The first time I read Colin Barrett, I had the sensation that my nervous system was being vigorously flossed. I still remember the inciting passage, from the 2016 story “Anhedonia, Here I Come”:

He stopped at a McDonald’s drive-through, inhaled three one-euro hamburgers and a fries and a Coke, and took a spumous dump in a toilet cubicle bathed in the purple-blue glow of UV lighting installed to prevent junkies from finding the veins in their arms.

“I can’t believe they let you write spumous dump in the New Yorker,” I told Barrett when we spoke in 2022 about his story collection, Homesickness. “We all make our little contributions to history, Naomi,” he replied gravely.

There’s a voraciousness to Barrett’s hyperliterate, sometimes lavish prose. Over the years, I’ve returned to certain stories for the sympathetic jolt of that first read: casually rococo sentences that feel on the brink of being too much, but never are. As humble as his characters may be—orphans, drug dealers, groundskeepers/part-time gym teachers—the language takes their concerns seriously, operatically, and with bracing honesty.

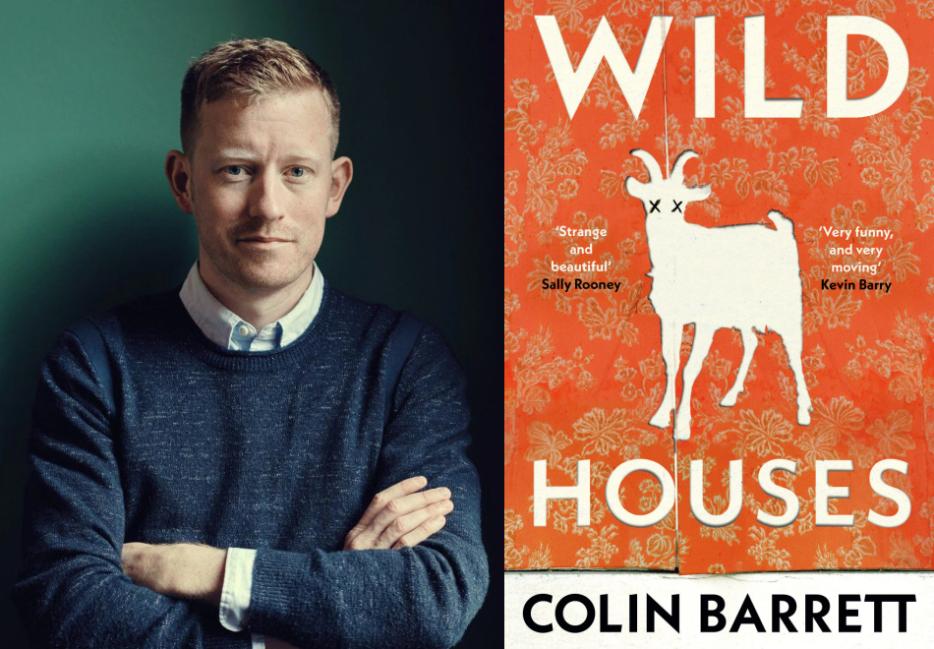

Barrett was born in Fort McMurray, Alberta, spending the first few years of life in Edmonton, Toronto, and briefly Australia, before settling in County Mayo, where he currently lives. For over a decade he’s published award-winning and beloved short stories set mostly in small-town western Ireland—darkly funny tales of close-knit but not always kind communities. His first collection, Young Skins (2013), won the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, with one story, “Calm with Horses,” adapted into a 2020 film starring a pre-Banshees and Saltburn Barry Keoghan. Barrett’s first novel, Wild Houses (McClelland & Stewart), represents a step toward something more ambitious and enduring.

Returning to the familiar setting of an interpersonally cramped Irish town, Wild Houses takes place over one anxious weekend during Ballina’s annual Salmon Festival, with locals “supping beer in plastic cups and peering out into the bright commotion of the street with glazed, red-cheeked smiles of innocent connivance.” Not that Barrett’s characters get to enjoy any of it, living by their own law within the narrowest of spaces.

