You do not have to find the beginning at all. It is a primordial situation, so there is no point in trying to logically find the beginning. It is already. It is beginningless.

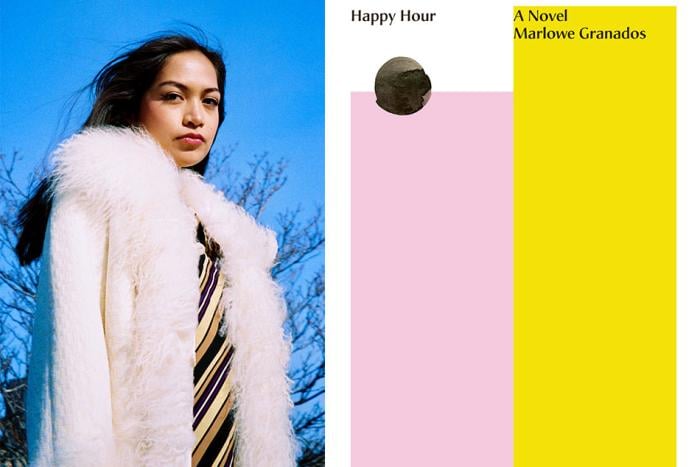

-Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

This is my mother: a scant four-foot-eleven, narrow-shouldered, and a kind of very-thin-but-soft that comes from treating both food and exercise as tolls paid for being alive. She doesn’t drink because it makes her fall asleep, never wears makeup, hates to shop. Her wardrobe is mostly hand-me-downs from her children. She still wears a pair of navy corduroys from Jacob Junior (vintage 1998) with a ladder of wear lines at the ankles from each time the hem was let out to accommodate my brief and only middle school growth spurt.

When she was a toddler, my mother pulled a pot of boiling soup off the stove and over the right side of her body. The scars are frames frozen from a home movie—a play-by-play of the accident that caused them. The taut, shiny nucleus on her elbow splashes outward, the skin buckling and creasing as it spreads, a second splatter over the outside of her right leg where her knee meets her thigh. Over the decades, these scars have ceded territory to the soft, freckled skin around them. If you met her now, you might not even notice.

When my mother was a child, though, the damage was notable. Her own mother insisted she always wear dresses with three-quarter-length sleeves to hide the worst of it—that blight on my grandmother’s parental record—and so my mother’s back-to-school Septembers on the humid bay between Coney Island and mainland Brooklyn were woollen and stifled.

As a teenager, my mother developed scoliosis and was locked into a full-time back brace designed to bully her spine upright. The brace was metal, and graceless, and ‘50s. A bear hug from a robot. It didn’t even work. If you stand behind her, it still seems as if the upper and lower portions of my mother’s back are keening in opposite directions; the left hip leans in to confer with its neighbouring armpit, while the opposite shoulder blade wings back. It’s like a visual effect, an optical illusion. The brain does a kind of stutter-step, trying to straighten out the error. My father has always liked to take moody, poetic photographs of people walking away from the camera. There is nothing my mother hates so much as a picture of herself from behind.

When I describe her physical presence, it seems as though the sum of mother’s parts ought to add up to a tiny, broken, bird-like whole. That’s not my mom. In fact, my mother is exactly what people mean when they say someone is a force. She walks the streets of Canada’s placid, nature-laced capital at an emergency clip, stopping traffic to jaywalk by thrusting her palm and belly-yelling “Heeeey!” at stunned Ottawa drivers. “I can’t believe I’m short,” she complains. “I feel tall.” She never answers the phone with a question: it is either a stunted, declarative “hello” or, if she is really cranked up to full speed, she flings her full name, first and last, into the receiver in a single, hurry-up breath. A storm of will and decisiveness, she is an American in Canada: unassimilated, unaffected, and—the cardinal Canadian sin—unapologetic.

It’s the deepest corner of winter and twenty below (“but it’s a dry cold,” we incant, protecting exposed flesh against frostbite and stuffing long johns under jeans). The snow banks pile and tower, and it’s hard to open your eyes as much for the cold as for the light, which has a determined, proselytizing way of getting at your retina from every angle. Hunkered indoors, wrapped in a blanket and wearing a highlighter-coloured hoodie from a soccer team I played for almost twenty years ago, my mother looks out into the frigid glare and asks like she means it: “Why do I live here?”

In 1959, a pack of Buddhist monks and nuns several-hundred strong walked out of Tibet and over the Himalayas into India, fleeing the Chinese invasion. Among them was Chogyam Trungpa, a nineteen-year-old lama who’d been plucked from a tribe of nomads as a toddler when he was identified as the eleventh reincarnation of a great Buddhist teacher in the Kagyu lineage.

Though he was raised in a monastery, the teenaged Trungpa’s spiritual path was proving neither straight nor narrow. On the gruelling march out of Tibet, he had a love affair with a fellow refugee nun. (She was later kicked out of the order when she gave birth to his son; Trungpa was allowed to remain among the fold.) In India, Trungpa devoted himself to the unconventional, worldly task of learning English. His intellect and curiosity earned him the attention of sympathetic Brits, who arranged for a scholarship to Oxford. In 1963, the young monk went West.

Trungpa and a fellow lama-in-exile established a monastery in remote, rural Scotland—the first of its kind outside the east. The Telegraph ran an article in its glossy weekend supplement featuring a full-page photograph of the dozen or so Samye Ling residents gathered on the monastery lawn, standing behind a grinning Trungpa, his ruby robes a warm shock to the grey-green Scottish hush. This picture inspired a flutter of pilgrims, some of whom left jobs, school, and homes, turning up at the monastery on foot, trekking for hours from a transit station twenty-five kilometres away.

While his co-founder pictured a sanctuary for Tibetan Buddhist ideas and teachings, Trungpa had different ideas. He taught like he was in a college dorm, gathering students in his room to stay up all night drinking and talking about the nature of reality. He wanted to attract Western students, to meet them where they were.

Besides, Trungpa had discovered he enjoyed the pleasures of a more secular life. In 1969, he blacked out (likely drunk, but no one knows for sure) at the wheel of a sports car and crashed into a joke shop, leaving the left side of his body partially paralyzed. Taking the karmic punchline to heart, Trungpa saw the accident not as the result of drinking and driving, but rather as a cosmic rebuke for having disguised his bodily desires by dressing them up in a holy mantle. And so he gave himself to the former, and gave up the latter, renouncing his monastic vows and his robes to become a lay teacher. Scandalizing British and Buddhist alike, he took a sixteen-year-old schoolgirl as his child-bride, and in the first days of the new year and the new decade, the guru headed to America.

