Sally Horner walked into the Woolworth's on Broadway and Federal to steal a five-cent notebook. She had to, if the girls' club she desperately wanted to join were to accept her into its ranks. She'd never stolen anything in her life; usually she went to that particular five-and-dime for school supplies and her favorite candy. But with days to go before the end of fifth grade, Sally was looking for a ticket to the ruling class, far removed from the babies below her at Northeast School in Camden, New Jersey.

It would be easy, the girls told her. Nobody would suspect a girl like Sally as a thief. Despite her mounting dread at breaking the law, she believed them. On the afternoon of June 13, 1948, she had no idea a simple act of shoplifting would destroy her life.

Once inside, she reached for the first notebook she could find on the gleaming white nickel counter. She stuffed it into her bag and sprinted away, careful to look straight ahead to the exit door. Then, right before the getaway, came a hard tug on her arm.

Sally looked up. A slender, hawk-faced man loomed above her, iron-gray hair peeking out from underneath a wide-brimmed fedora. His eyes, set directly upon Sally's, blazed a mix of steel blue and gray. A scar sliced across his cheek by the right side of his nose, while his shirt collar shrouded another mark on his throat. The hand gripping Sally's arm bore the traces of an even older, half-moon stamp forged by fire. Any adult would have sized him up as well past 50, but he looked positively ancient to Sally, who had turned 11 just two months before. Sally's initial nerves dissipated, replaced by the terror of being caught.

“I am an FBI agent,” the man said to Sally. “And you are under arrest.”

Sally did what many young girls would have done in a similar situation: She cried. She cowered. She felt immediately ashamed.

As the tears fell, the man froze her in place with his low voice. He pointed across the way to City Hall, the tallest building in Camden, and said that girls like her would be dealt with there. If it went the way they normally handled thieving youths, he told her, Sally would be bound for the reformatory.

Sally didn't know that much about reform school, but what she knew was not good. She kept crying.

But his manner brightened. It was a lucky break he caught her and not some other FBI agent, the man said. If she agreed to report to him from time to time, he would let her go. Spare her the worst. Show some mercy.

Sally felt her own mood lift, too. He was going to let her go. She wouldn't have to call her mother from jail—her poor, overworked mother, Ella, still grappling with the suicide of her alcoholic husband, Sally's father, five years earlier; still tethered to her seamstress job, still unsure how she felt about her older daughter Susan's pregnancy, which would make Ella a grandmother for the first time. Sally looked forward to becoming an aunt, whatever being an aunt meant. But she couldn't think about that. The man was going to let her go.

On her way home from school the next day, though, the man sought her out again. Without warning, the rules had changed: Sally had to go with him to Atlantic City—the government insisted. She’d have to convince her mother he was the father of two school friends, inviting her to a seashore vacation. He would take care of the rest with a phone call and a convincing appearance at the Camden bus depot.

His name was Frank La Salle, and he was no FBI agent—rather, he was the sort G-men wanted to drive off the streets, though Sally didn't learn that until it was far too late. It took 21 months to break free of him, after a cross-country journey from Camden, New Jersey, to San Jose, California. That five-cent notebook didn't just alter Sally Horner's own life, though: it reverberated throughout the culture, and in the process, irrevocably changed the course of 20th-century literature.

*

Vladimir Nabokov's 1956 essay “On a Book Entitled Lolita” was an essay he never intended to write. He disdained literal mapping of nonfiction to fiction, as well as the search for moral meaning: “For me a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm.”

Vladimir Nabokov's 1956 essay “On a Book Entitled Lolita” was an essay he never intended to write. He disdained literal mapping of nonfiction to fiction, as well as the search for moral meaning: “For me a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm.”

The essay exists because, by then, Nabokov felt he had to explain himself—that he was a novelist, not a purveyor of smut. Lolita was so notorious that four American publishers refused to publish the manuscript, one saying flatly to Nabokov that, “if he printed Lolita, he and I would go to jail.” The book had a readership thanks to the French publisher Olympia Press, which printed its first, error-filled edition in 1955. Olympia was known as much for publishing workmanlike pornography as it was for mass market, not-exactly-legal editions of James Joyce's Ulysses, J.P. Donleavy's The Ginger Man, and Henry Miller's novels. Nabokov's experience with Olympia was an unhappy one, largely because of the many mistakes introduced into the text, and he would not find proper peace until Lolita was finally (and at significant cost) cleared for US publication in 1958 by Putnam.

Nabokov said he conjured up the germ of the novel—a cultured European gentleman's pedophilic passion for a 12-year-old girl resulting in a madcap, satiric cross-country excursion—“late in 1939 or early in 1940, in Paris, at a time when I was laid up with a severe attack of intercostal neuralgia.” At that point it was a short story set in Europe, written in his first language, Russian. Not pleased with the story, however, he destroyed it. By 1949, Nabokov had emigrated to America, the neuralgia raged anew, and the story shifted shape and nagged at him further, now as a longer tale, written in English, the cross-country excursion transplanted to America.

Lolita is a nested series of tricks. Humbert Humbert, the confessing pervert, tries so hard to obfuscate his monstrosities that he seems unaware when he truly gives himself away, despite alleging the treatise is a full accounting of his crimes. Nabokov, however, gives the reader a number of clues to the literary disconnect, the most important being the parenthetical. It works brilliantly early on in Lolita, when Humbert describes the death of his mother—“My very photogenic mother died in a freak accident (picnic, lightning) when I was three”—or when he sights Dolores Haze in the company of her own mother, Charlotte, for the first time: “And, as if I were the fairy-tale nurse of some little princess (lost, kidnaped, discovered in gypsy rags through which her nakedness smiled at the king and his hounds), I recognized the tiny dark-brown mole on her side.” The unbracketed narrative is what Humbert wants us to see; the asides reveal what is really inside his mind.

