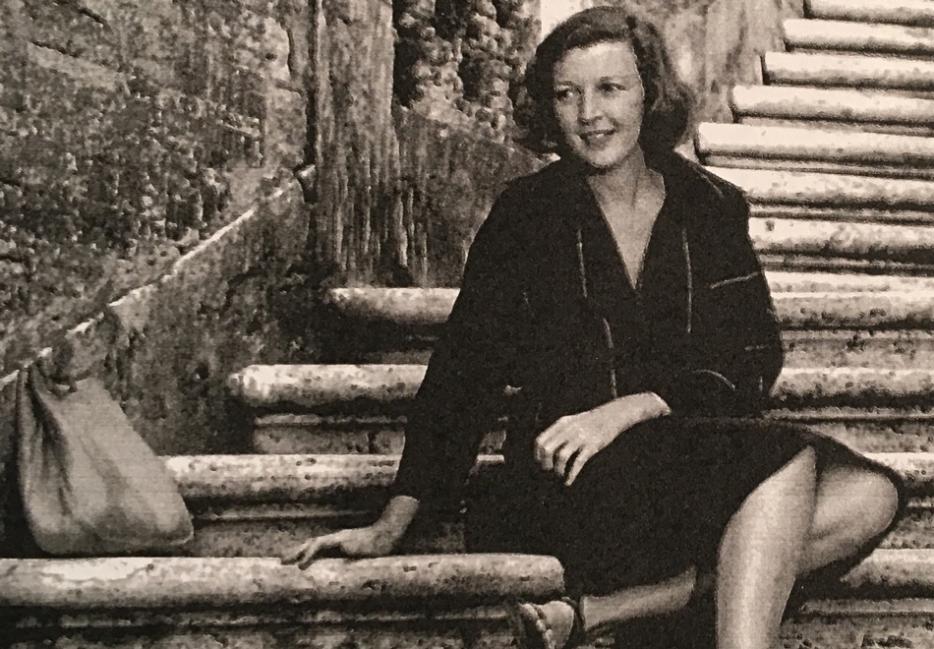

In November 1929, Martha Gellhorn was working “the mortuary beat” as a cub reporter for the Albany Times Union, having dropped out of Bryn Mawr one year shy of her degree. Edna Gellhorn, Martha’s suffragette mother, and Eleanor Roosevelt had been Bryn Mawr students together, so Mrs. Roosevelt invited twenty-one-year-old Martha to dinner at the Governor’s mansion where the Roosevelts lived and worked before FDR was elected president in November 1932.

Eleanor Roosevelt and Martha Gellhorn became close when Martha took a job in the fall of 1934 working for Harry Hopkins and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), reporting on the treatment of the unemployed all across America. Hopkins frequently sent Martha’s reports on to Mrs. Roosevelt. In North Carolina, for example, Martha observed, “The people who seem most physically hit are young girls…I have watched them in some mills where the work load is inhuman. They have no rest for eight hours; in one mill they told me they couldn’t get time to cross the room to the drinking fountain for water. They eat standing up, keeping their eyes on the machines…I found three women lying on the cement floor of the toilet, resting.” In one town Gellhorn observed latrines draining into a well, contaminating the source of drinking water. During her weeks in Massachusetts she saw people “facing the winter with husks of shoes bound up in rags,” a place where undernourished children were pale and wasting, their unemployed father distraught that he couldn’t do anything about it, at times wishing they were all dead.

Mrs. Roosevelt invited Martha to dinner at the White House so that she could explain the gravity of circumstances directly to FDR. Gellhorn remembered attending in a black sweater and skirt. She sat next to the president and explained to him the drastic conditions of whole families on relief who suffered from pellagra, rickets and syphilis. When asked in a late-in-life interview if she had been intimidated by FDR, Gellhorn replied, “No. I am capable of admiration, but not awe.”

Fired from FERA in September 1935 for inciting a riot among unemployed workers in Idaho, Gellhorn was invited by the Roosevelts to stay with them at the White House until she sorted herself out. Of those two months, she wrote, “The house was always full of chums and funny people [Alexander Woollcott, Alfred Lunt, Lynne Fontanne, to name a few] and it was one of the most pleasing and easygoing, amusing places you could possibly be in.” There she met visiting British writer H.G. Wells, who became instrumental in launching her writing career by arranging the publishing contract directly with Hamish Hamilton for her celebrated Depression Era book, based on her FERA work, The Trouble I’ve Seen [1936]. During the fall of 1935, while Gellhorn stayed in the Lincoln bedroom, she saw Mrs. Roosevelt frequently, because her rooms were in the same wing. The more she got to know her, the more she grew to respect and adore Mrs. Roosevelt.