My father is an athlete who hails from a time when you didn’t stretch or build or work your muscles—you just used them until you couldn’t anymore, and that was sports. Too slight to carry on with football past high school, he took up cross country running when he went to university in Ottawa. He says it was the island of misfit varsity athletes, eccentrics who woke before dawn to crack eggs on their teeth and open them into their throats, run punishing distances along the Rideau Canal.

My father is in his 70s now, and despite an old-man gut and arthritic hips and a turning radius of maybe thirty degrees in his neck, his endurance is insane. He still outlasts people decades his junior at activities he shouldn’t even be capable of doing anymore. He stops to play a few rounds of tennis en route to a hip replacement consult. At Christmas, we all haul up to the Gatineau Hills outside Ottawa to go skate-skiing—an ultra-aerobic sport that will burn half a day’s calories in a session—and my septuagenarian father cruises gracefully over the snow for hours, leaving me, my sister, my track-star brother-in-law all struggling in his wake. He laughs and yells at us to hurry up, white hair floating around his head in tufts like an expressive, dying weed.

He didn’t go white by way of salt-and-pepper, nor bald by way of any kind of pattern; his hair just leached both colour and volume for twenty-five years, always thinning and never quite fully gone. He often carries booze on him when he skis, his athletic force of will equalled by his hedonism. Leather wineskin on his hip, his blue eyes sparkling under the frost caught in his eyebrows, he is like something out of a Nordic faerie tale: a red-faced winter gnome, harbinger of mischief or joy.

The second son of a Wing Commander, my father was raised reliably transient, moving every other year to government-issued homes across a litany of Royal Canadian Air Force bases. After skipping a couple of grades, he was shuttled off to university early, his education paid for by the military in exchange for the promise of service

At summers spent in basic training, my father liked the games. He liked being blindfolded and dropped in the woods in the middle of the night, commanded to scrap and survive and find a way back by dawn. He liked placing in the middle-distance events at the annual base track meet. He hated everything else: the rules, the yelling. This bullshit of lines so straight and narrow there was no room to move or swerve or look around. It was as if everything that would ever happen to you had been preordained, and life was only a matter of putting in the time. When he dropped out of the army, he gave his resignation to a fat-faced General with a row of stars blinking from his shoulder. This man knew my grandfather and took it upon himself to play paternal proxy, telling my dad that his life would be a waste, that everything he touched from now on was destined to fail.

My father got a job as a radio announcer for the overseas forces—a gig he scored with a charming interview, in spite of what he will admit is not a classic radio voice. He spent the years people mean when they say the ‘60s in Europe, getting high and learning that wine comes in varietals, not colours. He would stay up all night and drink bottomless coffee all day while he broadcast the news in his floaty tenor for the benefit of people living under the command of something he’d walked away from.

He dated French women and told himself he found armpit hair attractive. He drove a motorcycle, got into an accident that really should have killed him trying to jump a watermelon patch just to see if he could. He went to Turkey, to Greece, hung out on Mikonos before it was that Mikonos (I’m pretty sure Lindsay Lohan owns it now). When he travelled, he didn’t worry about where he’d be at nightfall—he could curl up anywhere, snatch sleep at the side of the road. He wasn’t afraid. He drove with a friend across a border (don’t ask which one, but trust me when I say it was a bad idea) with a brick of hash inside the car’s wheel, thudding ceremoniously on each rotation as they cruised past the armed checkpoint. He was dared to do a handstand on beer bottles, and when the blood leapt from his wrist it arced all the way across the bar like it had been waiting its whole life to try that, like it was answering a call.

At the end of the decade, my father came home to drop out. He moved to a cabin outside Sooke on Vancouver Island, joining what might now be called an intentional community had the whole point not been to avoid the goal-orientation of intending anything at all. A kind of low-key, lazy man’s commune: the non-binding associations of the likeminded and deliberately lost. There were draft dodgers and deserters, drop-outs and drug-addicts-to-be. No one was going to judge or lay a trip. The only dirty word they knew was “should.”

Like most of his friends, my father planted trees in the summers and bobbled through the rest of the year on EI. There was plenty to keep him busy. Some of his friends had dropped out of science degrees, and they were putting their first-year chemistry knowledge to use, working their way through the branches of pharmacology, figuring out which drugs and how much to go up, or down, or outside yourself. This was terra incognita, and they didn’t have a guidebook. There’s a difference between trying drugs and experimenting with them.

It was also pretty common to dabble in spiritual practices and mysticism. Like anything else, it was all just an experience to be had. Try it out, see if it felt good, move on if it didn’t. Some of my father’s friends were into meditating, so he did a bit of that. A couple of others got into Hare Krishna, and he used to sometimes hitch a ride with them into Victoria, chant a few hare-hares for the free food.

In 1974, my father and some friends drove to Boulder, Colorado, to attend an event they’d caught wind of (how did they know without Twitter?): a series of East-meets-West lectures, courses, and readings organized by Chogyam Trungpa’s growing organization, Vajradhatu. Ginsberg was there, as were Gregory Corso, John Cage, and Ram Dass, among others. This would later be called the First Summer of Naropa, and the summer session would secure the founding of the liberal arts college Naropa University, where Ginsberg, one of Trungpa’s most famous students, would found the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics.

My father liked meditating, and Buddhism intrigued him, but he wasn’t searching for a path to follow or a guru to lead him down it. He was still wary of anything that demanded too much compliance. But after several years of trying to not think too hard about anything, he had to admit that Trungpa’s lectures blew his mind. He describes the experience as “an intellectual feast.” Naropa was run in two six-week sessions, and my father had intended to attend both. Instead, he bailed out of the second round of classes, joining up with a group of Trungpa’s followers as they headed into the mountains to deepen their practice with a month-long meditation retreat.

In the early ‘70s, my mother went to law school at night and worked two jobs during the day. One was at the South Brooklyn legal aid clinic. She loved this job—she felt she was learning a lot, doing work that lined up with her politics and ideals. That’s where she met a clinic volunteer named John. He called himself a “spiritual seeker,” which is, apparently, something men in the ‘70s said unironically to women they wanted to date.

They started going out. One weekend, John borrowed my mother’s apartment and laid himself out in a shrine of candles and sweet grass. He left a note saying that should he stray too deep into the Bardo and not be revived, she should ring a bell and softly chant a mantra in his ear. If that didn’t work, he’d left the phone number for someplace in Vermont called Tail of the Tiger where she could reach the followers of a man named Chogyam Trungpa. They would know what to do.

