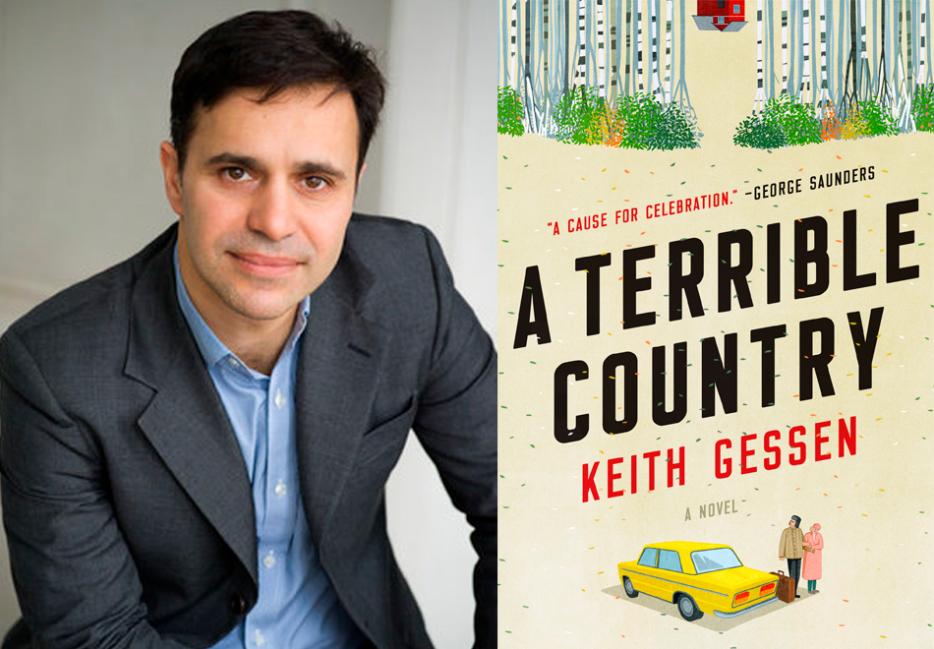

Keith Gessen's second novel, A Terrible Country (Viking), is a moving story about a young man taking care of his ailing grandmother in a changing Moscow. Keith Gessen’s second novel, A Terrible Country, is also a subtly terrifying story about the rise of authoritarian politics in contemporary Russia. That this novel can contain both of these aspects is no small accomplishment; in telling the tale of Andrei, a young academic who returns to Moscow from the United States in 2008 for familial reasons and falls in with a group of passionate leftists, Gessen has crafted a story that resonates with the present moment in numerous ways.

As Andrei muses on Russian literature, the role of capitalism in post-Soviet Russia, and his own fraught connections to his brother and grandmother, Gessen is able to weave in narrative strands both sentimental and cerebral. It’s a work that reads like the accumulation of his own areas of expertise: he’s a founder of the magazine n+1, he’s translated several literary works from Russian into English, and his writing includes everything from fiction to analysis of global politics. We talked with Gessen about the genesis of A Terrible Country, the unruly relationship between hockey and fiction, and the tricky business of writing literature about Russian literature.

*

Tobias Carroll: I wanted to begin in a place that’s hopefully related to A Terrible Country: you recently had a piece in the New York Times Magazine about “Russia hands” and the way that perceptions of Russia have affected American foreign policy. I was wondering how much of an overlap there was for you in terms of working on that piece and going into some of the history and philosophy of this novel?

Keith Gessen: I wrote the piece when I was done with the novel, but I guess they come from the same kind of place, of thinking about Russia in a more complicated way. The book probably comes out of a certain amount of frustration with what I was able to accomplish as a journalist with regard to Russia, in terms of communicating how complicated and rich and contradictory actual Russia is. It’s something that I feel like I failed to communicate as a journalist. So I've tried, in this novel, to to do that. In that way, the novel is a more congenial form for communicating some of those things.

At what point did that kind of frustration lead into the book? Had you already had some notion of it and then the thematic overlap became apparent, or was that kind of the initial impulse that the novel grew out of?

Yeah. You know, I was born in Russia and I have been back and forth a fair amount since the mid nineties. So I was going there a lot; sometimes I went there less, and I spent a year there in 2008/2009. While I was there I thought, "Well I couldn't possibly write a novel about this place, I have family here and I was born here but I just don't really know enough about the people here. I know enough to do journalism, which is where you have to get your facts right, but you can just follow the facts. Whereas with fiction you need to know a place well enough to make stuff up.”

At least for the kind of fiction writer that I am, I need to know a place really well. I don't feel confident making stuff up unless I really know all the possibilities of how things could go. I feel like you need to know a place really well to be able to do that. When I was over there I mostly concentrated on doing journalism, and then I got back and that time started to seem like a story with a kind of beginning/end that I could write about. It's mostly a story about this guy and his grandmother, but that would in the process sort of touch on a lot of things about Russia and the contemporary society.