By 1936, Gellhorn and Mrs. Roosevelt were intimate correspondents, confiding in each other and supporting each other emotionally. In an oral history interview she gave to the Roosevelt Library in 1980, Gellhorn said, “Mrs. Roosevelt’s letters were full of love. She loved me and she worried about me, and where I was, and what I was doing.”

The Trouble I’ve Seen would be published state side in September and Mrs. R. wrote about it in her nationally syndicated column, “My Day,” that ran six days a week from 1935 to 1962: “Martha Gellhorn has an understanding of many people and many situations and she can make them live for us. Let us be thankful she can, for we badly need her interpretation to help understand each other.”

*

Gellhorn was always interested in telling the stories of “the sufferers of history,” the ordinary people who behaved with grace and decency under extraordinary pressure. Her goal, “in a humble and fairly hopeless way,” was that something she wrote “would make people notice, think a bit, affect how they reacted.”

In June 1936 Gellhorn was in London, staying with H.G. Wells and his longtime lover Moura Budberg. Wells kept nagging Gellhorn that she had to write like him. He worked every day from 9:30 until 1:00 and insisted she ought to do the same in order to become a serious writer. So, to prove to him that she could, she “peevishly sat down in his garden and wrote” a fictional piece about a lynching in Mississippi. Gellhorn insisted it read “like a short story.” Nevertheless, editors assumed it was nonfiction. Wells placed it with The Spectator and it was subsequently published in truncated versions by Magazine Digest and Living Age. Gellhorn would soon wish that she’d “never seen fit to while away a morning doing a piece of accurate guessing.”

“Justice At Night” chronicles a happenstance journey in early 1930s Mississippi of a touring couple whose old car breaks down. They have to rely on local strangers to drive them to their destination. But, before they do, those redneck locals are determined to witness the lynching of a young black man, accused of raping a white woman landowner for whom he was working as a sharecropper, a widow, who “had a bad name for being a mean one.” The story is void of sentimentality, a hallmark of Gellhorn’s prose. “If you tell the reader what to think, that’s not very good writing,” she said. “It’s up to you to write it in such a way that the reader discovers it.”

Mrs. Roosevelt complimented the piece and encouraged this quality in a letter on November 7, 1936: “Do not get discouraged, because you have the ability to write so that one sees what you are writing about, almost better than anyone I know.”

Gellhorn responded from St. Louis on November 11:

Has Hick told you my latest bit of muddle-headedness. It’s very funny; and I was going to appeal to you to extricate me, but that seems too much of a good thing and I am going to be a big brave girl and tidy it all up by myself. It concerns that lynching article which you said you liked (your last letter and thank you for it.) The Living Age pirated that—simply annexed without so much as a by-your-leave; and then sold it to [civil rights activist] Walter White who sent it to you and presumably a lot of other people. He likewise wrote me a long letter and asked me to appear before a Senate Committee on the anti-lynching bill, as a witness. Well. The point is, that article was a story. I am getting a little mixed-up around now and apparently I am a very realistic writer (or liar), because everyone assumed I’d been an eye-witness to a lynching whereas I just made it up.

Paid $50, she “ceased to remember the tale and went on to the next thing."

The nearest Gellhorn came to witnessing a lynching was in 1934 when she was travelling with her partner Bertrand de Jouvenel. Their old Dodge broke down somewhere in North Carolina and they were picked up by a drunk on his way home from a “necktie-party.” As she wrote to Mrs. Roosevelt, “He made me pretty sick and later I met a negro whose son had been lynched and I got a little sicker.”

Mrs. Roosevelt responded on November 30, “… you had just enough actual fact to base it on for your rather remarkable imagination to do the trick and make it as realistic as possible! I do not think Walter White will care as long as you do not spread it around that you had not actually seen one.” Gellhorn wrote to White to tell him that she was “only a hack writer” and not “a suitable witness” for his excellent cause. Mrs. Roosevelt assured her in a letter on December 10 that Gellhorn had accomplished what White had wanted, wishing “more people had the ability to visualize a lynching” as she had done, however upsetting. For truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it, as Flannery O’Connor wrote.

