Welcome to Mind in Bloom, a column deconstructing current events, music and art.

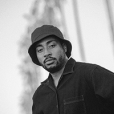

An artist whose first public act was to eat a roach in the “Yonkers” video, Tyler, The Creator’s default mode has always been to provoke. Tyler was possessed by an uncontrollable urge to shock from the very beginning, the first emcee to evoke the situationist verve of Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren. His croaky, sonorous voice seemed as if it couldn’t possibly be coming from the gangly Black body that we were looking at; that authoritative bellow emanating from him had to be another troll job, a ventriloquist trick straight out of his hero MF DOOM’s book.

But it was really him. The music industry was confounded. What this kid from Los Angeles said on his songs was often beyond the pale. Like Eminem before him, he rapped about rape for laughs and gleefully punctuated his verses with gay slurs. There were moments of publicity that must have made Johnny Rotten smile, such as when he was banned from Australia, New Zealand and the U.K. for “posing a threat to public order” with his violent lyrics. Tyler pushed everything he did to the extreme, an edgelord who insulated himself from bountiful criticism through the undeniable greatness of his output. Starting out with harshly minimal self-produced beats and unprintable lyrics, Tyler has grown and matured as an artist with each release.

His imperial phase began with 2017’s Flower Boy, the album on which he first opened up about his sexuality and began to soften the edges of his sound. Following Grammy wins for Best Rap Album with IGOR and Call Me If You Get Lost, his place in an industry that long didn’t know what to do with him became solidified. Tyler showed himself to be an Album Artist, a brilliant curator with a curious ear for atypical juxtapositions, such as placing ’00s mixtape-era adlibs on the same album as breezy jazz instrumentals with CMIYGL.

On 2024’s Chromakopia, Tyler shows himself to be the same person with the same impish impulses. But his transgressions present themselves differently today. Where he once tended to shock through the violence and ugliness of his rhymes, he now attempts to stun the listener with his uncommon openness about his personal vulnerabilities around relationships, aging and parenting. Previously criticized for misogyny in his songs, he throws down the gauntlet at the rest of the rap world with his intentional platforming of women rappers like GloRilla and Sexyy Red on the rumbling “Sticky” and a song-stealing turn from Doechii on “Balloon,” not to mention the various samples of his mother’s voice throughout the album.

Hip-hop has struggled over the years to paint a complete picture of the female experience. Either hypersexualized, treated with outright hostility or clumsily used merely as a creative device, women have long been the butt of the joke, forced to the margins of the culture and vilified by practically every man to pick up a mic—from the founding fathers of the genre all the way to today’s biggest hitmakers.

That is what makes songs like “Hey Jane” all the more progressive and brilliantly well-considered. A track that explores an unexpected pregnancy from the perspectives of both the man and the woman, Tyler, The Creator has shocked me yet again—this time with his empathy and delicate thoughtfulness. On “Take Your Mask Off,” Tyler personifies four different people (including himself) who are hiding their truth, most strikingly personifying an unhappy housewife. Constantly reaching outside of himself, Tyler practically dares our patriarchal genre to grow up and try to meet him at his new-found level of mature lyricism that doesn’t exclude a woman’s experience from hip-hop culture’s narrative.

Chromakopia exemplifies the delicate balance that Tyler has achieved as a composer and a vocalist. His influences are barely obscured here: Kanye West’s widescreen ambition circa My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, the vulnerability of Kendrick Lamar’s Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, the Neptunes’ airy production work for Usher. You can even see the inspirations in his visual iconography—the album cover reminiscent of David Bowie’s “Heroes” and the sepia-tone militarism of the music videos a clear nod to Dr. Strangelove.

But for every glimmer of familiarity, there is something deliciously singular, such as the smash cut punch-in where Tyler nerdily interjects with “or those women” where one might expect to hear something harsher, or the delirious use of a Ngozi Family sample on “Noid” that gives way to a mood-shifting fusillade of keys. When he tackles the daddy issues that have been a recurring theme throughout his career on the stirring “Like Him,” it’s done as a ballad, not a banger. Tyler has learned that his bluster is more effective when employed sparingly, such as on the twisted funeral march “Thought I Was Dead” and the high-octane “Rah Tah Tah.”

Chromakopia is indeed yet another contemporary album that aligns with a therapy angle (we might soon be reaching maximum capacity industrywide for this particular brand of soul-bearing). But the more compelling theme of the album is about how our past trauma informs our present anxiety and what that looks like for Tyler specifically.

The surface-level way to read this is that Tyler is exploring his relationship with his parents and how their separation led to his trepidation around commitment and parenting. But this record can also be seen as an album-length mea culpa to those who haven’t let go of the Tyler who ate the roach. Tyler maturely explores the underlying reasons for his acting out over the years on Chromakopia, assessing why his urge for expression has often manifested itself in such an oppositional way. In an era when people are rarely given the opportunity to grow in the public eye and move on from their mistakes, Tyler’s growth presents an interesting question: What do we do with a maligned artist who actually does the work? With Chromakopia, we’re forced to examine the flexibility and finality of public image, to consider the possibility that there might be uncharted territory for those who do wrong that lies beyond social death.