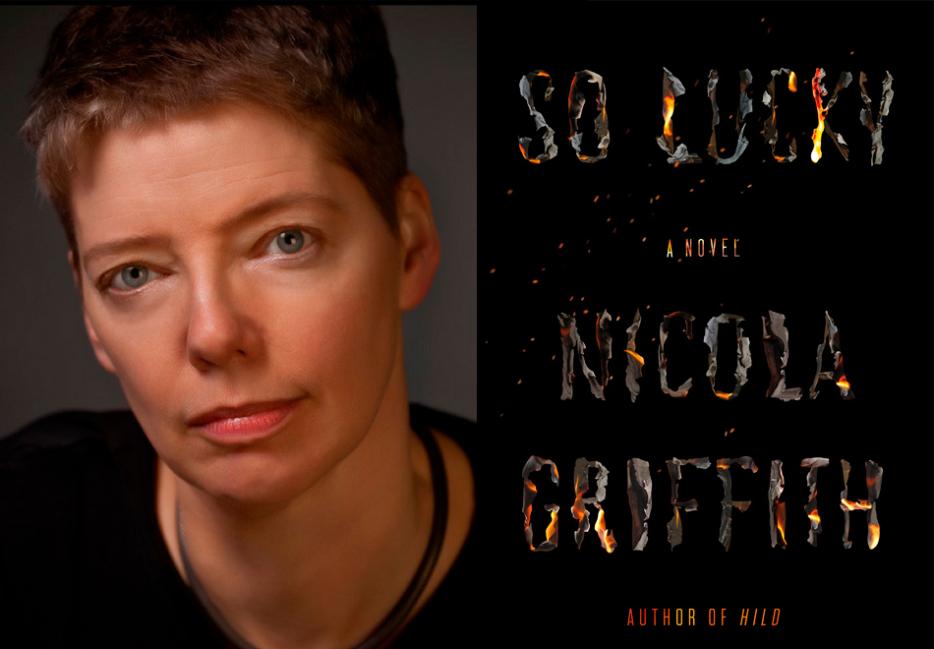

Nicola Griffith’s fiction abounds with detail, whether it takes place in seventh-century England (Hild), on a distant planet on which humanity has evolved (Ammonite), or within the complex social and economic dynamics of a near-future city (Slow River). Her books are powerfully immersive, and whether she’s bringing the reader into the distant past or the far future, there’s an almost tactile quality to their settings.

That aspect of her style takes on an entirely different context in her most recent novel, So Lucky (MCD x FSG Originals). Narrator Mara Tagarelli opens the novel at a moment of internal contradiction: while she’s the head of an influential public health nonprofit, her marriage has suddenly collapsed. She is diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, and Mara's evolving approach to dealing with this forms the bulk of the book. (Griffith has written extensively about her own life with MS, and about portrayals of disability in fiction.)

When Griffith and I spoke recently, we discussed the process of writing So Lucky, the novel’s relationship to the rest of Griffith’s bibliography, and how it relates to ongoing discussions about disability and accessibility in the literary world.

*

Tobias Carroll: In the afterword to the novel, you talk about the fact the writing of this book came as a surprise to you. Where were you in the midst of working on another project when this emerged?

Nicola Griffith: Well, I think of this as sort of misted avoidance behavior. I was about halfway through the sequel to Hild and I started to do a PhD. And then I got halfway through my PhD, and started to do this novel. And then, I finished the PhD, and now as soon as all this publicity stuff is done I'll be returning back to Menewood, the sequel to Hild. And I got a little stuck on Menewood, so I did a PhD. And I got a little stuck on my PhD, so I did a book and then I finished. So that's one way to look at it. And the other, of course, is that I actually wrote a version of this book a very long time ago. And I actually sold it. It was a novella and I sold it and I decided before it was published to pull it from publication, because there was something about it that made me unhappy. I wasn't pleased with it at all. Have you ever heard of the term narrative prosthesis?

I don't think so, no.

Okay, well it's a term used by two disability scholars, David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder.11Mitchell and Snyder also wrote a book on the subject, which was published in 2001. And it talks about how a lot of fiction about disabled characters uses disabled people, basically, as a metaphorical opportunity. Their narrative purpose, if you like, is the educational profit of a non-disabled character. And one of the things that one does in narrative prosthesis is that you eliminate the disability. Basically, you eliminate, the way people used to do in queer fiction. So, you know, death, suicide, leaving your lover so that she can be with a man in order to be more normal, that kind of thing. Or you fix them, which means being cured, having your problem overcome somehow. And disability is always the disabled person's problem in these books. Or you have an epiphany that makes everything magically feel better.