Late in Lolita, one of these digressions gives away the critical inspiration. Humbert, once more in Lolita's hometown after five years away, sees Mrs. Chatfield, the “stout, short woman in pearl-gray,” in his hotel lobby, eager to pounce upon him with a “fake smile, all aglow with evil curiosity.” But before she can, the parenthetical appears like a pop-up thought balloon for the bewildered Humbert: “Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle [sic], a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?”

Sally and La Salle—he used the alias “Frank Warner” at that time—moved into a rooming house at 203 Pacific Street in Atlantic City. She called her mother on several occasions, always from a pay station, to say she was having a swell time. For six weeks, Ella Horner thought nothing was amiss—she believed her daughter was on summer vacation with friends.

After the first week, Sally said she'd be staying longer to see the Ice Follies. After two weeks, the excuses grew more vague. After three weeks, the phone calls stopped. Ella's letters could no longer be delivered. Sally's last missive was the most disturbing: she and “Warner” were leaving for Baltimore. Something woke up inside Ella's mind: she'd been duped, her daughter snatched away not with violence, but with sweet-talking stealth. Ella received Sally's final letter on July 31, 1948. She called the police later that day.

Cops in Atlantic City descended upon the Pacific Street lodging house, where they learned the man called Warner had posed as Sally's father. They’d found enough evidence to arrest him, but it was too late: he and Sally had disappeared. Two suitcases full of clothes remained in their room, as did several unsent postcards from Sally to her mother and friends. There was also a photograph, never before seen by Ella or the police, of a honey-haired Sally, in a cream-colored dress, white socks and black patent shoes, sitting on a swing. Her smile was tentative, her eyes fathoms deep with sadness. She was still just 11 years old.

It was terrible enough that the police couldn't bring Sally home. Far worse was the news they had to break to Ella: the man called Warner was really Frank La Salle, and only six months before he abducted Sally, he'd finished up a prison stint for the statutory rape of several pubescent girls.

*

It took 50 years for someone to connect the dots between Sally Horner and Dolores Haze. Packed as Lolita is with countless other allusions, leitmotifs, and nested meanings, excavating a real-life case wasn't top priority for Nabokov scholars. Sally's plight was written up extensively in local newspapers at the time, but the New York Times never bothered, and eventually, even the hometown media forgot about the case.

Nabokov biographer Brian Boyd mentioned Sally's abduction in passing in 1990’s Nabokov: The American Years as part of a list of several other crime stories Nabokov clipped from the papers (Sally appears on page 211, as indexed). Alexander Dolinin, a professor of Slavic Languages and Literature at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, investigated further for an essay published by the Times Literary Supplement in 2005: Not only did he find that Sally's story “reads as a rough outline for the second part of Lolita,” but “the very consonance of the names of the kidnapped girl and her abductor—Sally and La Salle—sounded as if they had been invented by a bilingual punster playing upon the French adjective sale (dirty or sordid).”

Both Sally and Dolly—there, too, concordance—are brunette daughters of widowed mothers, fated to be captive to much older predators for nearly two years. They are similarly threatened, too, with Humbert telling Dolores she “will be given a choice of varying dwelling places, all more or less the same, the correctional school, the reformatory, the juvenile detention home…” Nabokov transplants the big trip to start a year earlier, in 1947, and end, more or less, in 1949.

Dolinin further asserted that a handwritten note accompanying a crucial newspaper clipping in Nabokov's files indicates how much the author knew of Sally's abduction. Nabokov crossed out the phrases “a middle-aged morals offender” and “a cross-country slave” from the article, and scribbled above the text: “In Enchanted Hunters revisited...in the newspaper?” Apparently Nabokov thought to have Humbert find reference to the Sally Horner case in the “book of doom” he encounters at the motel where he consummates his relationship with Dolores Haze, but rejected the idea, opting to be more subtle about interspersing bits of Sally's story throughout Lolita.

Additional resonances show up with deeper reading. The car accident that kills Charlotte Haze after she confronts Humbert about his diary is all the more horrific for the real-life accidents it emulates and foreshadows (more on those later). Yet the parallels between Lolita and Sally were almost as strong as the ones between Dolores Haze and another similarly named young woman instrumental in Frank La Salle's life.

*

Unlike Humbert Humbert, there was nothing erudite or literary about Frank La Salle. When he was employed, which was irregular, he worked as a mechanic. His prison writings lacked the silky sheen of unreliability that is Lolita's narrative hallmark; grammatical mistakes peppered La Salle's rambling and incoherent oral and typewritten declamations. We know little of La Salle's first 40 years, save that he was born in Chicago and eventually made his way to Philadelphia and neighboring South Jersey towns, operating under at least five different pseudonyms. But like Humbert, La Salle preferred his ladies young and almost never legal. That included his onetime wife Dorothy Dare.

Unlike Humbert Humbert, there was nothing erudite or literary about Frank La Salle. When he was employed, which was irregular, he worked as a mechanic. His prison writings lacked the silky sheen of unreliability that is Lolita's narrative hallmark; grammatical mistakes peppered La Salle's rambling and incoherent oral and typewritten declamations. We know little of La Salle's first 40 years, save that he was born in Chicago and eventually made his way to Philadelphia and neighboring South Jersey towns, operating under at least five different pseudonyms. But like Humbert, La Salle preferred his ladies young and almost never legal. That included his onetime wife Dorothy Dare.

When La Salle met Dorothy, she was not quite 18, a brand-new high school graduate, brown curly hair framing an openhearted face (a description that fits Sally Horner as well as Dolores Haze). Fights with her father over his strict parenting style grew so testy she looked for any chance to escape. Apparently, she found it by running off with La Salle.

