazines and other institutions love to say the right things even as they also love union-busting, or not paying their workers enough to live on.

Totally, I know. Last summer all these huge companies were loudly proclaiming "we stand with Black Lives Matter" while quietly paying the women who clean their offices, predominantly women of color, below minimum wage. We live in such an age of presentationalism when it comes to politics, as in, “let’s make it look good”—never mind what's actually going on beneath the surface.

Do you remember when one of the Whitney Museum's trustees got forced to resign, for being an evil—his police-equipment company was actually called Safariland, as if he were some pith-helmeted colonist. Several writers published a collective statement against him, with a line I just returned to: "The rapacious rich are amused by our piety, and demand that we be pious about their amusements."

Mmm, that's a very good line.

And I love how you describe that whole world in the first half of the novel, the countess who funds the little magazine and the elderly WASP editor. When you're writing things like that, obviously they're not precise analogues of anyone, but there's also a lot of... grist for that particular mill. Do you ever find yourself consciously filing details away...?

Oh yeah, I'm just a glinty-eyed little magpie all the time. The crazy thing about fiction is that, by the time you've written it, you actually forget what was stolen from reality and what was purely invented, such lines become blurred. One friend sent me a beautiful email about the book, it's an email I will treasure, but I had forgotten that there is a scene—you know when they go to the square dance in Maine? I had totally forgotten that I'd sort of taken that from a real experience which I’d shared with her, not in Maine, the details changed. She said something like, "You were just hovering above it all the whole time," which is a nice thing to say, but it's slightly sinister too [laughs].

In transmuting reality into fiction, the fiction necessarily becomes more real to you than its originating material. My first years in New York, I was lucky in that my visa status was such that I couldn't work for American publications. So in a way this lent my social interactions a kind of... innocence, I guess? If I was talking to someone at a party, it wasn't like trying to get published in whatever magazine. I was just experiencing it in a slightly anthropological way, which I think all fiction writers do. It's fascinating to observe human beings.

One part of Virtue I became slightly obsessed with was Luca's... sexual indeterminacy?

Very well put, yeah. I had been describing him as a straight white guy, and then I was like, well, mostly straight. Straight-ish.

There's that wonderfully oblique line about his later encounter inside the infinity room with the Japanese artist. It seems pretty clear that he's not straight, but maybe too much of his identity is bound up in that. Yet at the same time he's very clearly sexually obsessed with both halves of this artist couple. And they're kind of encouraging it, pushing and pulling. I guess I don't really have a question...? [laughs]

Yeah, let's just talk about that [laughs].

Is that something that emerged while you were writing the book?

I had a sense from the very beginning that he would be obsessed with these two. And then as it went on I wanted him to be more obsessed with Paula, or at least the sexual attraction was more pronounced with Paula, but that didn't preclude some sexual current between him and Jason. So often the choices, because these were choices, were about it not being precise. I didn't want anything to be simple. So I didn't want it to be that he's equally sexually attracted to these two people, I wanted his sexuality to be a little mysterious. I want it always to be complicated, uncertain, because that to me seems more truthful. That's the kind of fiction I want to read, mostly.

I wanted to apply that principle to pretty much every character in every situation. For example, with Zara, she is this young woman of extraordinary principle who at one point rails against the heternormative beauty industrial complex, but I also wanted her to paint her toenails, you know? It's like, there are these minor, petty, inconsequential hypocrisies within her way of living, because she's a human being. Similarly, I wanted her to maybe be a little bit mean as well as smart. I wanted everyone to feel as real as they possibly could. And that, to me, felt like trying to dodge the received or the even vaguely stereotypical at every turn. But of course the problem with that is that you have to be believable, too, and I think it's a fine line to walk between cliché and the received on one hand, and the improbable or outlandish or completely unrelatable on the other. That was one of the many challenges [laughs].

I can't speak for straight people, but there's definitely couples that I know where—they're not inviting me to their beach house and I'm not becoming obsessed with them or anything, but I've definitely found myself going, am I attracted to both of you, or am I attracted to an idea of your life?

Totally, exactly! I've had that too—it's like, I find you both sexy, but is what I'm finding sexy your couplehood, your life, or is it you as individuals? And very often I think it's the couplehood, two people who are really into each other and have extraordinary chemistry, they can often become attractive to you, because you kind of want to be them, I guess. Or at least be in on that energy in some way.

I remember reading that Diane Arbus had this fantasy project where she would go into people's houses and photograph them while they slept. Or even when I'm catsitting, it's not like a fetishy thing, but I love seeing how other people live, you know?

Oh my god, me too. When I was doing interviews, it would thrill me when the interview was at their house, because I'm just so curious. I interviewed Toni Morrison and I got there and I really needed to pee, and she was the warmest and realest, just a force of all that’s good. She was like, there's the bathroom or whatever, and I was like, oh my God, I'm in Toni Morrison's bathroom. But it didn't need to be Toni Morrison, it's not that she was Toni Morrison, it's just that thrill of being in someone else's space, seeing how other people live. I think that's what drives me as a novelist, the fascination with other people. I'm just ravenously nosy all the time.

Do you think if Luca ran into either half of that couple individually, would he still have become obsessed in the same way?

I think not to the same degree. It is about the heat of them as a couple, as well as who they are individually.

It's almost like, the whole domesticity of it feels very conventional on one hand, but then there's the third party making everything faintly perverse.

Absolutely. I think you kind of alluded to this earlier: he dynamizes their relationship. They're getting off on knowing that he's awed by or attracted to the two of them. The erotics are triangular.

There's that passage where he feeds a handheld ice cream to Paula...

Oh yeah, I wrote "Magnums," and my wonderful editor Cal was like, with a little blushing face in the margins, "Do we need to specify ice cream, not condoms?"

He's simultaneously wrapped up in the physical response and watching it happen.

Exactly. That's narration, right? To traduce Wordsworth, it's horniness recollected in tranquility. This goes back to what we were saying about the dual voice, the simultaneity of the self and the narrated self.

Virtue uses Cy Twombly's paintings as semaphore for the flush of infatuation. What elicited that association for you? Is there any other art hanging over the novel in a similar way?

So, this will sound like a bafflingly oblique answer, but I often think of John Jeremiah Sullivan writing about Whitney Houston. It was just a brief thing after she died, and at some point in this highly thoughtful, intelligent piece of critical appreciation, he says something like, “her voice was so good.” The sentence is that simple, unadorned and, in a way, gorgeously thoughtless. It seemed to be a humble recognition of the way in which some things—certain paintings, infatuation itself, the miracle of Whitney’s voice—are beyond intellection. A person can cerebrate over abstract art, for example—a worthy enterprise!—but when they get in a room with a Twombly canvas they might discover thinking goes out the window. The novels I love most are dynamized by this tension, between the felt and the thought.

What are you working on right now?

I'm working on... well, I hope it becomes a novel. Right now it’s just a messy Word doc, so I feel a bit superstitious about declaring it to be a third novel, but I hope that's what it becomes. It involves a British man who becomes a Hollywood actor…