And I realized that what I had done in that original novella was, do this magical epiphany thing and then everything was better. I just realized that that was such bullshit and I couldn't stand it and I pulled it. But I didn't know how to write it, so I stuck it in a drawer and forgot it for a very, very long time. Until I was in the middle of my PhD and I suddenly realized that I now knew why I had been so uncomfortable with this story. Not just the narrative prosthesis, but because it was a kind of disability coming-out story and I've always had less than friendly feelings towards coming-out stories. I find them a little beginner-ish.

In So Lucky, you're writing from the perspective of a character who's going through a lot emotionally and physically, and is also an incredibly forceful character. What was it like to internalize that, to write from that perspective as opposed to something more detached?

It was interesting. Most of my novels are very relaxed and dense at the same time. And they're large. But this felt much more like a spear thrust than normal. I had a very specific thing I wanted to address. It wasn't all about how systems work or what it means. It was about how this particular moment feels. In that sense, it's much more like a short story than a novel. It's a moment, it's a sort of extended downplay moment, but it is a moment, as opposed to a distant look at something.

A lot of my novels, they're very much centered in the body, and how we learn about the world through our body. But there's also, as you say it, a certain distance from what that means, a certain analytical stance. And I did not have an analytical stance writing this novel, at all. It just came pouring out, like this torrent. I wrote the first draft in two weeks.

It was this raging current, and I had two and a half weeks. I sent in the first draft of my thesis to my advisor. And then I was like, well what am I gonna do for two and a half weeks? Oh, goddamn, I'm gonna write that story I've been meaning to write. And it just came roaring out.

Did you find that your process for writing this differed from, say, writing Hild or writing one of your earlier novels?

Oh, sure. I didn't do any research at all. I did a little bit of research afterwards, but really not much. This is the least researched thing I've ever written. I researched even my short stories more than this. This was very much, I had a thing I wanted to say and so I just sat down and said it. And then afterwards when I was rewriting, I would think, okay, I need to know a little bit more about that and I would go find out something. But now, it was a totally different process. I knew what the ending image was. And I knew how it started. But the rest was kind of a mystery to me.

I also knew that there was this scary part with, basically, people hunting down disabled people. Because that was actually a moment from my own life in the ’90s. I was cooking something and CNN was on in the background and I heard about this torture case, and I was super shocked. So yeah, on some level that actually happened. I don't know the person's name or where they were or anything. But the fact of the facts, someone with MS was essentially tortured and killed in their own home... That's real, yeah.

Oh, god.

Yeah, it really woke me up, I can tell you. It made me realize for the first time how it would feel to be a victim. I'd never felt like a victim before, but that moment just made me think, oh my god, yeah, I'm the kind of person that people would maybe think [of] in terms of victimization now.

You're writing about a character who is very angry about certain things in society, where you may share that anger. But in the novel, there's also this sense that Mara is perhaps using anger as a sort of a defense mechanism and as a coping mechanism. How do you balance that sense of outrage with having this particular character's outrage as a dramatic element?

I knew when I sat down to write this that everyone would say, oh my god, it's autobiography. And of course, I know it's not, but I very much used elements of my own experience in there. But I tried to think, okay, how can I make this about a person that I would understand but that who is not like me? And so I chose this kind of brittle, defensive anger, because that's not how I approach the world.

I can get angry, but it's very fast and it's not a stance to the world. It's usually, something happens that really pisses me off, I get pissed off and then I forget about it. But Mara is much more brittle. She feels a little less secure than most of the characters I’ve ever written. Most of the characters I write come from a place of quite high self-esteem. And Mara, on the surface, has that, but I think there's something a little more fragile underneath that.

In So Lucky, you're returning to Atlanta as a setting, which you'd previously used in The Blue Place. What was it like returning to a city that you had used as the central point of one of your previous books, in a very different context?

This is another way in which this book is really different. It could be set almost anywhere. There is nothing very particular about it. There's mentions of neighborhoods, there's Lake Lanier. But really, it could be pretty much anywhere. It certainly could be in, say, North Carolina or somewhere like that. Somewhere that's about the same kind of temperature. It's very non-specific. It didn't really matter to me. So in that sense it was kind of an easy thing. This is where I was first living when I was first diagnosed, so it just seemed like the default setting. It wasn't a conscious choice at all.

When the book was finished and when I was talking to my editor about it, he said, "So why Atlanta? Why not Seattle?" I said, "I don’t know, just seemed like a good idea at the time." Also, because the very first time I thought about this story, when I wrote it twenty years ago, I was having thoughts and making notes for the draft, at the same time I was actually writing The Blue Place.

So there's a mix there. And if you actually read the book carefully—I don't bother doing a lot of description—Mara’s house is actually Aud's house.22Aud Torvingen, protagonist of three of Griffith’s novels: The Blue Place, Stay, and Always. I realized as she was moving through the rooms—I thought, damn, this is the same house. So there is some weirdness in that way, but because I never felt as though it was particularly important, I just thought, why change it? It's fine.