It begins with the abrupt home delivery of a slightly roughed-up teen named Doll English, who “looks like any young fella you’d see shaping around town on a Friday night, punctiliously spruced for the disco.” Doll has been abducted by the disagreeable Brothers Ferdia, who impart justice their own way: by holding him hostage in the remote home of their cousin Dev. But nothing is truly remote in Barrett’s minutely observed world. Everyone knows everyone—the car they drive, the Tequila-branded jacket they wear. It makes for an uncomfortable intimacy.

The action is narrated closely by two characters so deep in the margins they threaten to fall off the page: seventeen-year-old Nicky, Doll’s quick-minded girlfriend, wordlessly grieving the loss of her parents, and Dev, a withdrawn and “godly-sized unit” also stunted by his mother’s recent passing. While Dev and Nicky never cross paths, they offer important access to the drama as it unfolds.

As in his short fiction, Wild Houses showcases Barrett’s forensic eye and ear for human detail, his compassion, and his love of a ridiculous joke. We spoke again recently to discuss some of what went into writing this extraordinarily funny, devastating novel.

~

Naomi Skwarna: You once told me that when it comes to short stories, you “write towards character.” How did that intuitive composition style meet the perhaps more technical process of drafting and editing a novel?

Colin Barrett: My first draft managed to be both over and under written, which is probably something a lot of editors find when they’re handed a first draft. All the plot points were there, all the characters were there, but some were superfluous and so I had to winnow them down. Then when I winnowed them down, some of them needed teasing out again. In the first draft, Nicky was there, but she wasn’t as integral.

What’s your technique for that winnowing process?

It doesn’t matter if sequences are good or bad. Is it entertaining or not? Are they pertinent or not? Do they move the plot forward or not? And do they make things clearer as opposed to being digressive or going off on little side trips that may not have been necessary? The big decision I made in the second draft was that everything in the town’s plot line was going to happen from Nicky’s perspective.

And then you get to know the other characters, like Doll and Sheila and Cillian, through her eyes.

Doll is a character you see different perspectives of, but from the outside. There’s the part with Nicky driving him and his mother around, which is a very important scene because you get to see him at his most relaxed and cosseted and sort of, you know, charming, if he’s capable of any charm. Whereas when he’s just with his girlfriend and his peers, he’s trying to be a little bit more macho—trying to fit in. Then he’s obviously going to be different again when he’s kidnapped and in Dev’s house.

I appreciated that you kept Dev and Nicky as the two focalizing characters through which we see the others, and how different a character like Doll can appear as the context shifts. Doll felt very knowable, but it was interesting to only learn about him through the others.

It freed me up when I realized I wasn’t going to bog the story down in the inner lives and backstory of [Doll’s] family. Instead, I’m going to have these two characters—Nicky and Dev—who are both on the thresholds of their own lives. It’s Dev’s house that Doll was brought to, but he’s still very much on the periphery of this scheme. He’s basically an unwilling participant.

Nicky as well is someone who’s on the threshold. She’s orphaned and her own brother is away and she has this relationship with Doll and this semi-familial relationship with Sheila. But she doesn’t belong to their family either. Maybe she’s not even ready to acknowledge it herself but she’s probably growing out of her relationship with Doll and getting ready to leave Ballina.

So much of writing a novel is just trying to have a degree of flexibility in the perspective, so it’s very important who your framing characters are. It took me until the second draft to figure out who that needed to be exactly. It was always Dev, but then just to winnow it down to Nicky, to complement his [storyline]. I probably should’ve worked that out a lot earlier, but—

Oh, no, no, no, I’m sorry. I hope I didn’t imply that in any capacity.

I’m castigating myself, Naomi!

There’s a leanness to the novel, but you still made space for these little micro-stories, no more than a paragraph or two, that show characters in really funny or colourful ways. I’m thinking about a part early on where you introduce Cillian through one of his crimes gone awry, describing him “curled up in agony on the ice-cream man’s lawn while the bewildered and pajama-clad ice-cream man and his wife took turns berating him.” Another one I loved is the farmer during Nicky’s bar shift who orders the jelly and ice cream. That part was so funny. It gives counterweight to the harshness of Nicky’s life, a bit softer and sillier, in the midst of everything that’s going on.

