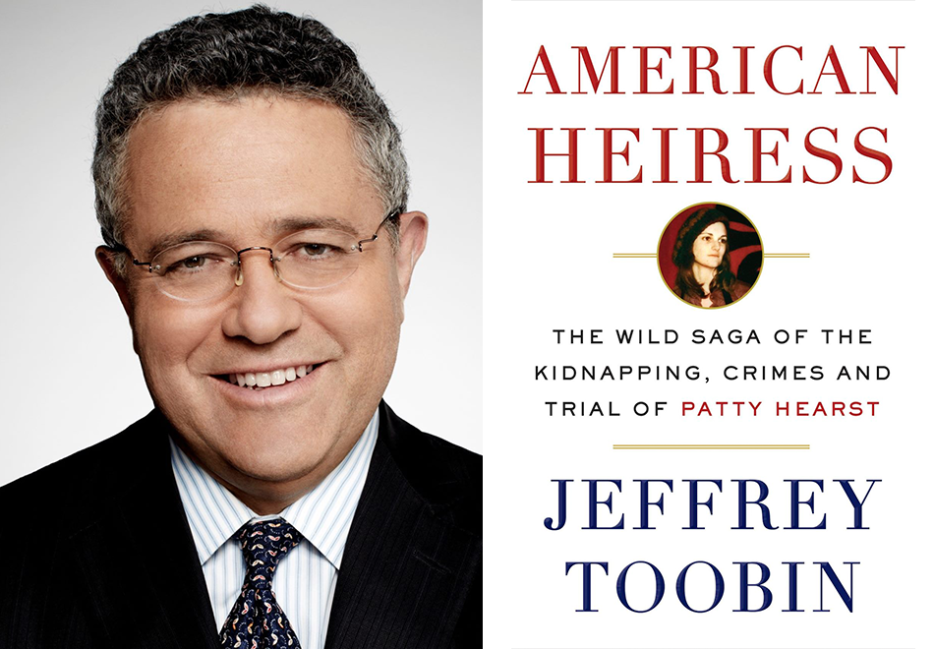

Getting a hold of Jeffrey Toobin was no small task. He is a staff writer for the New Yorker and was briefly in Toronto at the end of August to promote his new book, American Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst, which revisits the notorious 1974 kidnapping of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst's granddaughter by a fringe revolutionary organization. The first call went to voice mail. The second reached Toobin in the customs line at Pearson International Airport, where he was told to hang up the phone. The third, after clearing the line, was the proverbial charm.

In the half-hour or so before his flight back to New York boarded, Toobin talked to me about why the Hearst case fascinates forty years after the fact, the cultural appetite for “trials of the century,” and unexpected case cameos from documentary filmmaker Errol Morris and OJ Simpson trial judge Lance Ito.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Sarah Weinman: I wanted to start with the opening line of Dana Spiotta's New York Times review of your book: “Captivity tales fascinate us because they challenge our fantasy of self-determination.” That, in a nutshell, exactly encapsulates the story of Patricia Hearst. Do you agree and is this idea why you became interested in writing about the case?

Jeffrey Toobin: I think by and large I do agree. The mystery in this story is about Patricia's self-determination. Did she join the Symbionese Liberation Army, or was she coerced? This is the central question of the case. One reason the case has such enduring fascination is because this not a simple question. And it's not easy. What's so compelling is it's not open and shut in terms of how much free will Patricia had in the course of the year and half with the SLA. That's why people are so interested in the case, [it's] complicated and hard.

Sure, that makes sense. But I was curious as to why you in particular were interested in writing about Hearst and why now.

A couple of reasons. I did a story for the New Yorker three years ago about a gang in Baltimore, the Black Guerrilla Family, that had taken over a jail. Their leader was George Jackson. I got interested in the movement, the grief alliance between the counterculture and prisoners. The SLA came out of the same movements.

I was talking to [my US editor at Doubleday] Bill Thomas about that, and he came back with, “well, what about Patty Hearst?” I replied that there must be a million books on the case. But I found to my delight that no journalist had looked into it for decades.

I had covered the prior trial of century. And I was also just fascinated by the 1970s. I was a kid then and not terribly aware of what was going on. It's not much more high-minded than it was.

There were plenty of media reports that Patricia Hearst didn't want to talk to you, almost to the point of disdain. But because there were so many prior sources—interviews, court records, transcripts, her own memoir Every Secret Thing—how necessary would it have been for her to speak with you directly?

