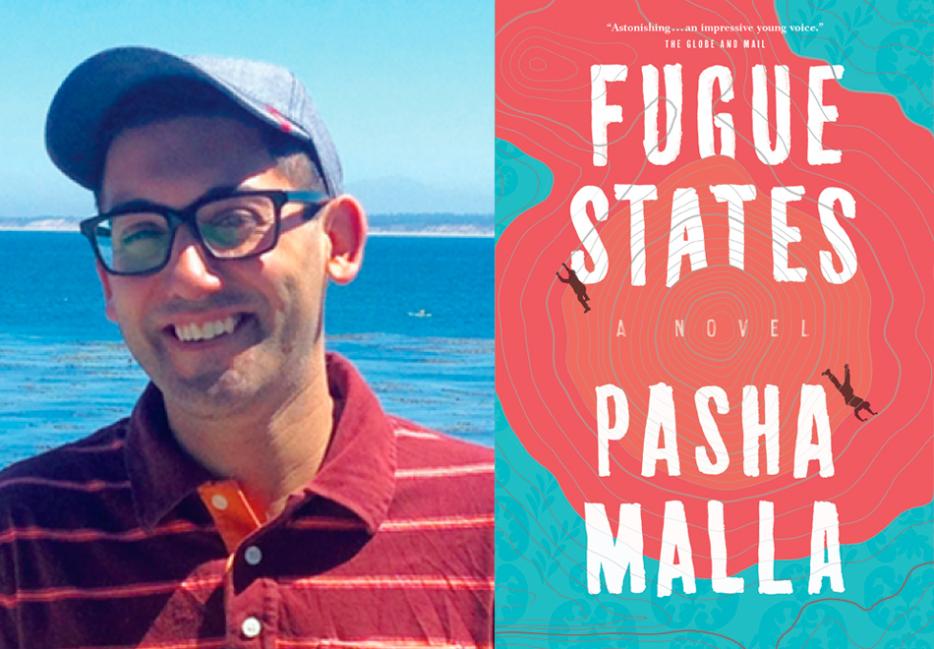

I first saw Pasha Malla speak in 2008, at a packed event at the Gladstone Hotel in Toronto, for the launch of his debut collection of stories, The Withdrawal Method. Instead of a customary reading he presented a slideshow which included a series of doodles he made as a kid in London, Ontario while fascinated by the Nazis: swastikas, guns, fighter jets and tanks. Each drawing was accompanied by self-lacerating commentary on his childhood psychology, and if I remember correctly, he didn’t read a single story from his book that night.

This lite deviancy left me enthralled at 21—who was this funny brown dude treating his own book launch with irreverence? I scooped up the stories and was engrossed with the tender rage he presented in the collection: brothers full of love unable to talk to each other, absurd imagery that stretched and collapsed. The book was funny. Like, funny-funny, but then the stories would detonate in unexpected ways and leave me reeling; it seemed impossible that someone could make stories twist and feel with such precision.

Since The Withdrawal Method Malla has published a collection of poetry, found poetry focusing on post-game interviews with athletes, an art book riffing on Frank Capra’s Why We Fight, and an experimental novel, People Park. He has taught at the University of Toronto and mentored a wide range of authors, alongside writing a regular books column for The Globe and Mail, and contributing regularly to The Walrus, Newyorker.com and others.

Last year I was fortunate enough to work with Malla on a project of my own. I was a little scared to meet someone I knew only through their work and my own admiration, but my fear was needless. Malla greeted my writing and me with a relentless generosity, rigor, and seriousness. While I spent the summer floundering with the state of my own work, ambition, and relationships, Malla—unbeknownst to him—provided a kind of anchor and model of what it meant to live a life in the arts, one built on dedication to serious thinking and a devotion to craft free of pretension.

His new novel Fugue States (Knopf Canada) follows Ash Dhar, a thirty something radio interviewer and author, spiraling outwards from the recent death of his father. The book is ambitious in its scope—at once a comic farce, serious in its psychological searching, while also delicately taking apart the conventions of the realist novel. It manages to be a page turner and provocative simultaneously, asking from the reader as much as it gives.

