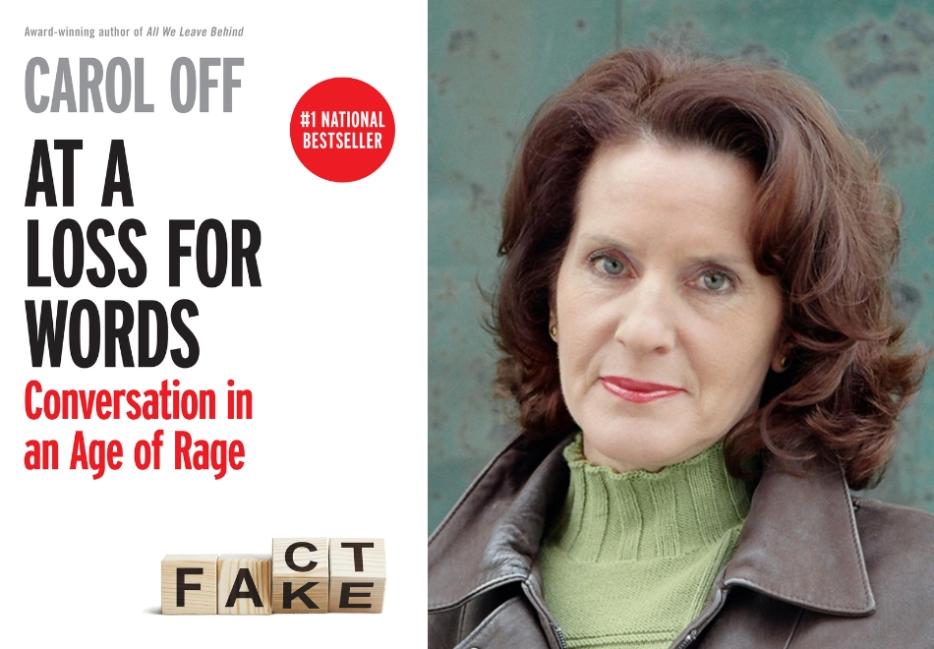

Carol Off has, for decades, been one of Canada’s most prominent journalists. As a reporter, she covered the breakup of Yugoslavia, the aftermath of the genocide in Rwanda, and the war crimes trials of the 1990s. In 2000, she published her first book, The Lion, the Fox and the Eagle, a triptych portrait of three Canadians at the centre of those events. For sixteen years, Off hosted perhaps Canada’s best-known radio show, As It Happens, on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

In At a Loss for Words, her fourth book, Off grapples with the ways language has been weaponized and manipulated in our current era of right-wing populist politics. The book is structured around six words—Freedom, Democracy, Truth, Woke, Choice, and Taxes. She uses each as a jumping-off point to both dissect the history of and present context around ideas like fascism, dissolution, demagoguery, and the politics of information.

I spoke with Off twice by phone this fall, once before the American election, on November 5, and a second time shortly thereafter. Our conversations have been edited for clarity and length.

Richard Warnica: As I was reading the book, I was thinking about this moment in Iowa in 2016. I was covering the caucuses, and I went to this really early Trump rally; there were hundreds and hundreds of people there, lined up in the snow. My instructions going down had been: don’t spend too much time on Trump, because the Trump story will be over soon. Being inside that rally and seeing people almost falling over the banisters to get closer to him was the moment I realized something had changed. Was there a similar “aha moment” for you?

Carol Off: There were a series of them. I think an aha moment for me was seeing things that reminded me of other places, other countries I had been to, where suddenly there were these charismatic figures who could sweep people up [and convince them] to do anything. They captured them emotionally, irrationally, and once they had done that, they had tremendous authority over them. I saw it in Bosnia. I saw it in Kosovo. I wrote about it in Rwanda when I did the book about Roméo Dallaire, and I saw it in Russia when I covered the Putin elections. I could see what this kind of cult of personality could do. When I could see it happening in the United States, it didn’t surprise me, but it certainly alarmed me, and I thought, Is it possible that people in a sophisticated democracy are vulnerable to this, are not immune to the power of this kind of figure?