Dorothy's father was, to understate, displeased with the situation. She was a minor, and Frank, even after shaving off five years from his actual date of birth, was still more than twice her age. Dare got local police to swear out an eight-state teletype warrant for La Salle's arrest on July 22, 1937, and 10 days later, the jig was apparently up. Cops arrested La Salle, going by the alias of Frank Fogg, in Roxborough, Pennsylvania, where he was working, and picked up Dorothy in the nearby town of Wissahickon, where the two had rented a room. Police took the two of them into custody, where Frank dropped a surprise on the arresting officers: the couple had legally married in Elkton, Maryland, and they had the certificate to prove it. The charges couldn't stick.

For a few years, the marriage was a happy one. Frank—living openly under his real name again—and Dorothy moved to Atlantic City. They were still there when the census-takers came knocking in 1940, and noted an addition to the family: a one-year-old daughter named Madeline (not her real name). The marriage began to curdle later that year when Frank was arrested on bigamy charges, few details of which remain other than that he was acquitted. Two years later, when Madeline was three, Dorothy sued Frank for desertion and nonpayment of child support. Family lore had it that Dorothy discovered her husband in a car with another woman, and grew so enraged she hit her over the head with her shoe. It’s also possible Dorothy discovered an even darker truth.

On September 4, 1942, Frank La Salle was indicted in Camden County Criminal Court for the statutory rape of five girls between the ages of 12 and 14. He wasn't arrested until February 2, 1943, though, and pleaded not guilty to the charges in court the following week. A little over a month later, on March 22, La Salle changed his plea to “non vult,” or no contest, and received a sentence of two and a half to five years in Trenton State Prison. Fourteen months later, on June 18, 1944, La Salle was paroled.

He didn't make it on the outside very long. La Salle got his social security card within two weeks as a free man. He worked car mechanic jobs in Philadelphia, but an indecent assault charge landed him in more trouble just a few months later, in October 1944 (Camden County prosecutors dropped the matter on Halloween). The next time La Salle got indicted, in September 1945 for “obtaining money under false pretenses”—he forged a check for $110 at the Third National Bank in Camden—his luck turned, and he headed back to Trenton State Prison on March 18, 1946. Not only was La Salle set to serve 18 months to five years on the new charges, but the clock began on the remainder of the statutory rape sentence for which he’d received parole immediately thereafter. La Salle finished up those sentences in January 1948, and he was paroled again on the 15th of that month.

Dorothy and Madeline's whereabouts didn't interest the news, and they faded from public view.

*

Captivity narratives, such as the recent “found alive” stories of young women including Elizabeth Smart, Jaycee Dugard, and the trio Ariel Castro held in Cleveland, never fail to fascinate. They allow us to understand how kidnappers subjected these girls and women to years of sexual, physical, and psychological abuse. No matter that some, like Smart and Dugard or Colleen Stan, the “Girl in the Box” under her tormentors' sway for seven years, left their abductors' homes, shopped at supermarkets, and even traveled (Stan visited her parents during her captivity period). They survived by adjusting their mental maps so that brutality could be endured, but never normal.

If Sally told the truth, who would believe her story? Who would comprehend she had been abducted when, to all appearances, it seemed Frank La Salle was her father, and a loving one at that?

Day after day of their confinement, their kidnappers told these women their families had abandoned and forgotten all about them. Year after year, their only knowledge of love came from those who abused, raped, and tortured them. Such cognitive dissonances attach themselves, vise-like. Dugard's 18-year manipulation, compounded by bearing two children fathered by her abductor, caused her to deny her real identity to the police at first, only revealing the truth when she felt secure of permanent separation from her kidnappers. Smart, too, needed the same slow-burning trust to tell law enforcement who she really was.

Smart, Dugard, and the Cleveland three published or will publish books about their long-running ordeals. They can tell their stories the way they wish and when they choose, and attempt to make something meaningful of their lives. Sally Horner did not have that choice. While we don't have many details of her day-to-day time with Frank La Salle, what we know speaks to the missed signs, the frustration that no one stepped in, and Sally's own internal strength, damped down until the opportunity to escape finally presented itself.

Dolores Haze, of course, did not tell her own story in Lolita. Instead we have the word of Humbert Humbert, whose charm and erudition allows the reader to forget—briefly for some, completely for others—that he is a monster. The genius of Nabokov is in how his narrative allows for all manner of interpretations of Humbert's motivations, leaving us to confront uncomfortable ambiguity in a way we wouldn't dare with manipulators such as Ariel Castro, Philip Garrido, or Frank La Salle.

*

Having cleared out of Atlantic City, knowing the police were in pursuit, La Salle and Sally settled in Baltimore by September 1948. They kept up the father-daughter pose in the Barclay neighborhood on the east side of the city—at the time a middle-class enclave—until April 1949. She attended Saint Ann's Catholic School at 2200 Greenmount Drive, likely within walking distance of her new home. The Church of Saint Ann's is still open; the school closed in the mid-1970s (a different school, Mother Seton Academy, reopened in the same building in 2009). If records remain of the Saint Ann's years, they’re difficult to come by: the Church had none, and neither did its parish.

They left Baltimore and headed southwest to Dallas, the timing of the move appearing to coincide with Camden County indicting La Salle a second time. Back in 1948, prosecutor Mitchell Cohen indicted La Salle for Sally's abduction, which carried a maximum sentence of three to five years in prison. This second, more serious indictment, for kidnapping, handed down on March 17, 1949, carried a sentence of 30 to 35 years. If La Salle did get word of the new indictment—he told Sally they needed to leave Baltimore because the “FBI asked him to investigate something”—he didn't want to be in striking distance of Camden, where police could find them.