*

In what may well be the first letter to anyone in which Gellhorn mentions Ernest Hemingway (then an already-celebrated American novelist to whom she was married from 1940 to 1945), she wrote to Mrs. Roosevelt on January 8, 1937, “I’m in Key West: to date it’s the best thing I’ve found in America. It’s hot and falling to pieces and people seem happy.” She was working on finishing a novel [Peace on Earth, never published],“praying to my own Gods (they both look like typewriters) for some wisdom.” She insisted, “Either this book must be just right and as alive as five minutes ago, or it won’t be a book and I’ll sit and nurse a lost year as best I can.”

She confided, “I see Hemingway, who knows more about writing dialogue (I think) than anyone writing in English at this time. (In a writer this is imagination, in anyone else it’s lying. That’s where genius comes in.) So I sit about and have just read the mss of his new book and been very smart about it; it’s easy to know about other books but such misery to know about one’s own.” And, then turned to worrying about world politics: “If the madman Hitler really sends two divisions to Spain my bet is that the war is nearer than even the pessimists thought.” She closed, writing, “I love you very much indeed, and I am always glad to know you’re alive.”

A week later Mrs. Roosevelt wrote, “Do not be so discouraged. I do think you ought to go right ahead and write the book without rehashing all the time. You do get yourself into a state of jitters. It is better to write it all down, and then go back. Mr. Hemingway is right. I think you lose the flow of thought by too much rewriting. It will not be a lifeless story if you feel it, although, it may need polishing.” She continued, “My book is going along very slowly just now as life is entirely devoted to social duties—things which I like just about as well as you like St. Louis.” And ended with an open invitation to stay at the White House, “Of course, you may come here at any time you feel like it. Much love, Eleanor Roosevelt”

From March through May 1937 Gellhorn was in Spain, with Hemingway, at the Hotel Florida, where she wrote and submitted her first piece of war correspondence about the people of Madrid, published in Collier’s as “High Explosive for Everyone.” She returned to New York City at the beginning of June to help finish The Spanish Earth, the documentary they both worked on with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens. Gellhorn arranged with Mrs. Roosevelt to show the film at the White House in early July.

After the screening, she wrote on July 8 to thank her, knowing that both Mrs. Roosevelt and the president were sympathetic to the plight of the Spanish people: “I am so glad you let us come because I did want you to see that film. I can’t look at it calmly, it makes it hard for me to breathe afterwards.” The shelling scenes in Madrid, with “women choking and wiping their eyes with that dreadful look of helplessness,” seemed all too close.

Gellhorn was keenly aware of the kindnesses Mrs. Roosevelt extended to her and concluded, “It’s awful hard to thank you adequately for all the good things you do, only you know how grateful I am don’t you! And how much I love seeing you and the President… I hope I can see you again before I sail. Love, Marty”

Early in 1938, stateside, Gellhorn embarked on a cross-country speaking tour to raise funds and awareness about the civil war in Spain. She became very ill and wrote on February 1, “my doctor says either stop it or you will crack up… I am really more busted than I have ever been.” Gellhorn realized that “if one is a writer, one should be a writer, and not a lecturer.”

Mrs. Roosevelt wrote back on February 8,

I am glad you are going to write Spain out of your system. Writing is your best vehicle and you ought to do a good piece of work… No one can keep calm when they have seen the things you have seen and felt as you feel,” imploring “get well and try to forget temporarily the woes of the world, because that is the only way in which you can go on.

By March 1938 Gellhorn was recovered enough to return to Spain and wrote en route aboard RMS Queen Mary:

…The news from Spain has been terrible, too terrible, and I felt I had to get back. It is all going to hell… I want to be there, somehow sticking with the people who fight against Fascism… I do not manage to write anymore, except what I must to make money to go on living.” An early anti-fascist, Gellhorn wrote in disbelief about Hitler’s influence, noting, “The whole world is accepting destruction from the author of ‘Mein Kampf,’ a man who cannot think straight for half a page.

As ever, Gellhorn wished she could see Mrs. Roosevelt, but warned that she would not like her much because she had “gone angry to the bone.” She thought that “now maybe the only place at all is in the front lines, where you don’t have to think, and can simply (and uselessly) put your body up against what you hate.” The war in Spain was one kind of war, but “the next world war will be the stupidest, lyingest, cruelest sell-out in our time.”

Mrs. Roosevelt responded on April 5,

Dear Marty,

I was very sorry to hear you had gone back to Spain and yet I understand your feeling in a case where the Neutrality Act has not made us neutral.” Always a citizen of the world, she concluded, “The best we can do is to realize nobody can save his own skin alone. We must all hang together.

Affectionately,

ER

She understood suffering and what the cost was in human pain, misery, fear, and hunger.

