The darkness was velvet. The darkness was iron. The darkness was thin and green-tinged. The darkness was total. Never had I seen so many shades of night as when I moved to Berlin. The darkness had made me fall in love with it years before, as I gazed down from a plane into patches of utter black below. That so much night could exist within a city, flooding the side-streets and massing in secluded courtyards, entranced me.

In the complete sightlessness of the stairwell, I groped the flaking walls ineffectually, not able to see how far up or down the building stretched. Abandoning my heavy suitcase, I peered into nothingness. As my eyes adjusted, a pinprick of orange light appeared ahead of me. I fumbled towards it, hitting my shin painfully on something unseen and flailing to stop myself falling face first, as distant footfall resounded several floors above. I panicked, swatting at the pinprick. I found myself bathed in dingy, golden light when it turned out to be a switch. High ceilings stretched above me, encrusted with mouldings of flowers and faces, while garlands, angels, and Ionic columns flocked the dirty, peeling walls. Lugging my case carefully past the stray bicycle I’d just collided with, I noticed the stairs beneath me were painted a strange, dark oxblood. The walls were daubed with graffiti, including a full-breasted mermaid drawn in black marker, emerging from the waves to blow her apocalyptic trumpet.

Reaching the fifth and final floor at last, I slammed the light again as the bulb above started to flicker. The label on the first buzzer I looked at was blank but opposite that I found my friend Sara’s surname. As I turned the key in the lock and tumbled over the threshold, Melody texted me:

Hey, glad you got through Border Control ok, welcome to Germany. I know you already got tested but I’d be more comfortable if you stuck to the quarantine for fourteen days before we see each other. Thanks <3

I sat at the kitchen table and ate my now-cold airport sandwich, scrolling listlessly through dreary memes and pondering using German Duolingo again. The last time I’d tried it, the app had forced me to say ‘I want a dog’ five times in a row—‘Ich will einen Hund’—then locked me out for four hours after I’d made repeated errors because it hadn’t explained how grammatical cases worked. From my pocket, I pulled out a stone I’d brought with me from England, turning the smooth surface over and over in the palm of my hand. The friend I’d found it with on Hastings beach had told me of the local superstition, that taking one meant you must always come back.

The radiators hissed and clunked as I went around the apartment turning them on, the parquet floor still cold beneath my feet. Sara had left some condiments in the fridge for me, along with a warning that she had stored a small amount of liquid LSD somewhere inside; when I looked it wasn’t clear which container it was in. I would have to leave the apartment tomorrow and buy food, though I wasn’t wholly sure whether this was allowed. At the airport, I had presented my papers to the border officials who had barely glanced at them, despite my worried phone calls to the German Embassy, the airline, and even the airport about how to time my test, all of whom had given different answers as to whether my results would be valid for entry.

As I had wheeled my way through the dinky airport’s 1970s-era décor to the bus station, I could not help but think that my family’s brief period of rootedness, of complacency in one country stretching back to my great-grandfather, had been broken by my departure. At least this time exile had not come at the point of a spear or the barrel of a gun, but instead a gradual sickening unease about the island I had once called home. Perhaps the role of perpetual stranger was my true inheritance, as it had been for my forebears.

The apartment was beautiful, with sea green walls, brimming bookshelves, and what looked to be the remains of an old wood furnace which had been transformed into a quirky display cabinet. The television was covered by a black lace widow’s veil, and the plants I had been instructed to water were already dead. The bathroom—so narrow I could not turn around without bumping my elbows—was covered floor to ceiling in blue and white willow-pattern tiles, culminating in a raised shower at the far end that looked like a platform for some obscure sacrifice.

On the way to the apartment, I had been instructed to go for a second test at the near-empty Berlin Hauptbahnhof, just to be sure. A small number of trains were still departing from its lower levels, pigeons flying gaily every which way inside the cavernous expanse. In a side room that took me half an hour to find, soldiers in uniform checked my passport again and instructed me to stand on the yellow painted line while I was swabbed. Now, looking at my reflection in the bathroom mirror, I wondered whether the soldiers’ evident wariness was not unconnected with my shaved head and the little star that dangled on a chain around my neck.

