Allow me to preface this retelling by saying that I neither regret nor relish how things have unfolded. Whether it’s because I’ve gradually been dulled down to the cold naked facts by my endless and sequential retellings—something like a diary being repurposed into a textbook—or if I’ve simply always been this way is difficult to say.

The manner of my demise is of little interest, besides serving as our jumping off point. In the spring of 1935, I left home at the age of seventeen, inspired by the many adventure tales of my youth, and promptly died eleven days later. On the night of my flight, I played checkers with my kid brother Claude, our parents having long gone to bed. He—Claude—was the only other person in the world who was aware of my planned secretive departure. Knowing that my brother wished for me not to leave so soon, I wagered that if he beat me, we’d play another game. When it became abundantly clear that he stood no chance of victory, a dark and brooding Claude brought his tiny fists down onto the gameboard in a tantrum. The red and black wooden pieces clattered to the floor at our feet, and I bid my dear brother farewell.

It’s not worth ruminating on what could’ve happened had I stayed. I was timid and friendless and thought that drastic measures were needed to alter my position in life. Would I ride the rails in stoic contemplation? Join in with a rowdy band of ne’er-do-wells? Team up with some daring gang of bank robbers? Spend nights carousing in transient motels? Or sleeping under bridges? Singing our hobo songs around a raging campfire in red-faced boisterous revelry? These were my daydreams as I sat at my booth inside a lone roadside diner to escape the pouring rain, brainlessly skimming through the penny-saver menu and jingling the change in the palm of my hand, deciding on what would become my final meal. My beans on toast was only halfway eaten when the waitress, yawning and heading into the final stretch of a triple-shift, discovered me.

<>

With the absence of any proper identification, my body was relinquished from the county morgue to a local funeral parlour, where an arsenic-based embalming fluid was administered by the owner in anticipation that a next of kin might turn up. In the meantime, my dried remains were kept fully-clothed in the back storage room, where over the course of my tenure I became something of an honorary town citizen. On Halloween, my corpse was fitted into a cowboy outfit and displayed in the parlour lobby during the year’s haunted house festivities. This proved to be a hit among the attendees, with several notable community leaders posing next to my mummy for photos, which were featured prominently in the popular town newsletter.

Ever the shrewd businessman and strange inventive mind, the funeral parlour owner went about redecorating the back storage room in the Old West style, adding wagon wheels and cactus plants, installing a set of swinging saloon doors at the threshold. Sitting at the kitchen table with a yellow legal pad, the owner and his enterprising schoolteacher wife spent a pleasant evening together dreaming up my fictional biography:

¨ JASPER GUNN! THE MUMMY BANDIT! ¨

As a member of the notorious Heartworm Gang, Jasper Gunn along with his Partners-in-Crime—— ‘Lying’ Lyle Lopez, Buster ‘Big Boy’ Bagsworth, & The Heartworm Brothers—were the scourge of The American Old West! Following a lifetime of Crime & Drink, he met his bitter end when a Quarrel over Stolen Loot turned Deadly! Jasper was gunned down by his Compadres in Cold Blood! The Dry Volcanic Sands of the Great Altar Peaks Transformed this Sorry Sinful Soul into a Mummy! Where the Outlaw lay Dead & Buried in the Desert for over 100 Years! Look Closely Children and Let this Be a Lesson for you that:

¨ CRIME DOESN’T PAY!! ¨

Their effort proved to be successful enough that the couple, who had never travelled and were nearing retirement, bought a small concession trailer and took the exhibit out on tour.

In 1937, The Mummy Bandit’s Crime Doesn’t Pay! touring exhibit passed within eight miles of my family home. An advertisement was placed in our local paper, which led to something of a minor frenzy among the children of our small Canadian township. Regretfully, my brother—probably the only person who might’ve been able to look past my cowboy getup and glue-on horseshoe moustache and ghastly wax-like exterior—was being punished at home for stealing cigarettes. The exhibit became the main discussion topic amongst his peers and Claude, scowling and sour about missing it, chewed his lower lip waiting patiently for the subject to change.