Trungpa came to New York to give a talk, and John brought my mother along. The event was a in a church basement, and my mother remembers that Trungpa showed up an hour-and-a-half late, which, it would turn out, was typical. As he spoke, he downed glasses of what my mother believed to be water (she would later learn it was sake), and after the talk he was carried offstage by helpers, which my mother assumed was a result of his paralysis (retrospect: he was too hammered to walk).

My mother’s first impression of Trungpa was more or less a shrug. She wasn’t seized by the specialness of the experience, but neither was she bored or turned off. She was, as she puts it, “open.” At John’s encouragement, she started attending a meditation class at the local dharmadatu and found she liked the practice a lot. She describes it as “totally unintellectual.” Where the law was often abstract, sitting meditation felt concrete. A way to quiet both her body and her mind. In 1974, my mother and John decided to go to Boulder for the Naropa lectures. She couldn’t get the time off work, so she missed the first session, but turned up for the second.

***

Trungpa was reviving a tradition he called “crazy wisdom.” This was his interpretation of the Tibetan notion of drubnyon, stories reaching back to the 15th and 16th centuries of monks and holy men who were charged with profound spiritual knowledge but behaved in convention-defying, disruptive ways. Trungpa embraced this part of the Tantric lineage of Buddhism he’d inherited. He put crazy wisdom at the centre of his teachings.

It was a smart move as far as American branding efforts went. This was the ‘70s; people liked to party, and Trungpa’s students were drawn to the idea that their serious spiritual endeavours might get raucous. And though Trungpa warned against this simplified, goal-oriented approach to the Vajryana path, he dosed his own example of wisdom with plenty of crazy.

What this looked like: he might burst in on a student while they were taking a shit, ask another about her masturbation habits, cut someone’s hair in their sleep. Students remember that he had a talent for divining deep sources of shame or pride and conjuring the swiftest, most shocking way to expose them. And if the means were ruthless, or violent—that was strategic. Trungpa would say that the brutality was necessary in order to wrest a person’s spirit from the clutches of their ego, to disabuse them of the lies the mind tells when advocating for the primacy and coherence of the self. He would claim that this kind of first-person narration—thinking of oneself as a consistent set of facts, as a singular “I”—only keeps a person bound to a version of the world that is aggressively self-serving, and thus spiritually impoverished.

Trungpa did not only target his student’s frailties: he also offered himself and his own frail body up in service to the cause by drinking heavily, smoking cigarettes, and having sex. This, he said, was a means to dispel the myth of a guru as sacred or pure. He claimed to be forcing students to confront their expectations of spiritual authority, making them recognize just how conventional those expectations were.

It was hard to say when Trungpa was guiding you down your spiritual path, and when he was body-checking you off of it, destabilizing your attachment to the journey itself. He was as likely to issue warm words as he was to fuck with you, totally mess with your head. Both approaches were equally valid, equally crazy-wise. This gave rise to a culture of relentless self-examination among Trungpa’s followers. The guru would act, and students would observe their own reactions to his behaviour, scanning for signs of their own resistant egos to unpack, dismantle, and discard.

***

At a meeting of Trungpa’s followers in Boulder in 1976, my mother was with the party from the Manhattan sangha—the largest in North America—while my father represented the flyweight dharmadhatu from Nelson, BC, which, at a dozen or so practitioners scattered throughout the Kootenays, was Vajradhatu’s smallest.

My father met my mother, but she didn’t return the favour. He noticed her laugh and remarked on her ability to wrangle the higher-ups in the Vajradhatu organization. Buddhism notwithstanding, he says they were just like any bureaucrats made petty by power, and my father was impressed with how my mother seemed preternaturally able to navigate the system. That my mother didn’t notice my father’s existence doesn’t surprise him. “I didn’t say much,” he tells me. “I was kind of a clueless bumpkin.”

Her first memory of him comes two years later, when they both attended an annual meditation retreat called Seminary. Seminary was no joke. For three months, a group of ninety or so committed students sat and meditated for up to twelve hours a day, then listened to Trungpa give talks at night. The experience was designed to mimic the phases of the traditional Vajrayana path, moving first through an examination of your own mind, then a period of outward-facing compassion, and finally brushing up against tantric, ecstatic knowledge. By the third act, Seminary became a nightly rager.

In her version, my mother would get “crazy” by singing show tunes and ‘60s bubblegum numbers with some pals. (When she tells me this, she does a shoulder shimmy and sings the chorus of “Rubber Ball” to demonstrate.) My father—who’d come to the retreat with his then-wife—had a different experience. “Your father was spending a lot of time with another woman who was actually getting married at Seminary. And her fiancé—who became her husband—was sleeping with Trungpa Rinpoche’s wife,” my mother explains, matter-of-factly sketching out the intra-Buddhist banging network.

Monogamy was seen as pretty uptight, my mom remembers. But this was one part of the scene she was never into. “There was one guy in New York who was, quote, ‘putting the moves’ on me,” she says, doing the scare quotes with her hands. “When I found out he was married, I said I wasn’t interested. I think that would have been surprising. Most people we knew just didn’t back off for those reasons, but I did. That was a very strong value for me, personally.”

***

In his early days in America, Trungpa’s message attracted mostly hippies and dropouts. Trungpa wanted to fully experience the world his students lived in, but he also found their tastes kind of gross. They dressed shabbily and spoke imprecisely, their music was noisy, they arrived in a haze of patchouli and weed. The guru was down to do the Western thing, but he’d been hoping for something a little higher shelf.

Which makes sense when you remember where he was coming from. Tibetan Buddhism isn’t democratic and chill—it’s rigidly hierarchical. Trungpa had abandoned a holy posting he’d been groomed for his entire life, giving up the tradition that had raised him on the bet that delivering the dharma to America, in an American way, was his true spiritual vocation. Now that he’d arrived, he wasn’t content to reach the far-out fringes of the counterculture. He wanted to find the centre. He wanted to go mainstream.

The way he went about this was not always on point. Some of his students like to remember him as a chameleon who preternaturally insinuated himself into American life. Frankly, that portrait ignores a lot. Trungpa was really more of an Anglophile, and his tastes ran aristocratic in ways that showed a naïve understanding of where exactly the pulse of his adopted culture lay.