I thought that was something that I could manage. Initially I had this notion that I would put everything that I knew about Russia into it, so I had this draft where I spent a year at the library, the New York Public Library. I had the Cullman Center Fellowship, where you go there every day, it's part of the deal. You have to go there every day and they can order any book that's in the library system, including books that are in the storage in New Jersey. They arrive by the next morning. You just sit there on your computer with any book you can think of and then it arrives.

So I was just sitting there ordering books all year and reading them and stuffing the narrative full of histories of Russian literature and Russian oil and Russian politics. At the end of the year I had this draft that was incredibly long and consisting, at least in half of it, of these long essays. I sat down and read it, and it was just totally impossible to read.

Oh no.

That was a discouraging moment. It wasn't the darkest moment in the composition of the book but it was up there. I was like, "Ah, okay. That's not gonna work. I need to try to communicate stuff about Russia but in the form of a story." It's just a matter of, at that point, deleting stuff and seeing what remained of the story at hand. In fact, making the story more about the grandmother, actually.

Since you mentioned it, what was the darkest moment in the writing of it?

Probably the darkest moment was when I was six or seven years into it and I had spent a day working on a scene and then toward evening I was tired and started cleaning up my apartment, which is not something I do very often. But I did some cleaning up and was putting some notebooks away. I was putting one of my notebooks away, and I looked into it. It was a notebook where I had been writing the book three or four years earlier, and I found the exact same scene, basically written in the exact same way. At that point I realized I was rewriting the book again, and that was a dark moment. Another dark moment was when the book was further along, and I kind of went through it and I thought, "Oh, I have a pretty reasonable draft here, I just need to go in and explain some stuff."

I spent this period of time where I went to my dad's house; he sort of lets me live in the basement. There's a Starbucks, and I’d go and sit there for ten hours. I just filled in all this background of the characters and I sent that off to my editor and my best reading friend, and they were both like, "It's a little long."

My friend Chad and I had this argument about how long it was. When you're working with these Word files, you don't actually know how many pages it is, and Chad went and read it and said, "It feels it's about 600 pages, it must be, what, like 600 pages?" And I was like, "No, no, it's 300 pages!" And in truth it was something like 450 pages, meaning I thought it was shorter than it actually was, and Chad thought it felt even longer. That was another dark moment. From there again it was just a matter of cutting stuff out, and it turned out I didn't need all that stuff.

Because you set the book when you did, I felt like I learned a lot about Russia at that particular moment in time, but it seems like there are also a lot of parallels to the American political situation in the last ten years: the rise of a strongman leader, union-busting at universities, and the efforts of people to make a better life here. Were those parallels conscious, or was it something that emerged as history played out?

That was history. The interesting thing about Russia is that, I think we think these historical processes are very different, and that what’s been happening in Russia was, until recently, very separate and discrete. But as the real-life Russian left has been saying for awhile, what you see in Russia is actually a form of capitalism. In certain ways it's behind or less advanced than what we have in the U.S., and in other ways it anticipated a lot of what we're seeing here. Those descriptions of fights over privatization of universities, those arguments in Russia were happening before they started happening here. Probably because they had public free education under the Soviet Union and then it started getting privatized, and we didn't really have that, and in Russia they started being privatized in the nineties. In the U.S. that really started happening to the state universities after the financial crisis. So they were ahead of us in certain other ways, also in terms of union busting. I've always found that being in Russia is very clarifying for my understanding of the American political situation, because things are more on the surface.

In the U.S. things are just more complicated; there's a kind of corruption. In Russia it's really in your face. Pretty much every time I've spent a lot of time in Russia I've come back and been able to understand things that are happening here a lot better.

You brought up the Russian left in the real world, and you definitely have a component of that in the novel, so I'm curious about where for you the line is between wanting to faithfully represent the arguments of the Russian left but also incorporate it into the novel in a way that is a functional part of the story you're telling.

You don't want to these long lectures in your book, but ultimately the kind of content—if you're like, "Okay, I'm gonna go ahead and have some lectures, I'm just gonna do it"—this book is going to be one of those books that has a few. [And] as I suggested earlier, there used to be a lot more than that. It's down to the bare minimum that I could live with. I needed some of that. If you're going to have lectures in your book even if you cut it down to the bone, as far as fiction it doesn't really matter what the content is in terms of their function, whether or not they work in the novel.

The question is, can you connect them to the rest of the novel? And also, do you think they're true? I happen to agree with Russia’s left and the things they say in here that I have that I think are true. The trick for me writing it… when you're writing about people you actually admire, it's harder in a way. It kind of depends on the kind of writer you are, but I find it easier… when I'm reviewing books I always found it more fun to write critically and I find [that] easier than to write appreciatively.