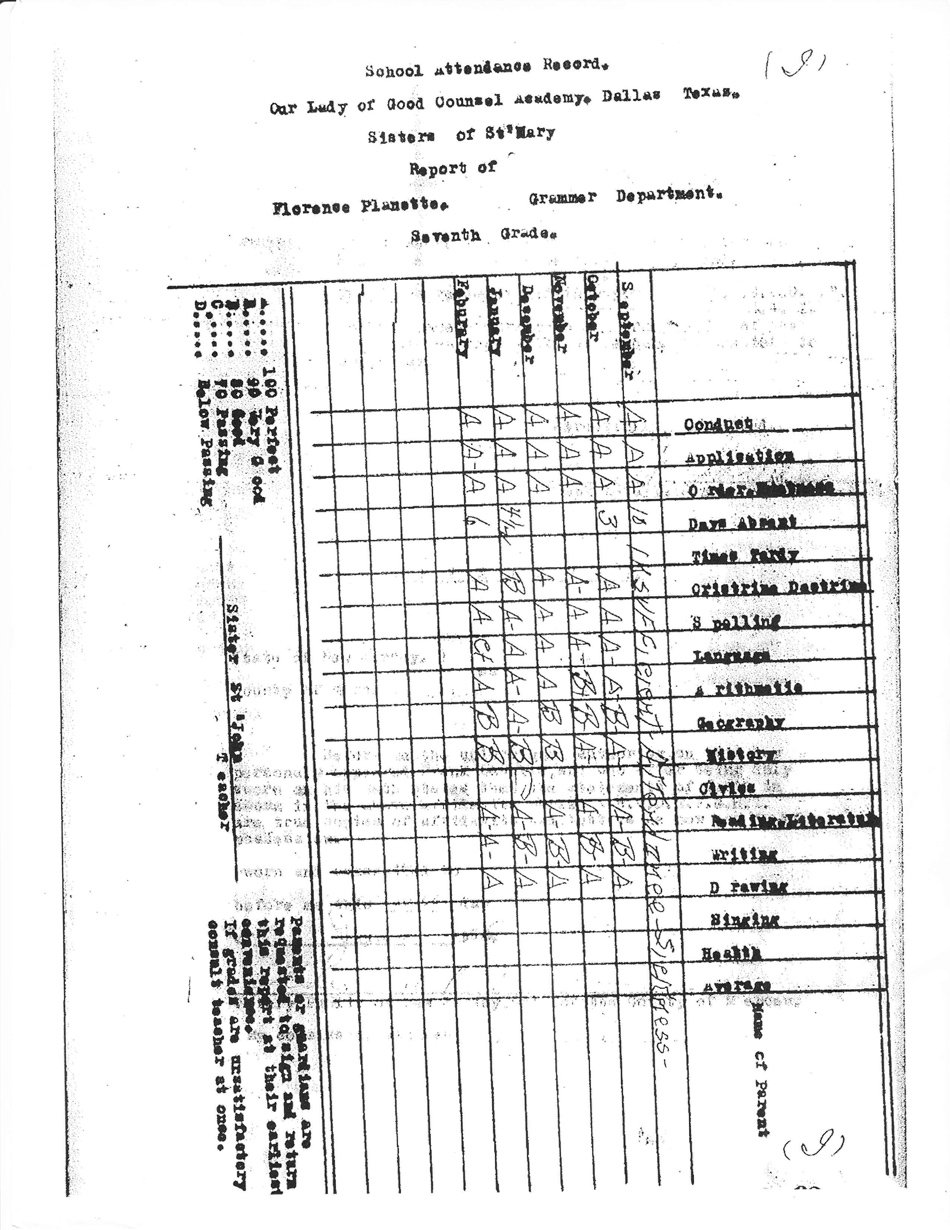

Using the last name of LaPlante, they lived on Commerce Street, a quiet, well-kept trailer park in a more run-down part of Dallas, from April 1949 until March 1950. Their neighbors regarded Sally as a typical 12-year-old living with her widowed father, albeit one never let out of his sight except to go to school. But she seemed to enjoy taking care of her home. She would bake every once in a while. She had a dog. La Salle provided her with a generous allowance for clothes and sweets. She would go shopping, swimming, and to her neighbors' trailers for dinner. And while La Salle, as LaPlante, set up shop again as a mechanic, Sally attended Catholic school once more, at Our Lady of Good Counsel. (It, too, no longer exists, absorbed into Bishop Dunne Catholic School by 1961. The trailer park will be replaced this year by a posh apartment complex.)

A copy of Sally's report card from her time at Our Lady of Good Counsel between September 1949 and February 1950 indicates she was a good student, with her only C+ grade coming in Languages in her final month there. Otherwise, she got primarily A’s and A-minuses, with the occasional B, the latter mostly coming towards the end of the school year. Her worst subjects were Geography and Writing. She also missed 10 days of school in September because she was hospitalized for appendicitis, spending at least three nights at the Texas Crippled Children's Hospital (now the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children).

Sally's apparently happy demeanor in Dallas grew more pensive after the operation. Josephine Kagamaster, the wife of La Salle's business partner in the shop, remarked Sally did not move like “a healthy, light-hearted youngster,” and heard La Salle say the girl “walks like an old woman.” Otherwise, the consensus about Sally and her “father” was that they “both seemed happy and entirely devoted to each other.” Nelrose Pfeil, a neighbor, said, “Sally got everything she ever wanted. I always said I didn't know who was more spoiled, Sally or her dog.” Maude Smilie, living at a nearby trailer on Commerce Street, seemed bewildered at the idea of Sally being a virtual prisoner: “[Sally] spent one day at the beauty parlor with me. I gave her a permanent and she never mentioned a thing. She should have known she could have confided in me.”

Sally might have stayed late at a neighbor's watching television, or even in hospital for several nights, but if she told the truth, who would believe her story? Who would comprehend she had been abducted when, to all appearances, it seemed Frank La Salle was her father, and a loving one at that?

It turned out one woman did believe Sally. And her belief emboldened Sally's nerve to escape.

