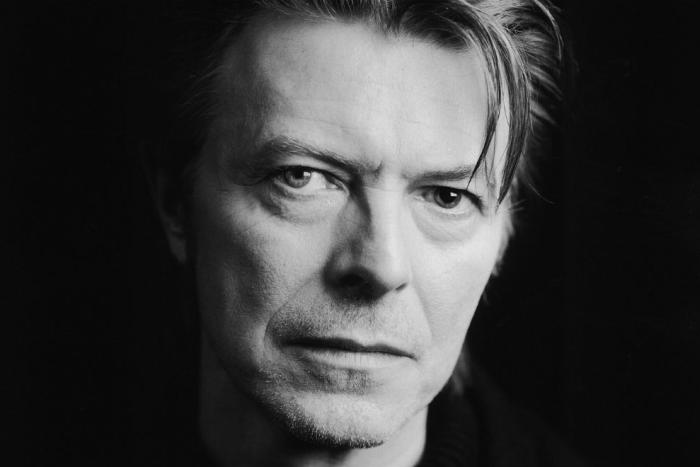

David Bowie was never the most relatable pop star. He was almost deliberately the opposite: shape-shifting, ironic, glib, versatile, dramatic, and above all else, magnificently self-aware at every single turn. He touched on queerness, the occult, the avant-garde, blue-eyed soul, and electronica while simultaneously keeping any categorization at arm’s length. It’s tempting to say that, above all else, David Bowie was about that playful, even manipulative, distance between artist and audience.

About a week ago, a friend and I were discussing rock death over Indian food. When Bowie came up, we drew a blank. What, if anything, would we feel? Would there be a sense of loss?. Bowie is one of the most influential and important musicians of the twentieth century; he leaves behind a staggering body of work that, for so many of us, is rich in personal associations. But he was so lofty, so singular and yes, so alien, that for him death seemed impossible. David Bowie was too smart, too shifty to ever succumb to something so ordinary. Either he would find some way to subvert the problem or simply thumb his nose at mortality and continue on his merry way.

That’s what made David Bowie a titan: He was ingenious enough to both follow his own path and, at every turn, carve out a niche for himself in an ever-changing pop landscape. Bowie wasn’t so much inventive as he was joyously opportunistic. Like Miles Davis, to whom he’s often compared favorably, Bowie would often pick up on sounds or trends that belonged to others and then catapult them into the mainstream. His popularity was circular: Because David Bowie was always introducing new ideas to a wider audience to prove his own relevance, he remained eternally, inscrutably relevant, no matter how far afield he wandered. He was, in the most literal sense, the vanguard of pop.

But as much as Bowie borrowed and benefitted from the likes of Iggy Pop and Brian Eno, there was a there there. Bowie may not have had a soul, but he had heart (or maybe it was the other way around). Everything he absorbed was then refracted back through his unique sensibility, one that was at once and in no particular order sentimental and dead-eyed. With Bowie, you could never tell if you were being lured into feelings, if the whole thing was an elaborate prank, or if Bowie’s music was pulsating with emotion despite all its cunning and pretense. It almost doesn’t matter. Bowie’s music means so much to so many of us that artist intention seems beside the point. “Soul Love” projects warmth even if it’s meant as kitsch; the melodramatic “Life on Mars” soars; his over-the-top version of “Wild is the Wind” still cuts to the quick.

Bowie isn’t whatever you want him to be. Bowie is simply everything.

That’s why it hardly seems appropriate to mourn David Bowie as a flesh and blood human being. As a person, he was a riddle, a suave enigma who never quite cared about connecting. He could put on a show with the best of them but it was hardly intuitive; Bowie was not about to expose himself in that way. Yet the music he leaves behind has a life all its own, a life largely attributable to the way it has fit into our own experience. Lou Reed’s death felt like a personal blow because the Velvet Underground hit so many of us at a formative age. Bowie, by contrast, was seemingly there all along, casting a long shadow over our lives.

My favorite Bowie record is Station to Station, an unspeakably weird, coked-out opus that brims with (delusions of) grandeur, quasi-fascist trappings, and references to a grand mythology that only the man himself understood. Even more than the Bowie-Eno collaboration Low that came after, it’s Bowie as deeply alienating, positioning himself for maximum shock value even as he retreats into an inscrutable inner sanctum—which, at the time, was a mix of utter turmoil and almost unmatched confidence. It would have taken nothing less to pull off Station to Station, which feels like a hollowed-out musical wasteland repopulated by ghosts, robots, goblins, and crack session musicians. It’s a jarring experience that can set your teeth on edge, but it’s also, at various times in my life, been everything from inspiring to insidiously funny. Bowie isn’t whatever you want him to be. Bowie is simply everything.

Today, though, as I try to make sense of Bowie’s passing and the legacy he leaves, I’m stuck on Hunky Dory, by far his most vulnerable record—especially the A-side. “Changes” is blithe and zippy, a good-natured gloss on a future yet to come. “Oh You Pretty Things” is no less warm, this time celebrating misunderstood youth; “Eight Line Poem” is abstract as lyrics come but you wouldn’t know from Bowie’s heartfelt vocals and Michael Ronson’s dainty blues licks; the aforementioned “Life on Mars” is a small miracle, an overwrought, aching melodrama that effortlessly draws you in; “Kooks” is a downright affecting song about becoming a parent; and “Quicksand,” despite its Nazi references and obtuse language, is all piercing self-examination.

That run on Hunky Dory is by no means without humor, irony, or the madcap touches that made Bowie such a freak. But what we get with this sequence of songs is a real sense that David Bowie had a life, had experiences, had words he needed to set to music and put out into the world. That understanding, as much as the record’s lush melodies and folk-rock textures, is why Hunky Dory stands out from the rest of Bowie’s classic albums. It’s Bowie as someone with plausible needs and wants, an artist whose impulses come from somewhere other than a place of arch-conceptualization.

However fleetingly, Hunky Dory is Bowie as one of us, the perfect way to mark the end of a life. It’s also the lesson at the heart of his music: No amount of artifice or self-conscious creativity can allow us to fully escape our feelings, our humanity. It may seem like a failing of everything David Bowie tried to accomplish. But in the end, making us feel so much in spite of himself was Bowie’s greatest triumph.