The first time I played Amnesia, my character found a happy ending. There wasn’t much to it: he awoke, amnesiac, in a hotel room; stumbled to the hotel’s gym, passed out, had a disquieting flashback to time spent in a Texas prison; and eventually donned a tuxedo and made his way to a chapel, where a sinister man packing a gun made sure the wedding went off without a hitch. Stability, many children, and a farm in Australia followed, as did a peaceful death, haunted by the thought that something wasn’t quite right, that a mystery had gone unsolved.

Clearly, I had to play again.

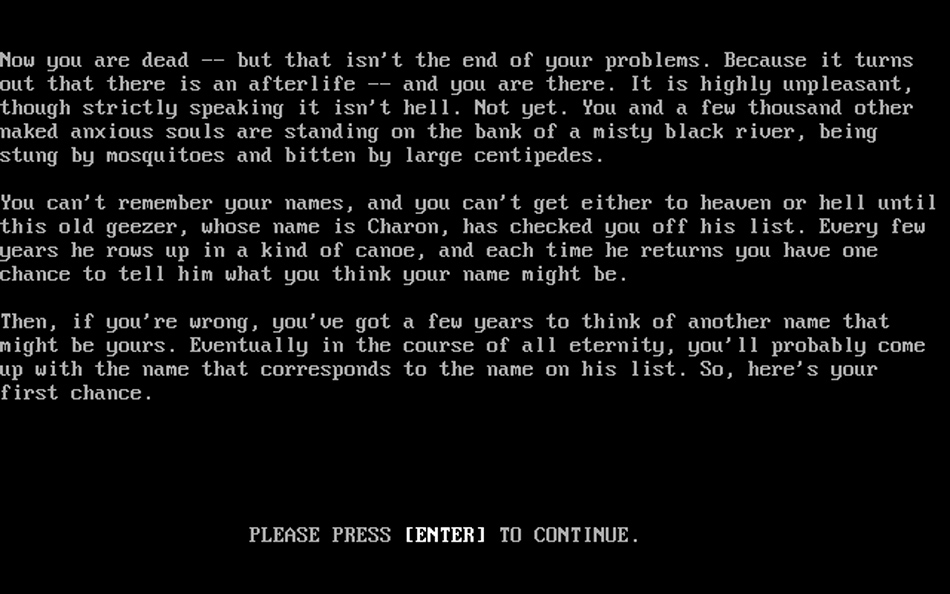

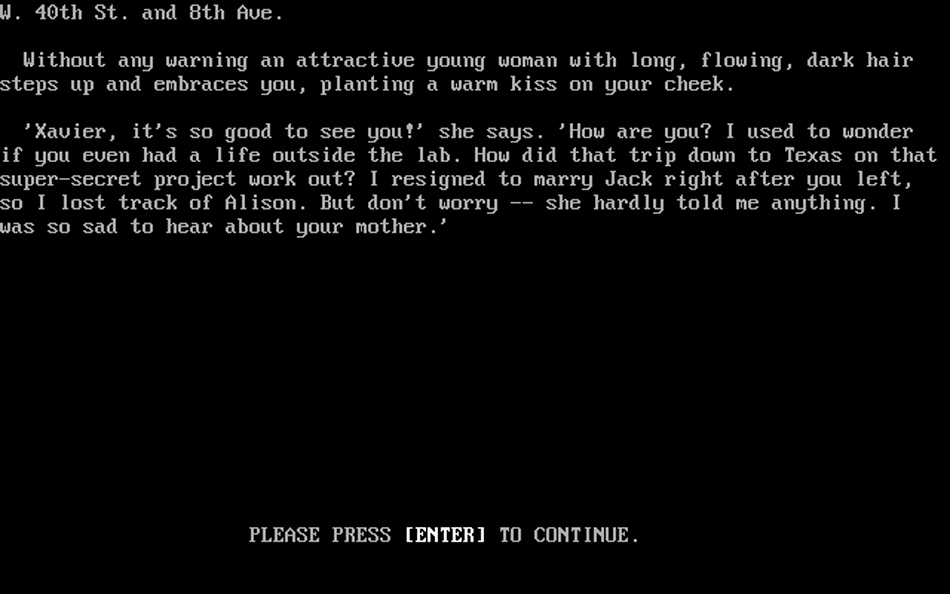

In my re-playings of the 1986 text-based computer adventure game that followed, my character was chased by the police; squatted in a tenement just south of Times Square; canvassed an abandoned storefront church; and quarreled with a celestial ferryman in the afterlife. He rode the subway, and wandered the streets of a surprisingly detailed Manhattan. He learned that he was named John Cameron III—or was it Xavier Hollings? As the game’s text appeared—sometimes witty, sometimes terrifying—I found myself hooked.