One thing I found, I don’t want to say enjoyable, because I don’t think “enjoying” is the right word, but compelling maybe, in the book, was the connections you drew between your reporting in the Balkans and what has happened in liberal democracies over the past eight years. When did those connections start to click for you? Was there a moment where you were watching Trump and thought, “I’m seeing echoes of Milosevic here?”

The person who connected all these things for me was my very good friend Gordana Knežević, who was the person I turned to in Sarajevo when I wanted to understand what was going on. The war in Bosnia was always regarded as last cry of the wars of the 20th century. It was the end of the Cold War. It was sort of a last hangover, in Yugoslavia, of the war against fascism, against totalitarianism. Gordana was the one who alerted me to the reality that it was not the last war of the 20th century. It was the first war of the 21st century.

The reason I wrote a book about words is because it begins with language. It begins with rhetoric. And Gordana describes this incredible moment when she is in her house and she’s listening to the radio in Sarajevo, and she’s hearing Radovan Karadžić and he’s on the radio, and he’s basically saying, “We can’t live with these other people.” And it was an extreme thing to say, “We can’t live with Muslims.” She realized something bad was going to happen. Once that’s been broken, once that line has been crossed, there’s no stopping it.

What we’re seeing, especially now, in this election, in the past couple of months, is this extraordinary rhetoric of hate. And it’s fascistic. There’s no question that what J.D. Vance is saying—the attack they launched against Haitians in Springfield, Ohio, the speeches that we’re hearing these last weeks of the campaign from Trump, which demonize the other, demonize immigrants, preach this idea that we have to round them up and deport them—the language they are using is fascistic. These were things that Gordana noted very early on in Yugoslavia, when she realized that things were going to go really badly soon. And it’s happening actually more rapidly than I thought it was in the United States.

You quote the political scientist Brian Klass at one point in the book, who argues that “when democracies start dying … they usually don’t recover.” What did you take from that quote?

I think that the biggest signal of that trend, and I can’t see how it will recover, is going on in Hungary right now with Victor Orbán. That’s why I spent so much time in the book describing not just what Victor Orbán has done to Hungary, which is to take a robust democracy and turn it into a quasi-dictatorship, but how he has become such an influential figure in the minds of others. A large part of the conservative movement in the United States is now in bed with Victor Orbán. The people behind Project 2025 have a close affinity with Victor Orbán. The people who are running the Republican Party are really drawn to the ideas of Victor Orbán, who says that democracy is an obsolete idea, that democracy didn’t work because it includes too many people, that what we need is to have a country, in Hungary, that is represented by “the strong people.” And in Orbán’s case, that means white Christians. He sees people who are immigrants or women, or LBGTQ, as being lesser citizens who are not entitled to the same privileges of, as he calls it, “his” society. He has created what he calls an illiberal democracy, which does not extend the rule of law to all its citizens, but just to those whom he regards as privileged. This is exactly what Mussolini and Hitler talked about. So this idea that democracy doesn’t recover? It might, in Hungary, but it will take a very long time. And the best thing other countries can do is stop it from going in the first place.

You write a lot about Pierre Poilievre in the book. I’m interested what you make of him and how you’d compare him to other conservative leaders you’ve covered.

I think people make a mistake when they say that he’s Trump. There’s no one like Trump, who is a really frightening, charismatic character. Poilievre doesn’t compare with that. I think Poilievre has found this language of populism and demagoguery to be useful to him. I don’t know if he actually believes it. I would like him to read this book. He won’t, probably. But he has to realize where this goes. It’s a fast way to power, to turn to this populist demagoguery, this us-against-them narrative which he has been running on, that classic populism, that he represents the people, that he is going to fight against the others— those enemies which are never in populism clearly defined.

The term Poilievre uses for that other is “the elites.” Who knows what the elites are? He uses “the gatekeepers,” another vague term, “the globalists,” which in the international community so often has hints of being the Jews, right? We know that’s how it’s been used elsewhere. And then he talks about the woke menace. Again, as I write about in the book, “woke” and “wokeism” are these convenient euphemisms to disguise all kinds of racism, Islamophobia, homophobia. And I don’t know if that’s what he means, but it doesn’t matter. He doesn’t have to spell it out. I don’t know if he genuinely despises those others. But he is using words that give codes to those who do.

