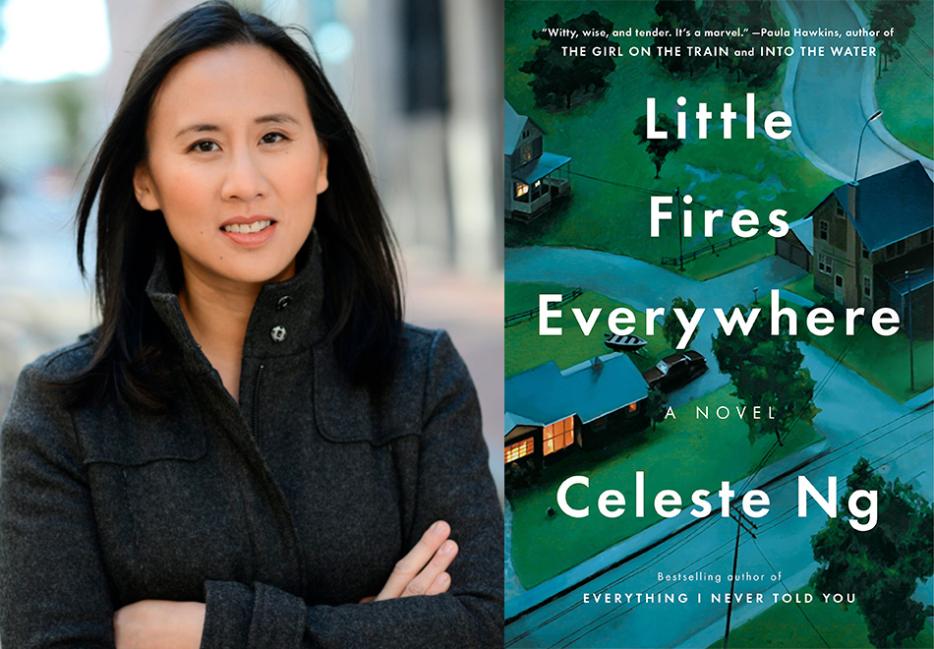

On the first page of Little Fires Everywhere (Penguin Books), Celeste Ng gives away the ending. The Richardsons' mansion is on fire, flames shooting out of each of the six bedrooms. The youngest Richardson, Izzy, is the arsonist culprit and has already fled Shaker Heights, the peaceful, progressive suburb of Cleveland.

For the rest of the novel, Cambridge-based author Ng explores the uncomfortable truths of racism, classism, identity and the privilege of who gets to be a mother. Set in Ng’s own childhood hometown, the book centers on Elena Richardson, a rule-following, do-gooder reporter at the local newspaper obsessed with maintaining the façade of a perfect life, her defense attorney husband, and their four high school-aged kids, Lexie, Trip, Moody and Izzy. Elena’s life is overturned when the enigmatic, status-quo-busting Mia Warren and her daughter Pearl move into the Richardson’s rental property, and the two mothers end up on opposing sides of a custody battle between a desperate Chinese waitress and a rich white couple.

Little Fires Everywhere is Ng’s follow-up to her best-selling debut, Everything I Never Told You, which follows the lives of the mixed-race Lee family in suburban Ohio. While Everything I Never Told You showed the blatant racism against Asian-Americans in the 1970s, Little Fires Everywhere scrutinizes the illusion of a post-race America.

Samantha Edwards: Why did you want to set the book in your hometown, Shaker Heights?

Celeste Ng: I had gotten to that point in my life where I had been away from Shaker Heights long enough that I was able to look back and see it with a bit of clarity. [When I started working on Little Fires Everywhere] I had been away for ten years and I started to realize a lot of things that I thought were normal based on my hometown were actually nothing of the kind. Things as small as rules about how you took your garbage out or how you had to mow your lawn. When I got my own house, I realized it was OK if we didn’t mow the lawn and we were allowed to put our garbage on the curb.

But I also realized how unusual Shaker Heights was in a lot of positive ways. It’s very much an idealistic sort of town. It’s racially diverse and fairly racially integrated. The community is so aware of race there was a race relations group at the high school that went to work with the fifth graders. I was fascinated by that tension between the idealism that runs the town and the nastiness of the world we live in, so I wanted to try and write a story about that.

Everything I Never Told You is also based in a small town. What’s the appeal of writing about small towns or suburbs?

This gets into deep psychological territory. I’m a city person. One thing I love about the city is that it affords me a certain level of anonymity. You get a lot of choice about who you interact with. I remember the first time I went to New York City, I was really worried—“am I going to be dressed well enough?”—and then I went and no one cared, no one noticed me. A suburb isn’t quite a small town, but it’s sort of in this middle area where there’s a lot of different people but you don’t have the same anonymity as a city. There is a very defined community and a very defined base in which that community has to live and get along. There’s something about it that fascinates me. I grew up in the suburbs, so it’s a place I feel like know really well. It’s a fun place to dig into.

One of the biggest distinctions between Mia and Pearl and the rest of Shaker Heights is their economic class.

It struck me that when I was in high school there were a lot of class distinctions in Shaker Heights, but I didn’t quite know what to make of them until I got older and moved away. Shaker Heights is known in the Cleveland area to be very affluent, so if you tell people you’re from Shaker Heights, they assume you have a lot of money. But the thing is, there are also a lot of basically middle class households.

As a kid, I noticed who had the real Keds and who had the knock-offs. Who had the brand name coat and who has the one that looks like it. Who goes skiing and and who doesn’t know how to ski. My family never went skiing and it was kind of a fashion thing to go skiing on the weekend, and then come to school with the lift ticket on your jacket. I think it was only looking back as an adult that I could look back and go “Oh, that was a class difference.” I didn’t go to sleepaway camp, where, at least in the states, there’s sort of a class marker as well.