Amnesia was written by none other than the writer Thomas M. Disch, probably best-known for his science fiction, particularly the award-winning Camp Concentration. But his novels of the uncanny also extended to work in horror, including a thematically connected quartet of novels uprooting the seemingly upright archetypes within modern communities. I still have memories of one of them, The M.D.: A Horror Story, leaving me deeply unsettled on a family trip over twenty years ago. He also wrote the all-ages book The Brave Little Toaster, as well as its sequel, The Brave Little Toaster Goes to Mars.

Not many video games boast such acclaimed authors as their architects; the more I read about it, the more eager I was to play. I tracked down a copy, along with a document preserving essential facts from its ornate packaging, via the website Abandonia, and after spending time in its world, I found the experience captivating—both as a game, and in the way Disch’s unique literary sensibility made itself felt throughout. Amnesia blends a Hitchcockian wrong-man scenario with the setting of a paranoid thriller from the mid-’70s, spiking it all with a somewhat satirical take on New York City in the mid-1980s. Its central character must unravel the question of who, exactly, he is; how he came to be amnesiac; and whether he is, in fact, the murderer news accounts have made him out to be.

*

Disch’s work in both games and prose puts him in a relatively small peer group, though he isn’t the only one to cross over; recently, Tom Bissell made the move from writing about gaming (in, among other places, the book Extra Lives) to co-writing Gears of War: Judgment. These, however, are the exceptions rather than the rule.

Journalist Simon Parkin has written about video games for the likes of The Guardian, The New Yorker, Polygon, and the New Statesman. When I asked him about novelists who had tried their hand at game writing, he told me that “fewer novelists have attempted to do so than you might expect. Those that do tend to be writers who have a peculiar interest or prior familiarity with the medium, such as Alex Garland (Enslaved), Douglas Adams (Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) or Neil Gaiman (Wayward Manor).”

In Disch’s case, however, it may have been the way his writing affected readers that led him to gaming, rather than an inclination toward any form of writing in particular. His criticism, for example, contains some of his most gripping work—though that’s not necessarily intended as a compliment. The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World is what you might expect: a detailed history of how science fiction has gradually become part of mainstream culture. His 1994 collection, The Castle of Indolence: On Poetry, Poets, and Poetasters, was nominated for a National Book Critic Circle Award for Criticism. But reading Disch’s nonfiction can often be simultaneously enlightening and enervating: some of his writings fall into the unfortunate camp of liberal writers nonetheless bothered by aspects of multiculturalism; his discussion of Ursula K. Le Guin’s work in The Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of in particular is marred—to my mind, anyway—by his critique of her editing of The Norton Book of Science Fiction.

All of which is a long way of saying—and this is something of an understatement—that Disch can be a contentious figure. Go far enough into his body of work and there’s plenty to admire, but you’ll also likely find more than a little that will frustrate, or even enrage.

In the case of Amnesia, Parkin found that Disch’s aims as an author sometimes conflicted with the gameplay itself. “Even though the writing is strong in the game, you can see some of the inherent problems for any fiction writer working in a non-linear medium,” he wrote. “Disch limits the player’s freedom in many of the game’s scenes to ensure that the player progresses the narrative in the way he wants them to. For example, in the opening scene in which you wake up in a hotel room, you are not free to leave the room until the phone has rung and you’ve answered it. This curtailing of player freedom in favour of a set narrative path is regarded as poor design by some, even though it is arguably necessary for Disch to tell the story he wants to.” Compared to contemporary offerings, this approach can seem heavy-handed, especially in regards to the open-world approach found in the likes of Skyrim and the Fallout games, or the branching narratives visible in some of BioWare’s Mass Effect series. While a narrative that holds players in place until certain criteria have been met hasn’t gone away, some advances in technology have at least allowed it to be handled more elegantly.

Gabe Durham, publisher of the game-focused small press Boss Fight Books, found the self-awareness of Amnesia notable. “I think it’s more aware of what a text adventure is and why it can be fun,” he told me in an email. “At their worst, these games are like reading a map to a blind person: Go south. Go south again. Guess you can’t go south anymore. Turn around. You got eaten! Whereas this game takes the disorientation that is natural to the genre and makes the game about that disorientation. ‘Who am I? Why am I here?’ Well, let’s find out together.”