He would go full Pygmalion, making students croon elocution drills in the Queen’s English like a mantra for hours at a stretch. He was a sucker for rituals of precision and performance: Japanese tea ceremonies, flower arrangement, archery, meals with a full entourage of silverware fanned around the plate. He ordered bespoke military uniforms—with crisp, white, unspecific colonial flare—and occasionally wore them to deliver talks. The British teen he’d married was a horse girl, and so the equestrian sport of dressage—a sort of ritualized prancing—was tossed into the mix.

The details of this syncretism sometimes missed the mark, but the broader point was this: Trungpa wanted his students to get their shit together. Because in a weird way, he was kind of a conformist. Despite his shock tactics and irreverence, his claim to be exposing the limitations of convention, he also had a pragmatist’s belief that if you want to change a system, you have to do it from the inside. He demanded his students be joiners, that they groom themselves for the world, enter into society with others. And so even as they delved deeper into an esoteric spiritual practice, Trungpa devotees who stuck around also started wearing suits, cutting their hair, getting real jobs.

My mother is a do-er. It’s like she can’t even help herself: once she’s identified a problem, she steps in and runs the show until it’s solved. This is not a characteristic everyone on the seekers’ circuit necessarily shared. A little know-how was a useful asset. And so at the New York Dharmadhatu, my mother was called upon (or did she volunteer?) to plan and stage-manage events, handle visitors, help out. She soon found she’d meditated and managed her way into an organization she’d started out with only a casual interest in. At some point, she actually moved into the Vajradhatu, living in a one-room loft off the shrine hall. At some point, she and John broke up.

My mother moved to Boulder, Colorado, because Trungpa’s next-in-command, the Vajra Rejent Ösel Tendzin (a white guy from New Jersey, né Thomas Rich) asked her to. Boulder was where the Vajradhatu action was, and they needed someone to play second fiddle to the organization’s legal counsel. My mother would be working under a senior male lawyer, naturally, but it was implied that keeping things on task would be up to her. And so, for a pittance of a salary and an appeal to duty, my mother gave up a good entry-level job with the federal government and her post-shrine apartment—a tiny but affordable place in the borderlands between Greenwich Village and Chelsea. The dharma called, and she answered.

In Boulder, things were getting, as my mother puts it, “just weird.” Trungpa and his family were living in a large house called the Kalapa Court, which they shared with a complement of attendants. The vibe was very Upstairs, Downstairs. Adherents would put on frilly maid aprons and butler’s tails in a ritual that was considered a kind of meditation through service. Dinner would turn into an elaborate game in which, it seemed, part of the point was to lose track of who or what was being spoofed. In a similar conflation of irony and sincerity, Trungpa started a paramilitary organization in which Buddhists would train to be warriors of the dharma, performing marching drills and setting off cannons in their all-khaki uniforms.

And then there was the Shambhala thing. In Buddhist lore, the Kingdom of Shambhala is a utopic, peaceable society guided by compassion. It’s generally considered a metaphor, but Trungpa intended to make it a real place, moved by visions he’d begun having as early as his flight from Tibet. Boulder didn’t seem like the right place to break ground. The vibe was wrong, the living was too easy. Materialism was so tempting in America. Trungpa wanted to find somewhere more remote. With fond memories of his time in Scotland in mind, he looked to Canada’s “New Scotland,” setting his sights on the craggy, rugged coastline of Cape Breton, and Halifax, the nearest major port.

At the time, the Shambhala wing of Trungpa’s plans was a partial secret, known to some but not all of his followers. Trungpa considered it a terma—esoteric knowledge that had been revealed to him prophetically, and which he must in turn reveal to followers only selectively. My mother was in on the partial Shambhala secret. But she didn’t like it.

“The idea was that you already had a place in the Kingdom, you just didn’t know what it was yet. So, when I was introduced to Shambhala, I discovered I was already the Kingdom’s Deputy Minister of Justice” she says. “I mean, honestly. Can you imagine?”

Being privy to the Shambhala vision meant an invitation to the Kalapa Assembly: Trungpa would rent out an off-season ski resort or dude ranch and bring his courtiers to plan their Kingdom and revel. He held balls, and the enlightened would assemble in gowns, tails, and white gloves, playing at being lords and ladies. It seemed a long way from Brooklyn and the legal clinic.

“I started to think: Okay, this is really crazy,” my mother says. “I kept thinking: what am I doing here? Where have my values gone? But people would tell me: oh, don’t worry, it’s a metaphor.”

She wanted the perspective of someone wasn’t dealing in all these metaphors and riddles, dressing things up and stripping them down, parsing and re-mixing crazy into wise and back again. But she felt she couldn’t talk to family and friends about it: the first rule of Shambhala was you don’t talk about Shambhala, and she’d sworn an oath not to share the secret with unenlightened commoners.

“That’s when you start to wonder whether you’ve been drawn into a cult,” she says.

***

I wrote about all this for a class once. This was in America, where the creative writing workshop was invented in the mid-century and ritualized into what’s practiced in universities today: the author bound by silence, the rest of the class working through a process of praise, deconstruction, demand.

In this workshop, everyone referred to Vajradhatu as simply “the cult” with a breeziness I found dislocating. I considered that maybe I’d been going around with my head tilted to one side, trying to make everything look complicated, giving myself a crick in the neck for no reason at all.

The character everyone was most interested in was my mom. Why did she stay in “the cult,” they wanted to know. How exactly did someone like her join “the cult” in the first place? No one found my explanation about her go-to-it-ness and urge to problem solve very convincing. It didn’t seem like enough, did it, to account for such a hard veer off-course, for winding up somewhere so extreme.

Not one but two people in this class of twenty used to be Mormon. One of them wrote beautiful, dizzying essays about false archaeological records, prophetic gold tablets dug up from American mountains, underwear laced with divine protection. When we talked about her work, the class spoke reverently about what it is to be a part of something larger—a whole world—and then lose the thing that kept you there. Everyone said the word “faith” like it was a tiny, fragile bubble they were releasing into the air.

In one way, North America was a spiritual seller’s market in the ‘70s, with plenty willing to join games of follow the leader. But things also cut the other way, and gurus were not exactly in short supply. Some came from away, bearing or claiming the authority of spiritual traditions from elsewhere (revealing how Westerners tend to fetishize authenticity if something is Eastern and old). Others were of the homegrown variety, declaring themselves according to the American tradition that all true authority, spiritual or otherwise, is conferred by and for and upon oneself.