Settling myself in Sara’s unfamiliar bedroom, I couldn’t shake the thought that there was something more to do. Eventually I slept and woke up lost and turbulently confused as to when it was, and where and who I might be. The door between the bedroom and corridor had opened in the night, letting in a cold draft that cricked my neck painfully the next morning. I donned my winter coat, found the sturdy FFP2 mask an exasperated flight attendant had pressed upon me after it turned out my cloth one was insufficient for Germany, and traipsed out onto the street in search of morning coffee. It was a cold, crisp day and the street was full of mothers with bright-hatted children in prams and schoolgirls talking excitedly in Turkish to one another. The road was clear of leaves but strewn with abandoned fridges and a stained mattress that leant against an old campervan. The mattress bore the phrase ‘Heliocentrism is a lie’ in spray paint.

I stood outside the bakery for a moment, trying to inhale as much of its delicious aroma as I could through my mask, before I went inside and bought myself a black coffee and a borek, its warm golden crust quickly dappling the paper bag with oil. Earlier, I had received a text message in a jumbled mixture of German and English instructing me to stay indoors, and not knowing much about how Bluetooth really worked or whether I would be tracked and punished if the second test unexpectedly turned out to be positive, I had left my phone back at the apartment. This had necessitated a complicated, but friendly mime routine in the bakery and the use of a small pocket calculator to indicate what I owed. Not sure if I was allowed to stand outside and devour my borek, I wandered on in search of a park bench. I came to a large and busy road that I thought I half-recognized from my walk the night before, and glimpsed beyond it the beginnings of what I was fairly sure was Tempelhofer Feld, a former airfield adapted into a giant park where I had spent several happily beer-sodden evenings with Sara and her friends many years ago.

Turning off the main road and walking down the gravelly path towards Tempelhofer Feld through another smaller park, I dodged the cyclists that whizzed past me. I tried to take in all the intricate designs spray-painted along the wall to my left, and to my right, the scattered few people walking their dogs or huddled together for warmth because they had nowhere else to go. I was surprised to see weathered gravestones breaking the winter-bitten grass in places, and white-fronted apartment blocks that loomed high over the main park. Two tall concrete towers set off at a diagonal from one another blocked the path ahead of me. Ringed by spikes, each one was topped by what looked to be a guard platform, perhaps from the days when the area had been used for transferring East German refugees to the West. Weaving past them, I wondered whether heading out onto the field might be a bad idea—Melody had said that one of her close friends cycled around the whole thing every lunchtime. What if they saw me? Was fear of being discovered the same thing as knowledge I was doing something wrong?

Next to me, an unobtrusive wooden gate in the wall creaked with the wind and I saw it was unlocked. Gently pushing it open, I walked out into a jumbled landscape of bare trees, half-finished wooden construction projects and more gravestones, some made from great hunks of polished black marble. Taking a seat on damp grass in a patch of winter sunlight, I finally rushed down the borek. I got up to wander a little further into the grounds, amazed that such a sizeable area of land had been left to run half-wild in a central part of the city. I was surrounded by trees and crumbling brick walls, and the noise of the street was muffled and seemed much further away than it really was. I walked by a large, wooden hutch informing me sternly in bilingual signage that it contained sleeping bees who were not to be disturbed. Catching sight of a charmingly rustic-looking red, brick church, I walked back over the grass towards it, noting patches of disturbed earth. The ground was thin, with clods of turf washed away by recent rain, and the dark soil beneath had pushed its way to the surface once again. In the corner of my view, I spotted something grey-white poking out from one of the patches of earth. Despite myself, I went over to it and bent down, hoping I was incorrect. But it was bone, bulbous and cracked on one side. Growing nauseous, I brushed at the sides a little with the folded borek wrapper, not wanting to touch the bone directly. Loose clumps of earth rolled away and more emerged. What the hell did I think I was doing? There was no need to try and identify this. It was a femur. In a location full of other femurs. The ground on which I stood was packed with bones, flesh, and all the assorted remnants of bodily existence. If anything, as the living one, it was I who was out of place here. Panicking, I scrunched the paper into a ball in my pocket and with my hands, began cramming the earth back over the top of the bone to conceal it from the elements again. I felt a queasy jolt as I pushed the top down by mistake and met resistance.

