1.

According to court documents, the little girls had been planning the kill since Christmastime. The original idea was to do it at Morgan’s birthday sleepover. Twelve-year-old Anissa, a boyish brunette with long arms and a layered pageboy cut, had read online that it’s easier to murder people when they’re asleep. It was the perfect opportunity: all three of them would be sharing the same bedroom.

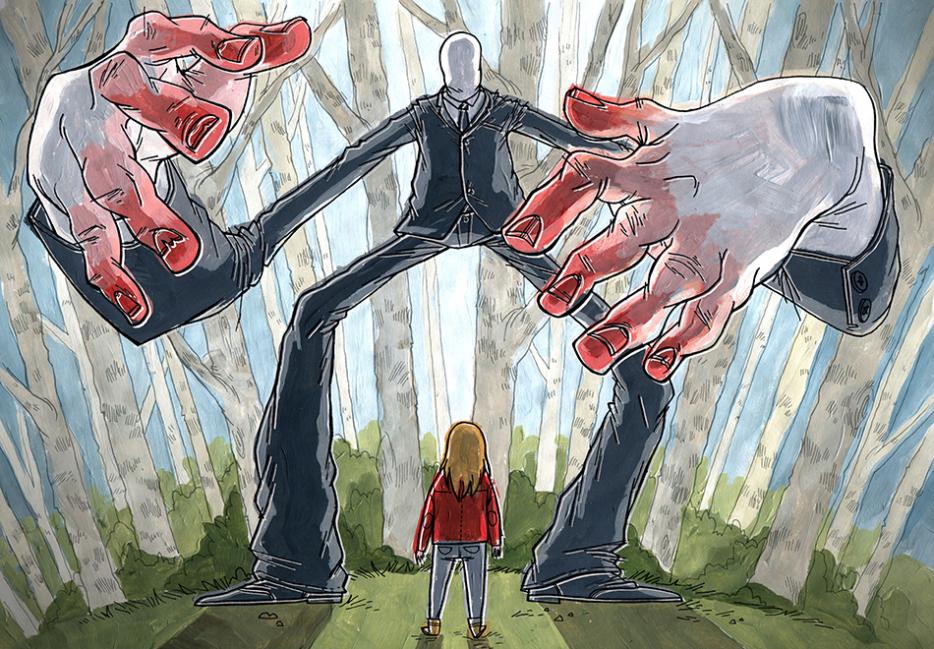

Like most suburban middle schools around Wisconsin, Horning Middle School gave its students iPads for educational purposes. Anissa’s Internet history showcased your typical online fare (bunnies eating raspberries), as well as more unusual attractions. On her Google Plus page, she Liked videos such as one in which a cat slowly beats to death a live mouse, and reposted a tutorial on how to kill someone with the wrong end of a lollipop (jam it into their eyes, their neck, all the soft spots). She also posted multiple “psychopath tests,” which she had taken and, according to her captions, failed (meaning she scored positive for psychopathy). In December of 2013, Anissa fatefully introduced Morgan to Creepypasta Wiki, a fan fiction horror website, where users can read and contribute to each other’s ghost stories. One of the most popular crowdsourced monsters on Creepypasta was called Slenderman, a tall, looming, faceless figure in a black suit.

Morgan, who wore glasses, long blonde hair, and child’s size 10-12 clothing had one other friend, Payton, nicknamed Bella to distinguish from another Payton in their class. Morgan and Bella had been best friends since fourth grade. But Slenderman stories scared her best friend, so Morgan turned increasingly to Anissa. The two lived in the same apartment complex, and grew close during bus rides to and from school. Together they pored over Slenderman fan art, doctored videos of Slenderman “sightings,” and the thousands of amateur ghost stories on Creepypasta. Gradually, they pieced together that Slenderman resided only three hundred miles away in a mansion located at the center of Wisconsin’s Nicolet National Forest. Worse, he intended to kill them, or their families, if they didn’t first sacrifice a human being in his name.

Given their options, the girls decided to kill someone, and although each would later blame the other for choosing their specific target, they decided that it had to be someone Morgan loved. So Morgan invited Anissa and Bella to her slumber party, and made a list in her science notebook that was later introduced as evidence in court.

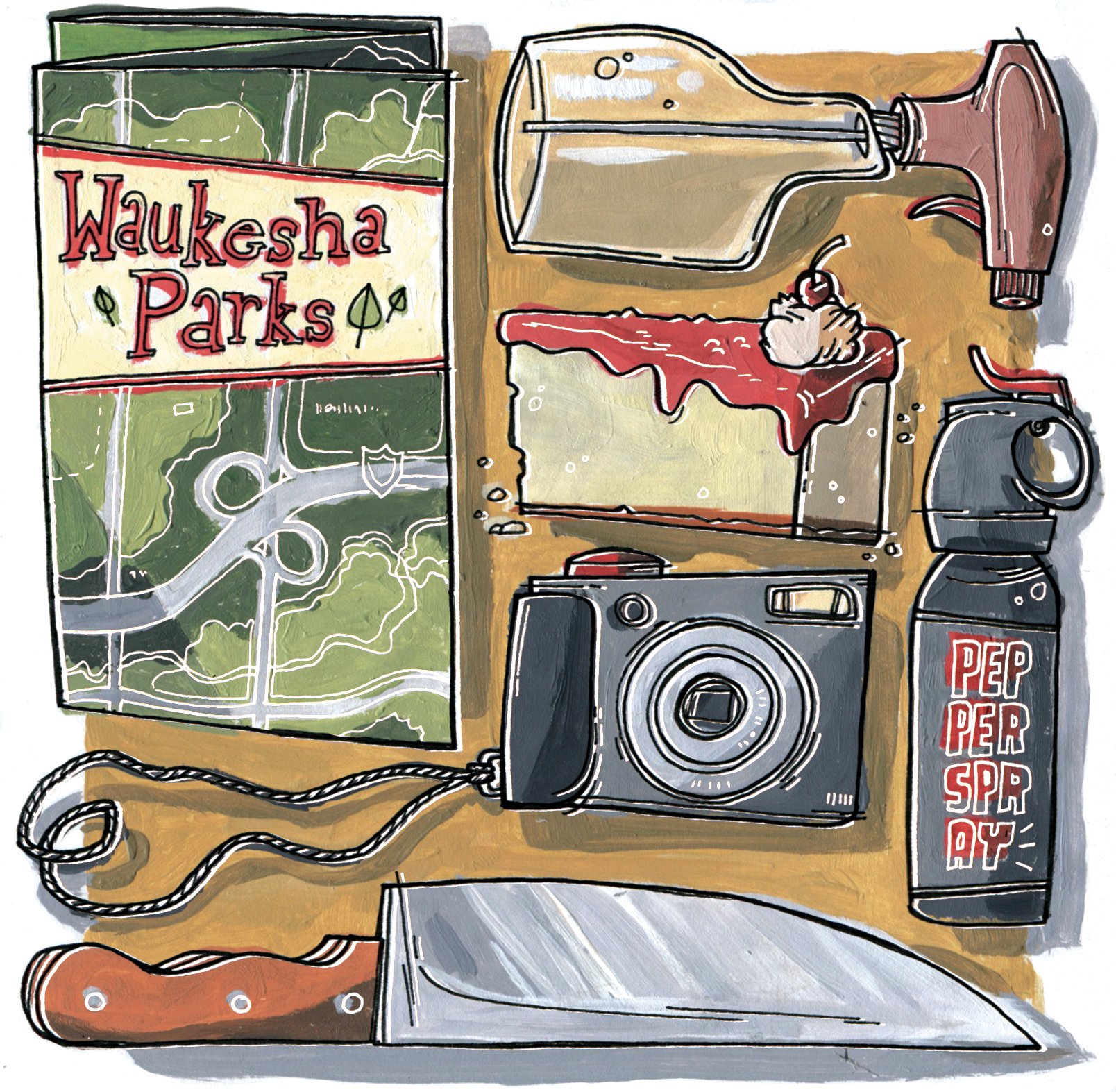

SUPPLIES NECESSARY:

PEPPER SPRAY

MAP OF FOREST

CAMERA

SPRAY BOTTLE

CHEESECAKE

THE WILL TO LIVE

WEAPONS (KITCHEN KNIFE…)

Morgan’s twelfth birthday party kicked off at Skateland, where, according to interviews with Morgan’s parents Matt and Angie Geyser featured in the 2016 HBO documentary Beware the Slenderman, the three friends laced up roller skates and rushed around holding hands, like “little girls.” Angie told me that upon returning to the Geysers’ condo, Morgan, Anissa and Bella lounged in Morgan’s loft bed, playing on their iPads, and eating cheesepuffs that Angie would later find scattered in the sheets. Anissa and Morgan’s plan was to murder Bella in her sleep, stash her under the covers, and run. But when Bella fell asleep on the floor, Morgan changed her mind. As she told Anissa, and later told police, she wanted to give her best friend “one more morning.”