I think he sees this as a route to power. It doesn’t have to mean anything, as long as the rhetoric appeals to something irrational, emotional, sentimental. That’s how demagoguery rules. Whether he is actually this figure, if he actually believes this, I don’t know.

I do think he’s definitely very libertarian. He’s said that from the beginning. He’s studied it. He is an adherent of it. He believes in the marketplace determining our course. We’ve had this before, but his libertarianism extends, really frighteningly, to media, which he has said should be defunded. But that’s not even the worst part of it. What he’s talking about in larger terms is that the media should be turned over to market forces, that what you and I are able to consume or learn about from the news in our country and our communities should be subjected to market forces. If you turn our media over to market forces, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg are going to decide what you learn about your community, and you for sure won’t be learning about what’s going on at the school board.

So that’s one thing that scares me. The other thing that that he says that scares me is that, I will make sure that everything that I—and he always says “I,” not “my party,” or “my government”—I will make sure that everything I pass is constitutional, and you know what I mean by that. And what he means by that is that he will use the notwithstanding clause to get his policies through. What is it he wants to do in government that will require him to override the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, something that means a great deal to many people in this country, including me?

So those are the two things that I worry about the most. We are already, in many communities, living in news deserts. And as I tour with this book, I’m finding so many places where they just have no more sources of local news, of information. They have nothing. The only thing left, quite often, is the CBC, which he says he will dismantle. So when you live in a news desert, and then you have a populist leader who is appealing only to emotion and is suspicious of anybody who is independently asking questions, and he also plans to override Charter rights, that starts to become a bit more of a scary scenario to me.

I imagine that if Poilievre or a Conservative supporter read the book, the reaction would be, Here’s a longtime CBC journalist, who is talking to Michael Ignatieff and Margaret Atwood and now telling me what to do, and they’re going to close the book and feel like it has confirmed their pre-existing beliefs rather than challenging them. You spent so long on air, speaking to such a wide swath of the country. How do you speak now to people who are less inclined to even listen to your arguments?

People on the hard ideological left are just as disinclined to listen to or read what I’ve written in this book, because they believe it’s pointless to try to engage the other side. The hard left and the hard right believe, or maintain, that to actually have a conversation with the other side is to give them a platform. They don’t want a conversation. They don’t want to build any bridges between differences. I say in the book that the reason why I’m looking at the hard right and its influences right now is because that’s where the power and the money reside right now. There’s nothing on the left that compares with that. I mean, cancel culture is the most powerful tool they have in the toolbox. It doesn’t amount to anything.

I’m not interested really in appealing to either of those sides, because I think that it just uses too much energy to try to pull people in who have decided that there is nothing to be talked about. They take no prisoners. I think that the vast majority of people in between, the frustrated majority, they may not agree with my politics, but they are looking to build bridges. And I have made very clear where my politics come from. That’s why I told stories about my family in the book. Those are my values: liberal democracy, the constitution, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. And there’s a wide range of people, on the right and the left, who support that, a large number of us who are nostalgic for the days of Brian Mulroney.

I remember covering Brian Mulroney’s time in office, and we [the media] were highly critical of his conservative policies. Now they just seem so middle-of-the-road and moderate. They were pro-science. They were pro-facts. Those politicians would take interviews from us. They didn’t like it when they were challenged, but you could actually talk to them. There was not the hatred of the other the way there is now.

I think that there are large numbers of people on the right and the left who are conservative, who are liberal, who are not into socialism or libertarianism. There is a wide range of them that are with still within that liberal democratic scope, that want to work things out and have different ideas and different ways of doing it, that are not outside of the spectrum of normal politics.

But again, when I say liberal, it’s not a partisan liberal. It’s liberal democracy, this idea of inclusion, of a government that is taking care of everyone, whether they voted for them or not, because the law requires them to do that. So I think that, yes, I am probably more left-leaning than some people who might read this book, but I think that there is a lot in the book for everyone to start to think about, including my biggest message, which is just to listen very carefully to the language around you, to who’s using it and how they’re using it and what their motives are.