I hurried out of the area and back onto the path, slapping my hands together wildly to get as much dirt off as I could, before pouring water from my flask over them and wiping them frantically on an old tissue. Still breathing heavily, I slid my mask back on and retraced my steps. Opposite me at the crossing loomed a rounded, brick arch with iron gates set into it and I realised another cemetery lay beyond. Further along the road as I went in search of a supermarket, a third set of walls with the same design beckoned passersby into an abandoned cafe-terrace, with headstones thronging just beyond the tables and chairs. Perhaps this whole city was a cemetery and the living were merely interlopers, ruffling the nearby dead as we went about our small errands on the surface. With dirt still clinging to my hands, I went into the supermarket and bought only sealed items so I would not pollute any of the fresh food with the grave’s decay, looking longingly at the striped lilac aubergines, curling yellow-white peppers and teetering piles of pomegranates. After a brief confrontation during which I tried and failed to pay with a credit card, and was told off loudly but without any genuine anger by the cashier before paying with cash, I had run out of excuses to be away from the apartment and my deepening sense of solitude there. Yet the impulse to shelve myself away in a little compartment, away from disapproving eyes, grew with each step, not least because of the growing realisation that anything else I purchased would also need to be paid for in cash, which gave me a strange, untethered feeling. There was no record of anything I had bought or done, no pictures taken in this place largely without CCTV. I was still without papers saying that I could stay. I was just a pulsing, dirty, little body, in a place where I didn’t speak the language and no one knew my name.

Returning to the apartment building and mounting the staircase, I heaved the bags up with me, realisation dawning that I would have to do this climb at least once a day for as long as I was here. As I turned onto the final flight before the apartment, I heard the door opposite mine quickly slam shut. Fumbling with the key to let myself in, I had the feeling of an eye upon the back of my neck, staring intently out of the spyhole set into the centre of the neighbour’s door. I slipped inside and ran my hands under the hot tap, soaping them over and over, scrubbing vigorously under my nails with a brush, then washing the brush, then scrubbing them again until the flesh stung. I stripped off my clothes and put them immediately in the washing basket, to rid myself of any final trace of grave taint, before realising I’d touched my bag and all of the things I’d bought. I drank two shots of Sara’s too-nice Scotch, felt guiltier and took a claustrophobic shower. No messages from Melody. I thought of messaging her, but suspected she would disapprove of the whole graveyard escapade even more than I already did.

There was something profoundly erotic about all this, the command to stay indoors and hidden from all eyes but hers. I could treat these days as a beautiful, temporal cage she’d made for me, bars whittled out of care and command. No stranger to the art of denial, I could hazard that by the time we saw each other, I would be even more rabid with desire, having forgotten in ten days the feel of all human touch. Perhaps to be held apart really was to be made precious. But a former lover had once told me I was capable of having a masochistic relationship with a blank wall, transforming silence into patience, inattention into deliberate disregard, and neglect into a demand for obedience. She said she had learnt, through me, what it was like to be God. And then she had grown tired.

Assembling the food items into something resembling a meal, I sat at Sara’s low table and tried not to doomscroll. I stared out through the window, realising that the apartment looked out over a spacious courtyard, with blocks on all four sides forming an enclosed space around it. Opposite me was a looming wall of other windows, mostly dark but some brightly lit and uncurtained, allowing me to observe my new neighbours sitting down to their own suppers, watching television, getting undressed, or glumly doing home workouts. I resolved to keep the bedroom blinds down. Friends had told me about Germans’ higher level of comfort with nudity, but I had not expected it would extend beyond clubs and saunas to their own homes.

