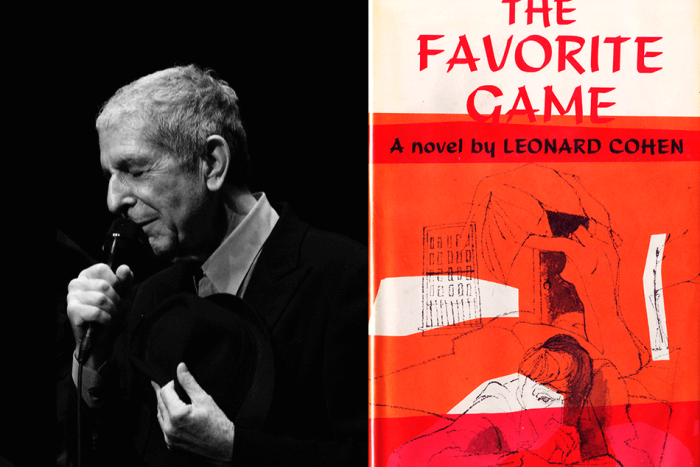

Like many of us, I’m fighting to stave off despair. As much I want to honor Leonard Cohen, who died this week at 82, I don’t want to listen to him right now because all I can hear is bleak, unremitting sadness. And this does a great disservice to a man whose art was never that simple.

On the surface, Leonard Cohen might seem like the ideal soundtrack for everyone in this country (and around the world) who is, in effect, in mourning. There were no depths Cohen’s lyrics wouldn’t fathom, no ideal he wouldn’t skewer or dismantle, no dark corner he was afraid to explore; he sang in a solemn, pained monotone that was as matter-of-fact as it was plaintive, and favored spare arrangements that seemed intent on wringing the life out of themselves; even on more orchestrated records, his use of empty space and choppy understatement were a constant undertow. He was never a companion or some kind of antidote; his art was a disavowal of the obvious, of any kind of reassurance. This isn’t going away. This is what we have to live with.

But if he refused to alleviate pain, he was anything but defeated. For over fifty years, Leonard Cohen proffered darkness without ever succumbing to it. He showed us how to live in it, forge it into language and handle it as an object; he taught us about flashes of levity, calm, ardor, or respite; and, while relief was seemingly out of the question, there was at least a way of making these emotions our own. It’s one thing to be consumed by doom and gloom; Cohen made them his palette, the hues in which he cast the human condition. They were his to manipulate and through this, we could begin to untangle what might have otherwise seemed like insurmountable emotional states.

And Cohen didn’t just pull this off for one brief, glorious song, or on a fully realized, consensus masterpiece of an album. This was his life’s work. Calling it the common theme across his discography is an understatement. In the same way that everything James Brown did was funky, Cohen’s music admitted sadness as a matter of course; even on more upbeat or satirical songs, he acknowledged its presence. There was no struggle—he let it in because to do anything else would’ve been fundamentally dishonest. The triumphalism many hear in “Hallelujah” masks desperation, longing and even futility; “So Long Marianne” is a full-throated paean, but to what? Loss? Fear of the future? The inevitability of regret? Our capacity to be ravaged by nostalgia? Cohen explored every way in which sadness seeps into our lives, especially when it came to love, sex, and any other need we have for direct human connection. He laid out every root cause and exposed every broke-ass dream that might spirit us away. There was no continuum, no sliding scale of happiness, just confusions that needed untangling. This was the human condition and it was rough. Here we are. And there may be nowhere to go.

What matters to me right now is what Leonard Cohen did with sadness in its most basic form. I badly need that sense of possibility. I need to feel that being crushed or demolished doesn’t have to be the end of the story but, rather, a stalwart beginning.

Cohen spared (and denied) us our self-indulgence. He demanded examination, even eloquence, around things we may have preferred to escape altogether. But if his worldview was one of hopelessness, it wasn’t cold, numb, or forbidding. If anything, it filled his music with life. I’m loath to invoke Cohen’s embrace of Buddhism—it lends itself to awfully facile analysis—but the acceptance that “all is suffering,” and the perspective that comes with it, and the freedom that comes with that, is key to his art. We may have no choice but to be miserable; there may be no situation or relationship that doesn’t, in some way, eventually boil down to sadness. But what Leonard Cohen did so brilliantly was show us how to navigate a broken landscape. He was so smart, so shrewd, that his observations were practically indisputable. But any hint of nihilism is fleeting; you’d never call Cohen a pessimist (he had too much faith) or some sort of crypto-optimist (there was no solution, only movement). He genuinely believed that all we could do was get by, and yet there was grandeur and opportunity in that. We could never escape or elude some simple, disheartening truths, but it was still possible to find your way; coping became creative, and getting by was an act of personal heroism.

Cohen wasn’t stricken, he was liberated; he wasn’t monolithic, he was prismatic. I’m sorry if it sounds like I’m selling short one of the most important and influential musicians of the last 100 years. What matters to me right now is what Leonard Cohen did with sadness in its most basic form. I badly need that sense of possibility. I need to feel that being crushed or demolished doesn’t have to be the end of the story but, rather, a stalwart beginning.

It says a lot about what’s happening with me—and, it seems, many of us—at this moment that Leonard Cohen is failing me. I know what he mastered and exactly why I need it now more than ever. I can describe it but I can’t tap into it. Listening isn’t the same as hearing; talking about feelings is different from experiencing them; observation is a long way from discovery. I owe it to Leonard Cohen, who has given me so much, to make it past sheer negativity. But I just can’t. And for this I am truly sorry.