We have a morbid obsession with watching people willingly suffer in remote locations. Wilderness survival reality TV shows like Naked and Afraid, Dual Survival, Survivorman and the original, Survivor, offer viewers a voyeuristic glance into the remarkable and grotesque acts humans will commit in order to survive. Make bikinis out of palm leaves. Drink their husband’s urine. Feast on roasted rats. Spoon naked with a stranger for warmth.

This obsession transcends reality TV shows. We devour news stories about hiking trips gone awry, where campers survive on mushrooms and muddy water for weeks, and non-fiction works like Into the Wild, which prompt a range of internal questions of self-sufficiency like “Could I build a shelter out of leaves and sticks?” and “Could I also kill a moose and eat it?” From our cushy sofas in our comfortable homes, it’s fascinating to witness humans push themselves to their most extreme limits and imagine ourselves in their situation.

But once the episode ends or the article is over, and we’ve consumed all the gritty details, we rarely hear about what happens to these people. There are rarely follow-up pieces about how they cope in the weeks, months and years that follow.

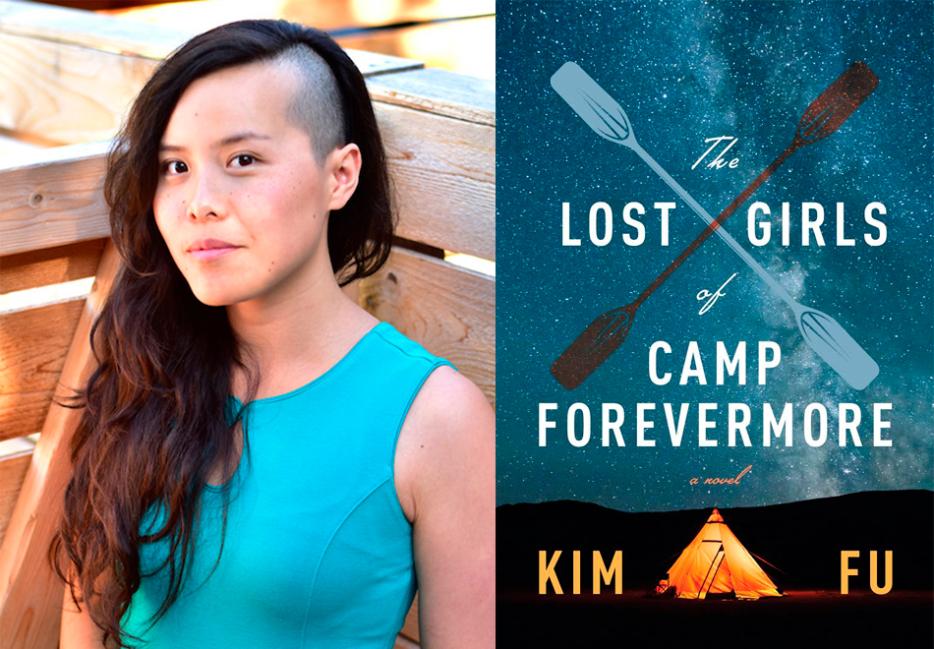

In her new book, The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore (HarperCollins Canada), Seattle-based writer Kim Fu examines the aftermath of one of these survival stories. The book follows the lives of five girls—Nita, Andee, Isabel, Dina and Siobhan—who meet as pre-teens at a summer camp in the Pacific Northwest. After a tragedy strikes during an overnight kayaking trip, the girls are forced to fend for themselves. Unlike Naked and Afraid, Survivorman, et al., The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore focuses less on the gratuitous details of the girls’ survival (although there are some wonderful scenes of them rationing their small reserves of trail mix and peanut butter sandwiches). Rather, the heart of the book focuses on the various ways this traumatic experience affects each of the girls in the decades to come, as they mature into teens and adults. It’s an engrossing portrayal of how trauma can affect lives in countless subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore is the follow-up to Fu’s debut novel, For Today I am a Boy, the story of Peter Huang, a Chinese-Canadian woman trapped in a man’s body, which won the Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. In 2016, Fu published her first poetry collection, How Festive the Ambulance. I called Fu to chat about summer camps, growing up adjacent to Vancouver and the expectation of Asian authors to write Asian characters.

Samantha Edwards: Did you go to summer camp growing up?

Kim Fu: Not the kind of all-girls sleep-away camp in the book. I went to a public school in a suburb of Vancouver that had something called “outdoor school,” which is kind of a similar format. As children, we went on these overnights that involved ocean kayaking and outdoor rock climbing, and at one point there was even a zip line. Looking back, it seems really physically demanding and dangerous and strange that we were doing this as ten-year-olds.

What suburb did you grow up in?

I grew up on the North Shore, so technically its own municipality but functionally a suburb.

I grew up in Ontario, just north of Toronto. At my high school, we had an outdoorsy class where you learn…I actually don’t really know what you learned, now that I think about it. I just know they went camping. But that was a grade twelve class. It wasn’t for young people.