*

“So my nymphet is not in the house at all! Gone! What I thought was a prismatic weave turns out to be but an old grey cobweb, the house is empty, is dead.” – Lolita, pp. 49-50

Ruth Janish11Sometimes spelled “Janisch” in news reports. was married to an itinerant farm worker. Little else is known about the couple. They moved where there was work and didn't stick around long where there was none. During a fallow period at the beginning of 1950, the Janishes lived in the West Dallas trailer park at the same time as Sally Horner and Frank La Salle. Soon after she met them, Ruth began to suspect that Frank was not, in fact, Sally's father. “He never let Sally out of his sight, except when she was at school,” Mrs. Janish recounted. “She never had any friends her own age. She never went any place, just stayed with La Salle in the trailer.” La Salle, to Ruth, seemed “abnormally possessive” of Sally.

Ruth tried to cajole Sally, still recovering from her appendectomy, to tell her the “true story” of her relationship with La Salle in Dallas. Sally wouldn't open up. The Janishes left for California in early March 1950, thinking they’d have better luck finding work there, but on arrival, Ruth hatched the beginning of a plan. First, she wrote La Salle, urging him and Sally to follow them to the San Jose trailer park, where they could be neighbors again. The Janishes had even reserved a spot in the park for them.

La Salle was in. He and Sally drove from Dallas to San Jose, the house-trailer attached to his car, and arrived in the park by Saturday, March 18, 1950. For some reason, it made more sense for La Salle to take the bus into the city to look for work than to drive. He'd left Sally by herself countless times before, and was confident she would stay put. But this wasn't Dallas, or Baltimore, or even Atlantic City. This was San Jose, on the opposite coast—the farthest Sally Horner had ever been away from home. And change had been brewing inside her, too.

Before leaving Dallas, Sally mustered up the courage to tell a friend at school of her ordeal at La Salle's hands. The friend told Sally her behavior was “wrong” and that “she ought to stop,” as Sally later explained. As her friend's admonishment sank in, Sally began refusing La Salle's further advances. And on the morning of March 21, 1950, Ruth Janish's determined concern and Sally's burgeoning need for change collided in a San Jose trailer park.

With Frank La Salle safely away for several hours, Ruth invited Sally over to her trailer. Knowing this was her only chance, Janish gently coaxed more honesty out of the young girl. She wanted to go home. She wanted to talk to her mother and older sister. Janish then showed Sally how to operate the telephone in her trailer so the girl could make long-distance phone calls.

*

Phones are a recurring motif in Lolita. The incessant ringing of the “machine telephonica and its sudden god” interrupts the narrative, showing Humbert's psyche beginning to fissure as the monster underneath wages war with the amiable surface personality he presents to the world, allowing for Dolores to find some means of freedom. Humbert's paranoia grows as he suspects Dolores has confided the truth in Mona, a school friend: “the stealthy thought … that perhaps after all Mona was right, and she, orphan Lo, could expose [Humbert] without getting penalized herself.”

Dolores's first escape, after she yells “unprintable things” and accuses Humbert of murdering her mother and violating her, occurs as the phone rings and she breaks free of his grip on her wrist (mirroring La Salle's of Sally at the five-and-dime). That escape only lasts a few hours, as Humbert finds Dolly “some ten paces away, through the glass of a telephone booth (membranous god still with us).” After that, she asserts authority as to where they should go next, and then, though the reader is not privy to it, makes a final, mysterious call, presumably to Quilty (whom, earlier in Lolita, she jokes is female) to help her escape. Telephones, Humbert concludes, “happened to be, for reasons unfathomable, the points where my destiny was liable to catch.”

*

Sally called her mother first, but the line was disconnected; she later learned Ella had lost her seamstress job and, while unemployed, could not afford to pay for a phone line. Next, she tried her sister Susan, who lived with her husband, Al Panaro, and their baby daughter Diana, in Florence, New Jersey, about 20 miles away from Camden, where the two worked together in a greenhouse. The greenhouse phone rang, and Al picked up. “Al, this is Sally,” she said. He tried to contain his excitement. “Where are you at?” “I'm with a lady friend in California. Send the FBI after me, please!” Sally cried. “Tell mother I'm okay, and don't worry. I want to come home. I've been afraid to call before.” Sally’s brother-in-law assured her he would do that if she would stay where she was.

After Sally hung up the phone, she turned to Ruth. “I thought she was going to collapse,” Mrs. Janish said. “She kept saying over and over, 'What will Frank do when he finds out what I have done?'”

But Al Panaro came through. He notified the FBI's New York office, which in turn notified the sheriff's office of Santa Clara County. Federal agents and sheriff's deputies sped to the motor court where they found Sally, alone. She was relieved to be rescued, but terrified that La Salle would return. “Please get me away from here before he gets back to town,” Sally said. Police took Sally to the county detention home for juveniles, where she underwent a medical examination.

Having rescued Sally, federal and state agents lay in wait for Frank La Salle's returning bus to the trailer park, and arrested him the minute he stepped off. La Salle not only denied kidnapping Sally, but claimed he was her father, that he had “reared her since she was a small girl,” and was married to Sally's mother. Ella Horner, he told them, “has known where I am and where the girl is every day since I've been gone.” He crowed that the authorities “could have found me at any time. I had a business in Dallas. I always registered my cars in my right name.”

The next day, La Salle was charged with violating the Mann Act22Nabokov refers directly to La Salle's Mann Act arrest in Lolita, but changes the age: “Only the other day we read in the newspapers some bunkum about a middle-aged morals offender who pleaded guilty to the violation of the Mann Act and to transporting a nine-year-old girl across state lines for immoral purposes, whatever they are. Dolores darling! You are not nine but almost thirteen, and I would not advise you to consider yourself my cross-country slave...I am your father, and I am speaking English, and I love you.” [150] for transporting a female along state lines with the intent of corrupting her morals. The police required Sally to be in court to hear the charges. She cried and screamed, seeing her abductor for the first time since her rescue. She also denied La Salle was her father: “My real daddy died when I was six and I remember what he looks like. I never saw this man before that day at the dime store.”