He survived every draft! I was down in a pub years ago in Ballina and there was a man, probably in his forties or so. A grown man! He was having lunch at the bar and he said “can I have a look at that dessert menu?” Took a big, long—thirty seconds of solemn, intense concentration—and goes, “I’ll have the jelly and ice cream.” Why is a grown man ordering jelly and ice cream? I mean, it’s just beautiful. The story is, in many ways, about a kidnapping, and there’s all sorts of anguish and dread going on. But you have to have those little moments in there. People who grew up in a small town, everyone knows each other. Everyone has their own lore, you know? Every family. I meet my friends that I went to secondary school with twenty years ago and everyone starts talking about “remember what that fella did?” I wanted to capture some of that. You want to keep moving forward, but to be able to pause and bring out the texture of the world is really gratifying.

Yes, all the vernacular details and the simple landmarks of a housing complex, a pub, or a river—it does so much to make me see how connected everyone and everything in town is. Regarding the jelly and ice cream: I had to look it up. I didn’t know what the heck it was.

Oh my god. Yeah, I had some last week when I was down with my mother. She made jelly. Big old translucent block of…I don’t know what it is.

I couldn’t tell if it was sort of like Jell-O or like a like a—

It’s gelatin, I guess?

I read about something called a Wibbly Wobbly Wonder—

Oh yeah.

Seems to be a famous Irish treat?

Those are really good. I don’t know if they still make them.

It looked like they were phased out in the early 2000s. People are upset about it.

They were good as hell. They had a bit of jelly on top, covered in chocolate, and then ice cream on the bottom. Beautiful! Crazy, crazy good.

Coming back to the drama a little bit—I’m curious about, well, the petty crime, Colin. You start with these guys dragging a teenager into Dev’s house, this kidnapping. In much of your short fiction, too, there are these semi-likeable lowlife characters. Some of them are genuinely bad men but mostly it seems like they’re committing relatively low-stakes misdemeanours. What draws you to these kinds of characters, these rough guys who mete out their own justice?

Where I grew up, and the time I grew up—small Irish town through the ’80s and ’90s—people had to leave the country because [Ireland] was in a never-ending recession. All through the ’80s, my entire generation, my parents’ generation, they all had to just leave. There was no work in Ireland.

I grew up in a small coastal town, which would have always had fairly high levels of unemployment. It was also a cheap place to live, and what that bred was a type of person who didn’t need much to get by, or could get by not on much. I’m talking about twenty, thirty years ago, I suppose. Older people I would have known who were adults when I was a kid. They were basically people of…miscellaneous occupation (chuckles), which just meant you didn’t have a job, you didn’t have any qualifications. They weren’t employed, but they did bits. Like they might go work on a building site for a while. They weren’t allowed to, didn’t have the qualifications. Cash in hand, seasonal jobs, working in pubs. Some of them would end up doing a lot of technically criminal activity. But their cousin asked them to do something and they liked their cousin and he’s a bit of an eejit but he’s all right, so they’ll go do that for him. It’s an informal economy.

The Ferdias seem like these types of guys, but with an unpredictable cruelty to how they operate.

The Ferdia brothers are a little bit scary. They’re not the brains of the operation. They’re not the people who would have the connections or means or wherewithal to run an elaborate drug deal. They’re henchmen. They’re a pretty low rung on the ladder, as it were.

I’ve always known a class of person like that, that were working class, who just didn’t have much in a small-town rural environment. They’d end up drifting into theses marginal occupations and opportunities that run right along the border of legality. It’s always been very interesting to me, but I don’t want to romanticize it. It occurs to nobody to call the police. These people don’t live in that world. They don’t live in a world where you call the police if you’ve got a problem. Their interactions with official Ireland, administrative Ireland, are very intermittent.

But they’re not anonymous to each other either, like how Doll and Nicky bump into Dev’s dad in town the day of the kidnapping, and he knows Doll’s father. They’re all connected, even peripherally. Everyone is somebody’s son or dad or cousin.