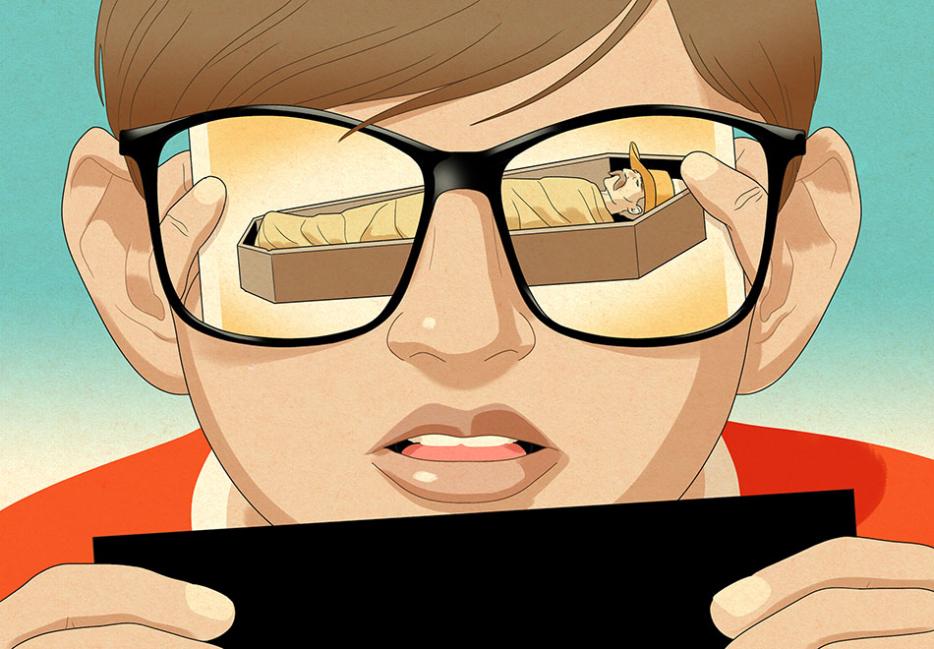

During the spring of the following year, a bespectacled ten-year-old named Harold Boyd was traveling with his family across Nevada to the Grand Canyon when they stopped to see the exhibit. By then, the exhibitor’s wife had penned five separate three-page adventures featuring Jasper Gunn and his unsavory crew, sold for a penny apiece. Harold paid a nickel for the lot, which also included a bonus illustrated postcard of myself as the mummy cowboy mounted upright in my coffin. That night, Harold sat by the campfire admiring his grotesque new postcard; the crackling fire reflected from his thick circular eyeglass lenses like a pair of twin lighthouses as he read through the stories.

Eleven years later, after Harold joined Atomic Color-Comics as a junior illustrator, he came up with a new character inspired by the gunned-down Old West bandit that he’d visited as a boy. Working late one evening, Harold redrew my shrivelled remains in the cloth-wrapped style of the Egyptian mummy. What follows is an early character biography first recorded into the personal sketchbook of Harold Boyd.

Notes & Ideas 9 – 27 – 49

Duke Alvarez, feared gunslinger of the Old West, was captured by the nefarious frontier scientist & occultist Professor Coltrane Von Tutt during a bounty hunting mission-gone-wrong. The weird-and-vile Doctor administered a sleeping-serum of his own creation, then wrapped our helpless hero in bandages, while reciting an unearthly evil curse, and buried him deep below the desert sands, where he remained for over 100 years! When lightning struck the very spot where this wicked deed had been done, The Mummy Outlaw was awoken! The wrongdoers of today will soon fear his particular brand of Old West Justice!

On February 15th 1950, Atomic Color-Comics published Duke Alvarez: American Mummy Outlaw #1. With the help of Wally Pepper, Harold’s desk mate and frequent collaborator, the pair went to work fleshing out the arid crime-ridden desert metropolis of Pinkstone City, introducing villains like Mister Mirage, Lyle the Human Reptile, Giant Ron, and the irradiated Skelton Twins. Within the first two years of publication, Duke Alvarez: American Mummy Outlaw gained a nationwide circulation of nearly 300,000 readers, making it the highest-selling title in the company’s history.

On Thanksgiving Day 1953, The “Original” Mummy Bandit! touring exhibit hit a patch of black ice while travelling through rural Kentucky and collided with a hemlock tree. The cab of the pickup exploded on impact, killing the two elderly occupants instantly. The exhibit trailer flipped end-over-end, then ripped in half, scattering flyers and lead cowboy figurines across the burning wreckage. The first responding officer on scene found the two halves of the exhibit trailer engulfed in flames. The officer’s shadow swayed in the dancing flamelight, as he bent down over my smoky remains searching for a pulse, attending to what he presumed to be the third victim.

Beginning in the early 1960s, Starbrite Pictures optioned the television rights for Duke Alvarez: American Mummy Outlaw and started putting pitches together. After nearly a decade of misfires and false starts, Duke Alvarez premiered during the fall television lineup of 1969. The series was an instant hit, leading to an avalanche of tie-in advertising and merchandise, and transformed the show’s lead—Charles Lance—into a household name seemingly overnight.

