The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call “out there.” Some seventy miles east of the Colorado border, the countryside, with its hard blue skies and desert-clear air, has an atmosphere that is rather more Far West than Middle West. The local accent is barbed with a prairie twang, a ranch-hand nasalness, and the men, many of them, wear narrow frontier trousers, Stetsons, and high-heeled boots with pointed toes. The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveller reaches them.

-From In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

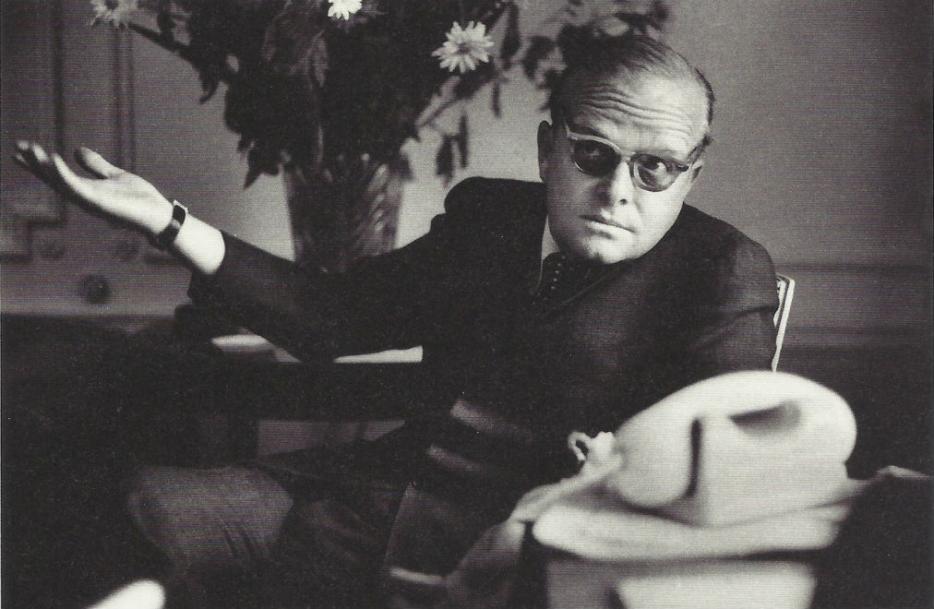

Has there been a more evocative opening of a nonfiction book than this first paragraph of Truman Capote's "nonfiction novel," In Cold Blood? This year is the 50th anniversary of the book's publication in 1966 and it's a reminder that with this book, Capote managed to simultaneously achieve commercial success and earn critical respect. But his modern nonfiction classic is also among the most controversial of all works of journalism.

In Cold Blood is seen as a pioneering book, and was originally published as a series in The New Yorker. It was the first conscious attempt to harness the techniques of fiction and journalism to document a crime, effectively inventing the modern true crime genre. Why a crime? Capote said “murder was a theme not likely to darken and yellow with time.” The book has sold millions of copies and is in print to this day; it has been translated into 30 languages and studied on university curriculums. It was the subject of a black-and-white movie in 1967, a colour remake in 1996, and films about the author’s reporting on the crime came out in 2005 (Capote, with Philip Seymour Hoffman as the titular character) and 2006 (Infamous, with Toby Jones).

At the heart of the text was the key technique that is perhaps the reason the work lends itself so well to cinema: reconstructing scenes and dialogue. Reading In Cold Blood is a singular experience, more engrossing than any of Capote’s fiction, showing a writer in command of his powers. But in the decades since the book was published, evidence of Capote’s elastic attitude toward the truth surfaced. In just one of many examples in Gerald Clarke's 1988 biography of Capote, Clarke detailed how a key moment at the end of the book, when Kansas Bureau of Investigation Detective Alvin Dewey met a girlfriend of Nancy Clutter’s at her gravesite, never happened. In the 2012 book, Truman Capote and the Legacy of In Cold Blood, author Ralph L. Voss' research emphasizes the ways that Capote changed timelines, invented scenes and exaggerated the role played by Detective Dewey, his hero, among many other examples of fact-fudging, many of them departing from Capote's own 6,000 pages of notes.

It didn't help matters that at the time Capote publicly declared his book was entirely factual. Also, he bragged that he didn't use a tape recorder nor take many notes when conducting interviews, relying instead on what he claimed was a near-photographic memory. After Capote's death in 1984, George Plimpton told The New York Times: "Sometimes he said he had ninety-six per cent total recall and sometimes he said he had ninety-four per cent total recall. He could recall everything but he could never remember what percentage recall he had."

In a journal entry in 1967 about the actor Robert Blake, who portrayed Perry Smith in Richard Brook's film adaptation of his book, Capote wrote: "Reflected reality is the essence of reality, the truer truth … all art is composed of selected detail, either imaginary or, as in In Cold Blood, a distillation of reality."