The next morning at breakfast, Angie, a pretty woman with clear skin and dimples in her cheeks, set out donuts and strawberries. After eating them, Morgan snuck into the kitchen and slipped a five-inch blade into her jacket. Angie says that she and Morgan’s father, Matt, had only let Morgan go to the park without them once or twice. But it was Morgan’s birthday, so they gave permission. The sun was out and anyone knows girls are safer in a group, usually. Before she left, Morgan told her mum she loved her. Then she and Anissa and Bella proceeded to the park’s public restroom, a site prearranged by Anissa, who later explained to police that it had “a drain for blood to go down.” According to Anissa, the new plan was to stab Bella in the bathroom, prop her on the toilet, lock the door, and run away. Reverting to the notion that it’d be easier to kill Bella if Bella were unconscious, Anissa encouraged Bella to shut her eyes and go to sleep. When Bella didn’t cooperate, Anissa smacked Bella’s head against the bathroom wall, hoping to knock her out. When that didn’t work, Morgan and Anissa suggested to Bella that they go into the woods off Big Bend Road to play hide and seek. Bella didn’t want to do this either, but Morgan assured her that she could pick the next game. So Bella followed them into the trees.

According to court documents, the three girls traipsed through the brambles, and under the shade of overhanging boughs Anissa petted Morgan, who sometimes liked to pretend she was a cat. The two girls passed the knife back and forth. Morgan told Anissa she didn’t want to “do it”—she wanted Anissa to “do it.” She said, “You know where all the soft spots are.” Anissa handed the knife back to Morgan, urging her to “go ballistic, go crazy.” Morgan hesitated. “I’m not doing it until you tell me to,” she said. So Anissa took a few steps away, and said, “Now.” Morgan tackled Bella, whispering in her best friend’s ear, “I’m so sorry.”

“Then,” Bella would tell police from her hospital bed, “she started.”

Anissa watched as Morgan stabbed Bella nineteen times in the legs and torso, missing a major artery by one millimeter. Morgan punctured Bella’s lungs, pancreas, and heart. Bella shouted at Morgan, “I trusted you! I hate you!” After a while, she said, “I can’t see.” Morgan dabbed Bella’s wounds with a leaf, and Anissa instructed Bella to lie down, reassuring her that she would lose blood slower that way, and promising Bella they’d go get help, though she had no such intention. She wanted Bella to calm down and be quiet. “I don’t like screaming,” Anissa said during her interrogation. “It’s the one thing I can’t handle.” Promising Bella they’d return with help, the two girls ran away, proceeding on foot to the Nicolet National Forest to live with Slenderman.

As they walked alongside the highway, Anissa says she became disenchanted and homesick. Morgan reminded her that they couldn’t go back. This was their new life. They had brought along two water bottles and pictures of their families. Now that they’d sacrificed in his honor, they would go live with Slender in his mansion, forever. That’s when Anissa recalls she had a “nervous breakdown, and blamed Morgan for everything.”

Morgan began to pray: “Slender, if you’re listening, please help us.”

Cars whizzed by. The girls waited for a sign that things would be okay. But as Anissa later told police, no help from Slenderman arrived. No sign appeared.

“He didn’t do anything,” Anissa said. “Nothing happened.”

2.

Prior to that moment, violent crime in Waukesha was basically non-existent. Between 2003 and 2016, an average of less than one murder occurred per year (a total of eleven murders were committed over thirteen years). The police blotter records stuff like drunk dog walkers and bats found in desk drawers. When a passing bicyclist spotted Bella, lying there bloody, pleading for help, it must have felt like a horror movie come to life. The 911 operator who received the biker’s call was similarly shocked. In a thick, Midwestern accent, he sputtered, “She appears to be what?”

“Stabbed,” the caller said.

“Stabbed?”

Paramedics rushed Bella to Waukesha Memorial Hospital, where she underwent emergency surgery. Dr. John Keleman, who operated on her, told ABC News, “If the knife had gone a width of a human hair further, she wouldn’t have lived.” Her parents, Joe and Stacie Leutner, planted themselves at their daughter’s bedside. Joe didn’t know what to say at the time, he told ABC News. He remembers reassuring Bella, over and over again, “The police have them.”

Cops caught up with Morgan and Anissa on the shoulder of I-94. Their little legs had carried them around five miles into their intended three-hundred-mile hike. They were arrested, brought to the police station, swabbed for DNA, photographed, and locked in separate interrogation rooms.

Over the next few weeks, news helicopters circled the apartment complex where Anissa and Morgan’s families lived. Waukesha residents propped posterboards scrawled with well-wishing notes to Bella at the dead end where she’d been rescued.

In August 2014, two months after Bella was attacked, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker issued a proclamation that August 13th would be “Purple Hearts for Healing Day,” a state holiday in honor of Bella’s favorite color. Media outlets ran photos of Bella holding the balloons and purple cards she’d received, cropping the pictures to protect her identity. Miraculously, Bella not only survived the May 31st attack but fully recovered over the course of that summer in time to attend her first day of seventh grade. But Leutner family spokesperson Stephen Lyons says focusing on her startling recovery, and measuring Bella’s trauma only in terms of bodily injury, overlooks the inevitable, longterm psychic wounds. “When you stab a knife that deep into someone’s body, you’re going to create some pain that may stay with you forever or for a very long time,” he told me over the phone, after we’d made small talk about the unusually warm weather, which had beckoned hummingbirds to his backyard. He was referring to the scar tissue that may tingle throughout Bella’s life. “But there’s the emotional and the mental part of this healing—and often we talk more about that.” Lyons would not talk in detail about Bella’s post-traumatic stress except to say the entire family is currently in therapy.

Bella is now a freshman in high school, where Lyons says she is taking advanced placement classes and doing very well. When asked whether he thought the Leutners had forgiven their daughter’s attacker, Lyons said, “We don’t talk about forgiveness.”

3.

When Morgan was a toddler, ghosts bit her and pulled her hair. Eventually they went away, and were replaced by characters from Morgan’s favorite books and movies. Fun colors dripped down the walls of her bedroom. The oldest voice in her head, Maggie, became a dear friend. Multiple doctors would later testify that Morgan had been hearing and seeing and feeling things that weren’t there since the age of three. Matt and Angie had no idea. Aside from one night, when Morgan says she went into their bedroom, announced that hers was haunted, and they told her to go back to sleep, that it was just a dream—a night that Angie and Matt say they don’t remember—Morgan kept the hallucinations to herself.

Childhood schizophrenia expert and UCLA professor Rochelle Caplan says some children might hide their symptoms, worried parents will say it’s their imagination. Morgan’s schizophrenia remained invisible to those around her largely because, although she was quietly hallucinating and having paranoid delusions, she had not yet entered into a full-blown psychotic episode, which is much more difficult to mask.

By and large, Morgan’s pretend world remained nonthreatening. But then a man started following her. When Morgan looked into the bathroom mirror, she could see him behind her—this towering, shadowy thing, shifting in and out of corners. She couldn’t see his face, only that he was skinny, looming, the color of smoke and ink. Morgan named him IT. She hadn’t read the Stephen King novel at the time, she just didn’t know what else to call the haunting figure. IT stayed for a while, sneaking up on her in mirrors but, like the ghosts, IT eventually went away on its own, though by the time she met Anissa years later, memories of IT still frightened her.