When we see Pearl going into the Richardsons' house for the first time, she’s just in awe of all their stuff and noticing all these tiny things. You realize that for Lexie, Tripp, Moody and Izzy, these are things they don’t even notice.

Exactly. It’s part of the scenery for them. That was an experience I had as a kid, partly because my parents were immigrants so they were concerned about getting us through school and saving money to buy a house. My parents were also scientists so they didn’t care a lot about decorations, they just wanted the house to be nice and clean. I’d go to friends’ houses and see all their little knick knacky souvenirs and their enormous furniture. My parents liked functional things like sofa beds.

I found it really interesting how in Everything I Never Told You, which was set in the 1970s, the kids felt like outsiders because they were mixed. And then in this book, set in the 1990s, mixed kids are seen as something desirable, the perfect amount of exoticism. Lexie says to her African-American boyfriend, “If we ever had kids, they would be adorable because mixed babies always come out so beautiful.” I think as there are more interracial couples and therefore more multi-racial babies, we’re also starting to see this pushback against the idea that mixed babies are going to save the world. Full disclosure: I’m half-Japanese and half-Caucasian.

Full disclosure: my husband is white so I’m the mother of a mixed kid. I remember that in the '90s, if I was dating a white boy my friends would say, “if you ever have a baby it’s going to be so cute because it’s mixing up the gene pool.” At the time, I was like “OK, cool.” Now that I’m a little older and our discussion about this topic has become more nuanced, I feel resistance to the idea that all you have to do is have two people in an interracial marriage and then their children will magically solve all the race relation [problems]. One of the reasons I wanted to set the book in the '90s is because it’s just far enough for us to see it with a little bit of perspective, but it’s still close enough we can still remember that era. There’s this sense of how far we’ve come and how far we’ve not come. This whole idea of “Oh I don’t see race,” which I remember being very much the way we talked about race at the time. Now we see that as not necessarily a positive thing.

The Richardsons view themselves as really progressive people who don’t see race, but then they say a lot of things that are subtly racist or made me feel uncomfortable. Like when Lexie is looking at [the baby] May Ling’s skin and describes it as the colour of café au lait. I feel like every woman of colour has had their skin described as the hue of a hot beverage at least once in their life.

Exactly! What I hoped readers would get out of that is this little moment of slight cringing but also laughing. “Oh you’re chocolate-coloured, you’re mocha, you’re biscuit-coloured.” Why are we always food? And it’s so often a hot beverage, which is so weird.

I read in another interview that when Everything I Never Told You came out, you were a bit concerned about being pigeonholed as an Asian-American writer who specifically wrote for an Asian-American audience. Are you still afraid of that?

My feeling about that has evolved and I’m privileged that my experience got to evolve because that book got embraced by not just Asians, but wide a swath of the population. I think it gives me a little bit of freedom that a lot of Asian writers haven’t been given, and should be given. I was worried that people were going to say, “Oh this a book only for Asian people.” I was really happy when non-Asians would come up to me and say, “Look, I’m not Asian, but this is my relationship with my mother” or people who were mixed race, but not mixed race Asian, would say, “I really emphathised with this family.” That meant a lot to me but I feel like in a lot of ways, that was a lucky fluke, I was very fortunate that happened. Now maybe people won’t pigeonhole me, but it happens to so many other Asian writers. If you write about Asian characters you are assumed to only write about Asian issues. That’s very frustrating to me. It’s like you’ve been assigned a beat and you’re not allowed to stray from it. It’s something that doesn’t happen to white male writers. You’re not going to say, “How come you’re writing about white men again?”

The baby at the centre of the custody battle is Chinese. Why did you want the baby and her mother to be Chinese?

I wanted to tackle the experience of being a Chinese-American in a community where we think mostly about black and white. In the US, we’re thinking about race largely in terms of black and white. As an Asian-American, I’m in this very weird middle-ground. I don’t fit into that binary system, and yet at the same time, I’m clearly affected by both. I wanted to put an Asian woman and an Asian baby at the centre so I could look at the experience. They’re at the centre of this debate, and yet they’re the ones with the least agency.

At one point in the book, Mr. Richardson says that East Asian men can either be “socially inept or incompetent, ridiculous or slightly buffoonish, but not angry and powerful.” I see that [stereotype] exist in pop culture. Like, why can’t an East Asian man be cast in a Hollywood romantic comedy?

I absolutely completely agree. That’s one of the reasons I was glad I got to put that in the book because I feel like obviously there are lots of limitations on what society is going to take from East Asian women, but I feel like East Asian men even have a whole different set of limitations.

Kevin Kwan’s book Crazy Rich Asians, which is about families in Singapore, is [being turned into] a romantic comedy with an all Asian cast, which is kind of amazing. The last time there was a [Hollywood movie] with an all Asian cast was The Joy Luck Club, which came out in 1993. It’s quite startling that for whatever reason, Asian men aren’t considered for a such a wide swath of roles, they can either be the funny sidekick, or the evil bad guy/martial arts hero, but they can’t just be normal people.

I didn’t want to ask you so many race questions, but I realized I just threw them all out there.

It’s something that I’m really interested in too and frankly, at least right now, I’m always happier when people ask those questions than if they don’t because we have not reached the saturation point of that conversation. We have not reached the point where we don’t need to talk about it anymore. I never planned to be any kind of spokesperson, but my feeling is if people want to talk to me about it and they’re going to listen, I will.