*

Ella was overjoyed to learn her daughter was still alive. “Many times it seemed hopeless,” she said. “But I'll be thankful when I see her and know she's all right.” She also firmly denied any connection whatsoever to La Salle: She had only met the man as he led Sally to the bus that day in 1948. Besides, Sally's father was long dead, and surely La Salle's prior prison record spoke for itself.

It certainly did to the authorities, who decided La Salle was best off with the state of New Jersey. They dropped the federal charges, with California governor (and future Supreme Court Chief Justice) Earl Warren signing an extradition agreement. Camden County prosecutor Mitchell Cohen and city detectives Willard Dube and Marshall Thompson flew to San Jose to escort La Salle back East by train, all shackled to one another, as airlines did not allow prisoners to be handcuffed on flights.

Cohen accompanied Sally, clad in a navy blue suit, polka dot blouse, black shoes, a red coat, and a straw Easter bonnet, on a United Airlines plane arriving in Philadelphia just before midnight on March 31, 1950. It was Sally Horner's first-ever flight. She steadied her mounting nerves by talking about how much she looked forward to seeing her family. She only threw up once, when the plane ran into turbulence just outside of Chicago.

Ella waited at the airport with her family in the back seat of assistant prosecutor William Cahill's car. Several other planes landed first, each one lifting Ella's spirits before crushing them anew. “Why doesn't it come,” Ella said, her face pressed against the car window. Her anguish was short-lived: Sally's plane, delayed 33 minutes, finally landed. Sally's own excitement grew when she noticed her brother-in-law in the mounting crowd, but Cohen told Sally to wait for the other passengers to leave first.

Then Sally spotted her mother. “I want to see Mama!”

“All right, Sally,” said Cohen. “Let's go.”

Sally stood at the doorway, peering into the crowd, then slowly descended the ramp. Ella ran in a frantic flash towards her youngest daughter, holding out her arms. Sally raced down the steps, her face lit up with joy and tears. “Mama! Mama!” Sally cried. She and her mother clung to each other for several minutes, both oblivious to the myriad flash bulbs in their faces looking for the perfect photo to run in the papers the following morning. At first, they wept too loudly to speak. Then Sally wailed what had been uppermost on her mind for nearly two years: “I want to go home,” she sobbed. “I just want to go home.”

Safely in prosecutor Cahill's car, she explained to Sally that that couldn’t happen just yet. Instead, they were en route Camden County Children's Center in nearby Pennsauken, New Jersey, which would care for Sally “until the trial is over.” As their car arrived at the center, so did another one holding Sally’s aunt, Al Panaro, and her sister. “Susan!” she cried upon spotting her older sibling.

“I kissed you at the airport but you didn't recognize me!”

Susan was holding her daughter, Diana, who had been born two months after Sally disappeared. Sally reached for the niece she'd never met and hugged her tightly. “Gee, she looks like pictures of me taken when I was a baby!”

Cohen, exhausted from the trip, gently informed the family that Sally needed to get some sleep. Visits from anyone but Ella were kept scarce to ensure Sally stayed in a calm frame of mind before and during the trial. But thanks to an unexpected development, Sally’s stay at the center didn’t last long at all.

La Salle arrived in Camden on Sunday, April 2. The very next day, he pleaded guilty to the abduction and kidnapping charges, waiving his right to a lawyer. “I don't need any counsel,” La Salle said in a barely audible voice. “I am guilty, and I am willing to go in and plead guilty.” Asked when he wished to plead, he said, “The sooner the better, I want to get it off my chest, and I want my time to commence to run, and I want to avoid this girl any further unfavorable publicity.”

Sally, dressed in the same navy blue suit she’d worn at the airport, sat in the rear of the courtroom. She wasn't asked to testify, never said a word, and did not once look at La Salle. Judge Rocco Palese sentenced him to 30 to 35 years at Trenton State Prison, with the shorter sentence for abduction to be served concurrently. Palese minced no words as he sentenced La Salle, calling him a “moral leper” and declaring: “Mothers throughout the country will give a sigh of relief to know that a man of this type is safely in prison.”

The wire services’ coverage of the discovery of Sally, compared to the more sympathetic, comprehensive reports of the Camden Evening Courier and Morning Post, was a curious mix of sympathy and victim-blaming. The papers often described Sally as “plump” or “husky,” despite 110 pounds on a five-foot frame being nowhere close to fat. (“A little pubic floss glistened on its plump hillock,” Humbert remarks in Lolita, referring earlier, too, to Dolores’s “curiously husky voice.”) Not only did the press repeatedly publish her name, a practice now frowned upon, but they wrote that Sally had been “sexually interfered with” at La Salle's hands, and printed when and where she had sex with him. One UPI report had her admit that although sometimes La Salle “was mean and scolded me a little... the rest of the time he treated me like a father.” Societal norms even invaded Ella's state of mind. A few days after her daughter was found, Ella was photographed holding a picture of Sally, post-rescue. The quote: “Whatever Sally has done I can forgive her.”

*

Humbert Humbert, in the final chapter of Lolita, remarks he would have given himself “at least thirty-five years for rape, and dismissed the rest of the charges,” echoing the sentence Frank La Salle received. That long prison stint meant the Horner family never had to think about Sally’s abductor again. The New Jersey court systems, however, weren’t so lucky. La Salle may have pleaded guilty immediately and shrugged off his right to an attorney, but he still thought he could find a way out of prison. Unfortunately for him, La Salle preferred outlandish, transparent stories to the truth of those 21 months. Unlike Humbert Humbert, who tried to attach some grander meaning to his delusions of exemplary parenthood, La Salle's machinations were crude, obvious, and disappointingly bland.