In Cold Blood really should have carried the disclaimer "based on a true story," like so many movies do today. But that wasn't Capote's ambition at the time. After successfully writing fiction, he wanted to create a masterpiece based on the power that comes when the public believes what they're reading is true.

The book raises many questions. How much “fiction,” if any, is permissible in a work of creative nonfiction? Does artistic vision trump verifiable reportage? Can we forgive the sins of writers experimenting with long-form nonfiction at a time when clear guidelines hadn’t been established? Writer and crime specialist (both fiction and non) Sarah Weinman and I will discuss Capote and his legendary book.

David Hayes: So, with all the talk of contemporary writers producing creative nonfiction books but mixing fiction in with it—I’m thinking of James Frey with A Million Little Pieces; Joe McGinniss with his biography of Ted Kennedy; Edmund Morris with his biography of Ronald Reagan—we often forget the classic In Cold Blood. Some believe that we can “grandfather” Capote’s crimes because in the mid-’60s, he and others like him were experimenting with forms and no one had laid out clear guidelines for this kind of long-form nonfiction. Do you think that’s fair or is Capote getting off too lightly?

Sarah Weinman: An excellent question to kick off this discussion, and I think I go back and forth. On the one hand, even as far back as the late 1950s/early 1960s, when Capote (with Harper Lee) went to Holcomb to research the crimes and talk to everyone there, “standard journalistic practice” wasn’t as entrenched as it certainly is now—but was much more so than, say, the 1920s, when newspaperpeople trampled on crime scenes willy-nilly (cf. the Hall-Mills murders). But on the other hand that ending is entirely made up and is not defensible—why was it so important for Capote to end things that way, putting words in the mouth that were never said, by people who may or may not have existed? Still, the ending doesn’t take away from the power and the brilliance of the entire book, but does leave readers—or at least this one—with a slightly unpleasant taste. It seems another example of Capote’s self-absorption, valuing himself above the story. But it worked.

DH: As much as I’ve liked re-reading In Cold Blood (twice when I was writing my first book, which was true-crime), I think Capote was more style than substance. To me, Breakfast at Tiffany’s was the only novel of his that I liked. He wrote another supposedly factual piece after In Cold Blood: Handcarved Coffins, which he called “a nonfiction account of an American crime.” I loved it. It was as absorbing as In Cold Blood, but I noticed a few odd things from the start. Main characters with one pseudonymous name, for legal reasons, Capote claimed. When people started investigating the details of that story it appeared to be entirely fictional. So why didn’t he just write In Cold Blood and call it “fiction?” I think because nonfiction was the hot genre in the ‘60s and into the ‘70s. Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion and the rest of the “New Journalists.” That stuff sold and got a lot of attention. But nonfiction often doesn’t allow you to craft such perfectly symbolic moments (like the ending of In Cold Blood). And calling it a “nonfiction novel,” a new literary genre, guaranteed attention. And Capote was nothing if not a self-promoter.

SW: Handcarved Coffins! I haven’t read all of it, and was dissuaded largely because of the Times (London) piece that thoroughly debunked its veracity (and was itself, as I recall, an entertaining exposé.) This would also be a good time to discuss how In Cold Blood was viewed within The New Yorker itself, since it seems like Capote kind of pulled a fast one on editor William Shawn, promising one kind of story—aftermath, about family—and then delivering a crime story above all, even if it was a crime story outstandingly written and doing things that “true crime” had not really tried to do before. And sure, the magazine printed the multi-part version first and those issues sold insanely well after what seemed like years of advance promotion, but somehow it never really sat well with Shawn. And how much of that came down to snobbery about covering crime, even though the magazine already had an “Annals of Crime” section? It’s interesting to look at this snobbery in light of what is purported to be a revival—Serial/The Jinx/Making a Murderer—but one that is more perennial. Capote knew crime stories sold, lurid stories already had an audience, but he was going to do it his way no matter what.

