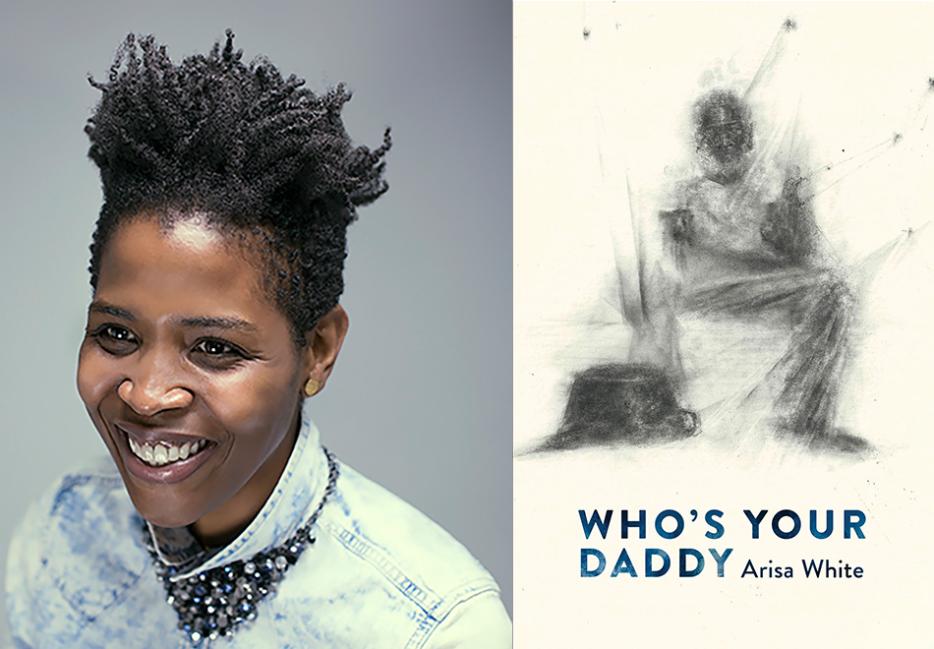

Poet Arisa White’s new lyrical memoir, Who’s Your Daddy (Augury Books, 2021) is a pencil box full of questions, and a lot of sharp answers. Or maybe they’re best described as discoveries, or observations, or fragmented memories. A memory of hiding behind a blue door, of being chastised for not separating the letters “LMNOP,” of a street corner burning with life while a man turns and walks away. “Who’s your daddy?” White writes. “A portrait of absence and presence. A story, a tale, told in patchwork fashion.”

She asks: “Am I a site of abandonment?”

Who’s Your Daddy arose from a decision, in White’s thirty-third year, to reconnect with her estranged father, who lives in Guyana. Growing up in New York, White parsed her memories of him, but whose memories were they? And were they of him? As an adult, facing the confusing and painful intimacies of the relationships that come with adulthood, White grows increasingly interested in questioning what the word “father” means, the influence it has on her life, the presence of its absence. She began with a project called the dear Gerald project (Gerald being her father’s name), soliciting letters from people writing to their fathers or father figures. She received an artists’ grant to travel to Guyana, where the hope was that she would meet her father, but the plan, either way, was to document the lived experience. White did meet her father, an experience rendered in Who’s Your Daddy, but the real crux of the story is the elegant ways in which the writing leans into questions, an embrace of exploring relationships of all types, a reckoning with love and grief and anger.

Arisa White is a prolific poet and artist, and her skill with words is unparalleled. Who’s Your Daddy is brief in length but long on the power of syntax, metaphor, and economy of space. Passages in this book are transporting and utterly profound. I spoke with White on the phone about paternalism, bodies, queerness as an action rather than an identity, and the non-innocence of language.

Sarah Neilson: Can you talk about the dear Gerald project, how that evolved over time, and how this book grew out of that project?

Arisa White: dear Gerald is the first iteration of Who's Your Daddy. It started when my mom asked me if I wanted to write my father Gerald in Guyana. That year was the year I turned 33, my Jesus year, so it was interesting that it all happened at that time. I didn't know what I would say to him. What do I say to someone who I haven't had a relationship with? My last memory with my father was running away from him and hiding behind a bedroom door. So I went to poetry. I started writing epistolary poems to make language for how I was feeling and to populate the distance with some sound, some expression toward him.

