The mainstream notion of an archive generally consists of documents—photographs, letters, publications. But an archive, a site of history and inheritance, can be much more expansive. An archive can be a piece of fabric, an oral story, even a body. Many recent publications have explored a broader notion of archive from the perspective of people whose stories and lives are sparsely documented, or entirely erased, from the Western forms of historical annals. From Saidiya Hartmann’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments to Jenn Shapland’s My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, and even fiction like Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s Sabrina & Corina, what constitutes an archive is more imaginative than the narrow confines of paper and ink.

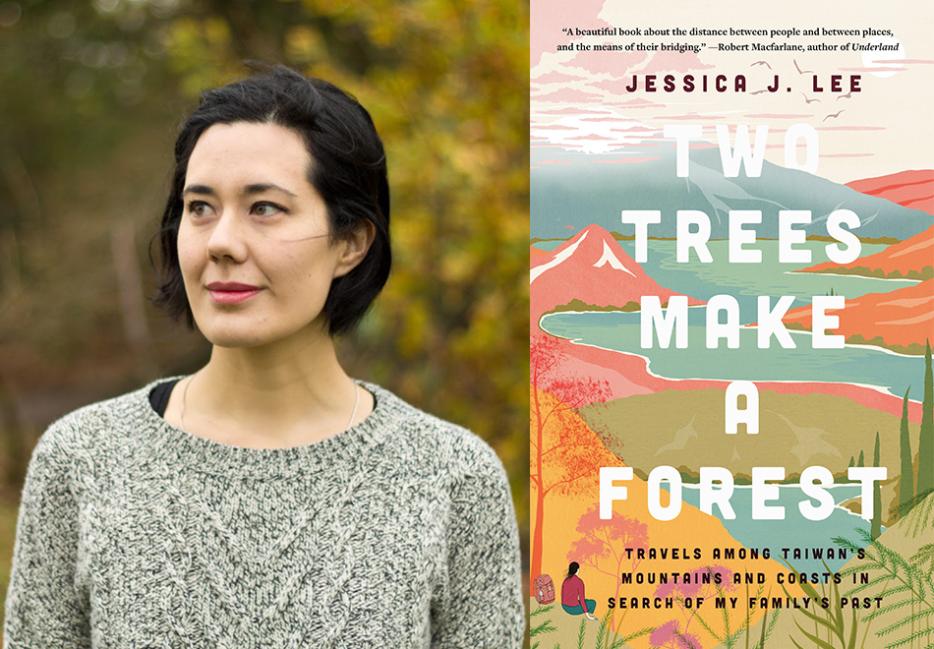

Jessica J. Lee’s sophomore memoir, Two Trees Make a Forest (Hamish Hamilton, 2020), engages with this theme of archive in its own far-reaching way. A memoir of family, landscape, and natural history, the book begins with Lee coming across some letters written by her grandfather before he passed away from Alzheimer’s. Lee’s mother is Taiwanese, but Lee grew up in Canada. She returns to Taiwan with her mother, to get to know her family and herself through getting to know the land. There she explores the landscape of the island on foot and on bicycle, from mountains to coast, all the while navigating the things that are lost and found in translation: translation of her grandfather’s letters, of her mother’s body language and her own, of her grandmother’s stories, and of the imperialist and colonialist mapping of Taiwan and its flora and fauna. “The story of a place—lithic, living, and forgotten—can be found in maps and what they include or leave out,” Lee writes. When Chinese, and later western European, imperialists began mapping Taiwan in the 16th century, they imposed their own stories onto its landscape and people. Taiwan, Lee writes, resists mapping, as its interior landscape is difficult to access and traverse. “Today, maps continue to show Taiwan tangled in mystery,” Lee writes. As she journeys into this mystery, she learns about the international and interpersonal conflict, the language and lack thereof, and the inherited narratives that shape humans and landscapes alike.

“The gaps that bind us span more than the distances between words,” writes Lee. “Nature stitches a seam between our anthropogenic divides.” I spoke with Lee over Skype about family, history, and the meaning of place.

Sarah Neilson: So much of the narrative of Two Trees Make a Forest is about gaps—between fault lines, mountains, languages, diaspora, and the gaps within families. In what ways are those distances limiting, and in what ways are they sites of possibility?