The upshot: there were choices. Listen, and you’d hear any number of calls to which you might answer. Differently put, you might call out with your troubled questions and find any number of sources willing to deliver answers: religious noblesse, enlightened philosophers, nascent Ponzi capitalists, whackadoo clowns. Seek and ye shall find something or other.

Chogyam Trungpa often warned that spiritual practices are, themselves, highly susceptible to hijacking by the ego. He called this the paradox of “spiritual materialism”: how enlightenment can become goal-oriented and thus subject to all the pettiness of competition, envy, satisfaction, pride. Under the influence of spiritual materialism, self-consciousness is like a superbug, feeding on every attempt to eradicate it. Even a good-faith effort at spiritual growth might only exacerbate the conditions under which self-involvement thrives. So if you’re enjoying the journey, feel like it’s doing something for you, seem to be getting closer to an enlightened end—Trungpa would say that you’re probably doing it wrong.

Chogyam Trungpa was a guru who both totally embodied and totally rejected the trappings of the role. Part of his appeal was a downward mobility, holiness-wise: he didn’t seem to hold himself aloft, hadn’t made himself inaccessible in his enlightenment. Students took this as a kind of democratic generosity, even sacrifice. Trungpa was more fun than your average guru, but also more fallible. It was a kind of lifelong, full-bodied act of translation: the spiritual making itself accessible, allowing itself to be corrupted by the impoverished conditions of the material in the process. As his students imagined it, Trungpa chose to live in the world because he was choosing them.

But while Trungpa would say his more radical behaviour was meant to destabilize the implications of authority itself, the claim to be manifesting crazy wisdom also implied an authority and power beyond reproach. The logic of crazy wisdom was a total surrender to Trungpa’s whims—faith that whatever he did, no matter how outrageous or shitty, it was ultimately serving some higher-order aim.

The first time my father took the LSAT, he practically flunked it. He’d driven all night through a blizzard and across the U.S. border to get to the nearest testing centre in Spokane. But when he sat down and opened the standardized booklet, he realized he’d made a mistake. “I had barely read anything for about seven years at that point,” he says. “A little bit of Buddhist stuff, but I never saw a newspaper or anything, and my reading speed had slowed to a crawl.” The test wasn’t that hard, but he didn’t finish a single section. Between that and a mixed bag of out-of-date marks from undergrad, law schools turned him down.

He kept planting trees. A couple of years later, Vajrayana was recruiting Canadian followers to set up shop in Halifax and establish a dharmadhatu there. My father and his first wife had split, and there wasn’t much tying him to BC. He answered the call.

Before heading to the Maritimes on his dharma mission, my father decided to spend another summer in Boulder enjoying the Buddhist social life. My mother was still working for the Vajradhatu council there. At that point, my parents had run in the same circles for years but had never really hung out. My mom saw my dad around, and one night, she invited him over for dinner. There was no food in her apartment when he arrived, so they went grocery shopping. He bought her toilet paper. They both say it was a great date.

One time when I was in my early 20s, I went on a cross-country lark to visit a pen pal I thought I might be in love with (it didn’t work out, but that’s another story). When I emailed my mother to tell her my plans, it felt like a confession: admitting that I could be so irrationally moved by romance. I thought my practical mother would tell me to make it a round-trip bus ticket or remind me to pack a sweater, but she surprised me by saying she could relate. After all, she and my father had gone on only two dates (“might actually have been only one,” she amends) before he left Colorado for Halifax. He eventually started law school there. They wrote the occasional letter, and then he invited her to visit over Christmas.

“I did the irrational and flew from Boulder to Halifax,” my mother wrote to me in an email when I told her about the pen pal. “When the time came to actually get on the plane, I wanted to cancel, but my friends insisted I go. I complained all the way to the airport that I was crazy to fly across the continent for a weekend fuck.” This is classic my mom—no idea how funny she is, just telling the story as straightforwardly as she sees it. “Of course, we got engaged that week,” she adds almost as an afterthought.

If you ask my father, he will tell you about the full moon’s reflection scattered in the waves of Peggy’s Cove on the night he proposed. (He’ll forget to mention the part where she said no and told him to try again when he really meant it, which he did two days later to a better result.)

While my father waxes about the moon, my mother emphasizes pragmatics: they shared values, friends, a religion, a community. They were in their thirties. They both wanted kids. But it was his letters that drew her there, and surely she must have been taken with this, too: my father’s often gratuitous giving over to feeling, his unfakeable, earnest marvelling at just about everything around him.

These letters are long lost. I ask my dad if he remembers what he wrote, thinking there must be something there to foreshadow not only how these two people came together but, more improbably, how they’ve stayed there. I want to understand the origins of such duration.

“Well, I might have been writing letters to a few women,” my dad admits. “About seven or so? I dated a lot before I left Boulder.”

***

My parents were married at the Boulder Dharmadhatu in the spring of 1981. Before they could make it official, my father needed a divorce from his first wife—a detail that had been neglected. My mother represented his ex in the legal proceedings.

At their wedding ceremony, my mother wore a pale yellow dress, my father an ‘80s-loose grey suit. There was chanting in Sanskrit and a long bout of meditative sitting. Kneeling on pillows, my parents repeated their Buddhist vows in tandem: they promised to find refuge, together, in the Buddha, their example; the dharma, their teachings; and, finally, in the sangha, their chosen community of fellow travellers, their spiritual companions.

My mother’s parents—secular Jews born and raised in the Bronx—declined to kneel on the shrine room floor and perched on chairs at the back instead. “I don’t worry about them,” my grandmother said to anyone who would listen to her at the reception later, “but what about the children?”

I ask my mother now if she would have married my father if he hadn’t been Buddhist. She isn’t sure. She keeps coming back to what they had in common, trying to parse what came from Vajrayana and what didn’t. “We did share the Buddhist notion of mind as a construct, that you are not necessarily stuck with the thoughts that you have, that they are transitory,” she says. “But remember that when we got engaged, your father had started law school. A lot of our conversations were about social justice. That was a value we shared, and it brought us together.”

She pauses. “At least that’s what I’m hoping we talked about. I don’t even remember. Maybe I’m kidding myself. Probably we were just struck by whatever hormones were raging at the time.”

There’s a whole subset of human characteristics defined by the fact that we’re bad at talking about them: charisma, it factor, star quality, je ne sais quoi. These refer to the way someone makes others feel, not so much how they do it. When we say someone has it, that thing, we throw our hands up and admit defeat. It just is. You have to feel it. You have to be there.

