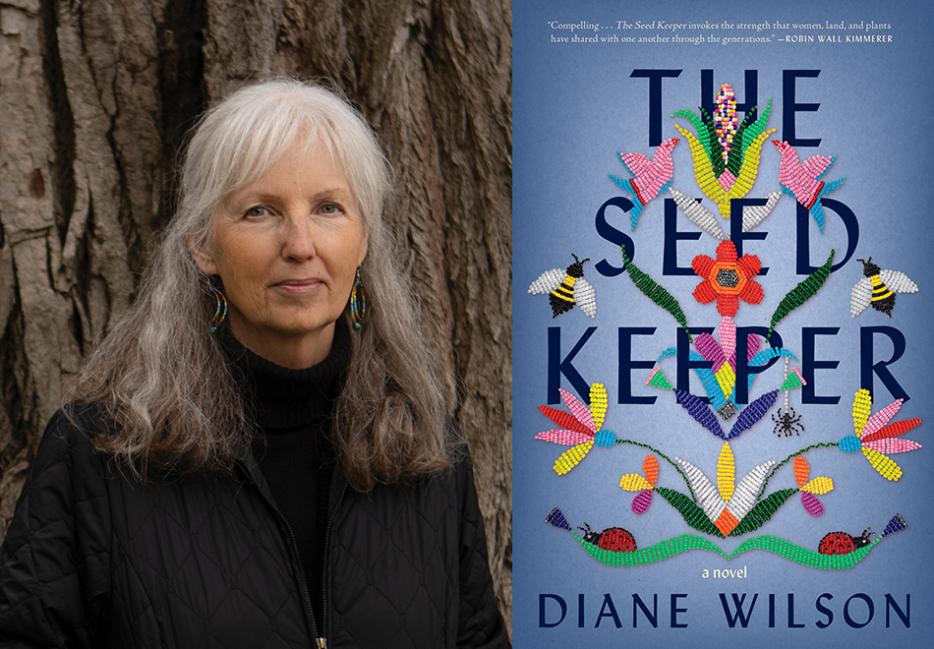

The title of Diane Wilson’s sophomore book and debut novel, The Seed Keeper (Milkweed, 2021), is already evocative on its own. Seeds are powerful both in physical and metaphorical forms. These small, dry vessels of genetic information carry profound memory, they store the energy that will allow them to grow and provide further nourishment, and their resilience across time and space is unique. It is from these dormant but indefatigable seeds that Wilson draws inspiration for her characters, novel, and life.

The Seed Keeper follows Rosalie Iron Wing, a Dakhota woman who, at the outset, doesn’t realize that seeds are a big part of her inheritance. Rosie, which she goes by, loses both of her parents and comes of age in a brutal foster system. Finding relief and escape in a summer job detasseling corn on the Meister farm, she sees John Meister, the calm and steady white man who has inherited the generations-old farm from his family, as an acceptable way not only out of a life that doesn’t appear to have much to offer her, but onto and into the land she feels drawn toward—“on a farm that once belonged to the prairie.” As the story follows Rosie’s life as a wife, mother, and, finally, seed keeper, it also tells other stories: of ever-increasing divergence from a relationship with nature (in the form of corporate agriculture), and of Rosie’s ancestors, women who carried and cared for the seeds on which they had come to be mutually dependent. The Seed Keeper is a beautiful ensemble story about family, grief, reverence, and what it means to live with, not just off, the land.

“These seeds carry our stories; they are witnesses to their own long history on this land,” Wilson writes. Her knowledge of and love for plants is palpable in her writing, as is her longtime work with nonprofits working toward Indigenous food sovereignty—she is a board member of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA). I spoke with Wilson on Zoom about agriculture and food, capitalism, memory, and what it means to come awake by fire.

Sarah Neilson: I wanted to ask you about the tension, or maybe not even tension but parallel existence, of the ideas of “wild” and “domesticated.” The two show up both literally and metaphorically, in people, animals, and plants. There’s a line where Rosalie, who is pruning in an orchard, narrates, “While my father believed that any plant not grown in the wild was nothing more than a weak cousin to its truer self, my years of caring for these trees had taught me differently.” Do you think there is a tension between these ideas of wild and domesticated? What does it mean to be or hold wildness?

Diane Wilson: The night before my book launch with All My Relations Arts, there was a night of traditional storytelling. This was actually one of the themes that came up in an old story and it has to do with that idea of wildness. These plants, these seeds, have agreed to surrender their wildness in exchange for a reciprocal relationship with human beings. That made us mutually dependent on each other; we care for the seeds, they help care for us. So it's a really interesting tension and dynamic that happens between plants that survive on their own in the wild, and then plants that have agreed to be in relationship with human beings. That’s a big theme in the book.