I took the remains of my meal to the living room and flicked through Sara’s shelves for a book to read. In the spirit of cultural openness, I took up a slender translated volume that detailed the travails of a friendly East German podiatrist, whose experience of life in the city was utterly unrecognisable, when compared to the steady diet of expat novels about riotous excess, underemployment, and bohemianism with which I had nourished my desire to move here. Just as I was beginning a passage in which the podiatrist soothes an oversexed octogenarian client by singing to him in Russian familiar from his days as a Socialist apparatchik, I heard a faint scratching coming from the wall, starting down low and climbing every so often. I tried to ignore it, but it kept going, getting so loud I found it impossible to concentrate. I went to examine the skirting board for mouseholes, already fearing the amount of acting that would be required to buy a trap with zero language skills. No small tail flickered out of sight and no trace of perforation was visible. The sound continued to grow louder, becoming more forceful, as if something were flapping or beating at the wall. I started to wonder whether the noise could be related to exercise or home improvement, but when it kept going without any pause or variation beyond an intensifying magnitude, I decided something must be done. Holding my key tightly as though it were a talisman, I opened the front door to squint out into the dark stairwell. Nothing was audible from this side, the sudden quiet filling me with relief, yet rendering me uncertain whether I’d heard anything at all. I rang next door’s buzzer anyway, listening to it echoing down the hallway and waiting. When no one came, I tried knocking several times.

On the floor below, an older woman in a thermal fleece came out and said something in German. When I explained apologetically that I did not speak it, she harrumphed and switched to English.

‘Why are you knocking at the door so loud? She is not here.’

‘I heard a noise … I wanted to check with her what it was.’

‘I live underneath and I hear nothing. It is the quiet hour, to make noise after ten pm is not allowed.’

‘Thank you, I didn’t…’

She was looking disapprovingly at my attire. ‘I strongly advise that you should buy some hausschuhe. Frau Cooperman has not enough carpets and your feet are very loud.’

‘What are hausschu-oh, you mean slippers, yes…’ Before I could finish the thought, she had vanished back into her own apartment. On returning, I found that the noises had stopped, and for want of anything better to do, I opened a dating app.

Pictures of lanky artists posing with monstera plants, holding borrowed dogs, and attending the sorts of parties that we didn’t know would ever come back filled my phone screen. Much of the information had clearly not been updated in some time. ‘Loves: negronis, deep conversation, bouldering and free hugs’, ‘let’s go to a rave get sweaty and see if we click’, ‘model, DJ and swamp creature, Berlin/LA/ NY’. I wondered how many of these profiles were now permanently inactive, despite my swiping, and of those how many might be dead. Then I remembered that death had not been distributed equally across different demographics. Seeing all the straight-toothed, mostly pale people with the time to go bouldering and bounce between continents, whom I had been algorithmically funnelled, made me annoyed with my own earlier carelessness. I closed the app and went to bed.

The quiet of the courtyard facing my bedroom window made it difficult to sleep, used as I was to much more intrusive city noise. When I finally drifted off, I dreamt I was pushing my way through a silent forest of glossy, green monsteras, thrusting up between the cracks of a huge and shining parquet floor. I had to be as stealthy as possible, otherwise I would be scooped up and caught. In the distance, I heard the sound of weeping and was drawn inexorably toward it, though I knew that I should run. It was a woman wailing and gasping. The weeping intensified. Someone was sobbing through the wall, right by my ear. I tried to ignore it, stubbornly attempting sleep, but it continued, louder and more ragged. Someone was in the bathroom. I could still hear them crying without a break. They were in the apartment. I shot up out of bed and raced into the corridor. The bathroom light was on. Had I done that? I pushed open the bathroom door and ripped back the shower curtain at the end. Nothing was there except an old, dried leaf. The window was closed. Shaken, I went to check the kitchen and the living room, looking behind the sofa, feeling stupid. I even flung open the wardrobe in the bedroom, finding only winter jackets. The crying had stopped and I had no choice but to settle back down, though I could not lull myself fully back to sleep. I tried to calm myself, thinking only of pleasant, repetitive things like peeling lemons in a spiral or plucking petals from a daisy, but each time my mind neared nothingness, a wet, choking glug would come from the next room, as if the crying might start again in earnest, and so all night I remained caught between wakefulness and rest.

