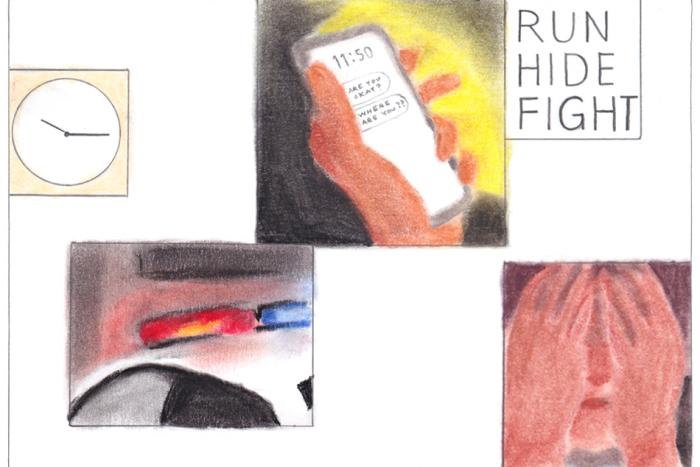

What does a campus shooting feel like?

When Wanda bought the house, she didn’t imagine that anyone in the community would recognize that she and Lynn were queer.

Latest

People love John Samson Fellows’s music. He doesn’t want to make it anymore.

When Wanda bought the house, she didn’t imagine that anyone in the community would recognize that she and Lynn were queer.

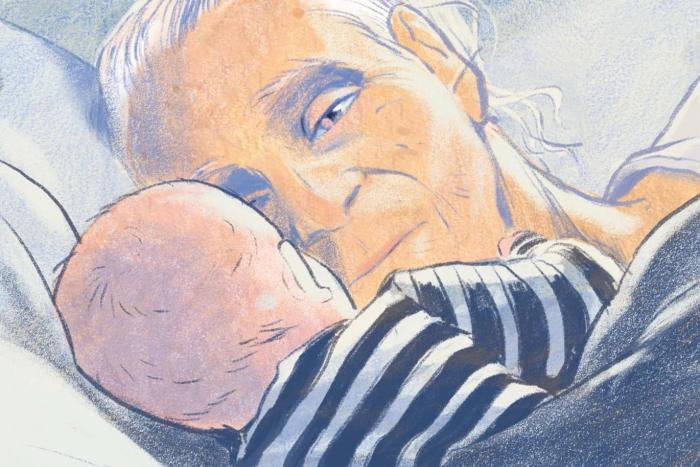

The baby had come from a place none of us could remember. Our grandmother was headed there.

The author of Mother of God discusses the limitations of realism, Frank Bidart, and the anguished duality of shame.

Standing in the wreckage of these spaces unlocks a sensation people often crave, but can’t name.

It’s an imagined past, a pastoral imaginary, an alternate timeline in the multiverse.

“Bird,” he cried, “I come on behalf of the emperor. Your voice is all anyone speaks of.”

She stops to look into her mother's face. It is smooth and blank as a stone. Nothing emerges; nothing shifts.