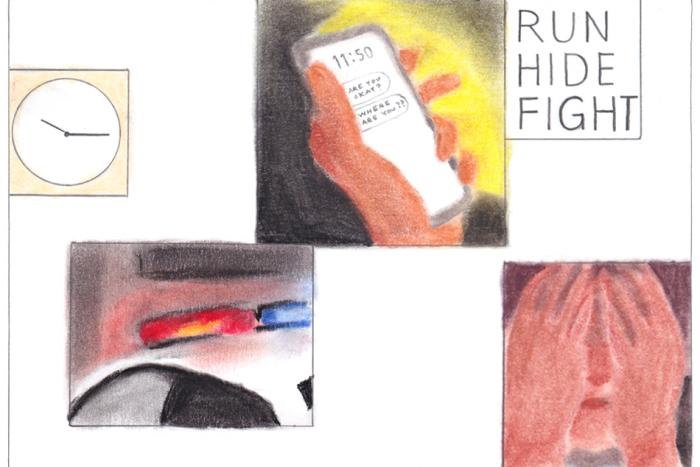

What does a campus shooting feel like?

When Wanda bought the house, she didn’t imagine that anyone in the community would recognize that she and Lynn were queer.

Latest

When Wanda bought the house, she didn’t imagine that anyone in the community would recognize that she and Lynn were queer.

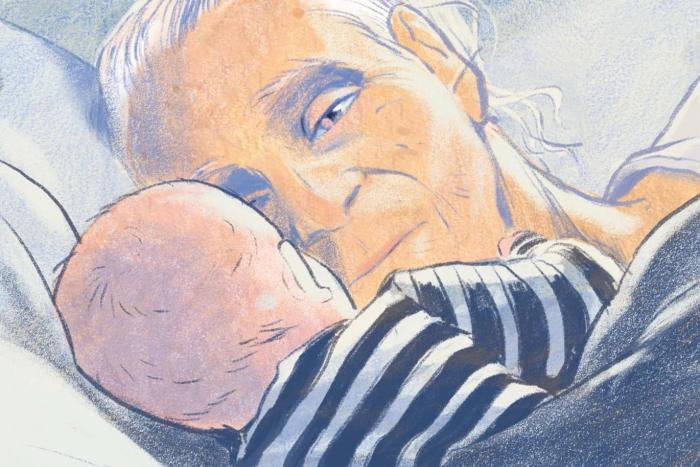

The baby had come from a place none of us could remember. Our grandmother was headed there.

The author of Mother of God discusses the limitations of realism, Frank Bidart, and the anguished duality of shame.

I worried I had broken the chatbot by trauma-dumping, and no one, human or machine, had the capacity to console me completely.

If he took a shortcut, if he made the creative process any easier for himself, the magic would be lost.

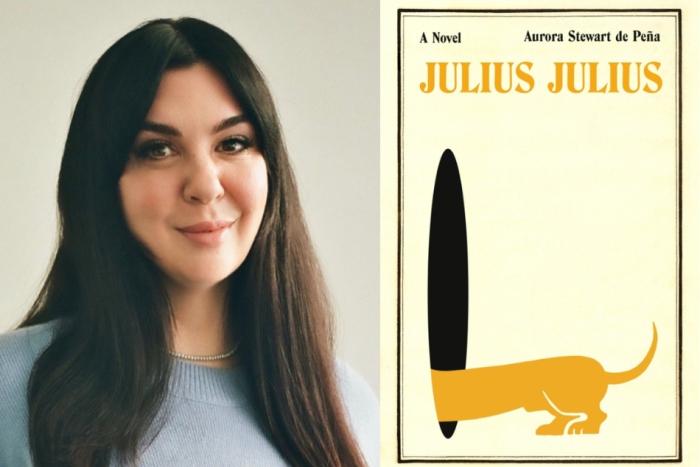

The author of Julius Julius on ad agency ghosts, shaming PSAs, and sexual harassment post-#MeToo

The manner of my demise is of little interest, besides serving as our jumping off point.