Basically, I would document my days. I was living in Oakland, California, at the time, and started to make connections between the San Francisco Bay Area and Jonestown, and began researching the history and culture of Guyana, and paying closer attention to my own memories. After nearly two years of writing epistolary poems, I applied for a grant from the Center for Cultural Innovation.

My project proposed a self-publication of one hundred copies of dear Gerald for which I would exchange for letters written to estranged and absent fathers, and patriarchal figures. I received letters from men who were in San Quentin, one came as far as the Philippines, and some students from Evergreen Valley College created a documentary in response to this question of who’s your daddy. I also facilitated community-based letter-writing workshops, and this was during the 2016 election, so people had a lot to say about our legacy of forefathers governing our daily lives.

The last component of the grant was a trip to Guyana to meet my father and give him a copy of dear Gerald. I’m there for two weeks, documenting my time in the country, keeping notes and observations about what I’m watching on television. I collect newspaper clippings, pamphlets, record my nightly reflections on how the day went and what I am feeling. So, I had all of this new material as well as the actual experience reconnecting with my father, of being in his body presence and recalibrating with this father frequency that gave me life—which is its own kind of expression that still feels inexpressible.

I want to latch on to what you said about your Jesus year, because I’m curious about the role of God and religion in the father narrative, and how it influenced or influences your thinking about what the word father means.

Once you pay attention to a word and its resonances, everything starts glimmering. At the time, I was doing historical research for my middle-grade book that I co-wrote [with Laura Atkins] called Biddy Mason Speaks Up. A lot of times, I was hitting up against the word paternalism in the context of the institution of slavery. To me, it shakes the body loose of all of its illusions. That had me thinking, as well, about the notion of God and how it’s put to a male body. I began to wonder, what are all of the mechanisms in the technology of God-making that's operating? It's operating in all of our institutions, it's operating as a system of control and enslavement. It's fascinating to follow the words and what they get attached to.

My father, during my visit to Guyana, requested that I take care of him. He could feel empowered [to ask that], because there are so many structures supporting that thinking. It's like tradition; this is the role of the daughter, this is the role of the Caribbean daughter. It was a moment that just really began to shake loose a lot of the illusions and narratives and myths that are woven in all parts of our lives that we have to constantly confront, and ask it questions, and learn how to say no to it, and be really embodied when we arrive at that place of confrontation so we don't fall for the bullshit.

I want to talk to you about the body, because this was a very corporeal read for me. One of the most striking passages was when you described a dream in a letter to Gerald: “Before us, a city glints, your right nostril comes into view—a fine-etched keloid web, I touch and something is lit in me. Your irises pitch black and a mouthfeel silence where a bond used to be.” How do you approach writing the corporeal aspects of a story or a poem, especially when it's so rooted in family?

What I'm noticing is that folks are recognizing something in my skill set I'm doing intuitively, so I'm trying to figure out how to articulate it. Number one, that passage you read, that's an example of one of the dear Gerald poems coming into Who’s Your Daddy. A lot of that happened. And that was actually a dream. When I have dreams like that, they're so etched in the body. It's a visual texture and it imprints, and I have to figure out the wordscore that approximates it. I say wordscore because I want to emphasize the music and the sonics and the resonance that has to match the original imprint. I'm trying to also honor what I saw. When I'm translating a dream, I'm using language and its musicality to cast it back up again for the reader. So, I'm paying attention to sound, but an inner listening of sound, you know? It's like, we have the word insight but we don't have insound. It’s a similar thing.

The queerness of the book is also very rooted in the body, but beyond that, it was also conflict in your queer relationships that in part spurred you to reflect on love and relationships and how Gerald influenced your approach to them. In what ways do you think queerness as an identity or as an ethos informs how you approach this self-understanding, and maybe also how you approached Gerald?

I'm one of seven, and my mom is one of seven, but a lot of folks would think that I was an only child. And it's because of the quality that I have to be singular but multiple at the same time. So, I think in that way, I've always been on this angle, and that angle has created an optic for me, which I translate to be as poetic. So, when I realized that I could call myself a poet, that felt like the most queer thing. Like recognizing my creative energy and the ability to absorb and be sensitive and then move people, I believed that was something strange.