The storytelling event had three different storytellers. They told Lakota, Dakhota, and Ojibwe stories about how corn came as a gift. These were stories that were told with such reverence that people understood no matter when these stories were told, what generation was hearing them, that corn was a spirit being, was a sacred plant. The reason why it is so important to indigenous communities is because it really helped people survive. Because with weather and the unpredictable nature of hunting and gathering, and, in any season, as a farmer, things can go wrong. Corn was a stable plant. It was a source of food that really helped communities survive. So the reverence is there for those plans.

There’s also a difference between the way that a character like Rosalie approaches farming or gardening, and what agriculture means in a settler context. I think, the way it exists in its dominant form, even “organic” or “sustainable” farming involves more manipulation of the land than it can reasonably take over time. Do you agree with that? What are your thoughts on the meaning of the word “agriculture” and what a mutually beneficial relationship with land and plants can look like beyond that word’s confines?

I think the big question I was trying to ask, or hopefully encourage readers to ask themselves, is about this relationship with seeds. That's why the seeds opened the book reminding us of that original agreement. They gave up their wildness—this is a huge thing—and came into our lives to help us survive and support our children. That relationship began to shift when settlers moved in; they brought a very different worldview about that relationship with plants and animals and water and soil. In Dakhota, we say Mitakuye Owas’iƞ. That means we're all related. So I have to literally regard the soil; when we use the term mother earth, it's a literal relationship. Meaning, to treat that soil with the same care and respect that you treat your own mother.

So you see the shift when the settlers came, and over time, in particular, as we moved into corporate agriculture, that there was a mind shift to viewing plants, animals, soil, water, air, as commodities. It became something that could be bought and sold. Profit and loss entered into these equations that were all about relationships in life and partnerships in order for human beings to live. That's when I think we really lost sight of what that original relationship was intended to be. I think there's a part of farming, the subsistence farmers back in the day when people were taking care of their families and rotated their crops and took care of their animals, that had more in common with that Indigenous worldview. But where we've gotten to now with corporate farming, it's all about that commodity viewpoint. That's what I think is just tragic in what is considered to be agriculture today. That is really the big question of the book, is to look at how that relationship has evolved over these generations, and what does that change mean for us as human beings.

Yeah. I really loved how in the book, the corporation was named Mangenta, a not-so-subtle nod to Monsanto.

Not subtle.

Not subtle. I think a lot about capitalism and how food and land don't really mesh with capitalism, but people keep trying. I was wondering about your work with NAFSA and what it means to you to seek food sovereignty and food security outside of the capitalist framework.

Oh, it's such rewarding, beautiful, joyful work. I've worked in two nonprofit organizations over the past 15 years that are all about restoring or supporting native communities to reclaim their sovereign food systems. What I didn't realize before I started that work was how much people have been controlled over hundreds of years through food. The way food is manipulated, the way hunger is used as a tool and has been used to control native communities, and not just native people—hunger is a huge tool. At one point, earlier in my writing career, I realized that I could actually tell the history of what happened to Dakhota people in Minnesota through what happened to their food. So, in the commodity foods that native people were given once the reservation system was put in place, and really what that did to the health of native communities. Then you link that to the health crisis that many communities are facing today with diabetes, heart disease, which made people so vulnerable to this pandemic. I look at restoring these Indigenous foods to native communities as being one of the most profound ways we have of healing historical trauma, and it's a joyful way to do it. Plants are beautiful. Gardening is nurturing and restorative, and who doesn't love to share a good meal?

One of the most potent parts of the book for me was, again, something true that happened, which was that Dakhota women sewed seeds into their clothes in order to ensure that mutual survival you talked about. Can you talk about your approach to writing such an important aspect of the story not only historically, but that directly endures today?

I heard that story probably close to 18 or 20 years ago when I was participating in the Dakhota Commemorative March. That was before I really got involved in the food sovereignty work, but it made such an impact on me to think of the sacrifices those women made and their determination and commitment to making sure that those seeds survived for future generations. As I moved into doing the food sovereignty work and realized how much we owed to the women and people like them who made sure that these foods were preserved for us today so that Dakhota corn—so many of these seeds have already disappeared—but that Dakhota corn was preserved by enough families that it's now being grown out again by a local nonprofit called Dream of Wild Health. I have those Dakhota seeds to grow out in my own garden.

To me, it's all part of the same work. I can work for a nonprofit and have an impact that way. I can write books that then share it through stories that enter into people's imaginations. Then I can grow it in my own garden so that I can have that experience myself of what it means to take care of those plants. So my approach to writing that kind of historically based scene is to try to enter into the experience of it as deeply as I can. When I plant that corn in my garden, I bear in mind those women and their actions.

I was so drawn to the way you layered complex relationships between characters and complex relationships with land. For example, Rosalie and John have a very layered relationship with each other and the land where they live. Can you talk about shaping their narrative and relationships to each other and the land where they both felt they belonged, in different ways?