He applied for, and received, a writ of habeas corpus from the Mercer County Court (Trenton State Prison fell under their jurisdiction), and testified at length on September 24, 1951. While the transcript wasn't available to me, a later court filing by Camden County prosecutor Mitchell Cohen revealed the outcome: La Salle perjured himself on the stand, and ended up serving an additional 30 days in the Mercer County Jail.

La Salle's lengthy Camden County appeal document, submitted to the court in waves between 1954 and 1955, revealed the likely reason for his perjury sentence: he refused to acknowledge that Sally was not, and never was, his daughter, repeatedly referring to her as “Natural Daughter Florence Horner La Salle,” having convinced himself, through the selective reading of past legal outcomes, that “a father cannot be convicted of kidnaping [sic] his own child.”

He spun a shambling yarn about living in Camden, but “not with his family” in January 1948 (because he had just been paroled on the 15th of that month for statutory rape); “doing what he thought right by giving money in sufficient sums to his former common-law wife for the care and maintenance of his [daughter]” (he never knew, let alone had any domestic relationship, with Ella Horner); and seeing Sally “on the streets by herself as late as 12 AM midnight,” at which point he would make her go home and give her money.

He justified his kidnapping of Sally (both in writing and, later, to his actual daughter, Madeline) on the grounds that he was saving her from a mother who was “always out with some man or is in bed,” or, putting words in Sally's mouth, that her mother “does not care what becomes of me. She seems to hate me, and never buys any clothing or take care of me and is never at home.” These poorly written fantasies of devoted fatherhood to a daughter he never saw manifested further when La Salle described Philadelphia trips “to see his other daughter by his legal wife who he was at the time separated from, but there was nobody at home.” (Dorothy, of course, had sued La Salle in 1942 for not paying child support.)

La Salle attested, time and again, to having “sworn proof” that Sally was his daughter, but could never deliver the goods. He even reproved the media for publishing Sally's name when she was found in San Jose on the grounds of “a statute against such publicity for a child.” He claimed his quick guilty plea resulted from being afraid of “MOB VIOLENCE” (the caps are La Salle's) and that the prosecutor, Cohen, “told the defendant there was no use of his trying to get an attorney as no attorney could do any good.”

La Salle's appeal documents include purported affidavits that bolster his claims of loving fatherhood. If the documents are real, they present a series of missed opportunities, in keeping with the times when one simply didn't talk about terrible things that happened at home. If the documents are forgeries, they amplify the grimy, sordid truth of Sally's abuse: that La Salle's fantastical need to present himself as a well-adjusted human compelled him to bury his misdeeds so deep that he lied, above all, to himself.

La Salle never saw the outside world again. He died of arteriosclerosis in Trenton State Prison on March 22, 1966, 16 years into his sentence. He was just shy of 70 years old.

*

Lolita has an unhappy ending, though it’s played for irony and comedy. In Humbert Humbert's telling, Dolores escapes him by running away with the much older, much more corpulent playwright Clare Quilty, only to end up meeting, marrying, and becoming pregnant by Dick Schiller, a mechanic (La Salle's occupation), by the age of 17. No longer the beloved nymphet, her skin sallow and her demeanor dampened deep into her third trimester, Lo still holds Humbert in her thrall for what she once was and still represents, and it is for that lost ideal that he returns to Ramsdale, confronts Quilty, and kills him in a bizarre parody of a duel.

Sally's fate was simply tragic.

When I mentioned the word “abduction” to La Salle's daughter, she interrupted me with some force. “That's not the way he described it to me,” she said, proceeding to parrot the version La Salle presented in his appeal—a version the court had soundly rejected as fantasy.

Details grow sparse after Sally’s return to Camden, just before her 13th birthday, and the commencement of La Salle’s prison sentence. Though she stayed briefly with her mother upon leaving the juvenile facility in Pennsauken, Sally spent the summer of 1950 in Florence with her sister Susan and her family. Al Panaro is now 91 years old and lives in a nursing home facility near Florence, New Jersey—the same one where Susan died in 2012, at the age of 86. He and his daughter Diana Chiemingo, a year into retirement after working nearly three decades as a Burlington County educational assistant, shared their memories of Sally in separate summertime conversations.

Sally finished up eighth grade—she was a year behind—at Clara S. Burrough Junior High School on the corner of Haddon and Newton Avenues, graduating with honors. All recalled Sally being “very smart, an A-student,” and that “it seemed like she knew a subject before it was taught.” She eagerly awaited the next step, high school, and looked forward to college and getting a good job. She looked healthy, if older than her years, ate well, and had reached her full height of just above five feet, two inches tall.

Sally loved everything about the outdoors: the sun, swimming, and especially the Jersey Shore, spending a great deal of time there both before and after her abduction. She seemed happy to most people, but there were moments when “she was not all there,” Al said. “She never said she was sad and depressed, but you knew something was wrong.” She never mentioned Frank La Salle again, and the family maintained the same silence throughout their lives. “We're very private people,” Diana said. She didn't learn of her aunt's abduction until her late teens.

Ella found intermittent work as a seamstress, and mother and daughter still lived in the two-story rowhouse on Linden Street. When not in Florence with the Panaros, Sally worked summers as a waitress. She had plenty of friends. One of those girls, 15-year-old Carol Starts, a Burrough classmate, accompanied Sally on a trip to the shore town of Wildwood one weekend in mid-August. It would be Sally's last.

No one knows if Ella had reservations about letting Sally go. But on Saturday, August 16, she gave her 15-year-old daughter permission to take the bus with Carol to Wildwood, where the girls planned to stay at a resort. What happened next, the local papers reported the following Monday: Carol fled the resort by bus on Sunday evening, August 17, arriving in Camden that night, but Sally stayed on—she had met a young man at the resort earlier that day, and he promised to give her a lift back to Camden early the next morning. Ella had no idea who the man was. It was entirely possible he and Sally met for the first time that Sunday.