That’s what makes it so weird to me. The first time I tried to go ocean kayaking as an adult, I thought we could just rent kayaks and they were like no no, you have to take classes, you have to get certified, you can’t just take a kayak out in the open ocean. And I was like, really? When I was a kid, they just put a bunch of us on kayaks and put us out in the ocean.

Were you an outdoorsy person as a kid?

I would have said no, I was very much not an outdoorsy kid. I was an indoor, book-reading, video game-loving kid. But then I think some of that is a matter of perspective. Where I grew up, in my head it’s a suburb, but it was actually up on a mountain. I saw bears fairly often. Bears would just go through the backyard, or you’d see one on the way to school. That seemed totally normal to me: the nearness and availability of the outdoors, that you could walk a few minutes from your house and be completely enveloped in the woods, the lakes and the mountains.

When did you start thinking about the idea behind The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore?

The characters actually came to me first, but I didn’t know what kind of context they were going to be in. With both of my books, the characters came to me first. With For Today I am a Boy, it was a lot easier to know where to go from there because they were a family, the dynamics around them could dictate the plot. But with The Lost Girls, it’s like I had these five women in mind, and I didn’t really know how they knew each other. I tried lots of different things, maybe they lived on the same street, maybe they just went to school together. I wrote these scenes where they were interacting with each other but nothing was quite right.

I was picking at these people for like four years almost and then in 2015, I did a writing residency at the Berton House in Dawson City, in the Yukon. I was there in the winter, during the freeze up. I had all this time to be out walking in the woods. I was thinking a lot about outdoors survival, all these skills I don’t have and my own physical vulnerability. This image came to me of these women as little girls in kayaks and the book cracked open.

I read in an interview you did in 2015 while you were doing press for For Today I am a Boy, where you mentioned that at one point, it was easier for you to write from the perspective of men or women with stereotypically male interests. This book is written from the perspective of five women. Was that was challenging for you?

[laughs] I have no memory saying that. I had such a hard time promoting my first book. I feel like I didn’t get to enjoy so many wonderful things that happened because it was this constant state of anxiety for me. I feel like I don’t remember any of the things I said during that year and a half.

I don’t feel like I have an easier time writing characters who are more traditionally masculine. I feel like now, and definitely while I was writing The Lost Girls, I’m much more interested in women and women’s perspectives and experiences of the world. A few people have brought up that all the male characters in The Lost Girls are secondary, they exist only in connection to the central female characters. People ask if that was intentional. I did notice that while I was writing and I decided I preferred it that way, because so many books exist already where the reverse was true. I hope that all the men in my books are presented as whole human beings, but I was aware that they’re more of a background element. It’s these women who are moving through the foreground and who are important.

Do you mostly read books with non-male protagonists? Are you drawn to those kind of books?

I read everything all over the place. In the last couple of years, I’ve made an effort to read more books by women, but in terms of the gender protagonists, that’s tricky. I wouldn’t say I’m drawn to one more than the other.

Recently, at my book club, we were talking about whether or not we could sense that a man was writing a female character in a particular book.

I still think men who write woman characters well are rare enough to be notable. I’ve read some books, and I don’t want to name them, that were really excellent other than this one thing. They would be books that were centered around men, but when the woman character appeared, the way she’d be written would just pull me out of the book. It was clearly a flaw, not just on the part of the writer, but it was clear that no woman was involved in this book. That everyone involved in this book must have been a man. In the obvious ways, the way her body is sexualized or her own thinking about herself is sexualized. In the abstract way, where the women exist to nag at men’s ability to have passion for things that aren’t human relationships. And also in little details, like a woman paints her nails on the way out the door. It’s like, you can’t do that. A woman copyeditor would have picked that out. That’s not how painting your nails works.

You’re not going to paint your nails and then jump in the shower.

Yeah, exactly. Little things like that would eat away at me and sort of ruin the experience of an otherwise good book.

Can you think of any books where a man has written a female character really well?

The one I always think of first is Gloria by Keith Maillard. Disclosure: He was a mentor of mine at one point. Gloria is a period piece about a specific kind of sorority girl in the 1950s. I feel like it captured really well how much brain power women have to waste on negotiating people’s expectations around their appearance and managing other people’s emotions. To me it was this amazing exploration of femininity that was written by a man.

Another one is The Fortunes by Peter Ho Davies. The book has four sections and one of them is about Anna May Wong. Even though it’s about a particular historical celebrity, I think the book [offers] a really good depiction of the experience of moving through the world as a Chinese-American woman.

I was actually reading the piece you wrote in 2016 for Hazlitt that’s partially about The Fortunes and also how you realized in your early twenties that you “failed at whiteness and Asianness.” I related to that piece so much. People always ask me “Where are you from,” and I know they don’t want to hear how I’m from Barrie, Ontario. They want to know why I look the way I do. So when they find out I’m half-Japanese, one of the first questions they ask is if I speak Japanese, and I don’t. I realize that even if I don’t speak the language that it shouldn’t somehow disqualify myself from my own identity and culture, but it always felt like this embarrassing thing for me to admit.