We talked over Skype; Pasha in his book adorned office in Hamilton, Ontario, me in my balmy room in Toronto. He laughs often when talking about basketball or something personal but shifts gears quick when speaking on writing. We were interrupted only once, near the end, when his big bushy dog burst into view. We spoke mostly about Fugue States, how it came to be, and the responsibilities he felt towards it and by the end of the interview he was back to recommending me books for my own work.

Adnan Khan: What was the process to get into Fugue States? One of the things that’s curious to me is that this is very much a realist novel, but at the same time there are some elements of it that feel like you’re poking at the genre a little bit.

Pasha Malla: Oh yeah, totally. The intention is that it dismantles the whole structure as it goes.

I think I set out to write a realist novel and then what I wanted to write about and talk about kind of required me to disobey the conventions. It’s so weird, I started writing this thing six or seven years ago, and you have to try to remember where it started. And I don’t know. I mean, I’ve been saying things…I dunno if any one of them is true or it’s a combination or I don’t know.

I was just interested in trying to write a realist novel that was about a chronological story that takes place in space and time, where, you know, people do things that people do.

To me it seems like the easy sell for this novel is that it’s a comic, Diaspora psychological realism novel, and then as you read it, you see it sort of turn inside out. I’m curious to know why you did that, basically.

Lots of reasons. I mean there are reasons of my own accountability to the material. Like, I don’t feel like I’m the guy to write a novel of Kashmir, you know? Those aren’t my stories to tell, there are already plenty of writers who are writing about that place, better than I can, people who live there, people who speak the language, people who are on the ground getting shot in the face with pellets and shit like that. So, yeah, I did not, I really wanted to, not take that one. Not appropriate it, I guess.

At the same time, I thought that there was something interesting in that tension of having this tenuous cultural heritage, from this place, being a piece of who I am, and so actively resisting it for ten years of having a writing career, because of that concern. Because of that concern and because of how that shit gets commodified and how in some ways writing about it is adhering to a market expectation and how easily that becomes packaged.

It’s interesting that you say that—to explore that tension—because re-reading The Withdrawal Method, there are a few stories where there are certainly brown characters, but it’s not central to the story. Someone asked you in an interview why in The Slough, the first story of The Withdrawal Method, you named a character Pasha, and you talked about responsibility and not wanting the character to get away with something. The Slough is almost a foreshadowing of this novel, in the way that story also inverts upon itself.

The point of that inversion was more exclusively literary and the points of the inversion in this book are, for lack of a better word, political. Or at least, I’m trying to—by sort of dismantling the structure and by setting up one kind of story only to subvert it I hope that I am—asking some questions about how we create narratives: political narratives vs. narratives of masculinity vs. narratives of purpose.

One of the things that came up was this idea of responsibility. It seemed to me very much about responsibility, about whom is responsible for whom and not just who cares for who—but who is responsible, that sense of duty.

Yeah, duty is—I mean, dharma.

And it comes up in The Withdrawal Method, there are at least two stories about care giving and that sense of duty. I’m also curious to know, because the Kashmiri question comes up, there’s a point where Ash directly addresses this—when he discovers his father’s manuscript, he asks something like “why would I write this book, is it my story to tell?”

He says explicitly that the character had written this kind of silly book and then felt the weight of doing something political, and wanted to write about Kashmir and then just couldn’t find a way in and felt disingenuous or manipulative or in some way advantageous to his own career to write about a very serious trauma.

Is that cynical? Maybe I’m being cynical, maybe I’m being naïve, but even your willingness to engage with that question…I don’t think that if you publish this book and you take away all those questions about who can write about Kashmir, I don’t think anyone would say to you: you can’t write this. I think they would say, “You’re half Kashmiri, your father is Kashmiri, go nuts.”

I think it’s just a personal resistance—I don’t really care what other people say. It’s just a personal thing, especially having gone there with my dad and feeling so outside of that culture. I went while I was writing the book. Basically I’d written drafts of the first two sections and I was like, “Okay, well, I’ll go there with him and then I’ll be able to write the third part where they actually go” and it did not go how I was expecting. I did not come away from that trip with any sort of better understanding of the things that I wanted to write about but a whole different set of questions that I thought were worth pursuing.

What did you go there wanting to pursue?