I do find some pleasure in operating from a place of defamiliarization in the way in which I occupy my body. I'm a tall, Black woman and when people meet me they expect some level of aggression, and then they have my voice. Or they'll meet my voice first and then they arrive at my body and there's always this sense of surprise. I think even, too, the lineage of Black feminist thought, growing up in a family where I had the presence of an aunt who was out and visible and would have her lesbian friends around, and a sister who has developmental disabilities and she is so extroverted. She would just go up to folks and speak in her own talk and I would translate those sounds to, “She wants a Charms blowpop or Laffy Taffy.” That boldness from her was inspiring as well as terrifying for me, but that terror was also intriguing. And my mom was a Rastafarian during my early years. Like me, her and my stepdad were weird and strange and vegetarian, and had dreadlocks in the '80s when it wasn't cool. Black folks, and my family included, shook their heads at us.

In that regard, I've been occupying the edges and the margins. If Gerald was a stranger to me, I was a queer. More than identity, queer is an action, a location. It's a constant paying attention to the ways in which things shift and change and connect, and being able to create with that, make it usable. And to then use it for ourselves, to go deep and begin to uncover where it hurts and where it shines. Doing the work of uncovering, asking deep questions, and being willing to be more and more vulnerable until you start to bloom for yourself. Not needing to hide behind degrees and identities and the roles we play so we can function in the machine. Those things are like narratives too. They are narratives that we tell ourselves, that are told to us. And we need to break them every time. And as a poet, the breaking is creative—arranging it again and again so I can feel it in the body. I think without poetry, we can't make our way out of rhetoric. Poetry reminds us that language is material and it's operating all of the time for an intention and a purpose and a meaning. It is not innocent.

There’s a line where you refer to your memory as “musk and incense,” which evokes something ethereal, scented, but not really tangible. How did you work with memory in this book, your own and others’?

I'm working with it creatively and poetically, and definitely taking my poetic license with things. I’m also learning how to identify the energy of certain words and images so that I can make these things resonate throughout the book. So that was another element with thinking about memory, the glimpses of it, the way it shimmers, memory as being, a star within our (personal) constellations. To make it look like a thing, it’s going to require a living body with their own imagination to construct it.

The last section of the book was essentially the inspiration for Who's Your Daddy. Once I had the travel notebooks, I had letters from people, the work was broadening, expanding. I was thinking about how to do more. I was in residence at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco and I was there with the art and I was noticing the royal blue, the cobalt blue, blue as water, river, blue as royalty. That started to trigger memories about the blue door that I stood behind as a little kid hiding from Gerald, and then leaping to Guyana, its translation being “the land of many waters.”

I started to write Who’s Your Daddy in this prose citation style because I needed to accumulate voices to make sense of this journey as well as this absence, and what it means to think about myself as absent-of. Then to train my brain to essentially think of presence. It's interesting creatively when you're working on something for a long period of time, you notice the ways in which we center our absence. It is like we're creating these holes in ourselves. The trip to Guyana, being in this museum, a visual space, while the writing was all coming together taught me how to go backwards and also how to go forward. I started to think about memories connected to blue.

My mom told me this weird dream she had when I was in Guyana, about Gerald, in this royal blue suit and “mashing down the back of his shoes.” It was perfect how things started to fall in place. It felt like an affirmation for being more present in my self, in my origins, embracing my many parts, and allowing myself to play. And because I played, I took some bold creative risks in Who’s Your Daddy: I have an orange bird guiding the narrator to a star ceremony by the Atlantic, all which is orchestrated by the force of my bleeding uterus. It's so many things like that, but it was just the truth of me and I think those are the most queer elements in the book.

Towards the end of the book, you touch on this question that I think is an existential question for a lot of people, maybe all people: What if no meaning is made? What meaning do you make with, or of, this book? How do you embrace that inevitable mystery of life that keeps us from making meaning of everything we might want to make meaning of?

I don't have a problem with that because I use it creatively. I don't want it to go away. I feel that each book teaches me something craft-wise, makes me a braver poet, and sometimes a braver person in my dynamics with other people. It also softens me. It's a softening in that way that comes with time and age and having to put something out in the world after much rigor—physical, emotional, and financial—everything’s put to it. So I think it just leaves me with feeling like, art is so necessary and what do people do who don't have this, who don't put their creative energy to use?