The next day, glue-eyed over steaming coffee, I wrote to Sara and asked her about next steps. When would I hear from the test centre about my results? How would they contact me? I’d insisted on squeezing the country code for my phone onto the form and they had asked me with great disappointment whether I did not have a German number. There had been no space provided for my email address.

Sara: They aren’t going to get in contact unless you’re positive. Possibly not even then.

Me: But my registration thingy is in a few days, should I try to move it?

Sara: NO!! DO NOT MOVE IT

Me: but there’s a website, it should be easy to move

Sara: you won’t get another appointment for months, seriously do not do that you will mess up your visa

Me: Won’t I get in trouble if they find out?

Sara: They won’t know unless you show them your plane ticket. Just wear a mask and bring them the forms I filled out for you. I don’t think the different branches are allowed to talk to each other.

The various pieces of paper I would need to begin my new life stretched out ahead of me, all written in indecipherable German and with fines attached for non-compliance. Was I missing forms that I needed? Which ones? I had no idea. Every time I attempted to research my taxes or immigration status, a tidal wave of information, most of it irrelevant to my circumstances, crashed down over my head. I suspected that trying to begin the process in a more normal time would be even worse, the demands of day-to-day life jostling with the slow and frightening churn of alien bureaucracy.

Life in Sara’s apartment continued, following much the same pattern. Each day, taking one of my directionless walks, avoiding the concealed graveyard to explore other parts of the neighbourhood. Each night, nervously sleeping, hoping not to hear the weeping, although I often did. I began leaving the light on in the bathroom pre-emptively, so I did not have to ask myself whether I had really been the one to flick the switch. My new favourite spot nearby was a long, sunken garden, complete with stone fountains, a gravelly terrace, and grand staircases sprawling down from street level. I made a daily circuit along its rectangle of damp, patchy grass amongst the horde of enormous, grey corvids which were not exactly magpies, but not crows either. Many of the surrounding streets were dotted with dark, bronze memorial stones, rising partway above the level of the pavement, catching at the feet of passers-by. I tried to stop and read each one, imagining the myriad lives each person or family might have led before they had been shrunken down to ash and soap and bone and transformed into these little metal blocks. One morning, I was walking along a side street and saw a man on his hands and knees over one of these stumbling stones. My first fear was that he was defacing it. I considered running over to kick him in the head. But on closer inspection, I saw that he held a sponge.

My registration appointment was scheduled at a branch of the Berlin residency administration far out in the Northwest, requiring me to take several trains and then walk a tree-lined street in what appeared to be an entirely different city to the one I’d thought I was moving to. There were white-painted villas with romantic balconies, ancient-looking houses formed of one steep triangle, roofs pointing skyward, and at last what looked to be a small stone fortress, which Maps advised me contained the Bürgeramt. Inside, I passed through a series of low-ceilinged beige rooms to a waiting area where I sat, anxiously checking the numeric code I’d been given against the gnomic strings of numbers appearing and disappearing on an old television screen. Mine eventually appeared and I scurried to room 23a, sweaty in the skirt suit I’d crammed myself into that morning, with no idea of what to expect. I slid a piece of paper across the desk to the kindly-seeming civil servant, advising him that I did not speak German and waited, trembling. He stamped my registration form with a blue ink seal depicting a little bear and said in English ‘welcome to Berlin’, before advising me that I was free to leave.

Steps light, heart buoyed by the prospect of having proven that I was indeed living in Germany before the axe came down to sever my stubborn island nation from the rest of Europe, I made the trek back to Sara’s apartment and bounded up the stairs. I would start taking German classes! Next week, I would open a bank account! I would get a German phone contract! Tomorrow, I would start looking for a flat of my own!