Anissa called Morgan “Child.” She was also the only one Morgan told about the voices in her head.

When Anissa introduced Morgan to Slenderman, a thin, faceless figure who eerily resembled IT, Morgan thought she’d uncovered IT’s true identity—and over time, Slenderman fan art and doctored photographs of the Internet boogeyman replaced IT in her mind’s eye. Worried that IT would return, this time with tentacles, as depicted on Creepypasta Wiki, wearing Slenderman’s signature black suit and tie, she confided in Anissa about her fears. According to court documents, Morgan told Anissa she recognized Slender. As a young child, she had seen him with her own eyes. Anissa believed her. She told Morgan that she knew Slenderman personally. Together, they decided, they could stop him from killing their families.

Morgan was not diagnosed with schizophrenia until after her arrest, and although Morgan’s parents were shocked and devastated by the news, they were also not surprised. Morgan’s father, Matt, has schizophrenia. Matt and Angie didn’t tell Morgan about Matt’s illness because she was so young, and early onset schizophrenia is so rare. They regret that decision now. They also find themselves compulsively mining the past for warning signs, an almost impossible task, since Morgan kept her symptoms to herself. A few subtle instances stand out, though. In the year leading up to the crime, Morgan and her parents would occasionally run into people who Morgan had known for most of her life, and Morgan would act as though she didn’t know them. Angie chided her daughter in these moments, thinking Morgan was simply being “a snotty preteen.” She didn’t realize that people’s features were shifting around in front of Morgan’s eyes, making them unrecognizable. Then there was the fact that Morgan had taken to wearing layers and layers of clothing, even in springtime. That was something Matt did, too, wearing clothes that didn’t suit the weather—he wore shorts year round, for instance, even during Wisconsin’s subzero winters. Angie would later wonder whether dressing unseasonably was some kind of undocumented symptom of schizophrenia. But on the warm spring day of Morgan’s crime, when she watched Morgan leave the house wearing a heavy coat and long gloves, Angie simply thought her daughter had grown insecure about her changing body. Morgan had gotten her first period only a few weeks prior. Although the specific mechanism of hormones in triggering schizophrenia onset remains unknown, the disease’s increased incidence post-puberty presents a possible epidemiological link between growing up and going crazy.

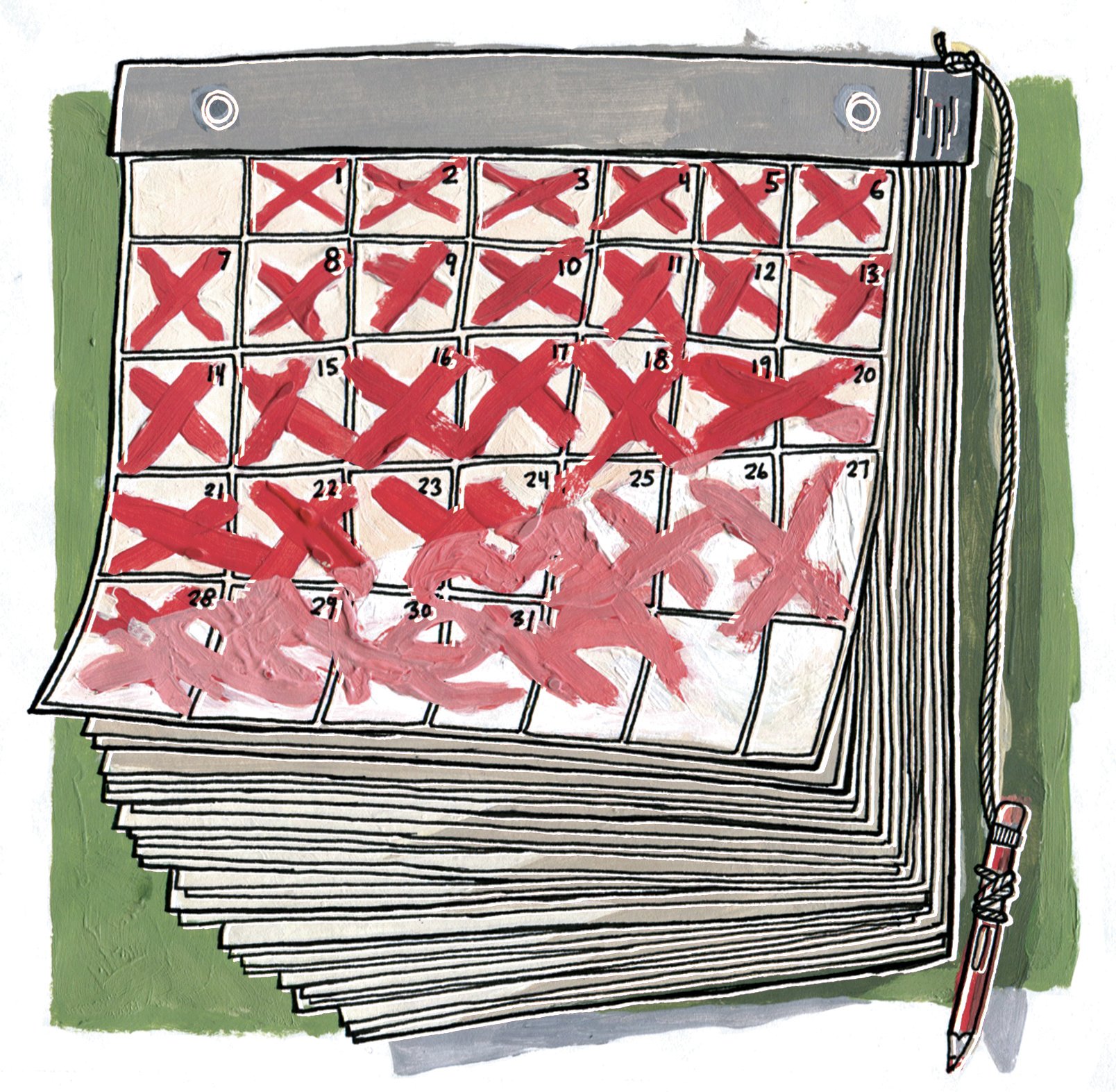

After being arrested and interrogated, twelve-year-old Morgan proceeded to the Washington County Juvenile Detention Center, a windowless facility that offers no outdoor time and prohibits physical touching between children and parents. Washington County is officially authorized as a short-term stay facility—ten-day stints are not uncommon. Morgan would remain there for more than a year.

As soon as the jail permitted Matt and Angie to see Morgan, they looked into her eyes and just knew. Morgan’s pupils were dilated, her gaze lost. “She just gave me this look,” Angie says. “‘What are you doing here, why did you come?’”

“Given the family history,” Angie continued, “I don’t know how to explain it. But…obviously she was sick. Everybody at the jail acknowledged it. It’s well documented.”

During that first visit, separated from Morgan by bars and forbidden to touch her, the Geysers watched helplessly as their daughter talked to herself, smiling at imaginary friends and laughing spontaneously, seemingly at nothing. She looked sick and disheveled. Her hair was not brushed, and she hadn’t showered for days. To her parents’ mutual astonishment, she didn’t even seem to recognize them. The symptoms she had hidden for so long were now consuming her in plain sight, and they could do nothing about it. She had been charged with attempted murder. She did not belong to them anymore.

When Matt and Angie were finally permitted to hug their daughter nearly five months later, Morgan told them she no longer liked to be touched.

4.

Criminologists have suggested that those who kill in pairs often cordon themselves into two roles: the mentally ill individual, and the psychopath. It’s a criminal profile that has been ascribed to famous cases such as the Columbine Massacre and Leopold and Loeb. In each case, those who knew the culprits would later paint one as insane, and obsessed with the other, who was sociopathic and manipulative.