Gellhorn travelled to Czechoslovakia to report on the German Jewish refugee crisis for Collier’s. She wrote several letters to Mrs. Roosevelt, including one dated October 19 in which she raged that, “There may be no hope of saving Europe, but democracy must be kept alive somewhere. Because it is evident that war itself is better than Fascism, and this even for the simple people who do not care about politics or ideologies. Men just can’t live under Fascism if they believe any of the decent words.” She explained, “I hate cowardice and I hate brutality and I hate lies. And this is what we see, all the time, all over the place. And of these three, maybe the lies are worst. Now Hitler has set the standard for the world, and truth is rarer than radium.” Trying to make room for a little hope, she said, “Please give my respects to Mr. Roosevelt. Will you tell him that he is almost the only man who continues to be respected by honest people here. His name shines out of this corruption and disaster, and the helpless people of Czechoslovakia look to him to save the things they were not allowed to fight for.”

With that letter Gellhorn attached a report called “Anti-Nazi Refugees in Czechoslovakia,” an impassioned piece that Mrs. Roosevelt not only read, but gave to the president, noting on November 15, “I hope the day will come when you can write something that will not make one really feel ashamed to read it.” And, trying to bolster Gellhorn’s belief in some goodness, she closed, “I am afraid we are a long way from any real security in the world but it is curious that, in spite of that, we all go on from year to year with the hope that some day things will improve. Affectionately, Eleanor Roosevelt.”

By the end of 1938 Gellhorn had returned to New York, where her family would gather together to celebrate Christmas, and where she had hoped to lunch on December 20 at the Biltmore with Mrs. Roosevelt. Her ship was late docking and they missed each other. In a telegram sent on December 22, she wrote, “Terribly disappointed to have missed seeing you. Boat was day late. Will you have time later and will you let me know. Have saved up nine months conversation. Merry Christmas. Devotedly. Marty”

When her maternal grandmother died unexpectedly on January 9, 1939, Gellhorn returned to St. Louis to support her mother and confessed to Mrs. Roosevelt the next week that she was pretty disgusted with herself for abandoning her causes while she pursued her work as a journalist, “which, in the end, is to my own benefit.” She noted that what she found wanting in herself she could always admire in Mrs. R., “your unwaveringness, the way you carry on all the time, without fatigue or doubt or discouragement.” Gellhorn observed that her mother Edna had those same characteristics, and that, perhaps “women like you are just better quality than women like the rest of us.”

Mrs. Roosevelt replied on January 26,

My dear Martha,

I don’t wonder you feel as you do. Human beings have never been as fine as they should be except individually and in great crises…

People rise to great crises. That is what the Spanish people are doing too. That is what the Czechs would have done if they had been given a chance. But when people feel safe and comfortable they are apt to feel a way to go, as a good part of the United States feels…

Stop thinking for a little while. It is good for us all at times, and there will come a chance to do all the things for your country that you want to do. I have an idea that your younger generation is perhaps going to be willing to make some sacrifices which will really change much of today’s picture.

Affectionately yours,

Eleanor Roosevelt

*

When donating her letters from Mrs. Roosevelt to the Boston archives in 1965, Gellhorn wrote that Roosevelt “was of course harshly schooled in politics and people—the art of the possible using imperfect material. She was incredibly tolerant of human failing; she knew how slow all change is…but she understood the mechanics of power (as I never have) and knew that great injustices were not apt to be quickly righted, if at all.”

By 1954, Gellhorn was re-married and living in London and Mrs. R. was “sort of vanishing” from her life and she was cross about her absence. Mrs. Roosevelt “showed up in London, staying at Buck House with the queen” and Gellhorn got in touch with her. Since FDR’s death, Eleanor Roosevelt was in her own right a great world figure. During that visit she carved out an evening in her schedule to join Gellhorn and her husband Tom Matthews for dinner at their home, just the three of them. And, when asked why Gellhorn rarely heard from her those days, she said, “But darling, you’re all right now; you don’t need anything; you’re looked after.”

On her 54th birthday, Gellhorn read of Mrs. Roosevelt’s death in the morning paper, and “felt that one of the two pillars that upheld” her “own little cosmos had vanished.” Roosevelt was “the finest conscience in America, the most effective one too, a woman incapable of a smallness or cheapness, and fearless.” Martha would write decades later, that seeing Mrs. R., “no one would fail to be moved by her; she gave off light, I cannot explain it better.”

All images and correspondence quoted between Eleanor Roosevelt and Martha Gellhorn are from the Martha Gellhorn Collection, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.