The early success of the series led to notable media writeups about virtually every aspect of the show’s production. It’s worth noting that nearly every article written during this period attributed sole credit to Harold Boyd. Of a total of twenty-seven pieces published during 1969, Wally Pepper’s name appeared in print exactly three times, one being misattributed to a “Willy Pooper.” Maguire Magazine published an investigative piece titled “The Macabre Origins of Duke Alvarez!” in which the Jasper Gunn Mummy was for the first time widely credited for serving as the character’s early inspiration. This led to the unsubstantiated rumour that my mummy could be spotted briefly during a large crowd scene in the second season’s “Demons of The Diamond” baseball-themed episode. Though by then, my corpse had mostly vanished from the public eye, after being sold discreetly to a private collector by a black-market art and antiquities dealer from Jonesboro, Arkansas.

In 1970, my nephew—whom my brother named Phil LaFontaine in my memory—was given a checkers set, a Duke Alvarez action figure, and a Lyle the Human Reptile action figure for his seventh birthday. That evening, father-and-son lay belly-down on the living room carpet with Claude playing as Lyle and the birthday boy as Duke. Lyle the Human Reptile had stolen Duke’s signature Stetson and set of meteorite-forged revolvers, then fled to his fortified pillow hideout perched on the sofa. In a moment of sly genius, Duke gained entry by concealing himself as one of Lyle’s ghostly henchmen using a rubber band and a piece of white tissue as his disguise. During their subsequent fistfight high above the fortress, Duke delivered the decisive headbutt that sent Lyle plunging to his death off the sofa back.

On Christmas Eve 1971, Wally Pepper was airlifted by helicopter to the Trauma Center at Utah Valley Hospital following a severe ski accident. Eyewitnesses would recall spotting the novice Pepper descending a hazardous undesignated portion of trail at a rapid rate of speed, before subsequently striking an outcropping of rock. A string of Christmas lights hung above his hospital bed as he lay in a medically induced coma. Speaking candidly with family members not long after the accident, Wally’s neurosurgical team insisted it was unlikely that he would ever regain significant cognitive function. A post-surgical infection would later take his arm. The last page of Duke Alvarez: American Mummy Outlaw #252, published that February, featured the roster of Atomic Color-Comics characters hoisting a banner that read:

GET WELL WALLY!

During the early part of the 1970s, Harold Boyd began the prolonged process of distancing himself from the title that had defined his career. A slowly developing tremor in his sketching hand, in addition to the loss of his closest creative collaborator, proved to be the main catalysts in his decision-making. Leading up to Duke Alvarez’s third season TV finale, Harold Boyd and Atomic Color-Comics quietly negotiated a contract which signed away character ownership rights in exchange for a robust cash settlement. In the fall of that year, Harold left Manhattan for rural Connecticut, purchasing a turn-of-the-century Tudor house on fifty acres.

A combination of declining ratings, plus a studio fire that destroyed the majority of the show’s props and set pieces, culminated in Duke Alvarez’s cancelation after four seasons in 1973. Apart from a few TV commercials and print advertisements and Bandito Mummificato! (the 1976 unauthorised Italian TV remake), the character wouldn’t appear in live-action again for another four decades.

Duke Alvarez star Charles Lance, who’d squandered the vast majority of the small television fortune he’d seemingly made by the time the series ended, was also the only actor from the primary cast not offered a voice role in the upcoming Saturday morning cartoon. In fact, the decision to recast Duke had been a forgone conclusion heading into the unproduced fifth season. This came as no surprise to anyone from the original production, who were already well-aware of Charles’ erratic onset behaviour and a slew of unsettling personal proclivities. Though yet to be proven, it was also widely assumed within industry circles that Charles had at least partially played a role in the studio fire that led to Duke Alvarez’s cancelation after discovering that he was to be replaced.

In 1979, Illinois State Police raided a storage facility in Cicero, uncovering a cache of stolen art and pop memorabilia valued at nearly a quarter of a million dollars. A twenty-two-year-old rookie trooper ducked behind what he presumed to be a pilfered zombie movie prop and tried lifting it so as to frighten his fellow officers when he unwittingly severed my left arm at the wrist, exposing the skeleton. By then my corpse, which had been treated using a type of glow-in-the-dark lacquer, weighed just under 50 pounds. My glowing remains were transported by ambulance to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office, where it was later determined, with the help of an inventory log seized during a simultaneous raid, that they belonged to the missing Jasper Gunn Mummy.