That’s part of the fun. Doll knows [the Ferdias]; he would have seen them hanging around with Cillian. In my small town, you’re always going to turn a corner and bump into somebody. I couldn’t exclude that factor from this story, even though the stakes, at least to Doll and Cillian and Dev, are pretty high. You can’t deny that aspect of it, which is that they’re kidnapping someone they know, and that’s why they do it. And so, there’s going to be all these complications. It’s an extremely ill-thought-out plan by the Ferdias.

The novel really is just a bunch of conversations between people who know each other, and the kidnapping is the engine it runs on. It’s about how they all know each other as a community, and there are rules in any community. Gabe Ferdia’s refrain is “he just wants to keep things civil,” or so he keeps saying.

I’ve never heard the term wild house before, or at least not in any kind of proper noun type of way. You use it to describe Cillian and Sarah’s house—that at a certain time, it had been a wild house with people coming and doing drugs and partying all the time. Is that an Irish term, “wild house”?

People have asked me the same question here. I feel like someone just said it, possibly my mother, that’s a wild house, you know? It’s certainly not a common term. It was a turn of phrase that was in my head; I don’t think I made it up necessarily. It occurred to me to put it in when I was writing that sequence, and then at the end, hunting for titles as always, it felt good, it felt right.

Last time we spoke, you mentioned a Vonnegut quote about how with a short story, you want to “start as close to the end as possible.” What would you say is different about writing a novel versus writing a short story?

I think you have to treat sentences differently. In my very earliest stories, a lot of the stories in Young Skins and several in Homesickness, there was a sort of unalloyed pleasure in language, you know? I got so much pleasure out of finding a register, moving between slightly more elevated language and then the more earthy and vernacular, throwing in local idioms, and then not being afraid to throw in your ten-dollar polysyllables as well. Sometimes stories can just be a language event.

Did you say a “language event”?

Yes, like, language is so important to a short story. The language can have an intensity because of the compactness of the form. But language in novels, it has to be different. And obviously, there’re people, you know, there’s Nabokov, and there’re all sorts of exuberant stylists who write linguistically rich novels, but I found I had to be a bit more controlled with my language—making sure it unfolded at a rhythm that would carry readers along.

That almost sounds like you were playing more to a sense of duration? Like what you were saying earlier about not wanting to bog down the plot.

There’s a certain momentum you need in a novel to bring a reader through. Unless a short story’s uncommonly long, you’re either going to start it and not finish it because you don’t like it or you’re going to read the whole thing through in one go, right? Whereas the novel, you’re probably going to read it over a few days or even a couple of weeks. There’s some sort of base rhythm—you need to have a base momentum that can survive interruption, that can survive the tension leaving it and coming back to it. That’s what I concern myself with. Especially in the drafts when I was restructuring and, as I said, when I made that decision to winnow it down to two perspectives—Dev and Nicky—got rid of all the other perspectives, tightened up the timeline. Which sounds like it doesn’t have to do with language, but it does, in some way.

You try to keep it to the scenes that are going to have all the dramatic resonances and everything in them, you know, the psychological richness that you want, but you have to have those more utilitarian passages in novels, too. You need to lean into that and make sure the thing is solidly constructed. Novels are their own thing. They’re very strange. I think lots of people who aren’t innately novelists can write really good novels.

What do you mean?

The novel is the predominant literary form—if you’re thinking poems, plays, short stories, novels—it’s the mass form. But I think there are very few born novelists. Maybe it’s just the one that requires the most conscious effort. I’m not saying poets don’t work at it! But a novel is a day-after-day construction. It’s like building a house.

[Readers] have to hold it in their head in some way. They don’t have to recall the whole thing but there has to be a solidity to it so that your attention can be removed from and returned to it. I think this is a very bad answer, but you asked me a very difficult question, in fairness. My favourite definition by far about novels is [Randall Jarrell’s]: “A novel is a prose narrative of some length that has something wrong with it.” There’s no such thing as a perfect novel. The one we love, another person will pick up and say “that was unreadable.”

I can’t believe I don’t have to write it anymore! I’ve done it. It’s published. So anyway, on to the next one. On to the next new [unintelligible]* pain.

*Neither Barrett nor the author of this interview could discern what was said here, mutually deciding that [unintelligible] was an apt substitution.