But in the nearly four years that passed between their arrests and their scheduled trials, it would be the online presence of Slenderman and not Morgan’s illness that received the brunt of media attention. Even Beware the Slenderman, which delves deeper into the personal lives of the assailants than any other narrative thus far, and was the first to shed light on Matt’s mental illness, focuses on the dangers of boogeymen created by Internet. Morgan’s schizophrenia is not mentioned until more than an hour into the almost two-hour film.

At Anissa’s September 2017 criminal trial, her team would also focus on Morgan’s illness. Anissa may have called Morgan “Child” during their friendship, but in jail (where the two were kept separated, per judicial orders), Angie says that Anissa got the other girls to call Morgan “Psycho Bitch.” But when it counted, Anissa’s attorneys would successfully argue that it had been Morgan who manipulated and dominated Anissa. At Anissa’s trial, multiple psychologists testified that the girls’ collaborative Slenderman mythology ultimately refracted through the lens of Morgan’s then-undiagnosed schizophrenia to create what 19th-century French psychiatrists first referred to as “folie a deux”—or, The Madness of Two.

Dr. Gregory Van Rybroek compared Morgan’s effect on Anissa to the scientific forces that reshaped Wisconsin after Pangaea: glaciers. Anyone on the jury, regardless of higher education in geography, would have understood the reference. Kindergarten and elementary school aged children in Wisconsin spend a lot of time learning about the ice mountains that swept through the state, flattening the majority of land to the extent that hills for skiing in winter had to be built from towering piles of garbage. The glaciers also carved the famous nooks and crannies, and the rocks that resemble animals, which many families drive to see in the Wisconsin Dells, a local tourist trap built around its religiously themed main attraction, Noah’s Ark, “America’s largest water park.” "It wasn't immediate," Van Rybroek said of his perception of Morgan’s effect on Anissa, in a slight northern accent. "It was something that gradually got into her head and her friend's. They got confused about what was going on there, and morphed into the world of mental health.” Preteens wrapped together in the shared secret of Morgan’s illness, the two girls had drawn themselves into a corner—into a kill or be killed situation. “Somebody can have a paranoid delusion where they feel they’re under attack,” Dr. Stephanie Brandt, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and faculty member at New York’s Weill Cornell Medical College, explained over the phone. Brandt, who has had many years of experience working with schizophrenic children and adolescents, and as an expert evaluating children in the context of litigation, said, “…it might result in them doing something violent in what, for them, is self–defense.”

With the significant news coverage of the case, the girls’ defense teams argued that local jurors might be biased, and petitioned the judge in the case, Judge Michael Bohren, to bring in an outside jury. But Bohren refused the motion. He said Waukesha County residents could be trusted to be fair.

He scheduled Anissa’s trial first. She entered his courtroom in shackles on September 12th, 2017, and sat down beside her public defender, Maura McMahon, trembling. The chains around her wrists and ankles shook. Over the next three days, McMahon argued that although her client did not suffer from mental illness in the general sense, Anissa’s codependency with Morgan, who was mentally ill, and their shared delusion about Slenderman, nevertheless made Anissa insane by proxy “when it came time to do the deed in the woods along Big Bend road.” More often than not, McMahon spoke of her client in terms of Morgan, saying “they” instead of “she,” repeatedly highlighting Anissa’s role as an (inactive) accomplice, and implicitly underlining the argument for a shared disorder by referring to the girls in tandem. But toward the end, McMahon focused on only one of the girls, in particular, and with significant pathos—and it was Morgan, not Anissa, who provided the emotional linchpin.

“We know Morgan Geyser is a schizophrenic—has schizophrenia,” she said, “one of the most terrible and difficult psychotic disorders known to our society, one that in middle ages would have labeled her a witch and [gotten her] burnt at the stake.” She gritted her teeth, and added, “But we are not in the middle-ages anymore. We do not treat sick children that way.”

Against all odds, the jury agreed with McMahon. They came back with a verdict for Anissa of Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity. They recommended a hospital sentence of at least three years. The full length of her commitment remained in Judge Bohren’s hands. He would sentence her sometime over the winter holidays.

McMahon’s unconventional defense of Anissa—the “folie a deux” argument—had been a longshot, and the NGI verdict represented a startling departure from widespread local conceptions of mental illness as an excuse for bad behavior.

Mental illness is a controversial topic in Waukesha County. According to Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter Bruce Vielmetti, who has been actively covering the Slenderman Case since Morgan and Anissa were first arrested in 2014, people in Waukesha tend to think that “the whole insanity defense is just a joke—they don’t believe in it, even though it’s the law.” Underneath local ABC News affiliate WISN 12 Milwaukee’s Facebook livestream of Slenderman court proceedings, people commented, “It’s mental illness if the parents have money,” and, “Everyone has mental illness these days, didn’t you know?” Leutner family spokesperson Stephen Lyons has wholly rejected the NGI concept on behalf of his clients as being, at best, redundant, and at worst, dangerous. He says that anyone who tries to commit murder is by definition insane, and argues that it puts the community in an unsafe position to arbitrarily favor certain violent offenders by committing them to hospitals, where they can petition for release as early as six months into their sentence, while the rest remain where all of them belong: “behind bars.”

It remained to be seen if Morgan, whose trial was scheduled two weeks after Anissa’s on October 9th, 2017, then pushed to October 16th, would receive the same verdict. On one hand, her schizophrenia made her a shoo-in for an NGI defense, but on the other, locals had taken to social media to express outrage at Anissa’s verdict, and that made Morgan Geyser’s team uneasy. Under pressure from its neighbors, another jury pooled from the same community might issue a reactionary verdict, and send Morgan to prison.

5.

Anthony Cotton had a good reputation for defending unseemly cases. His team handled felony charges ranging from child sex crimes to child homicide, and the firm’s website promised “aggressive criminal attorneys.” Within seconds of arriving on its landing page, a pop-up appeared of Cotton’s smiling face and slicked back hair, offering to live chat. Avvo, a company akin to Yelp that rates 97 percent of licensed US lawyers, gave him a five-star, 10 out of 10 “Superb” criminal defense rating, and his services were priced accordingly.

The Geysers had never been rich. Angie worked on-call as an Advanced Neuro Diagnostics Specialist, traveling within one hundred miles of her home at odd hours to set up electrodes and machines and monitor people’s nervous systems during surgeries where there was a risk of “neurologic deficit.” She often assisted on Awake Brain operations, running the equipment and monitoring “a screen full of squiggly lines,” as she put it, while the patient lay on the table, skull open, alert and talking to surgeons. Matt was intelligent and stable, but his hard-earned mental health remained dependent on reducing external stressors, such as full-time employment, whenever possible. He worked as a stay-at-home dad, which he loved, and performed janitorial work several times a week in one of his father’s office buildings.

Cotton was expensive, but his resumé inspired hope. According to his legal profile, he had personally secured not guilty verdicts even in cases where his clients had confessed, or when the evidence against them “seem[ed] utterly overwhelming.” By the time Angie and Matt considered hiring someone, Morgan had already provided detectives with hours of detailed, videotaped confessions.

Angie told me that when she and Matt first sat down in Cotton’s office, she felt dazed, and said to Cotton that at least Morgan was only twelve. Cotton told her that didn’t matter. He explained that in Wisconsin, children ages ten and older are automatically prosecuted as adults in attempted homicide cases.

Angie wasn’t sure she’d heard Cotton correctly. Certainly, she thought, if Wisconsin harbored a law that sentenced ten-year-olds to adult prison, people would be up in arms about it. She would have heard about it in the news. There would be marches in the streets. Children could not legally vote, or drive, or drink (or, at least, they could not drink without a parent present; in Wisconsin, children are legally permitted to drink at any age, even in public, so long as a parent gives the OK). Why, Angie asked, if the law otherwise acknowledged that children behaved impulsively and were therefore too dangerous to be licensed as adults in any other way, did it treat certain “serious” offenses as grown-up initiations?

Cotton explained that unless they could secure something called a “reverse waiver”—a tricky process that, per Wisconsin law, required Cotton to convince a judge by “a preponderance of evidence” that re-adjudicating the case to juvenile court would “not depreciate the seriousness of the crime” in the eyes of the community—Morgan faced up to 65 years in prison. At that point in the conversation, Angie recalls, “There was a lot of crying about a lot of different things.”