I’m interested in your faith in the enduring middle, this idea that there is still the broad centre that is willing to listen. Where does that faith come from?

I think that we are social animals. I think that our survival gear, our exoskeleton, is being social, is working things out as societies, not because we’re nice people, or good people, but because that’s how things function best. We’ve learned, certainly over the past hundred years, that to avoid the worst effects of what we saw in the last century, we need to work things out in a very open, rational, and accommodating way. I think that’s what we want. We want stability. People do not want to live in this world of rage. It’s not a good place to be. And so that’s my faith. It comes from that sense that most people would like to live in a place where we get along and we listen to each other, whether it’s at the dining room table or it’s in the houses of Parliament or if it’s on the international stage. We like the idea of working things out.

There are these wedges that are being driven between us to make us feel that we can’t get along, we can’t trust the other, that there are shadow forces working against our interests. This is frightening and appealing, and it’s again how demagoguery works. It probably began much earlier, but it really took off during COVID. Family members were dying, and people were getting sick, and we didn’t know where it was coming from or who was behind it. And in many cases there were doubts being sown as to whether or not it really was what they said it was. Was it a conspiracy? Was it the Chinese? Was it Bill Gates, who was implanting chips in your brain if you got inoculated against the disease? We know that some of that stir came from various people trying to gain power through our fear and insecurity. But hugely it came from overseas, from sources in Russia, where they played on those ideas.

We came out of that era feeling really shaken and really insecure, and nobody has come forward since to reassure us. We’ve seen Pierre Poilievre exploit that, but I haven’t seen anything from the Liberals that encourages me either. What I saw during the whole era of COVID from the Trudeau government was this technocratic response. Here’s the science, and if you don’t believe it, well, screw you. There was no heart to it. There was this lack of understanding of what people were going through, and I think that was easily exploited by others, leading right up to the Freedom Convoy in Ottawa.

I think people want to return to a time when they can trust each other, when they can get along with each other, when they can listen to each other again. That’s the faith I have. I know that feeling exists. But right now, we’re in a time where there are too many elements who are trying to disrupt that, and I think that we need to get more distance from the era of COVID before people are going to consider trusting the government again.

You wrote in the book that in the days and weeks following the October 7 attack on Israel, the inability on the part of many to empathize with the Israeli victims of Hamas revealed a moral bankruptcy, not just on campuses, but on the part of the progressive left. How would you view the campus protests, both as you were writing and since then, overall?

I went down to the protests in Toronto just to talk to people and see what was going on. I had some family members who were involved in the protests, and I found, overwhelmingly, that the people who were protesting were protesting against what was happening in Gaza; they didn’t want to see the demise of the State of Israel. There were very small groups of people who were co-opting and exploiting the moment with really extreme rhetoric and painting the entire movement with those colours. But the young people I encountered, the ones I met, were reasonably looking for a way to influence what was going on.

Where I objected to them, and I didn’t write this in the book, but when I would have conversations with them, I would say there are more innocent people dying in Sudan right now, being killed in a war there that we’re ignoring. And I watched the worst humanitarian crisis, probably in my memory, in Yemen over the past ten years, and so why is this one the one you want to take on? You want to divest from weapons sales? Canada provided four billion dollars’ worth of armoured vehicles to Saudi Arabia and nobody protested. Nobody got up on university campuses and complained about that. If you have an issue with weapons being sold to Israel, then make that more across the board.

You wrote that “change requires radicals, people who are willing to go too far in order to demonstrate obvious facts.” How would you apply that to the current context?

I think if you’re a radical activist, it’s in your blood. As I point out in the book, it wasn’t in mine. I just didn’t measure up.

I think in politics in general [radicalism] moves the needle. It moves people a bit more toward an understanding. On the Danforth in Toronto, there are these signs everywhere saying that public transportation must be free for everyone. And when I see them, I think, Well, that’s ridiculous. We’re never going to have that. But then I started thinking, Well, I guess it should be more affordable to those who are struggling. It’s really expensive.