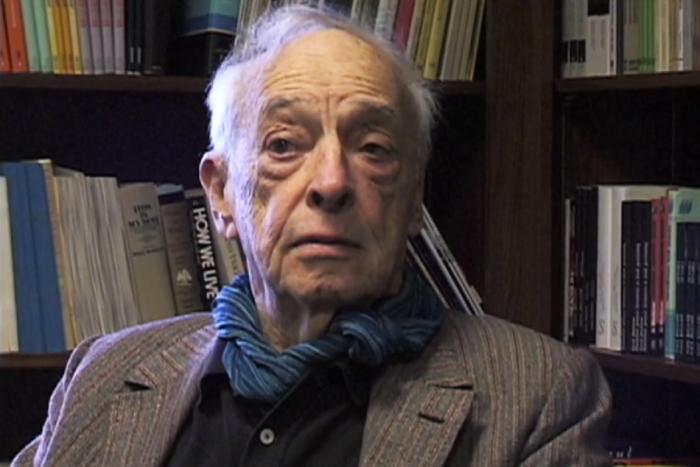

DH: Time magazine and The New Yorker invented “fact-checking” and The New Yorker has always prided itself on its accuracy. Ben Yagoda, who wrote a book about The New Yorker, talked about Capote’s fact-checking materials being in the University of Delaware’s library. The checker was a guy named Sandy Campbell who went with Capote to Kansas at one point. According to Yagoda’s reading of the files, fact-checking at The New Yorker was mainly about verifying dates, spellings of names, distances, physical descriptions of buildings, etc. It seems a lot of stuff was accepted “on author,” as the saying goes. The more respected and valued the writer, the more likely a publication would accept a lot of what he/she wrote. Remember that another respected New Yorker writer, Janet Malcolm, was sued by psychoanalyst Jeffrey Masson over some details in her New Yorker profile of him (which later became a book). Still, it’s surprising that Campbell wouldn’t have talked to some of the many sources who were still alive and appeared as characters in the book. (For example, ask Alvin Dewey and Nancy Clutter’s friend, whom Dewey supposedly met near the gravesite, whether that meeting happened. That’s the invented scene that ends the book.)

SW: Fact-checking is a godsend, having worked with some incredible, thorough, sharp checkers on pieces over the last few years, but yes, it does seem to have been applied differently to those of differing fame. I did want to circle back to the idea of how “ground-breaking” the whole nonfiction novel concept was as it relates to true crime itself, since it does seem, as you pointed out already, to be of a piece with the emerging “New Journalism” genre. Is it that the substance of crime stories was already so suffused with lurid detail that it wasn’t necessary to apply distinctly literary narrative devices in the way Capote did? Without In Cold Blood would we have had Joan Didion writing about the Manson Murders, for example?

DH: As long as there has been crime there have been town criers or writers telling people about it. In the early 18th century, Defoe wrote about a criminal named Jonathan Wild. Some of the most interesting early newspaper work of the 19th and 20th centuries was accounts of crimes or disasters. A crime has built-in drama, notoriety, and an opportunity to reveal aspects of a society at that particular time, so that would make it a natural subject for ambitious writers. In Tom Wolfe’s anthology, The New Journalism, which gave the movement its name, there were several crime stories. (Joan Didion’s “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream”; James Mills’ “The Detective”; an excerpt from Hunter Thompson’s “Hells Angels”.)

SW: That it does. For the piece I wrote for the Guardian about true crime earlier this month it was amazing, if strange, to revisit crime stories written by Benjamin Franklin (!) not to mention Cotton Mather’s pamphlets and proselytizing, which would play out in such awful ways with the Salem Witch Trials. And later in the 20th century with coverage by the likes of Dorothy Kilgallen and Miriam Allen deFord (and my own personal touchstone of excellent journalism written on deadline, Mike Berger’s New York Times story on Howard Unruh’s mass shooting in Camden the morning after it happened, which deservedly won a Pulitzer).

For centuries we’ve been enraptured and revolted, thrilled and petrified, by crime stories and what meaning they might have. So no wonder Truman Capote wanted in on that, so to speak. And it seems, now that we’re venturing near the end of this conversation, an excellent idea to talk about the ways in which In Cold Blood still influences us half a century on. For me it’s largely indirect: the novelistic way of telling a seemingly “just-the-facts” story. A good book to argue with over methodology. How do you see the book and its influence?

DH: Oddly, I think Capote’s reputation rests almost entirely on In Cold Blood. But I’m sure Capote wanted his fiction to be what he would be remembered for. In Ralph Voss’s book, Truman Capote and the Legacy of In Cold Blood, he argues that Capote was always an accomplished stylist but a second-rate writer of fiction. In Cold Blood, though, represented in the ‘60s the possibilities of writing about crime. That reportage could also be artful.

SW: I am inclined to agree, even if that evaluation would fill Capote himself with utter horror. But it does show how culture makes its own judgment independent of an author’s hopes and aspirations. And In Cold Blood more than holds up, despite the flaws, despite the ways in which we can argue with how Capote put it together. Its power is so pervasive it got law enforcement to look at a similar crime in Florida, in a place where Hickock and Smith were apparently in the vicinity (though the connection appears to have been ruled out, or the evidence is too minute to test with proper results.) It overshadows everything Capote did after—and, it could be argued, everything Harper Lee did, too, since she tried her hand at a true crime story and did not finish it.

As the crime popularity continues, and as people find different ways to tell those stories, it’s difficult not to think of In Cold Blood as the worthy elephant in the room. You can’t ignore it or discount it, and why should you? Fifty years on it has that dark, compelling power still.