Sally and the young man, 20-year-old Edward John Baker of Vineland, a sparsely populated South Jersey town, set out as planned in the early morning hours of August 18, 1952. Just after midnight, somewhere along the Woodbine-Dennisville Road (now part of Interstate 78), Baker drove his 1948 Ford sedan into the back of a parked truck on the road, knocking it into another parked truck. Baker emerged from the four-car collision with minor injuries, which he had treated at Burdette Tomlin Hospital at Cape May Courthouse. The crash killed Sally instantly.33Edward Baker did not respond to letters or voice mails, closing down the most direct avenue to information about how he met Sally, how well he knew her, and the car accident that killed her. I subsequently learned he died on July 28, 2014, aged 82, having lived in Vineland his entire life. Baker also may not have wanted to talk because Sally's death paralleled another cruelly ironic family tragedy: On the afternoon of Wednesday, May 17, 2007, Baker's 48-year old son, Edward Baker Jr., fell asleep in his Mercury Grand Marquis, crossed the lane and into the median, and slammed into a tree along the shoulder of Route 55. Baker Jr., too, died instantly.

Her death certificate, issued by Cape May County three days later, listed the cause of death as a fractured skull from a blow to the right side of her head. She’d broken her neck; other mortal injuries included a crushed chest and internal injuries, as well as a right leg fracture above the knee. The coroner didn't bother with an autopsy. Sally's death was swift and clear.

The damage to Sally's face was so severe that the state police felt Ella would be too traumatized to identify her daughter. Instead, Al Panaro went to identify his sister-in-law. “The only way I knew it was Sally was because she had a scar on her leg. I couldn't tell from her face,” he told me. A veil covered her at the funeral in Camden, attended by dozens of people, including a slew of aunts, uncles, cousins, and schoolmates.

Police arrested Baker and held him, while and after being treated for his injuries, on a charge of death by automobile for action by the Cape May County Grand Jury. Two years later, in June 1954, the prosecutor's office dropped the charges. They gave no reason.

*

Frank La Salle made his presence known to the family just once: he sent a spray of flowers to Sally's funeral. The Panaros insisted they not be displayed.

*

Dorothy Dare rebuilt her life while her former husband was in prison or on the run with Sally Horner in a manner that has some kinship with what Dolores Haze had in store for her as Dick Schiller's wife. Dorothy spent the Second World War working at the Navy Yard, taking an apartment in Philadelphia and visiting her daughter, who spent summers in Brooklyn and winters at her grandfather's house near Merchantville, whenever she could. After the war, when her daughter was 10, Dorothy met and married an army veteran several years her senior. He adopted Madeline and they had another child. Their marriage lasted almost four decades until his death in 1986.

When her children were grown, Dorothy got a job with a small advertising firm, and then with Campbell's Soup, whose headquarters were, and still are, in Camden. She worked for Campbell's for 30 years, retiring in 1991. For more than 50 years, Dorothy was active in her local Baptist Church, serving several years on the Board of Deaconesses. When Dorothy died at 92 in 2011, her survivors included her children, as well as almost a dozen grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The longer Dorothy lived, the more distance she put between her turbulent early life with Frank La Salle and the more settled, family-oriented existence she likely always sought.

Madeline did not learn any details of her father's imprisonment until she was in her early twenties, newly married with children. “There was an article in the newspaper, and my mother felt she had to tell me,” she said in a telephone interview in August. “I wanted to see him. I wanted to talk to him.” She re-established relations with La Salle in the final year of his life, visiting him in Trenton State Prison along with her children, pre-schoolers at the time. When he was up for parole, sick with lung and heart problems, Madeline volunteered to have him live at her place should he be released early. That did not happen.

“When I looked at him, I could see a lot of myself in his face,” Madeline, now 75, said. “My husband picked it up right away. We talked as father and daughter would talk. He made model boats and leather pocket books. There wasn't a strain. He was just dad. Truth be told, I never thought about whether he was guilty or not guilty.” Just as John Ray, Jr. became the conduit for Humbert Humbert's so-called confession, so did Madeline, unwittingly, become the keeper of Frank La Salle's version of the story. When I mentioned the word “abduction” to Madeline, she interrupted me with some force. “That's not the way he described it to me,” she said, proceeding to parrot the version La Salle presented in his appeal—a version the court had soundly rejected as fantasy.

*

Lolita has sold more than 50 million copies worldwide in the 60 years since its original, furtive publication. As with all great works of literature, readers return to it, finding meanings in the text they’d missed before. “When I first read Lolita, I thought it was the funniest book I'd read in ages. When I read it again, I thought it was one of the saddest,” said Elizabeth Janeway in her rave for the New York Times Book Review. (The paper's chief daily critic at the time, Orville Prescott, panned it.) The novel could be a morality play, or completely amoral. It could be a cosmic joke played by the most unreliable of narrators, Humbert Humbert. It could be a paean to the romantic novel (a theory Nabokov accepted), or to the English language (even if switching from his “untrammeled, rich, and infinitely docile Russian tongue” was Nabokov's “private tragedy”). It also could be, as Nabokov abided with wry half-approval, an allegory about Europe's debauching by America.

Lolita's many layers also hid the story of Sally Horner. Sally's tragic tale wasn't the initial spark, but the gas at the pump to keep the road trip going when the car was perilously close to breaking down. That apparently throwaway parenthetical, “Had I done to her...?” flashes neon bright with significance and warning. Not only must Humbert Humbert answer that question with a denial-stripping yes, but so too must Vladimir Nabokov. Readers can, if they wish, put aside Dolores Haze as a character in a novel, even a great one. Sally Horner can't be cast aside so easily, her legacy to be remembered as a young girl forever changed by a middle-aged man's crime of opportunity. A girl denied the chance to grow up. A girl immortalized, and forever trapped, in the pages of a classic novel of satire and sadness.

An earlier version of this story identified the Lolita character Clare Quilty as a dentist, rather than a playwright.