I thought I would just go there and get some answers. Just see the place and breathe the air and some way innately understand it. I hadn’t been there since I was four and I have no memories, or very, very small little flashes of sensory memory of ever being there.

I thought, yeah, I had expectations of that trip, that it would sort of be like a birthright trip or a homecoming or something and I would suddenly be within my people. It was, like, not like that, at all.

It’s a decimated place. It’s really not what it once was. Infrastructure is crumbling, people are suffering, the large proportion of the population no longer lives there, and 40,000—probably more than that—people have been murdered. It has kind of a shell shocked feeling of a place. It’s still beautiful if you look up, but if you look down, it’s degradation. And it’s not what it once was—at least, what I’d been told what it was.

The story then became about the idealization of what it is to people, to exiles, and how the place can never be what people want it to be, or how it’s remembered. They remember in this idealized sort of way.

I think that the character in the book, Ash, has inherited this idealized version of what that place will be and has this innate suspicion that it is not that so I think he knows that if he starts to write about it, he will be writing about a false version, and then, he resists going because he doesn’t want to know the truth, and then he gets there and forgets why he’s there!

Why is care giving, or duty, so prevalent in your work? Ash does go to India for Matt—there’s an underlying sense of taking care.

When I was writing The Withdrawal Method my step-mom was really sick and my dad just dedicated his life to taking care of her. I mean, he talked about dharma all the time—it’s like, I’m not doing anything good, I’m just doing what has to be done. Not out of obligation—but this is what you do. And, you know, I like that idea.

I like to think about the various degrees of loyalty and what that means in friendships and how Matt’s idea of loyalty is built into this code of what he imagines it means to be a man and a friend and whatever else, that the book kind of dismantles. And I think that, you know, ways that men in this novel, like Chip is the sole caretaker for his son, who has cerebral palsy, and it’s just a relationship that Ash cannot fathom.

I wanted that relationship to have an irony to it, where we see how hard this guy is trying to take care of his kid, as a man, he’s doing his best, and there’s something kind of innate to how he’s been culturally limited to do it right—or at least, how he feels he should be doing it right. Struggling with it and whatever else. You know, you don’t read a lot of books—I don’t anyway—that apply that care-giving role to men, or caretaking. How men take care of each other and family and friends and everything else. And also how they fail.

There is this undercurrent of menace through the book; Ash’s father is very angry, Ash is morose, but then there’s this comedy throughout. Even Matt—who is this incredibly destructive force for most of the book—is quite funny.

I wanted to make their characters multivalent, so they’re not all just struggling with a kind of masculinity. Whether it’s bro culture masculinity that Matt feels like he has to live up to, or some sort of paternalistic culture the father needs to live up to, or whether the son feels like he has this male inheritance.

But the way that North American male culture is built, that sadness sharpens into anger very quickly and the way that it manifests outwardly as hostility, violence, anger, aggression, and for the three of those characters. You know, Matt is physically violent, Ash is linguistically violent.

And I think for that to work and the kind of tone I wanted—I didn’t want it to just be a book of menace, because that would create a kind of monotone that didn’t work for this. I think it works for something like Blood Meridian, where that tone is crucial to how that book operates, but I wanted for that to be not the dominant strain, but an undercurrent that is inevitable, especially when it rises up and becomes so prevalent.

It’s very unsettling. The Matt-in-India stuff is terrifying.

And he doesn’t know! I kind of wanted a certain, it’s hard to create expectations for what you want from the reader, but I liked the potential for the character—the people who find him innocuously entertaining and have some sympathy for him, I think that’s good. But I also wanted to turn that into a kind of complicity, where his bumbling is such a symptom of a certain type of privilege. And that this kind of behavior actually wreaks a lot of havoc.

I think that my intention was to try and create a character that feels potentially dangerous but is innocuous enough—at least in the first two, maybe the first part of the book and then starts to shift in the second and then really shifts in the third—that if you’re entertained by this guy, then suddenly you’re like “oh shit, I kinda got sucked up in this character.” To some people I think he might be charming, or sympathetic; and certainly some people would find him repulsive. That’s fine too.