Beginning in 1981, the Pepper family started circulating a self-published memoir allegedly written by Wally from his hospital bed. The slim pamphlet-like volume, titled The Mummy in Me: A Strange & Shocking Tale of One Man’s Fight for Truth in Tragedy, made damning allegations against Harold Boyd. Namely, that the character of Duke Alvarez had been stolen outright, using threats of future violence to buy his silence. A further accusation that foul play may have been a factor in his ski “accident” was excised late in the editing process. Though it was widely presumed that Wally had remained in a vegetative state for the better part of a decade, family members insisted that he had slowly and painstakingly dictated his autobiography through a series of slight lip and pinky movements over a period of more than five years. While the initial print run was limited to only 900 copies, a small but vocal subset of readers became a regular sight at comic shops and fan conventions, waving their wrinkled and heavily underlined softcovers at a mostly disinterested and unenlightened public.

By the 1980s, Atomic Color-Comics—retitled AC Comics Entertainment, Inc.—had fallen into financial turmoil. In an effort to cut costs, mass layoffs were conducted across the board and more than fifty percent of AC Comics’ ongoing titles were canceled. Though Duke Alvarez: American Mummy Outlaw survived relatively unscathed, subsequent issues were produced at a fraction of the cost. Longstanding readers criticized what appeared to be an utter lack of copyediting, sloppy draftsmanship, and a growing number of continuity errors. More infuriating still, a change in paper stock resulted in pages that seemingly deteriorated at the slightest touch, a run of comics that notoriously came to be known as “the toilet paper issues.”

Among a certain contingent of fans, blame for the steepening decline in quality rested solely on Harold Boyd. Baseless claims referencing his seemingly infinite wealth, garish lifestyle, and alleged veiled influence over every aspect of AC Comics’ business interests ran rampant in his absence. In 1986, an anonymous package containing the shredded bits of an extensive Duke Alvarez: American Mummy Outlaw comic book collection, along with an undetonated and poorly constructed improvised explosive device, was delivered to Harold Boyd’s doorstep; the perpetrator was later identified as a thirteen-year-old resident of Lake Harbor City, New Jersey.

My nephew Phil LaFontaine arrived at the 1988 King City Toyland Collectors Showcase with one goal in mind: to track down a rare “blue-headed” Lyle the Human Reptile, just like the one he’d owned as a boy. An exceedingly small number of these figures had been produced, the result of a manufacturing error, in which the normally scaly-red reptilian head was erroneously molded in blue. The typically sluggish Phil, outfitted from head to toe in the style of Professor Coltrane Von Tutt, bounded out onto the convention floor with dramatic flair, flipping his homemade purple cape vigorously from side to side. His intel had confirmed that a vendor would be selling a pristine blue Lyle the Human Reptile still packaged on its original card-back, but failed to mention the price being nearly triple what he’d been anticipating. A desperate phone call home to father yielded few results and Phil, sweating with his spray-painted golden mask tilted up, empty eyeholes facing the ceiling, staggered among the rows of toys, clutching his consolatory hotdog and dripping yellow mustard onto his aluminum foil ray-gun and plastic holster. On his way back to the canteen for one of those soft pretzels, Phil saw that the Jasper Gunn Mummy was also being exhibited, accompanied by a display of antique cowboy toys. Approaching so close that he was pressing against the velvet rope, so close that they—he and my mummy—were nearly face to face, in the split-second before the exhibitor grabbed him by the scruff of his cape, it felt like everything in room was disintegrating.

Actor Charles Lance performed in exactly three film roles during the 1980s. Two were scrapped before filming completed due to budgetary issues. The third was a semi-soft adult feature screened only in select European markets. The majority of his income came from his numerous convention appearances, which were wholeheartedly unendorsed by the likes of Starbrite Pictures and AC Comics. During the latter part of the decade, Charles tried parlaying what was left of his notoriety into rebranding himself as a burgeoning restauranteur. Collecting vast sums of cash-on-loan from some particularly disreputable business associates, Charles opened The Egyptian Tomb Lounge in Reno, Nevada, which operated for a grand total of four months before unceremoniously burning to the ground. During the ensuing chaos that followed, Charles fled the country, secretly expatriating to Europe. In 1990, he was arrested in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia while wearing a Duke Alvarez Halloween mask, following a string of high-profile bank robberies, and was sentenced to seventeen years in Leopoldov Prison.