To me, their relationship really embodies a lot of what I have heard or felt or observed in Minnesota, in that tension between when European settlers moved into Minnesota and then after the [1862 U.S.-Dakhota] war, the treaties were abrogated and that small reservation was actually taken back. But before that time, the Dakhota lived across the entire southern half of Minnesota, and well beyond that. So in a Dakhota historical sense, all that land is still homeland. It's still the place where ancestors are buried, where they've had this thousands-of-years-old history of belonging to that place and knowing it intimately, and then to have people come in and basically displace you from it. . . .it brings us back to capitalism again. You put a price tag on a piece of land and then you own it. It gives a different sense of entitlement. This was something I really was trying to convey through the book, was this bumping up of worldviews that are so different in the way they see the world around us, the relationships, and they just keep bumping into each other. How do you reconcile that? How do you reconcile the Dakhota sense of having homeland for thousands of years, and then to be removed from it, and then to come back, but basically having to purchase your land that was your homeland, and to have people with that entitlement. To me, that is so complex.

Another part of the book that really struck me was the exploration of what wakes the seeds: water, fire, light. There’s a line where Gaby says to Rosalie, “Fire is a purifying force in the world. It cleans forests of dead wood, sterilizes as it scorches, and consumes us all if we let it. Some seeds need fire to sprout. What if you’re that seed?” Can you talk about this line, and the idea of embracing the different ways that seeds begin to sprout, both literally and as a metaphor for your characters?

It's always funny to reflect back on when you wrote something and you're just kind of flying along, and then be a little more analytical about it. What I was thinking about in that moment was that sometimes we respond to stress in ways that force us to take action or to come awake. I think of Rosalie, who was orphaned at the age of 12, and then put into a system where you are basically shut down, in a sense, and then to move into a marriage where she had hoped to find safety, just a safe place to be for a while. But, it's in what is an alien system. It continues to press her down in the sense of keeping her in that dormant state. So with Rosalie's family, I see this long line of women who have been seed keepers and who have really endured so much through their lives, through boarding schools and everything else, and here's Rosalie who is potentially the end of the line. The family has almost died out. She's lost connection to those seeds. She doesn't even know they exist. She's lost connection to her family. So I thought of her metaphorically as that seed that requires that fire, the intense stress, in order for it to germinate and then take action and begin to blossom.

I want to stay on the idea of embracing the fire. What does fire as a purifying force mean to you and how does it intertwine with the idea of protection and preservation?

There's a scene about a fire and the seeds. I actually had that dream, where there was a fire, and I dreamt that I was carrying those seeds, that they’re what had to be protected. I thought about that later, that those are the instincts that these women had, the instinct to protect your food source, no matter what, because you didn't have a Costco, you didn't have Cub, you didn't have social services or food shelves or anything else to rely on except yourself. Fire, to me, it's got the two sides of it. It's the simultaneous purging and cleansing, but it's also destructive. But then you see what happens after a fire out in the forest and the deadwood's gone and all of a sudden, there's all these wildflowers coming up. I love that. I love that cycle of renewal that happens with fire. That was a really key element in the story.

There’s a part in the book where Rosalie’s father says, “You can’t have science without caring about how it’s used.” He was talking about astronomy, but it applies to everything on earth. I think about the way science is kind of this siloed thing in academia and institutions. What are your thoughts about using care in science and having care and science be together? Because I think sometimes, at least in settler frameworks or institutions, they're not really talked about in the same sentence.

Yes. To me, that's Western science that has made that very arbitrary distinction. I think the extent to which we can consider ourselves “objective” is something of a myth because we bring all of our filters, we bring all of our experience, and while I believe you can have a rigorous process that really does your due diligence in research, it's never separate from who you are and it's never separate from everything around you. So that Western understanding of science is very different from an Indigenous understanding of science, which is all about place. There is a great book called Native Science by Greg Cajete. It's one of my favorite books. I've got it underlined, I've got it marked up. He talks about the metaphoric mind. He talks about how science has to be relational as well. You can't take it out of life and its context with everything else around it and say, "There's just this." That's why I think technology has gotten so out of control, because it never takes into account what's going to happen in the future. It doesn't take into account the consequences of it, meaning some of the pollution or the using up of resources or nuclear power, when we think about waste that's going to last for thousands and millions of years. That's unethical in my mind. What you've done is borrowed or poisoned the future for your grandchildren. That's not right. So science has to have ethics. It has to have a relational connection to the world around it. That book is just a beautiful way of understanding science. That's my foundational book.

Where are you finding hope or joy or inspiration right now?

Plants, seeds, food, anything to do with the outside world. To go out and garden, to have my hands in the soil, to walk out the door in Minnesota in March and hear birds singing, because our winter is very, very quiet. So to hear birds singing as they're returning on their migration, and the fact that when all that craziness was happening, the political coup and everything, they didn't care. The birds keep singing. The world around us is just profound in its disconnect from what humans get so excited about. I think of that as a really good check and balance for our priorities. Writing, reading, working with native writers: those are all joyful places to me.