Jessica J. Lee: The issue of gaps was the central thing for me at the very beginning of working on the book—it was probably the first theme that really emerged. In fact, the original title of the book was centered on the theme of gaps. So it was really apparent to me, because I came to the story with the issue of the primary language gap, and then that gap in time and connection to Taiwan. It became a space, as you said, of possibility, a space I could occupy to just ask questions in a more spacious way than I could if I felt like I had to know everything. It allowed me to not know things, and therefore to write that learning into the book, to ask questions of my grandparents' stories and of history. I think if I was trying to write a book where I wanted to take a position of authority, it wouldn't work. It's very much about not being an authority, about trying to get to know a place, about trying to bring the language that I know best, which is that of landscape, into the gaps that were there to offer some connection.

I wanted to ask you about that natural landscape language—you divide the book into four sections, roughly translated as “Island,” “Mountain,” “Water or river,” and the last section is “lin,” which has two translations: forest, or a group of like persons. What are the metaphorical and literal meanings behind dividing the book into these natural phenomena?

It was partly a structural thing. I didn't start out with those divisions, but the more I sat with the story, it really helped me to frame what was already a very fragmentary story. It was always going to be a challenge to piece it together, because the key text I was working with, which was my grandfather's life story [in some of his letters], was a series of fragments. It was written when he had Alzheimer's and was developing Alzheimer's. So I think it helped me not push against but work within the limitations of a fragmentary structure.

I thought about those words a lot, because they're really basic words in Chinese—they're the first ones you learn, really. But they were also words that really shaped my experience of landscape in Taiwan. When I was learning how to read, and when I didn't know where I was, those were the kinds of words I could always read on a street sign or on a trail marker. That was really important to me to give myself some framing so that I wouldn’t feel completely adrift. Also, it was hard for me at times to figure out the right place for certain parts of the story. And that's why, at the end of the book, I turned to this idea of the forest. The forests were not the key framing idea of this book when I set out, but they very quickly became that.

I’m particularly interested in that last section because of the elegance of the image of a group of like people as a forest or grove, connected by roots and symbiotic relationships with its growth media, its place—its soil. How do you think natural landscape influences or embodies human connection? How do you think politics and its violences does the same?

The reality is, when I go into the forest, I'm always reading into it, reading personal things into it, even when I'm trying not to. I bring literature, I bring details, I bring family history, I bring that kind of knowledge with me. I feel like it's really important to acknowledge that, and to really see those things as layered, and to not assume that we can speak about landscapes as pristine or apart from us, as if that was ever possible. So much of the natural world has been shaped by us. And so it's inherently political. It's inherently cultural. For me, Taiwan was a really ideal space to think about where these things converge. There were the personal elements, there was the more intellectual interest in natural history, but also a really strong desire to understand history that I didn't understand until I really delved into it—to understand that a history of a place happens on so many levels. There's that personal experience of the place, there's the family, there's the political, and they're not distinct.

You explore the idea of mapping quite a bit, and the question of who draws what maps. So much of what is known, on a global scale, about Taiwan’s biodiversity, geology, and geography in general bears the marks of imperialism, colonization, industrialization, war. Can you talk a little about mapping your own exploration of the island? Was there anything that surprised you, while you were there in person and/or when you were researching historical documentation?

I was really confronted with the challenge of not only mapping, but getting places was in a way my big challenge in Taiwan. I didn't have a strong knowledge of Taiwan's interior in the central mountains before I set out specifically to [explore them], which in some way reflects that strange history of the flatlands being very accessible, and the mountains being very much off limits. I was really struck by the ways that you could get to know the landscape there in such a patchwork way, and feel simultaneously [it] was sort of inexhaustible as a place. I've been to huge sections of Taiwan now, a bunch of different mountain ranges. And I feel very much like I've done very little. And I would really like to keep going.

But I do think the one thing in Taiwan that is always sort of with you is that consciousness of it being colonized land and colonized space. I was always sort of hyper-conscious, also of my hybrid position as Taiwanese diaspora but also a Westerner in some sense, and as white passing. That shapes my movements through the landscape there because I'm not necessarily seen as belonging, and it shapes how you're received and what you have access to, and a whole manner of other things. I think I carried a lot of consciousness of that historical relationship of mapping and politics in the place and where I fit in a contemporary frame moving across that same landscape.