At the top of the stairs stood a pale, dark-eyed girl about my age, presumably my noisy next-door neighbour. Before she could open her door and disappear again behind it, I shouted ‘Hey!’

‘Hallo?’ She evidently thought better of retreating now that I had engaged her and I decided to press my advantage. ‘Do you speak English?’

I noticed without being able to help myself that she was very pretty, sable curls and arched eyebrows bold against her pale olive skin. Her clothes were dirty and frayed, and I wondered whether I had interrupted her in the middle of her work.

‘Little.’ She made a pinching gesture with her finger and thumb, passing her gaze over my outfit with evident curiosity. I slid down the mask so she could see the movements of my mouth.

‘Is it you making all the noises at night? It’s okay if you are, but I want to know where it’s coming from.’

‘Sorry … I do not understand you.’ She cocked her head slightly, her eyes fixed on mine. I mimed knocking at the wall for her ‘Do you make noise?’

She asked ‘Do you hide too?’

‘A little bit.’ Her gaze slid down over my neck, flicking on downward to where my shirt strained at my breasts.

Meeting her dark eyes, I felt the rushing sensation of new desire, mingling with a sense of recognition and a curious undercurrent of fear. But I tended to like women who made me a little afraid.

‘I can come in?’ She looked hopefully at my door. Could I press my advantage here? I saw the way she looked at me and what she wanted; it would be a grand thing to have a lover right across the hall. Melody had always disdained the strictures of monogamy, and I had never asked who else she saw. I considered the inferno of probable consequences if the two crossed paths, peering down into the stairwell as if I already heard her coming up.

‘Sorry, not allowed. Maybe later?’ I arranged my features so she could see that I was genuinely disappointed at having to refuse.

She nodded and smiled thinly. ‘I will quiet.’ She waited, watching as I unlocked the door and closed it behind me, reuniting with my loneliness.

I prepared and ate another solitary supper, briefly unveiling the television to see if there was anything terrestrial I could stand to puzzle my way through, but quickly found that there was not. No further sounds came from the wall and I was filled with relief that my new neighbour had kept her promise. No text from Melody either, though I saw from social media she had been hanging out baking bread with one of her friends indoors, with whom she was presumably in a pod. I had already messaged Sara earlier that day and knew no one else in the city to reach out to. I didn’t want to write any of my friends back home because it would mean admitting where I was, and I still feared the possibility that I would be sent back there with my tail between my legs for some unforeseen infraction. I poured myself a big tumbler of Sara’s whisky and looked up the bottle online, swearing to myself I would replace it as soon as I knew when I was leaving. The whisky was wonderfully peaty, the taste of smoke and leather unfurling on my tongue. It hit me harder and faster than I’d expected and I tumbled into bed, this time shutting off all the lights and stripping naked, hoping that I would quickly drift off into a happy stupor.