I felt it was very important to have her perspective in the book. She wrote her own book. She testified in court. She gave many interviews to the FBI. Her position was well known. I do wish she had spoken to me, but I don't think there was a huge gap.

Could she really add more insight now than she did at the time? What were you hoping for her to say now that she didn't then?

I'm not sure, to tell the truth. I guess I am a greedy journalist. Want more access, rather than less. I have no doubt that I would have found interesting questions to ask her. But it's not like there was one specific question I needed answers to.

I had a question about your research methods, namely about the trove of documents you obtained from SLA member Bill Harris. You devote, understandably, a fair amount of space to this in the acknowledgments section. Was there ambivalence on your part about how you obtained the documents, and how satisfied are you that it's journalistically okay?

I reached out to Bill Harris and found to my surprise that Bill, who is very much a pack rat, had been assembling every doc he could find about the SLA, including court records in every trial involving the SLA. All of the discovery, FBI interviews ... just an enormous amount of material. As he explained it to me, he had a deal to sell it to a university library that had fallen through. So I bought [his archive] instead. When I'm finished with it, which I hope will be soon, once I deal with some logistical challenges, I will donate it all to Harvard Law School, which holds my archive.

So do you see this transaction on par with paying a state or federal agency for court records? I don't want to belabour the point, but...

No, that's a fair question. I'm well aware of ethical prohibitions on not paying for interviews, and I have observed [them] throughout my career. Documents, physical objects, and photos are another matter. Paying for those things is something people do. These documents clearly had a monetary value, and I paid for them. The end result is that I think, once the documents are readily available, I will be contributing to the broader history of the 1970s.

When I read the broader sections about the 1970s in your book I was reminded of Days of Rage by Bryan Burrough, which was a fascinating window into how fraught the American landscape was with nihilism, anarchy, kidnappings, bombings. As much as we are in a weird time now, was it really so much worse in the 1970s?

I was completely flabbergasted and amazed at what a wreck the country was back then. A thousand bombings a year, two hijackings a month, Watergate, the energy crisis, economic decline, the Yom Kippur War, and nowhere was it worse than in the Bay Area. A revealing fact of popular culture: when Warner Brothers needed to find a city to set the Dirty Harry movies [featuring Clint Eastwood] they wanted what was then the most dangerous city in America: San Francisco. I came of age when San Francisco was a glamorous prosperous high tech city, but it was falling apart in the 1970s.

I have to admit I was a bit surprised you hadn't heard of the Zebra Killings. Granted there were other serial killers running about.

Right, like the Zodiac –

Oh I didn't mean the Zodiac. I meant more obscure ones, there's this unsolved case nicknamed The Doodler, for example.

Are you from around the Bay Area?

Oh, no. Crime is my beat, I just pay attention.

Well, going back to the Zebra killings. There is a book about it, but it's not very good. There ought to be another one, it's not for me but it might be for someone. I believe that one or two of the perpetrators are still alive and in prison. One or two have died. Those were some scary guys.

I had also read David Talbot's Season of the Witch, deals with SF in particular. I do quote from it at least once or twice [in American Heiress.] It deals mostly with the 1980s, not the 1970s, but it gives the best picture I know about the craziness of San Francisco.

We can't really talk about the Hearst case without talking about issues of consent. For example, as you discuss in the book, there is an unresolved debate about whether Patricia slept with Willy Wolfe of her own free will or whether it was rape. But how could she consent when every interaction stemmed from her initial, non-consensual kidnapping? How can we say she didn't consent to sex but did consent to violence?

I do think sex and violence are different. It's an ugly truth of human relations that a relationship that began without consent can evolve into one that was consensual. That is what the jury believed happened between Willy Wolfe and Patricia. I think by the same token, a woman who was violently and horribly kidnapped—I know there are some conspiracy theories out there of prior knowledge which I reject completely—can become part of the group after nineteen months.

Look at her behavior. From the first bank robbery, shooting up Mount Sporting Goods, having opportunity after opportunity to leave, the next two bank robberies, the death of Myrna Opsall, the bombs set off in Northern California, her visits with Steve Soliah, the encounters with police, and so on. This was a person who had chosen to stay with the SLA. That is not inconsistent with her kidnapping. People change.

Do you see an arc of authority figures in Patricia's life then?

It's not an arc, but a line! I don't want to get too deep into psychoanalysis of someone I've never met. But I will say a lot of people have types in romantic relationships. For Patricia, going from her school teacher to her kidnapper to her protector to her bodyguard ... you don't have to be Sigmund Freud to figure out she had a type.