I spoke with Cotton a few weeks after he first briefed the Geysers on what Morgan was up against. It was June of 2014. “The Slenderman Case” was sweeping headlines, Morgan and Anissa were locked away in juvenile detention, where they were separated from their parents during visiting hours by bars, and Cotton expressed some shock that everyone seemed so totally obsessed with the crime’s salacious details—the number of stab wounds; the role of the Internet; Slenderman himself. In Cotton’s mind, the more pressing question—the angle nobody seemed interested in taking—was this: Why was a mentally ill child being tried as an adult to begin with? “I’ve been practicing law for nine years, and it’s pretty clear here that something’s not right,” he told me. When I asked if he ever felt frightened by Morgan, he laughed in disbelief. “I see a very young child,” he said finally, in a scripted tone. “I see somebody who’s very, very young.”

According to University of Wisconsin Law Professor Eileen Hirsch, Wisconsin began prosecuting ten-year-olds as adults in homicide-related case in response to a mid-1990s phenomenon known as “The Super Predator.” The term was coined by then-prominent political scientist, John J. DiIulio Jr., whose theories led to sweeping legislative changes throughout the United States. In his treatise on the subject, “The Coming of the Super Predators,” DiIulio claimed to have conducted research that revealed how children raised in “moral poverty” (urban areas) were fast evolving into emotionless “wolf packs” of killing machines. DiIulio attributed the 1980s juvenile crime wave to the rise of Super Predators, and claimed that this new breed of “kiddie criminal” could only be stopped if America ceased treating them like children. He also encouraged states to “build churches,” and cited Jesus Christ as a child development expert.

When DiIulio, who went on to work for the White House, promised that juvenile crime would rise significantly if America did not punish juveniles more harshly, almost every state in the nation rushed to convert its laws. “No one has been interested, really, in trying to change that back,” Professor Hirsch told me, “to come forward with what we now know, which is that…there were never any super predators.”

Several years after DiIulio popularized the phrase, new research proved The Super Predator had been a figment of his imagination. Juvenile crime, which DiIulio claimed had been out of control, actually decreased during the mid-1990s by one third. After experiencing what he described to The New York Times as a revelation in church, DiIulio publicly apologized, but in Wisconsin, laws built in service of his debunked theory remain unchanged to this day.

Professor Hirsch explained to me that dismantling such laws proves politically tricky, in part because doing so would ostensibly require any lawmaker to first explain to his electorate that they’d had been taught to fear an imaginary evil. No one wants to hear they’ve bought into “fake news,” and so The Super Predator has become the grown-up’s version of The Slenderman: a terrifying force that must be stopped at all costs; a terrifying force that does not actually exist.

Overwhelming research published by The American Bar Association shows that children are far less likely to commit new crimes after being charged and sentenced in juvenile court, an arena that takes into consideration the child’s unique psychology, and provides rehabilitative resources customized for juvenile development. “We now operate with the understanding that a juvenile’s actions may not be the same as an adult’s—and, instead, that the juvenile might merit unique consideration under the law—and that punishment should perhaps be tailored to development and reform,” the American Bar Association states on its website. But in Wisconsin, a state that swung the 2016 election in Donald Trump’s favor by 20,000 votes, many believe in the idea that a serious enough crime is an adult-up rite of passage—and they ridicule the alternative (i.e., being “soft on crime”).

In Wisconsin, trial court judges are elected, making them beholden to the same pressures as politicians. Judge Michael Bohren catered to an extremely conservative voter base—one that firmly believed in the Super Predator-inspired rallying cry, “Adult Crime, Adult Time.” In the parking lot outside his courtroom, cars sat wearing bumper stickers that read “Police Lives Matter.”

Outsiders who report on Morgan’s crime without venturing into Waukesha have described the area as “rust belt”—a “drab” little place. In reality, the town is pristine, resembling Salem more than Gary, Indiana, or Appalachia, and its culture is much more elitist. Angie Geyser grew up on a farm in Manitowoc County, where Making a Murderer was shot, and for her, and many others, moving somewhere like Waukesha represents socio-economic advancement. The people there are educated and upper middle class. Culturally it is neither industrial nor rural nor Southern, as “rust belt” or Southern Midwestern cities tend to be. It is mannered, indefatigably friendly, puritanical, and repressive. “Waukesha County is probably one of the two most conservative counties in what now is becoming a more and more conservative state,” Vielmetti says. Referring to Judge Bohren, he added, “I think that influences a lot of his thinking.”

After Morgan and Anissa were charged as adults, their respective attorneys immediately petitioned Bohren to transfer their case into juvenile court. Despite having been officially diagnosed with schizophrenia after her arrest, Morgan had not yet received medication.

Anthony Cotton knew that his client would receive better treatment within the juvenile system, but in order to get her there, he was tasked with proving to Judge Bohren all three of the following conclusions: That moving Morgan’s case to juvenile court would not depreciate the seriousness of her crime, that keeping her case in adult court was not the best way to deter others from committing a similar crime, and that Morgan could not receive necessary treatment within the adult system. Proving the third claim would have been a slam dunk if not for a strange legal loophole that prevented Cotton from using Morgan’s mental illness in her defense during the reverse waiver phase.

In Wisconsin, attorneys can use mental illness as an argument for keeping their clients in the juvenile system, but cannot cite it as justification for moving them there. (Ironically, Morgan’s mental illness was actually leveraged as further justification for her adult status; at the reverse waiver hearing, the prosecution argued that Morgan would always be violent—an accusation that is strongly contested by experts on schizophrenia.) Cotton attempted to work around these legal strictures by presenting experts on adolescent brain development, psychiatrists and psychologists who had examined Morgan, as well as her jailers and former teachers, who described her as a good student with no history of violence or criminal activity. Cotton cited research that children prosecuted as adults have a much higher recidivism rate than children handled in juvenile or family courts. He pointed out that twelve-year-olds don’t usually consider the law before breaking it, and that scientific studies show that part of the brain tasked with processing deterrence does not even develop until early adulthood.

Before issuing his ruling, Judge Bohren sipped from a Ronald Reagan mug. He acknowledged that Morgan had schizophrenia, but reminded the court that if her case were transferred into the juvenile system, she could be released by the time she turned eighteen. At that point, Morgan would have spent half her life behind bars, and without a felony on her record, she could ostensibly pursue higher education and gainful employment. This, Bohren decided, was unacceptable. “They were young when the offense occurred,” he said. “But they get older every day, frankly.” He called the crime, “frankly, vicious,” and ruled, “on that basis,” that the case remain in adult jurisdiction. Morgan would not receive medication or any kind of mental health treatment. Following the hearing, Nick Bohr of local ABC News affiliate WISN 12 reported live.

“There were tears and some surprise here in court as a judge denied a motion by lawyers for both girls to have their cases handled in juvenile court,” he said. “The victim’s father here said they wouldn’t be commenting, though the family did appear to be upbeat following this decision.” Morgan’s father, Matt, was seen sobbing outside the Waukesha courthouse. When questioned by reporters, he said only that he wished Judge Bohren had “thought harder.”

6.

When asked how withholding treatment might affect an un-medicated schizophrenic’s mental state, child psychiatry expert Dr. Stephanie Brandt responded, “Oh my God.” Although Dr. Brandt did not examine Morgan, and was therefore unable to speculate about Morgan's specific psychiatric state during or after the attempted homicide, she nevertheless spoke with me about hypotheticals related to childhood schizophrenia in general. “We do not ever withhold medication from somebody in an acute psychotic state. It is not done,” she said. “To withhold medication is unacceptable, and it would potentiate any problems she was already having.”

On the day of Morgan’s arrest, Matt and Angie drove to the police station debating whether to let Morgan to go to the Star Trek convention that weekend as planned. They had been told their daughter was in custody, but not why. They thought they were going to get her.