To expand on the idea of maps, in what ways are our family artifacts maps, and in what ways are our bodies maps? And how is the body not only a map, but a tool of mapping?

This book brought to mind for me the range of things that could be a map, or that could be treated as a landscape. There's my grandfather's letter, which is a more obvious one. There’s my grandmother's stories and her clothes. It's really interesting, just the other day I found a bag with a bunch of clothes that my grandmother had sewn. It's nice to still have them because I don't have a whole lot, but those are really personal things to have. When it comes to the body, the thing I think most of is actually my mother, and my observations of my mother moving in Taiwan, the way her entire comportment changed. I have basically spent my entire life thinking my mom has a terrible sense of direction, and that she doesn't really like to get out and do things on her own. When we went back to Taiwan, it was like she felt like she belonged. She felt much more comfortable. She would still get lost, but there was something in the way she moved that I think was really familiar to her and familiar to that place, but I hadn't seen it before. So just sort of getting into your body again, and feeling like your body is in the place where it belongs in some way. That familiarity, the familiarity of climate, all of those little things.

In many ways Two Trees is a story of inheritance. What do you feel you inherited while writing this book, and what new inheritance(s) do you create with it?

I think the book gave me the connection that I had never really had to my family's past. I didn't really give it enough thought when I was growing up, and I kind of took it for granted. [The book] gave me that very direct connection to my family's legacy, and to my culture, in some sense. That was really valuable. I think the biggest thing that I took away from working on this book aside from connecting with Taiwan, and language in place, was extra time with my grandparents. I was working on this book for two or three years, and it was kind of like I was having conversations with them all the time, even though they both passed away. It was like this extra time that we had to spend together, to really think about our family, to learn about one another. It was completely one-sided—it was just me and my imagination, and these words on a page that were my grandfather's, and my own.

Did your idea of home change at all while you were writing this?

I don't know if it changed so much as grew. I think I always had a very dislocated sense of home. For me, it's a question of plurality and multiplicity. Having gotten to know Taiwan a lot better and really coming to spend a lot of time there, it added itself, I guess, to a list of possible homes and places in which I belong. I don't know if I've fully resolved that yet. It's a conversation my husband and I have every few months—should we move to Taiwan? Would we feel too far away from people back home? It's always sort of there in the back of my mind now, especially as my mom's planning to move back. And it really shifted the gravity of the world for me, in a way.

I’ve been thinking about the word solastalgia a lot lately. It’s defined as “a form of emotional or existential distress caused by environmental change... best described as the lived experience of negatively perceived environmental change.” It was coined by Glenn Albrecht in 2005 in the context of the specific feeling of loss, of homesickness, experienced under climate change. This connects back to the idea of humanity as a forest, an interdependent organism. What are the places of your life, and how do you mourn them and love them at the same time in a world that now requires both? How do love and grief that are connected to place also connect to family?

It's interesting to bring up that word, because for me, it overlaps so much with the kinds of grieving we do for people and for family, because the body is a kind of landscape and a record. And I think, when we think about the natural world, it is a record—it's a record of memories that we've had and places we've been to. And it's so much bigger than us. When I go to places in Taiwan like the coast, where you can see so much changing, or the forest near the end of the book... you can see environmental change so starkly. In this flooded forest, you can see what's possible on this planet. That, for me, is one of those kinds of spaces where it brings me out of myself and my own personal grief a little bit and reminds me how big and powerful this world is, and also how much impact we can have on it. I spent a lot of time swimming here in Germany, where I've been living. I'm a really avid winter swimmer. I swim when there's ice. And that, for me, has been a real process of record-keeping in a way. Because I feel like by returning to places again and again in the landscape, you bear witness to the thing that's changing. The past couple of years for me have been about bearing witness to receding ice. We don't have proper winter anymore. The lakes haven't frozen in years. And that's like a personal kind of devastation, but it's also something that that we need to witness and we need to document and we need to take personally. And also, how do we balance that personal narrative with not seeing ourselves as the center of the universe? I don't know. For me, returning to different places in the landscape and having that cyclical relationship to it is sort of my way of marking change and witnessing change. But yeah, it's really tough. I mean, in Taiwan, I'm always going back to the same places again, and again, sort of compulsively. I very rarely go to new places. I really like to go to the same five places, just to see if there's a slight difference. And just to see if I can get that moment back again. But that’s never possible.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.