How much of a difference is it, if at all, that Hearst was above legal age when everything began? It's a counterfactual, but what if she had been fifteen or sixteen at the time of her kidnapping? Could we then consider her to be a rational actor?

Of course nineteen is different from sixteen. I can't really address a counterfactual. Nineteen is young but it is adult. I think that's relevant. I don't want to claim greater expertise than I have, but clearly children are different than adults.

You arrive at a conclusion about Hearst that, and I'm paraphrasing, she was a malleable opportunist, ready to go along with whomever held authority, and a rational actor throughout. In a way, whether she was with the SLA or back among the rich set, was her whole life about survival? Or putting trust in someone else to tell her what to do? Is that bad? Or just a coping mechanism? What do you make of it as a life strategy?

That's a little more psychoanalytic than I am comfortable being. My approach in describing Patricia was to focus on what she did and what she said, not on the labels applied to her. Obviously I discuss them. It's so easy to get caught up in buzzwords, which are journalistic, not medical.

Right, that's why I didn't bring them up in my question.

And I don't use them except to further discussion of her behavior. The point is, the question you ask requires me to speculate more on her psychological makeup.

By something of a coincidence, or perhaps serendipity, American Heiress was published just months after the airing of The People vs. OJ Simpson, based on your book The Run of His Life. And the JonBenet Ramsey case is about to get another double-airing, as is the Menendez case. Why are we going back to these iconic, highly publicized crimes now after years, even decades? What do we see now that we couldn't see then? What's going on, in your opinion, in the culture? What new things can we learn from this?

I wish I had a great overarching theory for you. I don't. Big stories are always worth revisiting. Interesting stories never get old. We are interested in the stories that we grew up with and wonder what more we need to know. OJ didn't stop being fascinating because twenty years had passed. During that time between the publication of my book and the miniseries, I had been approached many times about a film version. The objection I always heard was, a) people are sick of it b) everybody knows the whole story anyway, even though I knew this wasn't the case. It took Ryan Murphy, who had the moxie and intelligence to champion it at Fox. He's such a valuable figure there.

What's been the response to American Heiress so far, and has there been any difference between those who are familiar with the case versus those who weren't? Does it break down by generational lines?

That's an interesting question. The universal reaction of both sides, those who knew of Patricia and those who didn't, is, “I can't believe something so crazy took place.” The sheer improbability of it. The craziness of it is something that everyone has said. Even as crazy as OJ was, and it was pretty crazy, it didn't have this surreal reversal of Patricia changing sides. There's an enduring mystery about her.

The other thing is people have strong feelings. Most people say nice things, but some say I was too harsh on her, while others say I was too soft. I think the reason the book is doing well is because people are puzzled and fascinated by Patricia's role.

It's similar to when I was an AUSA prosecuting white collar crime. There would often be little dispute on facts. The question is, what was their intent? Did they intend to violate law and commit the crime? Or was it bad luck? Proving intent is hard. The business with the monkey [necklace] was so significant to the jury.11During Patricia's trial, the revelation that she'd kept a necklace given to her by Willy Wolfe was a major turning point. It was a clue to Patricia's intent.

Finally, I wanted to ask about a moment early on in American Heiress. You describe how, before the kidnapping, Patricia was at a dinner with her then-boyfriend Steve Weed and met Errol Morris. He spent the dinner talking about interviewing Ed Gein and Patricia was much more interested in hearing about serial killers than anything Weed had to say. But you didn't cite a source for this anecdote. Did Morris talk to you about this?

Errol told me.

He told you!

He just told me, simple as that. I don't know where first I heard the story...once you put out the word that you are working on a book like this, people will tell you stray facts. I don't remember who told me that Errol was a grad student with Steve Weed, but once I knew, I called up Errol, and he told me what happened.

Here's another strange story. On the night of the kidnapping, there was a neighbor, Steve Tsuanaga, who came in who got tied up on the floor. I wanted to interview him but I've been told he has had a rough time since. I went through his lawyer who said Steve didn't want to talk to me. But in chatting with the lawyer, he said, “Here's a crazy story: Lance Ito lived in the house behind Patty and Steve, and he was there the night of the kidnapping.”

I talked to Ito. He said no, he hadn't witnessed the kidnapping. The anecdote got garbled, and told me the real story, that of seeing [SLA member] Joe Remiro at the firing range with a machine gun. People hear things third-hand and they pass it along to you, and then you have check it out. Either it turns out to be true, false, or garbled in some interesting way.