The original title for Scaachi Koul’s Sucker Punch (Knopf Canada), the follow-up to her bestselling 2017 essay collection, One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter, was a translation of a Kashmiri phrase her mother would often hurl in exasperation at Koul and her brother whenever they acted up as children. “Paye thraat.” I Hope Lightning Falls on You.

“My mother didn’t mean it, nor did she ever mean any of the unkind things she would say to me throughout my life,” she writes in her second book. “She was merely the type of woman who said how she felt when she felt it.”

I know this exasperation. I know it through the phrase my own mother had for it when I was a child: ¡Que coraje! In other words, “what a pain,” and in fewer words, “UGH!!” But like Koul, I don’t remember feeling fear or shame on hearing those words. What I remember is a quick way to communicate annoyance, better expressed and resolved, even if imperfectly, than unaddressed and built up over time.

In the years since beginning to write her second memoir in essays, a lot has happened in Koul’s life. The world locked down for COVID, she lost her job, her mother’s health declined swiftly, and her marriage fell apart. Its dissolution circles every other memory and argument in Sucker Punch. There is a difference, Koul outlines, between argument as a means of progress, even intimacy, and getting stuck in a harmful cycle that achieves neither. I spoke with Koul in mid-March about how to discern the difference, and how to let go.

Chantal Braganza: You discuss, in the last quarter of the book, that the act of writing it began to feel impossible—that the structure of narrative felt removed from your life after having all these plans blow up in your face. When did you know this second book was possible? When did narrative return?

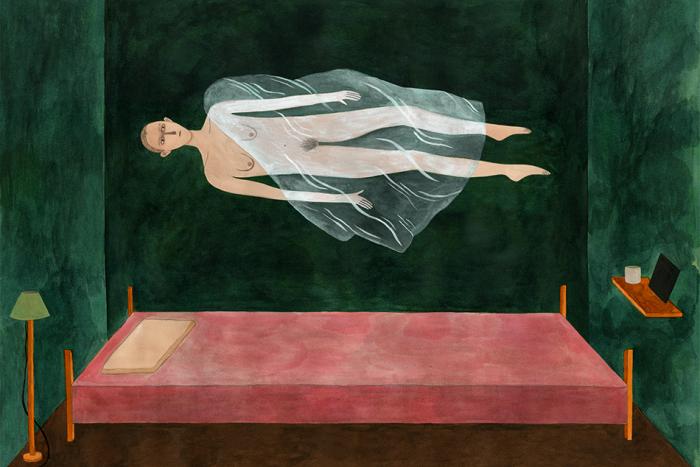

Scaachi Koul: At the very end. The last thing I did to the book was put in the structure of reincarnation. That’s when I was like, oh I got it. But that was the end; the whole time I kept thinking it read well, but that it felt nebulous. Like I couldn’t get it under control.

Having this framework of reincarnation drawn from Hinduism, which you describe as a constant presence in your life, how did it feel to have it play such a strong role in organizing the book?

My feelings about religion have changed, broadly speaking. I’ve relinquished myself much more to inevitabilities. It doesn’t mean that I don’t fight anymore. There’s lots I know I can do in my own life, and in other people’s lives. I recognize that. But I also see more now that a lot of it is futile! Things are going to happen anyway and they’re going to happen the way they’re supposed to happen. That’s freeing in a lot of ways, because it means I’m not going to have a lot of regrets.

I also think I am much more acquiescent to life cycles. I accept change a little more readily because I now see at my, uh, very advanced age that I will end up in the same place again. It will happen. If I have unfinished business with someone, somewhere, in some place, I’ll get there again. I try not to lose sleep over it anymore. I still do. And I still try.

What’s your criteria now for what’s worth a fight?

I haven’t had a good fight with anybody in a while! I wish I could say I’m always in control of it.

I’ll always fight with my parents. I think I’m biologically incapable of not doing that. I’ll fight with a friend. I’ll fight with someone I know.

I think I’m less inclined to fight with strangers. That’s a newer advancement in my programming. I did that a lot before, which I think was instructive and helped in some sense with whatever discourse I was contributing to. But I just don’t feel like it anymore. I just don’t want to. I think the political landscape has changed, the internet has changed, Twitter has changed. It’s just not the same anymore. My contribution feels different.