So much of what Mara goes through is in terms of the way the temperature of a specific place can affect her. Having the book be set in somewhere where it is going to be fairly warm and fairly humid often added to that.

That was very useful to me. Because here in Seattle, what happens is that it only gets hot at certain times of the year and nobody in Seattle has air conditioning. Because they're all like, oh, it doesn't get hot in Seattle. Except every year it does, but just for a little while. The people here are ... well, they're kinda cheap. It's like, well I know we can just hang in there for two or three weeks. And me, I'm like, oh no, I want air conditioning. Even if it's just for two or three weeks.

I saw on your website that you recently got the rights back to the Aud books?

Yes, I am so excited about that. It was always meant to be five books and I just stopped writing them. Partly because of the MS thing, but honestly more because of the publication issues. But now I'm back on track with being okay with all the MS stuff, and I've got the rights back. Oh, I'm so looking forward to it. You know what I'm really excited about the Aud books is the possibility of doing the audio narration.

I did the audio for So Lucky, and I enjoyed it enormously. So I really want to do all my books now. I'll just have to go back to my entire back list and turn them into audiobooks.

Where in the stage of writing this book did the title come into play?

Fairly late. It was originally in my head, it was called Season of Change. When we first meet the old woman and she has the little dog, except it may not actually exist, I started thinking of it as Small Dog Theory. There's a small dog theory of illness: you treat it like this little yappy thing over there, keep it well fed and it won't bother you so much. And then I realized that that theory was bullshit, so I didn't want to use that. And then I hit this exchange between Mara and Rose about, “Oh well, fuck you, you should be so lucky.” And I thought, huh, I think So Lucky is rich with irony, not irony, and all the different layers of that. So I chose that.

It's one of those things that resonates in different ways depending on where you are in the novel, which I really appreciated.

Yeah. No, I like the title. A couple of people were like, can we do something else? I'm like, nope, that's the title. Take it or leave it.

You have a book coming out about a character living with MS, and I feel like in recent years questions of accessibility in literary spaces are more and more coming out into the open. I feel like every year there's a lot of discussion about the AWP Conference not being particularly great in terms of accessibility.

Oh, god, yeah.

Is the hope that this book will also enter in that debate, in addition to being a work that stands on its own?

Well, sure. I always like my books to actually have an effect in the world. I write because I want to find out, and I write because I want to change the world. And this book helped me figure out some things, pretty much at the same time as I was figuring out other things in my PhD.

And then I'm hoping that it really helps people to see that, just because you're disabled doesn't mean you're a pitiable creature. You know, you have a life. It's just that you might use a wheelchair instead of your feet. Or you might use a support animal instead of your friend. People just have different ways of approaching the world, and I just want, honestly, readers to see disabled people as human beings in and of themselves.

It goes back to this whole notion of narrative prosthesis. Most people's notion of disability is super sad, heart-wrenching and all inspirational things that they see on TV or read in books written by non-disabled people who haven't a clue. The kind of things where you see someone in a wheelchair and they are confined to a wheelchair. They are bound to a wheelchair. Or other people look at them and think, oh, if I was in a wheelchair I'd just kill myself. And that's how we learn ableism, is from all the stories out there.

So, this is my version of just writing a story I want to write, but also a way to sort of overwrite the ableist narrative. Just give people a different story to replace the old story.

Have you found that your PhD work has affected your work in fiction as well?

One of my worries when I was working on it was that, yes, it would change my fiction. And in one sense, it already really has. I couldn't have written So Lucky without doing that PhD.33Griffith’s thesis, Norming the Other: Narrative Empathy Via Focalised Heterotopia, can be downloaded from her website. I came up with a portmanteau term, focalized heterotopia. This one's focalized heterotopia, in the sense that the focalized character, Mara, is queer. And queerness isn't the point, it just is. And she doesn't run into any homophobia or sexist violence because of being a woman or being queer.

But I realized that in the disability sense, what was making me so uncomfortable about thinking about writing So Lucky was that I would be making a person's difference one of the points of the story. And I have never written about lesbianism or about being a woman. And here I was, writing on some level, about disability. Except, of course, then I realized that really it's not about the person's problem with disability. It's about the world's problem with her disability. It's about how life is much more difficult in the world because of being disabled. So, doing the PhD really helped me write this book—in that sense, yes, it's totally changed things.

In other ways, I'm hoping not. We'll know when I get back to Menewood.

Whereabouts are you in that right now?

I'm about 90,000 words in and it's going to be another long book like Hild, so probably I'm about forty percent there.