In 1997, Harold Boyd was injured during a failed kidnapping attempt inside the basement of his home in rural Connecticut. Brothers Dwayne and Hughie Huggie, lifelong Duke Alvarez fans and radical self-proclaimed Wally Pepper devotees, had been living uncomfortably out of Dwayne’s pickup truck while stalking Harold Boyd during the preceding two weeks. On the evening of the home invasion, the brothers—wearing ski masks and matching black turtlenecks—snorted a cocktail of prescription stimulants, then slipped into the house through a backyard patio door; floorboards creaking beneath their bulky frames as they quietly tiptoed from room to room. The sixty-eight-year-old Harold Boyd was lifting weights inside his modest home gym when the brothers descended the basement steps. He had taken up weightlifting just prior to leaving New York City on the recommendation of his physician as a way of curbing the impact of his tremor. The moonlight from the upstairs kitchen skylight twinkled off their aluminum baseball bats, as they craned their necks down the empty hall. During the years following the mail bomb threat, Harold had also begun an intensive self-defence training regimen partly as a way of waylaying his debilitating state of constant paranoia. It’s possible that at the age of sixty-eight, Harold Boyd was in the best shape of his life. Crab-walking with their baseball bats hoisted above their heads in matching tactical attack positions, the Huggie brothers had made it about halfway down the hallway when the basement gym door suddenly swung open.

During a radio interview on Inner Voices with host Amelia Goersch in 2001, filmmaker Gabrielle Baradino spoke briefly about her interest in potentially adapting Duke Alvarez for the big screen. What follows is a partial transcript from their hour-long conversation:

AG: Does the Pepper trial influence your decision-making at all?

GB: I mean, I’d like to sit here and say, “no, it’s not a factor,” but honestly who knows? In terms of production, I suppose, that’s a different story.

AG: In terms of production? Meaning the industry might not see it as being the ideal time to tell this particular story?

GB: Mhmm. Yes. Exactly. But I try not to think about things like that. It’s... not my area of expertise. My interest is the character. That stuff about the Gunn Mummy fascinates me though. Did you read that article that Maguire put out last month?

AG: For our listeners, The Jasper Gunn Mummy is a sideshow attraction which the character of Duke Alvarez is said to have been based upon. The article, published in the July issue of Maguire Magazine, questions whether the bandit Jasper Gunn ever existed in the first place.

GB: I’d like to think he did though, don’t you? If not, then who’s been stuck in that display the whole time? That option horrifies me.

AG: Maybe there’s a film in there somewhere.

GB: [laughs] Maybe. After everything I’ve heard about the Pepper family, it wouldn’t surprise me if they started carting poor Wally around on display. [laughs] No, I shouldn’t joke about something like that. I don’t know. Maybe I’ll make a film about the trial.

In September 2014, CNT Evening News Nightly aired a segment about how researchers at Keirstead College Teaching Hospital had begun an investigation into the identity of the Jasper Gunn Mummy. On the same evening, my brother Claude was wheeled into Marble-Brooke Senior Living’s General-Purpose Room in anticipation of his son’s weekly visit. Examinations of the mummy’s hands and panoramic X-rays of the jawbone estimated that the age-at-death was somewhere between sixteen and twenty. In the meantime, Claude scrutinized the room, alternately winking and scowling at the residents and care workers within eyeshot before diligently watching the door. The news segment showed my corpse being wheeled down a hallway on a gurney before subsequently sliding into an MRI. Had it really only been a week since Phil’s last visit? A member of the investigative team explained that there was a high probability that the Gunn Mummy’s body had been stolen prior to being displayed. Gunn. Where had he heard that name before? Glancing uneasily from the doorway down at his wristwatch, Claude recoiled at the sight of his bare arm gone into a state of wax-like semi-decay, hand reattached at the wrist by wire, with portions of the shiny-white bone exposed through shrivelled, faintly glowing paper-thin skin. These types of hallucinations were becoming more common. An undated black-and-white photograph of The Mummy Bandit flashed on screen, along with footage of a digitally enhanced Duke Alvarez fending off a gang of ten-foot-tall slime-people in a scene from the upcoming feature film. Unsettling confusion lines crept over my brother’s aging face; a blue lizard-man and an Old West style mummy—like life-sized versions of Phil’s boyhood toys—were playing checkers next to the television. A research scientist on screen said that they planned to use genetic testing in the hope of potentially identifying a surviving relative. The blue lizard-man, who under closer scrutiny, actually looked more like a blue lizard-boy, brought his slimy fists down onto the gameboard in a lizard-tantrum. There was a closeup shot of my face on screen as the red and black pieces sprung to life. Twenty-four pieces. Each falling in their own particular way. Like countless retellings, slightly different, but all eventually heading in the exact same direction. Still, sometimes it feels like that if I focus, that if I can string together the perfect combination of words and tell it just right, it’s like everything is finally ending and I bid my dear brother farewell, before the pieces strike! the floor.