I was also interested in the relationship between Ash and Sherene. It’s sort of set up initially that Ash is very needy towards her, and kind of longing for her, but then it comes out that it’s a friendship. You see that Sherene, a woman, is the only place where he can express that longing for intimacy. Whereas Matt, who is desperate for it from Ash, never gets it from Ash.

Yeah. And they have an intellectual intimacy. There’s nothing really romantic there. There’s a kind of longing of certain kinds of friendships that will never be consummated in any way, except trust, and a sort of emotional dependency.

You said complicit, and that struck a chord because that’s something the book does. Not only playing with the very typical Diaspora storyline—I’m pretty sure the father dying and the boy going back home is what happens in The Namesake—

I mean, I’m not gonna name names, but it’s cliché, and the book is full of cliché, but I hope that, it kind of upends them. The main character is aware that he is a cliché.

And that self-awareness comes through. I remember when you outed Chip and Sherene as being Asian—do you want to talk about that a little bit? I love things that make me feel that sort of shame; because in the book you introduce them and then later on we learn that Chip is Korean and Sherene is Persian, and in both those moments I was like, “Oh, wait a minute, I was definitely thinking that these dudes were white.”

It’s just a little game. It’s a game to play with expectations and racialized characters have to be identified as racialized. I had a clear idea of who these people were from the beginning and then I was like, why do I need to explain it? If they were white I wouldn’t explain it. I hope that you know, the reader’s response to that is to make them question that expectation, that unless specified, a character is read as white.

Talking about those ideas of what is common in Diaspora literature is this heirloom—Ash finds his father’s manuscript; this is what his father has left behind.

Exactly, it’s another cliché.

It also provokes a lot of questions about memory, about what’s left behind, and that ties in really well with a lot of the political stuff. You ask, how much responsibility does Ash have to Kashmir—what was the decision behind that, that you wanted to explode that?

Explode what in particular?

This idea of heirlooms, because it’s an unfinished heirloom. That caught my mind particularly—when someone comes from another country, you have to decide what to leave behind, and Ash’s father is this man of intellect and he decides to write the Great Indian Novel. And then Ash, viewing himself kind of as a failure, kind of not, sort of steps into his father’s shoes by retyping this novel and seeing what he can discover. And using that novel to engage with his dead father.

It doesn’t go anywhere though, right? It’s a process that I think we see in fiction as being kind of rewarding, as a path to the self, I just feel like it’s a little bit disingenuous. Does life really work that way? I don’t know, it’s a question. I don’t know. But at least, in this book, the manuscript never goes anywhere, and then that sort of gets transmuted into the reality of the book, eventually. But Ash’s process of working on it doesn’t go anywhere either.

The riskiest thing to me about this book is that you withheld the epiphany.

Yeah, well, kind of.

You withhold the epiphany with a capital e.

I struggle with that tendency, among, let’s say, North American writers, to sort of take that cultural heritage and cultural inherited trauma and use it for self- discovery. It’s so weird. “I don’t know who I am, I’m going to dig up all this stuff about X genocide that happened to my ancestors to get a better sense of myself.”

The level of solipsism in that is insane! So it’s something the character is aware of, and it’s something that I was thinking of when writing this book. I could spend a year in Kashmir talking to people and living there, but I think that the instinct to then use that to better understand myself is crazy. Like, I grew up in London, Ontario, you know what I mean? So it’s like—the resistance, the way the book sort of sets that up, is a kind of garden path, like he’s going to use this to sort of discover something about his dad and then discover something about himself, but is very conscientiously a dead end, I guess.

I don’t know if there are epiphanies that are withheld. The coda that’s at the end of the book is supposed to lead the reader to a realization that the character’s had, you know, this theme of time and memory that’s sort of been threaded throughout the whole book, that there’s something still within that, there’s something that’s still worthwhile. And that the act of storytelling and, you know, fiction, and the process of engaging with these questions is, in itself, even though they don’t go anywhere, is worthwhile.

I don’t think it’s an entirely cynical and nihilistic book. I feel like though it’s resisting a lot of these things, it’s resisting a lot of tropes and things that I think are themselves cynical. I think that, you know, approaching storytelling as a kind of teleology that will lead you to an end point of understanding is this thing that we’ve developed as a way to talk about fiction, to me, it’s like, is that what life is like?