The most compelling evidence I have that Trungpa Rinpoche was the real deal is something I know won’t be convincing to you: my mom was there. How can I explain to you how unlike her this is? How can I convince you that she isn’t the type? The very fact of her participation in something like this—whether you think it’s a kookily benign charismatic movement or a full-blown cult—remains a flaw in the prism I hold up to the world in order to make a mess of facts into something like sense.

There’s a rich trove of Trungpa content online: photos, transcripts, audio and video recordings. I’ve listened and watched and read a lot. Which isn’t to say that I understand, only that I’ve spent time looking. There are these moments in the archive I keep coming back to—places of heightened absence, where effects turn up orphaned from any cause. As if some crucial context has been left off, some detail eroded from the record over time.

Take this: a photo of Trungpa holding a gun to his own head, finger on the trigger, his other hand casual in the pocket of tailored suit pants. He’s wearing suspenders, a crisp button-up with stripes that change direction according to some frantic order, a kaleidoscopic tie. His gaze has slid off to the side, towards the weapon he has pressed to his temple, and his smile is taking up space, but seems faintly gripped. I find the degree of mirth impossible to track.

Or this: not infrequently during Trungpa’s lectures the audience flushes with laughter that seems spontaneous and inscrutable, responding to some quality of the moment that hasn’t crossed over to where I’m sitting. I listen to these parts over and over through headphones that promise to cancel noise, trying to catch a signal. This feels physical to me—more a matter of form than content. I picture the waveform opening, separating over and over, as if, by dividing enough times, it might eventually reveal some secret remainder, something I could touch.

When she immigrated to Canada, my mother was nearly turned away, flunking a mandatory physical screening over the concern her curving spine would be a drain on the bounty of Canadian health care. A second opinion was solicited, and several mounds of paperwork later she was waved through into Halifax, giving up her job and her country to join my father in what was then little more than a foggy, provincial port town.

Here, her world shrunk to Trungpa devotees and Kalapa courtiers, and my mother’s doubts about Vajradhatu only increased. She began to openly question where the organization was going. “If you leave, you’ll lose all your friends,” she remembers one woman telling her.

My father’s priorities were changing, too. My sister was born when he was in his final year of law school. His ties to Vajradhatu weakened casually, like a hobby you let linger in the basement, a friend you find yourself not making plans with and can’t quite say why.

My parents’ journey into Buddhism took a decade. The trip out was much quicker. After he graduated in 1983, my father got a job at a legal aid clinic in Ottawa. They got into their Ford Mercury Lynx and made what was then, on a less-developed highway, a solid eighteen-hour drive west—my one-year-old sister protesting her car seat, rain haunting them down the TransCan—and were never Buddhist again.

***

In September 1986, the same month and year I was born, Chogyam Trungpa made the Vajradhatu’s move to Nova Scotia official. A trickle of immigration had been slowly wending north, growing the Buddhist community in Halifax, and the enlightened Kingdom of Shambhala seemed to finally be in sight.

Within just weeks of arriving in Halifax, Trungpa’s heart and breath stopped, and though he was revived, he never really recovered. He died with all the hallmark bodily failures of acute alcoholism in April 1987. Witnesses claim that his body remained warm after death, suspended in a sacred state of Samadhi. They say the Halifax harbour—which had been frozen over out of season—broke apart and melted with his last breath.

In the wake of Trungpa’s death, hundreds of his American students made good on their guru’s wish and immigrated to Canada. As Trungpa’s succession plans had dictated, the Vajra Regent Ösel Tendzin —the same man who once told my mother it was time to be a good Buddhist and head to Boulder—took over the organization.

Even more than Trungpa had been, Tendzin was famous for a conflation of sex and spiritual instruction. Tendzin lead the organization for only a few months before it emerged that he’d been having unprotected sex with followers for several years despite knowing he was HIV-positive. He believed that Vajryana purification practices would protect him. Trungpa, he claimed, had told him so. All he’d done was follow the guru. A sangha member contracted HIV and infected his girlfriend with the virus before dying of AIDS. Tendzin fled with a small cohort of the faithful to California where he, too, died in 1990.

Though the Vajradhatu organization was shaken, it did not disappear, unlike so many other stunted branches on the ‘70s spiritualism family tree. The son Trunpga had sired in the Himalayas, Sakyong Mipham, was called to take his father’s legacy in hand. He eventually merged the two streams of his father’s work—the enlightened kingdom and the religious practice—coining the term Shambhala Buddhism in the early aughts. Not everyone was happy with this, but as a practical measure, it seemed to work. Home to a community of around two thousand Buddhists, Halifax remains the de-facto capital of Shambhala: a kingdom of some 12,000 practitioners spread across the globe.

In 2017, a second-generation Shambhala Buddhist (a “dharma brat” as those born into it are sometimes called) launched Project Sunshine: a series of reports documenting abuses of sex and power in the Shambhala Buddhist community. The reports include, among other things, consistent allegations against Trungpa’s son, Sakyong Mipham. From the outside, Mipham has always seemed mild-mannered almost to a fault—an unlikely inheritor of his father’s radical teachings. Unlike his father, who was, if nothing else, transparent, Mipham hasn’t made sex or drinking a part of his outward-facing persona. He has never publicly embraced the excuse that true wisdom is cracked open and wild.

The testimonies collected by Project Sunshine are highly specific, but also grotesquely, bluntly familiar. I’m starting to think that might be the worst part: how stories of abuse and its dissembling have already coalesced into a genre, a narrative dulled by repetition. I resent that I’ve become conditioned to expect all of it. I feel like I’m giving up something important about detail and nuance—something about how to value subjectivity.

In the years since Project Sunshine was launched, a never-ending series of Open Letters have come out from all sides, trading revelations and contritions and meditations back and forth, like call and response. Sakyong Mipham has largely denied the allegations against him, while also stepping back from his role as head of Shambhala and issuing the occasional mealy-mouthed statement of regret. In 2019, he left Canada for India and Tibet, where, according to an article published this September in the The Walrus, he’s rallying the faithful, paving the way for a return to power.

In one piece of audio from a Q&A at a meditation retreat in Vermont in 1974, a student asks Trungpa a question about romance. This student stumbles for a while, struggling to express himself, trying to figure out what exactly he’s asking. His concern, it seems, is that he’s doomed to trek the Vajryana path solo. That a budding awareness of the human condition has made him unsuited to love.