And I saw that in my own family. My family moved from being, in the 1950s, pretty conservative people to becoming kind of moderate people, because they were getting a range of ideas that were pushing and pulling them in different directions. My mother would say, “Well, I don’t believe in all this women’s lib stuff, but I sure think women should be paid the same amount for the same work.” But she had not held that view just a few years earlier, when she told me that men have to be paid more than women because they take care of women. And I thought that was fascinating, I thought if my mother can change her tune, we all can.

What’s your strategy when it comes to talking to people at Trump events or at the Freedom Convoy or from similar worlds? Do you question them? Do you challenge them? How do you both get to the root of where they’re coming from and at the same time not feel yourself complicit or pretending that you share their beliefs?

What I’ve been doing as I travel the country with this book is asking people what sources of media they have because I want to know where they get their news, what information they get, so when they say they blame Trudeau for everything, I know where that comes from. People have so little access to reliable media. They tell me that they get their news from Facebook or from X, which is now really common, because they had a newspaper that was closed down. They had a radio show that used to have more news on it. It doesn’t exist anymore. It’s down to the CBC, which we’re told is going to be dismantled.

The danger isn’t that you start to believe lies. The danger is that you can’t tell what’s true or not anymore, and you don’t know what’s fact and what’s false. That’s where I think I see the greatest dangers as I talk to people across the country right now: they don’t know what is reliable. They don’t know what information they can trust. And when you can’t trust, you can’t have social cohesion.

We have to trust each other. We have to agree on what’s true, on what’s fact. We have to agree on that to some degree in order to have trust and have a society. When I talk to them, I want to know where they’re coming from, what they know, and how they know it. If they come into my events, they are generally aware that there’s something wrong that they want to fix, but they don’t know where to go to get that fixed. They just know that they’re not getting the truth. So they just don’t believe in anything anymore. And that’s the really scary place we are right now.

My first conversation with Off took place weeks before the US election, on November 5. Off seemed, on the whole, cautiously optimistic about the outcome. She spoke repeatedly about Kamala Harris’s overt commitment to the liberal democratic norms she herself so treasures, especially Harris’s pledge to govern for everyone, no matter who they voted for, and to apply the laws evenly to all Americans. I spent election night at Howard University, in Washington, DC, reporting for the Toronto Star from what was supposed to be Harris’s victory party. I watched in real time as that same optimism drained from Harris’s closest supporters as the reality of a relatively comfortable Trump win settled in. Days after I returned, I spoke to Off by phone again, this time from Moncton, New Brunswick, where she was attending an event in honour of the book. When I asked her how she was feeling about the election she told me that she was struck by how deeply invested so many Americans were in not having a woman, and especially a woman of colour, win the presidency.

Carol Off: We tend to think racism is something that white people do. But white people have no monopoly on racism, despite their best efforts. There is deep racism within different ethnic communities, and so the racism of one group against another was also playing into this. So when you say, How can people of colour vote for this man who is calling immigrants vermin? Well, a lot of people of colour don’t want more immigrants to come in, just like a lot of white people don’t want them.

In Canada, we look at this through our lens of feeling that we’re superior to Americans. But Canada is the only country in the world, I believe, not to share a border with a refugee-producing region or a migrant-producing region. So we have never had hundreds of thousands of people pour over our borders looking for refuge, as the rest of the world has. A million and a half people walked into Germany, and in a year, they absorbed that and continued to exist. Europe is just overwhelmed with people, with migrants. The Mediterranean Sea is probably the largest graveyard in the world, full of people who didn’t make it. And the United States had a crisis like that at their border. There were tens of thousands of people coming over the border or trying to. If Canada had that for five minutes, we would stop being this great hope for the universe. We would lose our reputation very fast if we were faced with the spectre of what Americans are faced with.

What do you think of the way the immigration debate has changed already in Canada?