In Wisconsin, police aren’t required to tell a child’s parents that the child is being questioned, or to honor a child’s request that a parent or other adult be present during questioning, unless the child specifically asks for a lawyer. Detective Thomas Casey later testified in court that he did not offer Morgan a phone call, and would not allow her parents into the interrogation room. Although she was not visibly hallucinating during her interrogation, multiple doctors would later state in court that, at the time of her arrest, Morgan had been in the grips of a psychotic episode. In Wisconsin, an entire case was once thrown out on the basis that the defendant had been going through alcohol withdrawal during his interrogation. His confession was later found to be coerced. But Morgan would not receive this leniency from Bohren.

After being interrogated, Morgan proceeded to Washington County Juvenile Detention Center, where she was allowed to make one sixty-second phone call. When Angie answered, Morgan begged her mother not to post bail. In spite of herself, Angie laughed, assuring Morgan they didn’t have half a million dollars. They were disconnected, and Morgan couldn’t figure out the collect calling system, so she did not phone home again for several weeks. The jail only allowed outgoing calls, so Angie could not directly contact Morgan—she could only call the jail and they would tell Morgan to call her back.

Due to her illness and young age, Morgan had trouble understanding the charges being brought against her. But legally, Judge Bohren could not proceed until she was competent to stand trial. So after charging her in June 2014, he dispatched her to The Winnebago Mental Health Institute, one of two state psychiatric hospitals in Wisconsin equipped to deal with “forensic patients” (formerly known as “the criminally insane”) for a competency exam. However, her lawyer says that while there, she didn’t receive proper treatment. Their only job at that time was to restore her to competency. While conducting the months-long evaluation, doctors there officially diagnosed Morgan with the disease that many already suspected: early-onset schizophrenia. Morgan was also re-diagnosed with asthma. Doctors at Winnebago prescribed her an inhaler, but not psychiatric medication. Then they sent her back to jail.

If left untreated, experts say a schizophrenic person’s mind will rapidly deteriorate, and over the next few months, Morgan became so confused that her parents noticed she was losing the ability to read and do basic math. No one wanted to be Morgan’s roommate because she acted like an unmedicated schizophrenic person. In alternating fits of loneliness and confusion, Morgan increasingly relied on her hallucinations for company.

Then, one day, another inmate suddenly offered to be Morgan’s roommate. Morgan’s family was relieved. They wanted Morgan to make real friends—that is, ones that were not imaginary. “Schizophrenics are much more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators,” Dr. Brandt told me, when I asked her what she wished more people knew about the disease. “Because of their limitations and judgment insight and ability to function, they get targeted.” In an adolescent jail of sexually starved, hormonal girls, Morgan represented easy prey. Shortly after moving in, Morgan’s new roommate allegedly began to proposition her sexually, and masturbated in front of her repeatedly. She warned that if Morgan told anyone, she would go to the press and spin the story her way.

By the time Morgan told her parents, the roommate was gone. Unlike Morgan, she was released. Nevertheless, Morgan’s team brought the allegations to Judge Bohren’s attention during another hearing aimed at getting Morgan treatment. But the district attorney’s office said Morgan was lying, and Judge Bohren believed them. “He’s clearly been in favor of the prosecution on every single thing that has been raised by the defense,” said Vielmetti.

Prior to Morgan’s official diagnosis, three separate psychologists hired by the state testified before Judge Bohren that Morgan was in the throes of psychosis and suffering hallucinations. One of these doctors stated he believed that Morgan’s apparent psychosis was her direct “entry into this particular crime,” and at least two staff members at Morgan’s jail corroborated to Bohren that Morgan was visibly hallucinating and mentally unwell. Adults would need to explain the law to Morgan for nearly half a year before she understood what was happening, and even then, her parents expressed doubts that she ever truly knew what was going on. “I still don’t understand how you can admit an untreated schizophrenic, and then four months later release an untreated schizophrenic, and call her competent,” Angie said. “She was still psychotic, she was still hallucinating and delusional, so I don’t know that I necessarily agreed that she was competent.”

“But perhaps my idea of what it means for someone to be competent is not necessarily the legal definition,” she continued, “and that can be said about a lot of things in the justice system, I think.” Sounding tired, she added, “Things that I think are right”—she trailed off—“it’s not necessarily the way the criminal justice system looks at it.”

After her arrest, Morgan remained untreated and was denied any medication for a total of eighteen months. Then, in December 2015, with Cotton’s help, Morgan’s parents discovered a Chapter 51 loophole, which allowed them to petition a judge other than Bohren, in civil court, for Morgan to be sent back to the maximum security state hospital, where she might receive treatment. This judge approved their petition, and Morgan was remanded back to Winnebago, where she was at last given antipsychotics. Upon reaching therapeutic dosages, Angie says Morgan understood, for the first time, what she had done to Bella. Memories of the stabbing dawned on her in vivid detail. She hated herself.

Morgan, Morgan’s family, and Morgan’s doctors wanted her to stay at Winnebago. But administrators at the hospital said that the intricacies of Wisconsin legislature prevented them from keeping her. The juvenile detention center technically provided a lower security environment than the hospital, and by law Morgan had to spend her pre-incarceration there. Winnebago gave Morgan a bottle of her new pills, and sent her back to jail.

Conditions like the ones at Washington County Juvenile Detention Center have been shown to drive even healthy minds insane, and without sunlight, exercise, or physical contact, Morgan deteriorated rapidly upon her return. She’d been given antipsychotics but not antidepressants, and the self-loathing that had set in upon recognizing what she’d done to Bella gnawed away at her mind. Maggie, the friendly voice who had been with Morgan longest, began telling Morgan to hurt herself. So Morgan used a colored pencil to cut open her wrists. According to Angie, staff at Washington County responded by taking away Morgan’s glasses, emptying her cell, stripping her naked, and putting her into something called a “turtle suit,” a green, padded smock. Morgan spent the next week unable to see, trying to soothe herself by singing “In The Aeroplane Over the Sea” by Neutral Milk Hotel, one of her mother’s old lullabies.

After Morgan’s suicide attempt, Winnebago overlooked whatever rules had previously prevented them from keeping Morgan, and re-committed her. Angie hesitated to say anything that might be construed as negative about the institution that had, in many ways, saved Morgan’s life. But she acknowledged that if Morgan had managed to kill herself, Winnebago would have faced a public relations nightmare—and that by allowing her back, they guarded themselves against legal issues. Legally an adult, fifteen-year-old Morgan now spent her days in Winnebago’s maximum-security adult forensic unit, surrounded by patients twice her age, who were usually violent and in a state of acute psychosis. Angie says that one day in the hospital courtyard, a small, monitored enclave where prisoners get much-needed outdoor time, another patient jumped on Morgan's back and started biting her Fortunately Morgan was wearing her signature heavy coat, so the woman didn't break the skin. But the attack left bruises. Given Morgan’s relative youth, Angie says the other primary issue has been keeping an eye on older women who wish to foster a maternal relationship with Morgan. (Violent offenders can harbor twisted notions of maternity.)

When I asked Angie if she thought Morgan and Anissa could become friends again when Anissa is back at Winnebago, she said she didn’t see that happening, given Anissa’s cruel treatment of Morgan at the jail. But she’s been told “that it’s going to be impossible to keep them 100 percent separated.”

“I mean, it’s definitely a concern, I’m sure, for both parties,” she said.

By “both parties,” Angie was referring to Morgan and Anissa’s families. But the Leutners have their own anxieties about the girls’ reunion at Winnebago. “Are they going to be able to sit next to each other and have lunch?” Stephen Lyons asked me rhetorically. “And plot again?”

Morgan is now stable and lucid. The voices are mostly gone, even Maggie, who was hardest to get rid of, is only present intermittently. She wakes up at the same time, eats the same breakfast, and attends the same rotations of daily group therapy, which includes a health and hygiene class that Morgan likes because sometimes they get to put on makeup and give each other facials. “Do you remember that movie Groundhog Day with Bill Murray?” Angie says. “That’s how life feels for Morgan right now.”

