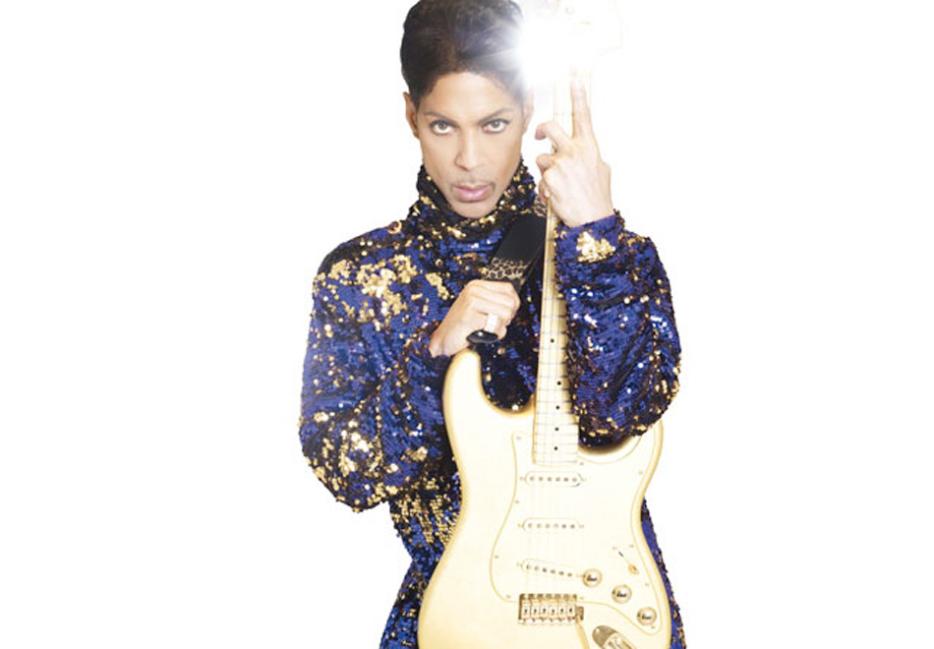

Several city blocks of waiting Torontonians were left to trudge home despondently yesterday afternoon after the rumoured Prince show at Massey Hall dissipated into nothing. (“He just wasn’t feeling it,” a local DJ paraphrased, at least before deleting her tweet.) As I write this, the other famous musician from Minnesota may or may not be planning to make amends tonight, but I was struck by how characteristic the non-event was. Prince is both prolific and reticent. He almost never gives interviews. He records hundreds of songs and then declines to release them. Even that frequently derided name change can be seen as an act of self-negation.

Plenty of musicians shun the media; Michael Jackson gave the tendency its own grotesque performance, fleeing like some tragic Lon Chaney monster. But Prince makes diffidence look like an aesthetic choice, a gesture towards the unknowable. Although it would be facile to describe the whole discography in such terms, many of his greatest songs hinge on minimalism: The strange absence of a bass line in “When Doves Cry,” or the way “Kiss” reduces itself to a single sublime riff. Moments of aloofness or abdication recur throughout his career.

1981: Before the start of his Controversy Tour, on the cusp of “Little Red Corvette” and mainstream crossover, Prince booked a pair of shows at the Los Angeles Coliseum opening for the Rolling Stones. At this point he was wearing bikini briefs onstage and singing about sharing clothes with his girlfriend, so after 15 or so minutes of bigoted, trash-hurling abuse from the Stones crowd, he rightly ran off and flew home to Minneapolis. A conversation with Mick Jagger did get Prince and his band to return for the second date, braving similar reactions. To demonstrate how pitiably deluded that crowd was, here is a typical Prince set from around the same period, still extant on YouTube for some reason:

1985: In the words of the British music critic Tom Ewing: “The rushed composition of ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas’ gave it an awkward, compelling weirdness—but Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie play things a lot safer. They had to: the Band Aid line up was a generation of new stars self-consciously coming of age together, but Quincy Jones’s and Harry Belafonte’s contact books were fat enough to include the really big beasts, ones who no longer appreciated being herded. ‘We Are the World’ is carefully scripted to give each superstar a chance to sing without being hustled out by the next one—or that’s the positive spin on a record which is seven minutes long and almost all chorus.” One should probably note that the genesis of “Do They Know It’s Christmas” was fueled by something more chemical than impassioned empathy, but despite all that, one American star snubbed USA for Africa.

Prince’s motives for skipping the “We Are the World” recording session have never been definitively established, enabling half a dozen entertaining theories: He couldn’t stand to relinquish that much control over the process? There was a bodyguard he had to bail out of jail? Bob Geldof called him a “creep”? He did contribute an exclusive track to the accompanying album, though, and given that a Prince cameo would also be one of several unrealized duets on MJ’sBad, I lean towards the first explanation—but maybe he just preferred to write a cheque for famine relief rather than bellow six words of a lumbering quasi-hymn next to Steve Perry. Poignant piece of music trivia: John Denver asked to sing on “We Are the World” but got turned down for credibility reasons.

1987: Conceived as a back-to-basics funk record after the discursive languor of Sign o’ the Times—it was going to be released with no visible title, artist credits, or cover photography—the Black Album got canceled shortly before its original release date after Prince had an eventful ecstasy trip and decided it was an evil influence. The few promo copies that escaped the dauphin were routinely bootlegged. Prince did give the Black Album a legal release in 1994 before deleting it from his catalogue months later, one more mysterious undertaking.

1998: Despite his caricature as an Internet-fearing crank, Prince’s relationship with technology is more complicated than that: It’s an object of fascination continually disappointing him. (He was an early adopter, as per the two different songs on 1995’s Emancipation called “Emale” and “My Computer.”) The ill-fated Crystal Ball box set was a precursor to every botched Kickstarter campaign. Prince declared that the three discs of unreleased rarities would only be shipped out after a certain number of pre-orders; he only managed to fulfill that promise after massive delays. The purportedly lavish packaging turned out to be more “blank CD case” than “extradimensional sanctum.” And just to emphasize that we were all still stuck in the Clinton administration rather than hanging out with sexy genderless aliens, you had to print the liner notes and cut them out yourself, probably using those colorful safety scissors like a maladroit child. Then Prince released Crystal Ball to retail stores anyway. Maybe he actually does understand the Internet?

2010: Having charged fans $77 for an online subscription service that includes the three new LotusFlow3r albums plus archival videos, unheard tracks and other enticing material, Prince shuts the experiment down a year later after not delivering very much of the latter. This is sort of a pattern with him, right down to the numerology. Some time earlier, he briefly teased New Funk Sampling Series, a seven-disc set of 700-plus Prince samples for $700 (licensing included). It’s the mise-en-abyme of abandoned Prince projects: He decided not to release work he had already released. At least the rumoured ticket price at Massey Hall was only $10.