For me there were two big turning points. I grew up adjacent to Vancouver, where it was quite racially diverse and there was a high percentage of Asian people my own age. I did my undergrad at McGill, so when I moved to Montreal, it was kind of a shock. It wasn’t the first time I had encountered casual and inexplicit racism, but it was on a different level in Montreal. Just walking around the street and the things people would say to you and the conversations they’d strike up at the laundromat. Honestly at that point, [my race] was a background part of my identity. It didn’t seem as salient to me as it did to all these strangers in Montreal.

The other thing that happened was my father passed away. In the course of his illness and then death, I realized I knew so little about his life and his parents. I think because other people saw me as Chinese, [I had] that feeling of disappointing people or being inauthentic. The first thing they see you as is Asian, but then you’re not Asian enough. There was this period of time where I was trying to learn, I was reading tons of books and watching movies, and learning to cook, I was trying to get in touch with this heritage like it was going to explain something to me. And sometimes it did, but in this very distant and abstracted kind of way. I read Five Star Billionaire by Tash Aw and I felt like the way depression was depicted in that book spoke to experiences I’ve had with depression more than say The Bell Jar, and that didn’t feel coincidental. That felt like a cultural thing.

In The Lost Girls, I really enjoyed the characters of Isabel and Dina, the two Chinese-American girls. In the book, you mention Isabel’s Chinese last name in the first few pages, but when I got to her section, I completely stopped thinking about her race. It was only when she was told by a stranger that she looked like a Malaysian pop star that I realized, “Oh right!” I liked that because sometimes I feel like that’s the major identifier when there’s an Asian character in a movie or book—them being Asian is their whole bit.

A writer recently posted on Twitter that he had his manuscript rejected because his Korean-American character didn’t spend enough time thinking about being Korean. And it’s like, that’s not what you do. You don’t look in the mirror and mentally remark on your Asianness all the time.

But then when I read Dina’s section, her Asian identity is a big part of her. There’s that line when she’s struggling with an eating disorder and someone says, “Oh, you’re so lucky you have that Asian metabolism.”

She’s very beautiful, so from a young age that affects how people talk to her. There’s a line where when they’re young teenagers, one of her white friends says “You’re so lucky, Asian girls can be so weird looking but you look totally normal.” Someone has said that to me! As a kid, you know what they mean. They mean certain aspects of your appearance lean white, so aren’t you lucky that you have some white features. As a kid, you absorb that kind of thing, “Oh right, looking more white is a good thing, that’s what being attractive is.” For Dina, with her whole life wrapped up in her appearance, of course race is going to be more salient for her. I feel like I’m using the word “salient” a lot.

When I interviewed Celeste Ng, we chatted about the expectations of Asian authors to write Asian characters. What do you think of that kind of expectation?

That expectation annoys me a lot in a broader sense, insofar as it’s laid upon all writers. All writers are expected to write characters that reflect their race. For me personally, I feel like being Asian-Canadian and Asian-American informs so much of my experience of the world I don’t know how to not write about it, at least right now. Once I was doing an event and the moderator asked me why I write so much about the patriarchy, and I said, I don’t intentionally write about the patriarchy. I don’t sit down and think, “I’m going to write about the patriarchy.” You write about the world as you see it and then it’s like, how can you not write about the patriarchy? That informs everything around you.

How do you think you’ve changed between For Today I am a Boy and The Lost Girls?

Writing is so much for me. It’s my favourite hobby, my livelihood, my therapy and my salvation. It’s everything, and that is so much pressure to put on one thing. [Before] I was making a living as a writer, it was easier in some ways because it wasn’t filling every role in my life. [Now], if the writing goes away, how will I go on? What will be the point of living? I think finding more things to love was important.

Also, for so long I just wanted to publish a book, that was the dream, that was the brass ring. Once that happened, I was sort of lost. I remember my mother told me she felt that way getting married. When she was a little girl she dreamed about getting married and then she got married, and it was like, now what? It was a big shift for me, I had to think about life in a different way, about my work and how much pressure I put on it.

What other things have you found to love, in addition to writing?

In the aftermath of the last book, one thing that was very helpful to me was dance. I had never, ever been interested in dance. I never did ballet as a kid. When I saw modern dance I was like, I don’t get this. I thought of myself as very clumsy and not a physical person. But Seattle is a big dance town. And the modern dance is just incredible. It’s so different than what I thought modern dance was, as being very inaccessible, abstract to the point of “I don’t know what’s going on.” I liked poetry from the time I was a little kid, so I don’t remember discovering it, but I imagine it must have been something like this: there’s this other way of expressing things that can’t be expressed in another way. I love going to [dance] shows and I do a little bit of it myself, but just here and there.

Also, seeing books again as separate from the whole machine of publishing. The first time you see how the sausage is made, it’s hard not to think about that every time you pick up a book or you walk into a bookstore. But eventually that dissipated and once again, books were the great love of my life. They were this wonder and portal. That magic came back.