“I don’t think anybody can fall in love unless they feel lonely,” Trungpa tells him. “Nobody can fall in love with somebody else unless they know that they are lonely, and they’re separate individuals. And if by any misunderstanding, by any strange coincidence you think that you are the other person already, there’s no one to fall in love with.”

He goes on to frame this as a math problem. “One and one being together is union. Otherwise, if it’s just one, you can’t call that union. Zero is not union, one is not union. But two is union.”

Another student follows up: what’s the difference between a romantic union and the bond formed between any practitioner and the rest of the sangha?

“If two people are together, the types of loneliness may be a similarity. The fact that one person reminds the other person more of their loneliness. That you feel your partner feels you, seeing you more lonely.”

***

There are points along the Vajrayana Buddhist path where you have to commit. First an initiate will take the Refuge Vow, and later they will pledge to become a Bodhisattva—someone whose quest for enlightenment is guided by compassion rather than self-interest. In a formal ritual, the guru gives the student a new name, something to represent the thing that is both their strongest tool and also their greatest impediment. Long before they were a couple, at ceremonies at opposite ends of the continent, Chogyam Trungpa graced each of my parents with the same moniker: they are both “Highway of Patience.”

This seems to me like some real bolt-of-lightning shit. My father confirms that it’s an unlikely coincidence. He says he’s never met another patient highway, nor has he heard of another couple whose Bodhisattva names are twinned. “It’s very, very rare,” he says.

“It doesn’t mean we’re compatible or anything,” my mother argues. “It just means we have similar problems.”

My mother has pretty thoroughly rejected most of the Buddhist teachings she once followed, but this name still means something to her. “I have to work to be patient. And I wouldn’t have said I was then, but I think I’ve become a good listener,” she says. “Probably having been given the name is a great influence. It’s not like I never think about it. I do.”

“Sometimes your mother and I have conversations where we just say, ‘Yeah, I know,’ ‘I get it,’ ‘You already told me that,’ ‘I know,’ back and forth at each other. Like two impatient highways running off in different directions,” my father tells me, laughing. “I think it’s funny that we have the same name. It’s neat.”

My father has started meditating again. He took it up a few years ago, when he turned 70, right around when he retired from a career in refugee law. “I’m pathetic,” he says, “I only do ten minutes a day.” He doesn’t kneel on the floor anymore, although they still have the dense, bright yellow and red meditation pillows that have been squatting in corners of their house for as long as I can remember. “Meditating is hard on the body,” my dad says. “My hip just doesn’t bend that way anymore. I sit in my computer chair.”

My mother is unlikely to follow. It’s hard to imagine her sitting still without being occupied by a task or four, and I’m sure she’ll never meditate again as long as she has an iPad. Lately, though, what she’s been talking about is learning Hebrew. She’s thinking idly about having a Bat Mitzvah instead of a retirement party. She’s been reluctant to talk seriously about retiring at all, but maybe she would consider it, maybe, if she found a way to tie it to her roots, to a ritual with some meaning. A coming-of-age. Maybe if she had a goal.

***

At their wedding, my parents professed their faith to a set of laws they no longer follow. They promised to build their union within a community they’re no longer a part of—one they’ve abandoned. The truth is, their vows are long broken. They’ve been married for almost forty years. I want to know: Do they feel a little weird about that? A little guilty?

“No,” my mother says in a Highway-of-Zero-Patience voice. “I don’t have that feeling whatsoever.”

I thought my father might be more nostalgic, but he doesn’t put much stock in it either. “No, no, I don’t feel weird about it at all. It’s just where I was at the time. Now it’s kind of an exotic story when you tell it at parties.”

I’m talking to them long-distance over Skype. They’re in Ottawa, in the house they’ve lived in since just after I was born, sitting side-by-side on the couch my mother has been carting around since her Manhattan days (a mod burnt pumpkin colour when I was growing up, since re-covered in earth-tone stripes). I’m in BC planning my own wedding. Without religion, I’m finding it hard to sketch the contours of the ritual. When I tried to write my marriage vows, they came out sounding like a murder-suicide pact.

My mother took a pottery class recently, and she holds up the results, showing me a series of wonky mugs that never quite found their centre. “Pathetic,” she declares.

“But the colours are fabulous,” my father adds enthusiastically. He’s mostly off-screen: a glimpse of his ear, stray white hairs wavering at the edge of the frame.

“Dad, I can’t see you,” I say.

“I’m eating chicken!” he calls, yelling too loud, sticking his hand in my mother’s face as he gives the webcam a greasy thumbs-up. She pushes his hand away.

“Pottery’s over. I need a new hobby,” my mother says. “Maybe I’ll divorce your father.”

“Good idea,” I say. “Something the two of you could do together.”

She leans into him for a moment. Skype starts to stutter and glitch, and their laughter comes out sounding like they’re being choked. The screen freezes: my mother’s eyes are shut, her head resting on my father’s shoulder. I can see half his face now, ruddy and pixelated, thrown back mid-laugh. For a moment, they are preserved this way. Then her neck jerks upright like a marionette, their movements drag in awkward bursts between tableau.

“What? What?” they say to the computer. “We can’t hear you.”

“Give it a second,” I say. “Just wait for it to pass.”

“You’re frozen! We can’t hear you!” They’re both yelling. My mother pulls on her glasses and leans towards the screen. My father’s head moves out of view again. “It’s not working.”

“Just wait,” I say.

A lot of people’s dads will tell you they were a hippie back in the day. I suspect this means they smoked pot in university, went too long between haircuts, wore jeans with flagrant ankles that now seem like a punchline.

My dad was a dropout. For most of his twenties and into his thirties, he was off the grid. His beard and hair straggled below his sternum, ruddy and sun-scorched. He got fucked up on whatever weird, hard, home-concocted drugs came into his orbit. He got fucked up on solitude, living alone—one year, or maybe it was two—in a cabin he jerry-built right into the side of an ancient spruce, cobbled from driftwood and washed-up lumber, squatting on a beach of crown land on the western edge of Vancouver Island where thousands of unbroken kilometres of Pacific Ocean hurled up storm after wild, grey storm. He didn’t go to the doctor. He abandoned his bank account. He forgot how to read. That my father became a man who wore a suit to work, who made a career of helping people, who knows and follows and teaches society’s laws—I don’t know what to call that but a miracle.

