One of the first, best, and only things I read about Lou Reed on Sunday afternoon came from poet Michael Robbins. “My Lou Reed” trivialized the wave of writing about to hit us—“I know ten thousand bloggers are composing their ten thousand stories about how the Velvet Underground changed their lives, & I don’t believe rock & roll bands change people’s lives”—before sharing his story about how, when he was 16, the Velvet Underground changed his life. Reed’s legacy doesn’t need anyone to back it up with testimonials. The scope of his influence renders any single listener insignificant. Yet sharing personal stories seems a far more apt response than critical analysis.

*

My Lou Reed: I heard the Velvet Underground for the first time in 1991, when I was 13. My father was on sabbatical at Stanford, my family was living in Palo Alto, and I was getting a sense for just how badly music could get to me. I spent a lot of time with Nevermind, Bleach, Death Certificate, and We Can’t Be Stopped. Somehow I ended up with a cassette of the soundtrack from The Doors—I think my guitar teacher gave it to me as part of an assignment—and for reasons I still don’t know, “Heroin” was on there. I listened to it over and over again. Every night before bed, I’d drink a glass of milk to relax; that night, I dropped it during one of John Cale’s freak-out sections and, dazed and only partially in control, picked up the broken shards with my bare hands.

*

There’s really nothing left to say about Reed, forefather of punk, indie rock, noise-as-pop, and poet laureate of big city scuz. Writers typically salivate at the kind of thoughtful overview prompted by death, box set, reissue, documentary, or reunion. It’s a chance to think hard about the best music ever made, the stuff that’s most important to us both personally and professionally. Reed’s influence, though, is both exhaustive and overstated. He’s responsible, directly or indirectly, for much of America’s rock underground. At the same time, designating Reed as the ur-point is like saying the ocean is wet, the sort of category mistake a child or scientist might make. Eno’s famous line that “The first Velvet Underground record only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it started a band” is now a cliché, applicable to the Velvets the same way that we’re all related to Genghis Khan. A close reading of Reed’s music? It’s hard to imagine tackling his lyrics fresh when we’re already living all around them, every day.

*

In 1992, I read Charles Shaar Murray’s Crosstown Traffic, a meditation on Jimi Hendrix’s relationship to blues, jazz, funk, and pretty much everything but the hard rock he nominally played. The book not only broadened my tastes, but taught me how to think about music analytically. I hadn’t listened to the Velvet Underground since returning The Doors soundtrack (I have no idea why I didn’t dub it), and despite Murray’s multiple mentions of the solo on “I Heard Her Call My Name,” I didn’t go back to the band that year. I was headed in the other direction, away from rock; it would take another year or so before I swung back, dutifully returning after discovering indie rock through Chapel Hill bands like Superchunk and Polvo. The bands descended from them were even more chugging and textural, relations separated by space and time, in the same way that “I Heard Her Call My Name” wasn’t Ornette Coleman. They were very much of their time. Prickly, nasty, preoccupied with what lay on the other side of the spectrum. Stripped down and malignant because someone had to be.

*

Lou Reed is not the Velvet Underground. John Cale played every bit as important a role in formulating the band’s sound. Reed the solo artist made Transformer, Street Hassle, Coney Island Baby, The Blue Mask, for starters. The Velvet Underground and Nico came out nearly five decades ago. “Walk on the Wild Side” is forty years old. Nobody from Generation X can breathlessly recount the first time they heard “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” much less “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Reed made music that remains contemporary, accessible, even as its context recedes further and further. Every few years, there’s a new way to appreciate it, and we keep reaching backward as it turns up new mysteries, but it’s too late to uncover the songs’ secrets on their own terms, in and of themselves. We talk about ourselves in relation to Lou Reed because otherwise, he’s just another Baby Boomer artist. We’re the cultural currency.

*

In college, I had a friend whose father was part of the intelligence community. He may have been in the CIA. We were never sure. His father couldn’t stand hippies. He discovered the Velvet Underground. Out of sheer nihilism, he signed up for Vietnam and auditioned as a spy.

*

When I heard the news, I tweeted that, “Without Lou Reed, 50% of my life wouldn’t exist.” That’s about as confessional as you can be on Twitter.

*

I saw Reed live once, outside of Philadelphia, around the same time Animal Serenade was recorded. He played “Street Hassle,” which astounded me. I hadn’t quite realized that song, or many of Reed’s songs, could be performed outside of the confines of a room and a stereo. But they were, and it worked, and it was pretty much the same effect, despite the sharp differences in instrumentation. The thing I remember most vividly was the first time he strummed the guitar; that sound was still the same as it had been 40 years ago. It came from a human, not Gilgamesh. A guy hitting the strings as if he cared a lot, just not about the act of hitting the strings, hadn’t changed one bit.

*

There are too many things to say about Lou Reed. It’s unwieldy, unmanageable. If our instinct is to start with ourselves, maybe it’s because that’s the only way to start tracing a single path. It’s an exercise, one that’s as much about generating resonance as it is about making sense of an output that speaks for itself. Describing the music rings hollow, as does explaining its emotional center. Lou Reed’s death is a chance to take stock not of what he made, but what we did with it. Every Velvet Underground story is, out of necessity, personal—otherwise, it’s hopelessly impersonal. The smartest thing to say about Lou Reed’s legacy is to admit how stupid his art may have made you over the years. If that’s changed over time, you can thank him for that, too. That quality has been in the music since the day it was released.

*

Two years ago, my daughter was born with “What Goes On” playing. If “Heroin” is frightened and frightening, “What Goes On” is the perfect statement of ambivalence, a happy song that’s lost, a sad song that’s jaunty. It’s giddy, animated stasis, something altogether different from the irony or apathy often attributed to Reed. I’d say that’s progress. I can’t tell you yet whether it’s the definitive statement on human existence—the perfect note to start a life on—but it sure felt right at the time.

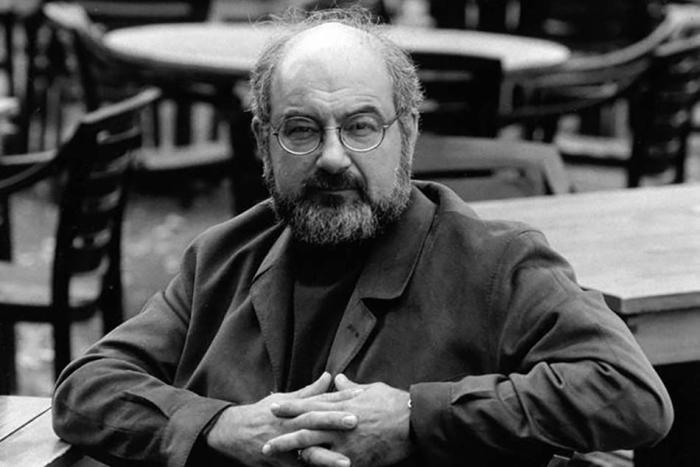

Bethlehem Shoals is a writer living in Portland. He's a co-founder of FreeDarko and The Classical. Follow him on Twitter at @freedarko.