In fiction I'm the same way. I find it pretty easy to make fun of characters and a lot more difficult to write an interesting viewing character. One challenge was just not making them into paragon of virtue who were perfect people who were totally right about everything. Make them sort of human, but some humans are more right than others. Some people live more ethically, or try to. I really like these people, I was just trying to make it not too gushy.

The other challenge is trying to make the stuff they say and think relevant to the reader of the book. I don't know if it's effective, I don't know if it works, but ultimately what I figured out at some point—it was staring me in the face the whole time, but it took a while to get there—is the grammar of the story in a way is this great argument, at least against capitalism. Andrei realizes that at a certain point and I as the author also realized that. I hope it's more organic to the book. It makes more sense to the grammar of the story.

I really liked the speech Sergei gives in the book store, and I liked the fact that he also has ties to this completely other different part of the novel, which is to say all the scenes of Andrei playing hockey. This is one of the handful of novels that I've read that delves into the world of playing ice hockey. Why do you think there have not been a ton of books about hockey? I can think of baseball novels and football novels and soccer novels, but other than the one Don DeLillo wrote under a pseudonym, I can think of very few hockey narratives.

It's very sad! It's a great tragedy of our literature.

Seriously, I think maybe for the same reason that there hasn't been a lot of lacrosse novels. Hockey in a way is a Canadian game. It doesn't match the way or obviously speak to [us] about American themes of race or class in the way that basketball does and the way that football does, the way that baseball does. I can't think of a ton of football novels either. I love hockey, and that's the sport that I played growing up and in Russia it is a natural, less of a stretch, I think in the context.

I kept thinking I was going to have to cut it out—it was a real treat for me to write about hockey. But I thought, "Well, the day of reckoning will come when I read this novel and see I have to cut out all the hockey." And there used to be more hockey in it, but ultimately it turned out to be a kind of fun thing to have in there, not necessarily extraneous, and part of the fabric of Russian life in a nice way. I was very happy to be able to do that for hockey and American literature.

In a case like this when you're writing a novel about someone whose area of study is literature and you're throwing in a couple of references to the stories and novels they're teaching, how do you balance that so it feels organic? In terms of the Chekhov works or other things you alluded to, would you say there were parallels if one was to work closer and do some reading based on the books cited in this, would they find some sort of resonant moments within your novel?

I think so. I think it's always tricky having explicit references to literature inside of literary works. As a younger reader, I always found them pretty off-putting, because I hadn't read a lot of these books. My reaction was, "Do the work of whatever you're trying to say, explain it to me. Don't send me off somewhere to read another book, I'm reading your book." I feel like the guy is a literature adjunct professor so it's a big part of his life. It was a big part of his grandmother's life—he is surrounded by other people who study this stuff. In a way, to exclude this stuff would be almost unrealistic.

It's certainly true, when writers and literary people get together, that they talk about TV more than they talk about books, but they do, in the end, guiltily discuss some books here and there. It seemed okay. Within that, there used to be a lot more of that stuff and now it's down to Tolstoy, Tsvetaeva, Shmelyov, maybe a couple of others—Chekhov, he keeps reading Chekhov's story.

I had to choose wisely. I hope it's presented in a way that you can give a capsule summary. The first-person narration, I found it really tough going a lot of the time, it's pretty confining. It's a pretty tough point of view, it was for me, working in the first person. But one thing first-person is pretty good for is a broad summary. It is a pretty natural thing when you're talking to someone about some work of literature or film that they haven't encountered that you give them a summary of the plot. That's something that happens in conversation a lot. You have a kind of conversational narrator, it's not crazy for him to do that. I feel like most of this stuff is described in the book, it's not just allusions.

Certainly The Cossacks is one book that's alluded to in the text that served as a model in terms of the basic story line of the book for me. That's a book where—it's an early Tolstoy novel, very understated in terms of what happens in it—a guy goes to a Cossack village, finds it difficult at first, and really falls in love with it, doesn't want to leave, and then he has to. That's always been one of my favorite things by Tolstoy, and in a kind of very general outline that's what happens in this book, too.

I know you've also translated a couple of books. Would you say there are writers writing in Russian or places translating Russian writers into English, either fiction or nonfiction, who, if someone enjoyed your handling of the Russian left and the current political situation, might be a good next step for them to go to?

Certainly. A writer I've translated and really admire is a guy named Kirill Medvedev. With a number of other translators, I did a book called It's No Good, which is a mixture of his poetry and essays about contemporary Russia, and about what the 1990s looked like in Russia, and his search for political and personal position on all of that. I would definitely recommend that.