This an orienteering tale: a man is lost in the woods, and he tracks his way back to the world. And because of all those dads like mine, dads in suits who remember that they were there, too, I find it hard to place just how common this sort of thing is. In one way, it might be the story of late-20th century counterculture and its aftermath: trying to ditch one set of values on a quest for something more spiritual, more true, only to wind up at some very hard, material centre. Maybe it’s only the story of how, by trying to shake the rigid ‘50s, all we got was the empty, plastic ‘80s.

Is this version sad? All that pointlessly performed freedom, all those ideals failed and abandoned. The world never renewed at all, just more and more of the same. It’s a huge bummer when you add it all up, when you call it a generation. It’s bummer when you are the direct product of it, and your whole life exists in the long, stupid hangover of what’s left. But hone in on just one individual, and the movement out and back isn’t so easy to characterize. Surely it’s better than one very real alternative: staying dropped out until it’s no longer something to choose. Never finding your way to any path at all. Dying, maybe, or else doomed to be permanently ancient, wandering coastal highways and lingering on downtown corners, so long burnt-out you register to others only as dust.

My father says that when he thinks about this juncture in his life, he pictures an escape sequence from an action movie. A huge, metal door descends, aiming for the ground with its great, final weight, and he’s diving and rolling, just barely passing through a narrow opening before it disappears. In the movie version, the hero crosses the threshold because of his quick reflexes, his strength of will. Because the story is his, and the story is always out there, on the other side of the door. In real life, my dad tells me, it just isn’t like that. He senses that the counterfactual still has some claim on him. And the difference between stepping into the rest of your life and being crushed right there on the brink, or left behind and forgotten: he says it isn’t anything but luck.

My mother’s story is less common than my father’s, I think. Or maybe it’s the same story told backward, turned inside out. Maybe you have to play the record in reverse to hear it. Before she met Chogyam Trungpa, my mother hadn’t been sent spinning out to society’s fringes. She wasn’t off the grid; she moved across it like it belonged to her, speed-walking down Manhattan streets, stopping cars with her hand. She was twenty-five years old, fearless with optimism, making good on her parents’ every hope for intergenerational mobility. She lived among the tallest buildings. She had a million boyfriends. She was in the centre of the world.

“I think about this every once in a while,” my mother says. “How my life in general has moved along: in the ‘50s it was rock-and-roll-pop, in the ‘60s it was Beat Generation, and then in the ‘70s: I got religion! How is that possible? What a freaking cliché. I look back, and I can tell you all the things I thought were important, all the decisions I thought I was making. But now it seems that I was just so much flotsam and jetsam, moved along by the Gulf Stream.”

What if something is both a guiding light and a hard wind; a true north calling the wayward compass into line and also the entropic force that blows everything apart, sending particles fleeing from security or pattern or sense? What if you feel it, follow it, and this is what you get: a whole lifetime of exchange with another human being, bound by a promise to pool your resources, your reason, your pleasure? Say you mix yourselves up right down to your very cells, mingling the most ancient codes your body keeps, trading all the secrets it knows.

That’s such a crazy thing to do.

It’s tempting to abuse retrospect, to herd so many coincidences, so many little hooks of karma, or plot, until the present falls in line, giving itself up as an inevitability. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche—my parents’ bizarre, unlikely matchmaker, his voice ready to gloss on their story—would probably say that this kind of mythologizing is the very worst kind of ego. There goes the flailing, neurotic “I” grasping for coherence, asserting its own importance. I’m sure he’d say I’m doing a lot of things wrong.

The dharma Trungpa taught was an invitation to find comfort in instability, to be at home in impermanence. He taught that living could be both immersive and yet, still, somehow a release. I don’t know if he was good, or right, but I still ask myself often if I could do it: be all the way in the world without trying to gather everything up and hold it, take it with me, take it apart. I ask myself if I could ever love something without thinking, always and always, about how it will die.

I don’t know if where we wind up, or who we get there with, is a measure of anything like purpose, traces of tectonic forces slipping and pushing beneath what seems like boring, everyday stillness. That it’s unlikely doesn’t stop me from trying to catch it. I know it doesn’t matter, that there’s no point in parsing the difference between choice and fate. Even if you believe in the latter, it’s not like the former stops happening. You have to keep existing, and that’s always just a little bit tensile, a little bit decisive. You can’t discount the possibility what you were fated is, itself, the opportunity to choose.

Here’s something I’ve been thinking lately: maybe believing in anything—like, seriously, anything at all—isn’t a matter of being faithful to gods or gurus, to organizations or other people. Maybe it’s only a weird kind of loyalty to yourself. Locating a feeling you’ve had and allowing the memory of it to be what you make promises to, letting its imprint be your lodestar. Maybe it’s just picking a version of yourself to act on behalf of. I have to think that even if you’re prone to hear a restless call like doubt, it’s still possible to build your life around some kind of certainty. Trust that you were right, and lucky, if you caught it even once. I’m saying just because something is a feeling, doesn’t mean it can’t also be a good idea.

And what your body wants, and what your body gets—I think that matters. I think it counts. You probably have to be there. You probably are.

I got married on an island in the Discovery Passage off the coast of Vancouver Island, on my in-laws’ rocky snaggle of Pacific rainforest land. I don’t remember what I promised in my vows, but I know I meant it. I know they’re written down somewhere.

The moment the reception started, my parents took to the homemade plywood dance floor, and within seconds they were owning it. That cinematic moment when a couple’s whirlwind sends the rest of the dancers to bob and sway and look on from the outskirts, pushed there by a centrifugal certainty that this moment is only theirs to witness.

The night we met I knew I needed you so. Ronnie Bennett’s voice warbles into the soft halo of light holding the forest at bay, those dozens of pine sentinels spindling towards a sky matted with stars. Oh, since the day I saw you, I have been waiting for you. You know I will adore you ‘til eternity. My mother’s eyes close and she tilts her chin up, shimmying her shoulders and punching the syncopated snare beat with jazz hands. My father spins, gyrates incomprehensibly, and flings her the full breadth of the dance floor as though they’re holding two points on a Spirograph before pulling her back in, closing the gap, his wildness tethering towards her simple grace in some hilarious, ecstatic, intimate pattern of their own making.

Bypassing hindsight to record this memory straight to the best-of collection, I laugh so hard I feel sick, leaning into the moment so fully and so headlong it seems I’ve reached the other side of it—someplace shimmering with morbid beauty, where my whole self churns with the wish to please keep just this one thing. And with this perverse, impossible prayer I give myself up like a band of film, open an aperture, and let the shards of silver skate and cluster to hold onto the only thing they can: all the places where light isn’t.