It’s interesting. Pierre Poilievre tries to avoid demonizing immigrants the way Donald Trump did. But Donald Trump didn’t start off demonizing immigrants. He started off demonizing Muslims and other different groups of people. He was very selective at the beginning. In the end, they were all vermin, ready to poison the blood of solid Americans. Poilievre has avoided that language. But, and this is what I try to point out in the book, the way he’s done it is through this wokeism idea. Pierre Poilievre is not against the other. He’s against wokeism. But if you try to take apart what he means by wokeism, it is the other. It’s the people who he doesn’t believe should have the same rights and privileges as other people do.

If you’ve seen the recent ads he’s had, which depict him and his wife walking through beautiful hills, it’s like The Sound of Music. He’s in this beautiful country. But then it turns to these dark images of people on the street, these sort of “denizens of the dark side.” They’re not even described. He doesn’t say these immigrants or street people, or poor people or drug dealers or whatever. He doesn’t say that. He says, The woke agenda is destroying the Canada that we love. The woke agenda has to be eliminated. And these are words over top of these images. And so what is the woke agenda? When he speaks of the woke radicals, of the woke mob, what does that mean? It means, I’m not racist. I’m not discriminating against anyone. I’m just against wokeism.

The latest thing is, he’s got a petition out to stop the woke agenda that would have us eating bugs. There’s no word of a lie, a petition. A factory in London, Ontario, opened. It was developing crickets to make into food that goes into dog food or pet food. And they also employ about one hundred and fifty people. It’s just a business, right? But they got a little bit of government money as a start-up. And so now he’s [arguing] that the woke agenda of the Trudeau government is going to have us eat bugs, and have our children eat bugs. So we have to sign this petition and donate here, at this button, in order to help him prevent Trudeau from hoisting bug food on you.

It’s just this creeping idea that there are these foreign ideas, these weird things, that are being foisted on us and you can’t define it. He won’t define it. He’s just going to call it wokeism and that’s what we’re stuck with.

I suspect that if you were to have a coffee off the record with the Conservative people designing the stop bugs for wokeism petition and that kind of thing, their language would probably be not dissimilar from someone who runs analytics for a big newspaper or a big media company. They would say, Well, the data shows us we get a reaction from this. We’ll get engagement from this. We can harvest emails and phone numbers and contacts from this. Did you think much, as you were writing the book, about the extent to which analytics now determines content, not just for journalists, but for politicians? About, in other words, the incentive structures of the information infrastructure we’re living in?

I think those things, the reaction and the engagement, have always been part of politics. They’ve always tried to find those button-pushing things, but I think that they’ve got far more scientific tools to deal with it now. They’ve got better technology and they’ve got this incredible tool, which is social media, to push these things. Engagement also means connecting emotionally, right?

I covered politics in both Quebec and Ottawa. I covered one referendum campaign in Quebec and a lot of politics elsewhere for about eight or nine years, long before social media. There was this one extraordinary moment, this scene where there was a federalist politician in Quebec who was campaigning for the “no” side. He was in a seniors’ facility, talking to them about what was going to happen if Quebec separated from Canada, how they would lose their pensions, how they would be poor and hungry. And he looks down, and there’s a woman in the front row, and she’s peeling an orange, and she’s listening, and he says, “And you’ll never have an orange again.” And she froze. She looked at her orange, and she thought and contemplated this idea that if she voted for separatism, she’d never eat another orange.

Pierre Poilievre has said that there’s going to be economic nuclear winter if the Trudeau government prevails. Not only will people the freeze in the dark, they will be malnourished. I’m old enough to remember when nuclear winter was just the most frightening thought, and it had nothing to do with economics. But he uses that language, and no one calls him on that. I’m working at this and thinking, Come on, journalism, where are you, that you’re not pulling this apart, when he’s saying about how we’re going to freeze in the dark, and poor people, older people, senior citizens won’t have enough nutrition or heat to warm their bones, and they’re going to be living in nuclear winter? I mean, for God’s sakes, fear mongering of that nature shows us, I think, where this man is going.

What would it mean to effectively call him on something like that, as a journalist?

Well, you can, but it doesn’t make any difference, right? Because one of the key things he’s doing, which, again, demagogues do, is to demonize journalism, because you can’t have a counter-narrative going. You can’t have any independent media challenging these things. Otherwise you can’t get away with them, right? But the media in this country is already so weakened. We have news deserts across the country, very little national media, and everyone who is covering things is covering eight stories at the same time. You just get the story out and you can’t then go back and rationally say how ridiculous this is.

