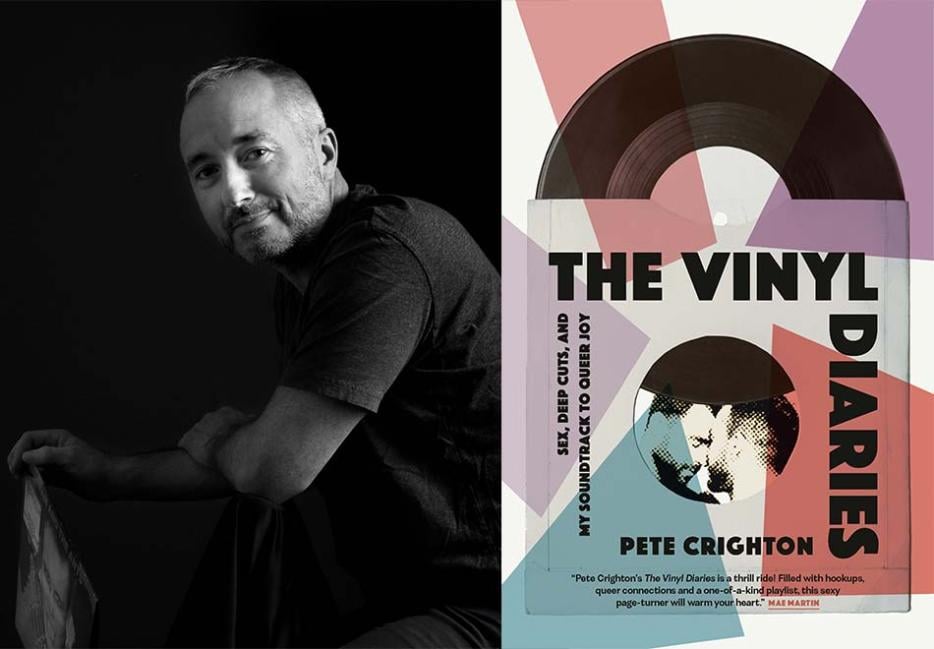

Oh to be queer in the age of PrEP, Grindr, Chappell Roan, and Kristen Stewart. Thanks to decades of fighting (and despite loathsome ongoing attempts to undo our progress and erase our identities), young LGBTQ+ people now come out to a rainbow-adorned corporate-sponsored month of debauchery celebrating our relationships and identities. Still, those of us who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s bear scars from a time when the closet was the norm and the word “queer” was a slur. Back when writer Pete Crighton was waking up to his own sexuality, gay men around him were falling victim to HIV. The public reaction to the virus—and gay people—was largely stigma, panic, and cruelty. With no community and few role models, music became a safe space for self-expression and joy. Crighton's new book, The Vinyl Diaries (Random House Canada) is a loving account of how Crighton, now in his 50s, found new musical horizons and a pretty hot sex life—with the help of his massive record collection.

Nicole Pasulka: You write about being scared of AIDS as a closeted young person and say, “instead of educating myself, I dove into my record collection.” Why was music such a refuge when dealing with the AIDS epidemic and your queerness?

Pete Crighton: It was an escape. Before I could even talk, I would react to music and dance and move. According to my mother, certain songs would sweep me away. So, when I did actually want to escape as a teenager, that pleasure centre was already there for me and it was the natural place to go.

What was your relationship toward what was popular? And how did the music you liked inform your identity?

We were a lucky generation. We were exposed to so many genres on radio and TV. At that age, it was easier for me to understand what I didn’t like than what I did. Cyndi Lauper, Madonna—if the popular kids were into it, I wasn’t. I liked Depeche Mode, The Cure, The Smiths—even if I couldn’t admit what was going on, I identified them as not mainstream.

Yeah, people forget that back then, it was so uncool to be mainstream. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, a lot of the musicians you were drawn to were queer or queer-coded, but closeted. Was this confusing? Did you wish they were out, or was that unfathomable?

At the time it was so confusing. Freddie Mercury never came out officially. Elton John married a woman. It was like, what is happening here? They were so clearly gay, everyone talked about them as such, but they wouldn’t say it out loud. I thought, well, if they aren’t gay, why should I be? They have money, power—I’m 15, I have nothing. Jimmy Somerville of Bronski Beat was the only one who was really out. A few more people like him would have made my life easier and given me an example of what a queer person could be in that time.

How does it feel to see so much queer representation today?

It’s amazing that the world has opened up and allowed that to happen. It’s funny—even today, queer artists still want to be popular artists. There isn’t that energy of punks overturning the system. I would love a musical revolution that flips the table and goes, “no, we’re not playing this again.”

You spent your 30s in a monogamous relationship and then started experimenting with the apps and casual sex in your 40s—largely with younger men. I think this is a familiar path for lots of men who grew up fearing AIDS. Did this shift affect how you listened to music and what you listened to?

Around that time, my love of music and my record collection became a way to communicate instead of a way to hide. The genesis of the book was playing these records for lovers and telling them about queerness in the ’90s, and hearing about their experiences in a different generation. It sparked a great dialogue across generations. I’ve always consumed new music, but those younger lovers came to me with artists I’d never heard of otherwise.

For example, this one guy, Mike, was like, “Mitski is the voice of a generation.” I was like, “whoa, okay, I’ve got to pay attention to that.” I’d never given Mitski that much thought, but whether you like it or not, it’s broadening your perspectives and access to art.

And at an age when people assume one should or would be settled down monogamously, your sex life expands. Why do you think you were able to overcome your fear of casual sex?

It was a little bit of a “midlife crisis,” where you just think, oh my god, I’m not doing this anymore. I’ve lived in fear for so long, and I’m going to explore this. I’d be lying if I didn’t say the shift in sexual health and access to PrEP—and particularly more knowledge about how HIV/AIDS is transmitted and how it can be avoided—made things feel a little more safe to my mind. The idea of safe or safer sex was so loaded back then. We believed all this stuff that we were told—that tended not to be true. There was so much misinformation and no support or visibility.

You write a lot about your interest in younger guys and the excitement you found in intergenerational relationships. Beyond the boys being fun and cute, what was the appeal? Being a mentor? Their relative openness about sex and identity?

I wasn’t actively searching out younger men, but I was shocked to discover that younger men found me sexually interesting. I was like, “What?” I hadn’t heard that story in culture or popular literature. So that was an awakening.

What I found in younger guys was a freedom in talking about their sexuality and in having sex—something that me and a lot of men in my generation didn’t have and still don’t. There’s something beautiful about being witness to and participating in that freedom.

Can you be with someone who likes different music than you? Who doesn’t like music? How important is it that your tastes be aligned?

That’s a hilarious question. There’s got to be some overlap for sure. When I was in an 11-year relationship, we talked about TV people vs. music people. That relationship was defined by that separation. My partner was very much a TV person, and I was very much a music person. That is a chasm that wasn’t traversable. There has to be some love of music for me to feel good about the partnership.

You describe yourself as “queer,” a word many men of your generation feel some discomfort with. Why have you embraced it?

For me, it’s about that attraction to the subversive stuff and living outside the norms. I don’t see it as a slur—more of a badge of honour.