Two weeks after Anissa’s NGI verdict, Angie sat down in Judge Bohren’s courtroom for Morgan’s last pre-trial hearing. As with a wedding, the factions in this case sat divided by an aisle according to their loyalties. The victim’s supporters filled two rows of pews by the window, and across the courtroom, marooned on a bench by herself, sat the defendant’s only supporter that day: her mother. Matt rarely came to these things anymore. The last time he’d attended one of Morgan’s hearings, he wept throughout the whole thing, and multiple media outlets published photos of him crying.

As the courtroom waited for somebody to say, “All rise,” the Leutners and their guests behaved like animated parishoners in church, smiling and laughing about weekend plans, occasionally lowering their voices to talk seriously about last night’s Packers victory. On the other side of the railing, court officers were similarly casual, chuckling when the District Attorney couldn’t figure out how to turn on his laptop. Then the District Attorney started laughing, too. “As someone who works in the operating room, sometimes we do that,” Angie later told me. “Unconsciously, sometimes you do that, have casual conversation while a patient is lying there, probably terrified.” Angie stared straight ahead. Soon her daughter would be brought out in chains.

Finally, the swish and clank of shackles echoed in the hall, and fifteen-year-old Morgan entered the courtroom staring at the ground, lips parted, her hands and feet leashed to her waist by a belt, wearing shoes with white cat faces decaled on the toes. The room stood for Judge Bohren, who wore his signature bowtie—red this time, a pop of color peeking from his double chin. He glanced summarily at Morgan, who had grown six inches since her arrest. When she was twelve years old, he had sanctioned her prosecution as an adult. Now, just in time for her scheduled jury trial, she finally resembled one.

The morning had been slotted for pre-trial housekeeping issues, but in a surprising turn, the district attorney’s team and Morgan’s attorneys announced to Bohren that they had reached a plea deal. There would be no trial. Both sides had agreed that if Morgan pleaded guilty to first-degree attempted homicide, the state would take away the “deadly weapon” charge, thus reducing her potential sentence by around five years. The state would also not dispute an NGI defense. The semantic compromise sentenced Morgan to a psychiatric facility instead of an adult prison. Morgan’s family was overjoyed. By the time Bohren read the plea, they had long ago stopped hoping the law would somehow turn out in her favor. Now, all they wanted was for Morgan to be safe.

Angie told me that Morgan’s incarceration feels, in some ways, “like a death.”

“We’re taught from a very young age in our society that justice and punishment are synonymous,” she said, “and they’re not.”

But others feel Morgan received inadequate punishment. “There’s so much discussion on what’s best for those who committed the assault rather than what’s best for the victim and the community,” Lyons recently said to me. Over and over again, he has emphasized, “There is only one victim in this case."

7.

When the Slenderman case made national news, The Daily Mail swiped photos from the Geyser family’s social media accounts, publishing various images out of context to fit a story that implied Morgan’s crime spoke to ancestral evil, including pictures of Halloween decorations, which they used to intimate the family was interested in satanic rituals.

“Something I have to keep reminding myself is that the eyes of everybody else out there, you know, we’re the bad guys. Morgan is the bad guy,” Angie told me.

The plea deal had been presented to Bohren earlier that morning, and she had agreed to meet me for lunch at Taylors People’s Park, a building located in what the restaurant’s website describes as “the heart” of downtown Waukesha. Angie was in a celebratory mood, excited about eating on Taylor’s famous rooftop deck. As we climbed the stairs, she told me that despite Waukesha being relatively small, she “never really” ran into people related to the case—but then she spotted Detective Thomas Casey, the man who had interrogated her daughter, enjoying the sunshine, ten feet away. “No, we can’t sit here,” she whispered, squeezing my arm, and we retreated down the steps before he could notice her.

Forcing a smile, Angie resituated herself at a small metal folding table out on the sidewalk. “I can’t wait to not live here,” she said. “But I don’t think it’s a horrible place to live either.” Prior to her daughter’s arrest, the closest Angie had come to being in the public eye was as a teenager, when she played Consuela in West Side Story at the Community Theater in Manitowoc, a secluded, Northern town covered in lakes and green trees. Since May 31st, 2014, she had opened the door to find herself blinking against the blinding lights of local news crews. She and Matt received phone calls and hate mail, some of it generic (“that little bitch”), and some of it scary (“someone’s seriously gonna kill her”). Vielmetti told me that when the news broke, “law and order oriented” individuals in Waukesha thought the Geyser family, as a whole, should be punished, though the public view has evolved. Over salad at Taylors, Angie said she’s not surprised that people often blame her and Matt for what Morgan did. Speaking about school shootings, Angie says she always thought, “How did their parents not know that something was wrong?”

“Well, you know,” she said now, quietly, “it turns out sometimes you just don’t know.”

The media circus inspired by Morgan’s crime has died down over the past three and a half years. Aside from Bruce Vielmetti, few publish updates on the case, and when they do, they tend to source directly from Vielmetti’s work, creating a derivative news cycle. But Angie still finds herself compulsively scouring comments sections to see what people are saying about her daughter. Sometimes she’ll recognize a name or two: this or that woman she’s seen before in the school pick-up and drop-off circle. In many people’s opinions, the Internet had been as much of a culprit in Morgan’s crime as Morgan or Anissa was, and now, here was Angie, similarly using social media as a sort of self-destructive tool.

Angie told me she visits Morgan at Winnebago Mental Health Institute several times a week. The roundtrip takes about four hours, for what amounts to forty-five minutes with her daughter, and she likes to get there extremely early, to avoid being even one minute late. “I don’t know what to say half the time,” she said in a small voice, smiling again, reflexively. “There’s no parenting manual for this.” Due to maximum-security protocols, Morgan meets with her mother in the hospital cafeteria, and Angie has never actually seen the ward where Morgan spends her days. “Typically, toward the end of the visit, she starts clock-watching.” Morgan will count down the minutes left in their visit, and then begin to cry. “She just wishes she could come with me,” Angie said. “She just wants to get in the car with me and drive home, and I want that, too, more than anything in the world.”

The first time we spoke over the phone, Angie was lugging a cat carrier around a gas station nearby Winnebago, wiling away time until visiting hours began and she was able to go see her daughter. She was searching for a sick-looking feral kitten she’d seen the last time she was there. Angie grew up on a farm surrounded by animals. Her plan that day was to wrangle the kitten and take it to an emergency vet before going to see Morgan. The little cat had run away a few times, but Angie was determined that the naughty animal be treated well. “I can’t rescue who I want to rescue,” she acknowledged quietly. “So a kitten will have to do for now.”

8.

Before issuing a verdict on the plea deal, Bohren planned to address Morgan for the first time in open court. In the three and a half years that had passed since sanctioning her prosecution as an adult, Bohren had never spoken to her directly, and she was terrified at the prospect of conversing with him, particularly in front of so many people. She mentally spun through every imaginable scenario, anxiously attempting to forecast Bohren’s potential statements, questions, and her hypothetical responses. Winnebago limits its patients to ten minute phone calls every hour, and in the days leading up to that hearing, Angie heard from Morgan nearly a hundred times. She reassured her daughter endlessly, but it would turn out that Morgan was right to be afraid.

Outside the courthouse that day, the American flag waved at half-mast to honor the victims of the recent Las Vegas massacre. The Leutners and their guests sat down wearing Harley Davidson jackets, and moments later, Bohren told Morgan to rise. He asked her to describe the moment, just prior to the stabbing, when she had tackled Bella. He specifically wanted to know how she had straddled Bella, and where her legs had been, and where Bella’s legs had been. Morgan hesitated, and Bohren seemed disgruntled. Cotton, appearing confused, jumped in to explain that Morgan’s medication and overall condition made it difficult for her to remember much of what had happened in the woods off Big Bend Road, much less such minute physical details.

“Then tell me what happened,” Bohren said to Morgan.

She responded quietly, in a soft, high-pitched voice. “I hurt Bella.”

“We call her ‘PL,’” Bohren corrected her, referring to Bella’s—Payton Lautner’s—true initials.

“I hurt…PL,” Morgan whispered.

“Alright, so what did you do?” he asked impatiently.

“I stabbed her,” Morgan said.

Bohren pressed her for further information. Morgan blinked at the floor. Her wrists were handcuffed and leashed to her waist by chains, which made it physically awkward to wipe her own eyes.