I covered the Harper Conservatives, and they were very good at this kind of Whac-A-Mole. They would say one outrageous thing, John Baird would say it or Jason Kenney would say something, and you’d jump on it in an interview. But by then they’ve already scurried down the trail and popped up someplace else with another outrageous thing. So even if we had a robust media, it’s hard to stay ahead of these kinds of remarks and people. But I think in the Harper era there was still a lot of skepticism and a lot of belief that journalists were doing the right thing, that we were doing our jobs. Now this effort to demonize journalism, and even the truth itself, is having an effect.

Did Trump’s election change the way you think about anything in the book?

The way I felt about the book changed so many times. Writing the book, for two and a half years, I felt despair. I thought, I hope I’m wrong about these things. I hope this isn’t real. And I began a number of times to think that I was going to be overtaken by events, events that were going to completely dismiss and discredit the MAGA movement, and the book just wouldn’t be as relevant. You’d have solid opposition that was overtaking people and winning them back to a kind of a rational side of things. And then I also had the fear that I’d be overtaken by a war, by actual violence breaking out, that the idea of trying to restart a conversation was a Pollyanna idea given that there would be people at each other’s throats. So by the time the book landed in the beginning of September, I was pleasantly surprised that the worst of it hadn’t happened, and that there was this positive possibility of change, that Kamala Harris’s politics of hope, this rational argument to return to a government and to a democracy that took care of its people, even if they didn’t vote for you, even if they didn’t wear your hat, that it was going to go back to the rule of law and not someone’s whim. And I thought, well, this is great. I felt like I was right about what the dangers were but now I’m seeing them put to rest. And then I find out in November that things are actually worse than I thought they were.

Will there be an addendum for the paperback?

There will have to be, right? I don’t know what it would be. Who knows where things would be by then? I probably will end up doing some kind of a limited podcast, and maybe a Substack or something dealing with new words that are coming out. I believe that the word of 2025 will be the word “immigrant.” And if I was going to do another sequel, the number one word would be “immigrant.” We’ve thought about “immigrant” as being something positive. Everybody in Canada, except Indigenous people, comes from an immigrant background. We’ve looked at it as multiculturalism, as diversity, as newcomers, as state builders. That’s how immigration has been seen. Now it is going to be a dirty word. It’s going to be “migrants” and “aliens” and “the other” and “The Great Replacement” and “vermin” and all these things. It will become something that’s negative. So if I were to do, not so much an addendum, but if I was to do it again, I think immigrants would be a keyword in the book.

Anything you want to mention that we haven’t talked about in either of our chats?

I’m sitting here in Moncton on a bleak day outside, the Canadian flag completely limp on a building out there. I don’t know. I just hope that Canadians are stronger, they have stronger minds and less prejudice in their hearts. That’s all I can hope for. And I hope that maybe, and this is a faint hope, but I hope that whatever analytics the Conservatives have, at some point, they find that people are moving away from this and that they don’t want to live in a world of rancour and anger and loathing, that it’s self-destructive. Maybe there’s hope that they start to realize that all of this might be true according to their analytics, but no good can come from it.

How optimistic are you that that will happen?

I think that we’ll go through the cycle and come out the other side. I think we are social animals, and we, in the end, need to get along in order to get things done. Climate change, of course, looms over everything and is a crisis that will test us to the nth degree. And it may be that it means that we have to pull together in ways we never have before and start to work out our differences. I don’t think, right now, that we’re that polarized. I think there’s just these loud voices on both the right and the left, extremely loud, bullying voices that tolerate no criticism, no other voice. I think the vast majority of us are in between feeling frustrated and looking for leadership. And I think what’s missing right now is political leadership, someone who would have the courage to put their head above the parapet and see how we might get out of this, and how they might lead us out of this. But we’re lacking the leadership we need in order to get out of this polarized, bullying, left/right divide, and start finding the common ground among the vast majority of people who want to get along.