*

Amnesia disorients from the outset. As Hollings wakes, the player is asked certain questions about what you believe your character looks like: hair length, eye color, and so on. Disch’s script makes sure that, no matter how you answer these questions, your answers will be wrong:

“... when you look in the mirror, the stranger you see there has (long, short), (blond, black) hair. (He has a full beard. /or/ He has a mustache but no beard. /or/ He has, at most, a five o‘clock shadow.) And his eyes are emphatically (blue, brown). So far you‘re scoring zero on the Know Thyself Questionnaire.”

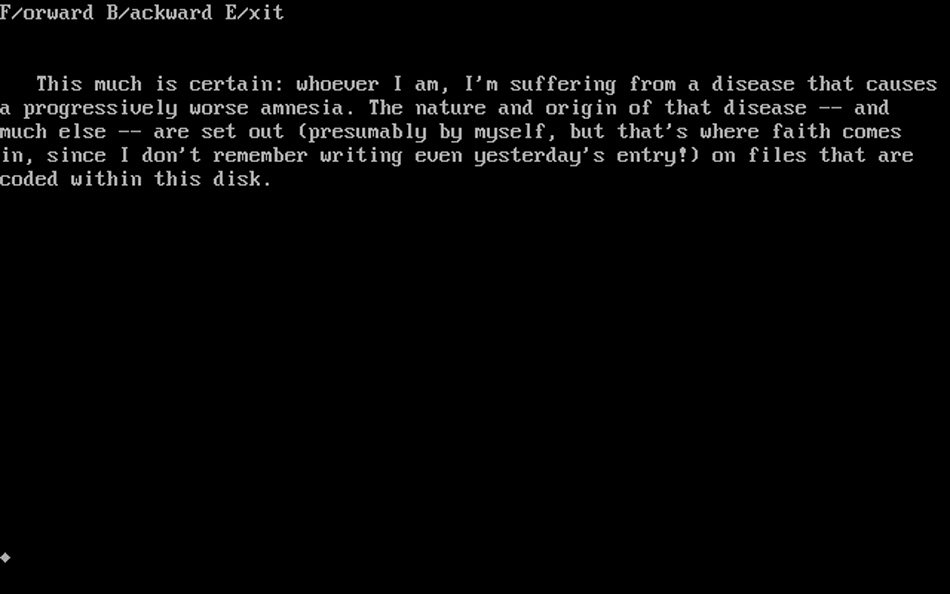

In the opening stages, Hollings will learn facts about himself through his interactions with assorted objects in his hotel room. His ease with a computer, for instance, indicates familiarity with that make and model. His reaction to pornography playing on the hotel television provides confirmation of his sexuality. Later in the game, Hollings will encounter a series of messages left by an earlier, less amnesiac, version of himself. They’ll be encrypted with a series of riddles; the earlier Hollings, in one message, notes that “[a]s for the riddles themselves, it seems that even in my amnesiac condition I have a knack for inventing doggerel riddles. God, I hope I don‘t end up discovering I‘m a poet!” (Readers familiar with Disch will note that, in fact, he was a poet—one of the little jabs of wit like that enliven the proceedings.)

What makes Amnesia particularly striking and gives it its replay value, though, is the way that information is parceled out. When Hollings discovers the encrypted messages he had left for himself, he discusses his apparent fiancee’s plan to farm in Australia as a likely con; play the game differently and you’ll discover that this, at least, is legitimate. Durham noted this as well. “Both times I played it to completion, it featured jump cuts where suddenly I am in jail,” he wrote. “What’s crazy is that in the second one, it turned out to be a dream, and in the first one I was for-real executed. So even when you actively search out new paths, you get echoes of these old paths.”

One of Amnesia’s most challenging aspects—or one of its most frustrating ones—is Hollings’s own stamina. Go too long without food or rest and he’ll find himself passing out; pass out and he’ll soon be arrested, tried, and convicted. But as he’s awaiting execution, Hollings will suddenly have an epiphany: a memory returns that could exonerate him, and which casts much of the ambiguity he’d previously encountered in a new light. This newfound knowledge did nothing to prevent Hollings’s execution from going forward. It was a devilish choice, as storytelling goes; it was also the sort of narrative moment that is most effective in the context of a video game. Perhaps most of all, though, it was a deeply literary choice—the kind of moment that could only come from a novelist working in a different type of media, helping push it towards new realms of possibility. For all that gaming today has expanded to include a wider variety of narratives, from ones where roaming a landscape is eminently rewarding to those where taking a step outside of a preordained path can end a game, Amnesia’s legacy points to a different sort of satisfaction: the kind that can come from a more controlled, authorial experience.