During Anissa’s 2014 interrogation, she had described Morgan as “not one to cry very often,” and when asked by the prosecution later that year whether Morgan had wept during her interrogation, Detective Thomas Casey had testified that “there was no emotion from [Morgan] at all.” But now, as Morgan struggled to tell Bohren what he wanted to hear, she sobbed through every word.

She asked Bohren to repeat his question.

“I’d like you to tell me in your own words what you did on May 31st, 2014. What happened between you and Payt”—he stopped himself, annoyed, and repeated the question, this time using Payton’s initials.

Morgan told him that she and Anissa had taken “PL” into the forest. “And I said we were going to play hide and seek,” she continued. “And Anissa said she couldn’t do it, and that I had to.” She trailed off, breathing raggedly, overtaken by childish, quaking sobs.

Bohren glanced at the clock on the wall. He offered Morgan a minute to catch her breath, and told her, smiling at his audience, that they had all afternoon to wait for her answer.

After some heavy breathing, Morgan responded, “I tackled her and I stabbed her."

“Well, tell me about the tackling,” Bohren said. “How did you do that.”

Like so many of Morgan’s statements that day, what she said next came out in the form of a question: “I came up from behind her and I jumped on her?”

“And then what happened?” Bohren asked.

“And then I stabbed her?” Morgan wailed.

Bohren continued to ask Morgan to confirm details of the case, and she responded in the affirmative, with that same questioning tone. He shook his head. “So then when she’s on her back, how did you stab her? How did you do that?” As he waited for Morgan to answer, someone’s phone dinged with a notification. The courtroom remained quiet for a long while, except for the sound of Morgan’s crying. Finally, Morgan said, “I stabbed her with the knife I had taken”— another person’s phone dinged—“from my house earlier that morning.”

Bohren shifted in his seat, looking antsy. “Now, when you say you stabbed her, were you somewhat straddling her?” When Morgan didn’t answer to his satisfaction, Bohren suggested that maybe if Morgan read Bella’s account of what might have happened, she would be able to speak in greater detail about the event.

“I haven’t read the complaint since I was twelve,” Morgan replied softly.

But Bohren was unrelenting. “How did you do it?”

“I…I stabbed her with a knife,” Morgan repeated.

“And what part of her body did you stab her?”

She paused before answering, “Everywhere.”

Every time Morgan finished her description of the crime that afternoon, Bohren seemed to want her to start over at the beginning. Like her schedule at the maximum security hospital where she now lived, their conversation had veered into Groundhog Day territory. “She was in so much pain, and I just wanted to jump up and tell him to stop, to leave her alone,” Angie says. “Haven’t you heard enough?”

After Bohren officially approved the plea that day in court, the Leutner family released a statement through Stephen Lyons that conveyed their grave disappointment over how this case had turned out. “The current legal system does not favor victims in this situation,” they wrote. Angie responded to the press release with stunned confusion. “From my perspective the justice system has failed my daughter,” she said. “My daughter is the one who’s been failed by the justice system. I mean, being tried as an adult for something that happened when she was twelve?” She laughed softly, trailing off. After a long pause she added, “I still can’t wrap my brain around it.” On behalf of himself and his clients, Lyons said firmly, “We want the max for Morgan.” He explained that the Leutners plan to continue attending every one of Morgan’s hearings, and that each time she petitions Judge Bohren for release from the hospital, Bella’s parents will sit watching from the front row. “They feel strongly that they have to go and say, ‘Please do not let this attempted murderer out on the streets,’” Lyons said. "Shopping for homecoming dresses leaves only a few options because far too many dresses will show off her scars,” Bella’s mother, Stacie Leutner, lamented in a victim’s impact statement reported by ABC. “Beach vacations are harsh reminders that swimsuits aren't made for young girls with 25 scars.”

Angie thinks the Leutners, her former friends, might have reacted differently to the plea had they known what Morgan’s life was like in jail. “They never saw her in that psychotic state, so they don’t know what that looked like,” she said.

Technically, once Morgan officially begins her sentencing at Winnebago, she can petition for release every six months. “Which means we’ll petition until she comes home,” Angie said, as we finished up our lunch at Taylors. She modestly rolled up her sleeve to reveal a lily of the valley, tattooed prettily on her upper arm—for Morgan. “It’s a flower from her birth month. And it supposedly symbolizes a return to happiness.”

9.

America’s focus on Slenderman’s role in the stabbing recalls our eagerness to blame videogames for the Columbine Massacre, to blame detective stories for the Leopold and Loeb murder, to blame heavy metal music for the West Memphis Three’s alleged crime, and to blame historical romance novels for the Parker-Hulme killing in New Zealand, which Alex Mar recently linked to Morgan and Anissa's crime. Last week, Sony Pictures released an official trailer for its upcoming movie, Slenderman, a fictional horror film about the character that doesn’t touch on the Waukesha incident. Following local outcry, CBS reported that several Wisconsin theaters have pulled the film, concerned about what it might do to impressionable young minds.

It’s convenient to blame Morgan and Anissa’s violence on our newest paranoia: “screen time,” and the effects of unmonitored Internet access. Every new generation’s chosen amusements inspire parental confusion, a self-conscious bewilderment that defensively transmutes into horror. Today, technology is that new horror, screens are that new horror. But looking to Slenderman, our newest version of the Pied Piper, for explanations about Morgan’s behavior is part of that same elderly notion that what confuses us must be evil, and our inclination to demonize technology rather than discuss mental illness represents a scab on a much deeper, necrotic wound, one that needs to be explored in order to be cleaned.

Ultimately, the most striking difference between all the aforementioned murderers and Morgan is that unlike Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, or Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme, Morgan Geyser did not kill anyone. The most striking similarity? All four cases involved a mentally ill child whose incomprehensible actions were ascribed to bewitchment, possession, some soulless evil that might be stopped if only the world around us stopped changing.

10.

If Morgan had gone to trial, and had been found NGI, she probably would be looking forward to a much lighter sentence than she currently faces. But in order to secure an NGI, her attorneys would have had to prove in court that Morgan did not know at the time of her crime that it was wrong or she wasn’t able to conform to the law even if she did—a tall order, given that Morgan herself admitted, on tape, albeit in the throes of psychosis, to understanding she could “rot in jail” for what she’d done. Ultimately, Morgan’s family simply did not want to roll the dice and risk a guilty verdict, which could have sentenced Morgan to up to sixty-five years in an adult women’s prison, where she would not have received mental health care. So, they took the prosecution’s deal, one that Lyons said his clients warmed to because they “wanted to bet on the sure thing, and the sure thing is to keep [Morgan and Anissa] locked away.”

Several weeks ago, Judge Bohren sentenced Anissa Weier, as an accomplice in an attempted murder, to twenty-five years in a psychiatric facility, the maximum possible in this type of case. After three years, she can apply for supervised release. Morgan will have a sentencing hearing on February 1st to officially determine the length of her commitment to Winnebago. The state is asking for a maximum of forty years, a sentence that co-founder, deputy director, and chief counsel of the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia Marsha Levick calls “absurdly long,” and “a ridiculous response.” How long Morgan actually serves, like so many aspects of her case, is up to Judge Bohren. As soon as she is officially commited to Winnebago, Judge Bohren could release her in six months, forty years, or if he feels like it, never. If he retires, or dies, another judge will take over—an elected official, beholden to the same community that currently believes Morgan has not been duly prosecuted. As one Wisconsin resident put it, “We think she got off scotch [sic] free.”

“She was very sick and we didn’t know, and she wasn’t treated, and something terrible happened as a result of her illness, and now she’s better,” Angie said the first time we talked on the phone. “It wasn’t her, I mean, when it comes down to it, the person who did that, that wasn’t Morgan.”

As we spoke that day, Angie spotted the kitten she’d come to save and cornered it. But then an adult cat emerged from the shadows and stepped protectively between them. The relationship between the two felines was clear. So, Angie returned to her car empty-handed. Sick or not, she thought, the kitten belonged with its mother.