This might be conjecture on my part, but the change in the title of the book to Sucker Punch feels like it reflects the shift in your attitude to conflict in the book.

Yeah. I Hope Lightning Falls on You—that was maybe the second or third title I had. This book was under contract for almost seven years, and that original title was mostly about my mom.

It just didn’t make sense for what the collection eventually turned into. When my mom is saying that to me, there’s a lot of intimacy and kindness in it. It’s a very specific kind of language that brown people and immigrants speak. To us, there isn’t violence in that. When she’d say that, I wasn’t afraid of her. I’d be like, alright girl.

But then when I was thinking of squaring that away with stories about my divorce and sexual assault, it didn’t make sense. There is harm in those things. Weirdly enough, it felt like there was too much levity in Lightning.

But then! My fucking book editor’s husband, like literally my nemesis, I’m on the phone with her and we’re trying to figure out what it could be and from the kitchen he’s like “What about Sucker Punch?” I’ve never wanted to kill a man more in my life. It is with pure rage that I have to give a man, married to my friend, credit for the title.

But yeah: Lightning, as a title, was from when I was writing about my family. Sucker Punch is about having plans, then the shock of having them all blow up in your face.

You need to read this book sequentially to get its full effect, but I love how the fact of divorce hangs over most of the book and the details of it are omnipresent, rather than it being described as a linear event. And then there’s a particular moment at the end of the book—an argument that feels like it is an event.

I pretty firmly keep people at arm’s length; people think I don’t, but this is maybe 25 per cent of what happened. It’s not a fulsome story. There’s way more I can say. In thinking about it narratively, and asking myself if I wanted to take you to the last day [of my marriage]—it made sense. The energy of that conversation is hanging over the entirety of the book.

Years and years ago, I was working on the book and couldn't get anything done and every word I came up with was garbage. And I’d send them to my editor who’d respond very kindly, “This isn’t it.”

So, I spent a weekend holed away. I was still married, it was mid-pandemic, and I was tucked away with my laptop. I wrote like 25,000 words in two and a half days. I don’t know if it was good! I was trying to put anything down. I figured I’d read it on Monday and see if it was anything I could send to my editor. When I opened it back up, my laptop had completely crashed. I don’t know what happened. It just ate itself.

When I got it repaired, it had deleted everything I’d written that weekend except for the first 3,000 words, which got caught by the cloud. Everything else was gone. I wept.

It was also exactly what needed to happen. Everything else I had written was about a version of my life that no longer exists, was not going to exist, and was probably me still obfuscating the truth from myself. I was trying to figure out why I couldn’t write about conflict, when my whole life at that time was being guided by this one conflict I didn’t want to have.

It sounds like another version of choosing which fights are worth having.

Yeah!

Did you send passages of anything you wrote about people to them this time? Did any of them disagree?

I talk in the book about having done this the first time around, sending people passages for a read. But otherwise not really. I mean, I sent some to my friends: I wanted Adrian to know I was accusing him of having sex with birds. But I wasn’t ever going to take that out. I just wanted him to be aware.

But otherwise, no. I mean, who was I going to tell? The book is very interior, it’s a lot of conversations with myself. There are people in there I’m not in touch with anymore, and then there’s my family. And I love my parents, I think everybody’s parents have their versions of what happened and you have yours. What my dad loves more than anything is when fact checkers call him, because he will just tell them lies—he thinks it’s funny. I once did a This American Life segment and they have this very rigorous fact-checking process, as they should! I mentioned something about him being like 5’2” and they called him to check and he said, “I’m 5’6”.” I can’t stress this enough: my father has never been 5’6”. I’m 5’5” and I’m the tallest in my family. He thought it was so funny! They had to take the line out because they couldn’t confirm his height.

This book is truthful. I’m telling the truth and I’m speaking factually. But it isn’t a document of journalistic merit. It’s not a documentary. I’m not trying to litigate something that happened in a reporterly way. This is interior. Maybe in the next book, I’ll feel differently.