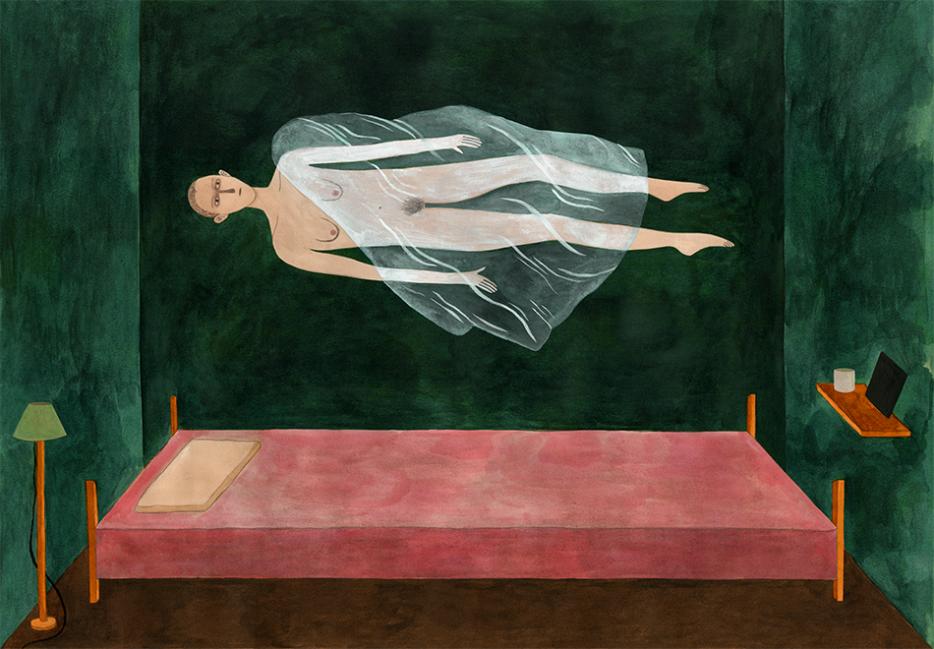

The clean, soft sheets draped half away from my body and a pleasant breeze blew across the exposed skin in little eddies, playing over my neck and chest. I relaxed into the dark bed, spreading out to find just the right position—legs stretched and sheets taut—as I kept my eyes closed, trying to nuzzle my way into oblivion. Feather-light gusts tickled the outsides of my ears, lips, and down to my outstretched foot as I felt the sheets begin to chafe, but not unpleasantly, at the most sensitive places on my body. Despite my decision to ignore it, pressure built as the linen enveloped me, flowing feather-light across the surface of my skin, or binding me tight with delicious friction that built with steady urgency. Breaths that came as strong as fingers caressed me, travelling the length of me, beginning to tease and probe. Slowly, I felt as if drawn aloft with invisible pleasure, floating up weightlessly toward the ceiling. I was laid bare yet enveloped, supported yet free, the speed of the breath’s strokes intensifying as I told myself this was still a dream. Unable to move my wrists to brush away the delicious sensation nor strain my ankles to kick myself awake, I gave in and let the pleasure build, a firm, sure touch rippling my flesh almost to crescendo, when I felt ever more distinctly two cold lips inching up my throat, searching for my open mouth. As much as I wanted to surrender entirely to sensation, each icy kiss increased my terror of what the final consummation must entail. I plummeted back down to the mattress retching, vision overlaid with decrepit decay from a brief second that I’d opened my eyes.

I fumbled to the brightly lit bathroom to splash my face and neck with water, still wheezing and fearful a look in the mirror would confirm that I might not be alone. The chill air of the apartment was thick with another sorrow quite distinct from mine. It was so hungry and overwhelming that fear mingled with my guilt at pushing away my spectral visitor—she had longed to take me somewhere I knew I must not follow. Or at least, not yet. Shivering, I hunted for a robe to pull around me, and in the corner saw my trousers protruding from the laundry basket. Immediately I was struck by a sudden, terrible thought. I dug in the pocket for the borek paper and found it still scrunched tightly within, wrapped around a clod of earth and a tiny splinter of greyish bone.

Pink and groggy from fighting the return of sleep, I hurried to dress against the winter cold of dawn. The street was entirely empty, the pavements rimed with frost and the wind biting at my cheeks as it blew down the long, straight road. Stumbling back through the low gate, I searched among the headstones and hillocks until I found the right patch of disturbed soil, looking all the while over my shoulder in case I was called upon to explain myself. Digging with one finger in the dirt, I plumbed a hole of about the right depth and, shaking out the pastry packet, gently returned the lost fragment to the rest of the remains below. I stroked the damp, crumbling surface to smooth over the top, and read the Mourner’s Kaddish aloud from my phone, hoping but not knowing whether this alone would be enough to keep her there. Lips still tingling with cold, I begged her silently to rest now and let me sleep, before I turned my little stone in my fingers one last time, and set it down to mark the spot.

Beyond the gate, out on the field, I left the graveyard to walk alone for a while, beneath a vast and empty sky.