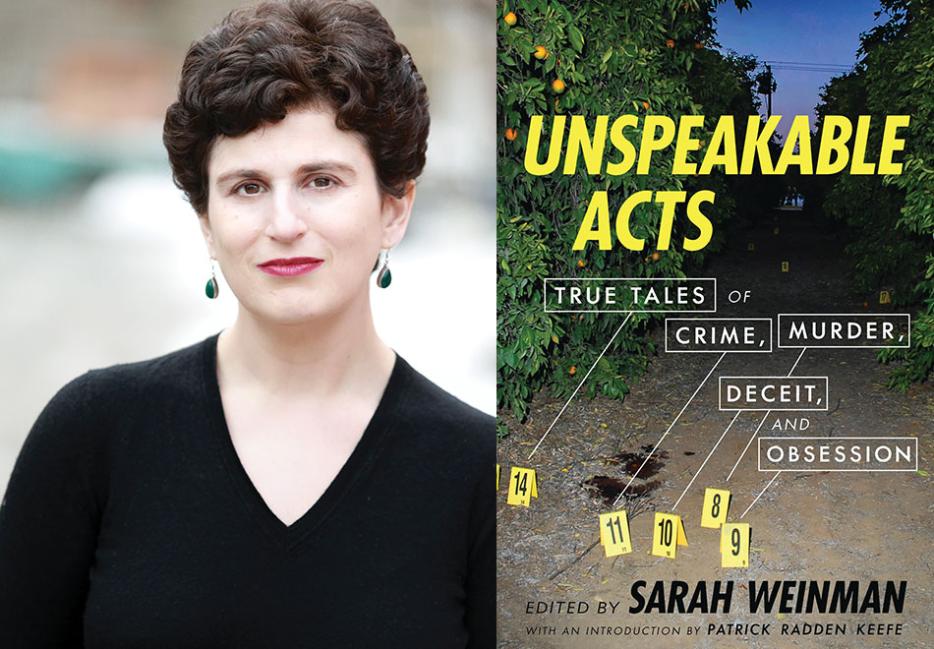

Halfway through Unspeakable Acts (HarperCollins), the new anthology of true crime writing edited by Sarah Weinman, I saw myself as clearly as if I were looking in a mirror. In Alice Bolin’s essay “The Ethical Dilemma of True Crime,” the Dead Girls author identifies a dichotomy in true crime lovers: “There are people who consume all murder content indiscriminately, and another subset who only allow themselves to enjoy the ‘smart’ kind. [...] The prestige true-crime subgenre has developed its own shorthand, a language to tell its audience they’re consuming something thoughtful, college-educated, public-radio influenced.”

I’ve never thought of myself as a lover of true crime. I would not even list it in my top five favourite genres. Yet I know exactly what Bolin is talking about, because I have watched and listened to nearly all the programs and podcasts she means: Criminal, OJ: Made In America, Wild Wild Country, The Jinx, Making a Murderer, the list goes on and on. I love these types of programs. I’ve downloaded and binged them and lost hours googling their details. But I’ve never really thought of them as “true crime” stories—or myself as a “true crime enthusiast.” Instead, I just think of them as stories, and myself as a viewer, neutral. This is no accident. In this kind of “highbrow” true crime, Bolin says, “the stance of the voyeur, the dispassionate observer, is thrilling without being emotionally taxing for the viewer, who watches from a safe remove.” As a white middle-class person who has never really experienced the direct interference of law enforcement in my life, these types of stories provoke my curiosity without ever forcing me to wrestle with the moral implications of my interest, or their addictiveness. They encourage my natural inclination, which is not to ask too many questions—of them, or of myself.

In Are Prisons Obsolete?, Angela Davis explains that media images of prison have “become so much a part of our lives that it requires a great feat of the imagination to envision life” without the carceral system. The ubiquity of the prison allows us to imagine it as a natural feature of the world like any other, something that cannot be changed or gotten rid of. It is this kind of imagined neutrality that allows many of us to accept and uphold oppressive systems without questioning them. As a genre that frequently relies on and repeats the same kinds of themes and structures (beginning/middle/end, good/evil, success/failure, victim/perpetrator, good cop/bad cop), true crime has historically played a major part in solidifying and entrenching our cultural conceptions of crime and punishment. No matter how much I understand about corruption or misconduct, the foundational elements in the true crime stories I consume often feel fixed, unquestionable: cops, jail, the legal system, all parts of a conveyor belt the real human “characters” in these stories travel along from beginning to end.

But true crime is also a genre uniquely positioned to complicate and ultimately dismantle these perceptions. The pieces in Unspeakable Acts explore this potential; they examine the ways in which carelessness, bias or built-in systemic discrimination in the criminal justice system fail victims and perpetrators alike. They talk about what bullets do to bodies, what border agents do to immigrants, what police do to people, what parents do to children, what children do to each other. The book is tonally, stylistically, and thematically diverse.

There is also not a single Black author in it. Only one of the contributors, Karen K. Ho, is not white. In a country whose prison system is a direct lineal descendent of the slave trade, in an era where Black writers like Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah and Wesley Lowery win Pulitzer Prizes for crime reporting—and in the midst of a fresh and roiling pop-cultural awareness of the inherent white supremacy of law enforcement—it seems like a glaring oversight for a book that wants to demonstrate the expansive potential of true crime writing.

Weinman is aware of this problem. She wrote a piece in BuzzFeed that came out just before Unspeakable Acts was released; she also tipped me off to Elon Green’s recent published piece about “The Enduring, Pernicious Whiteness of True Crime.” Throughout our conversation, she was eager to talk about her anthology’s shortcomings as well as its successes. She sees the book, she told me, as a kind of link between true crime’s past and what she hopes will be its future.

Emma Healey: I really appreciated this book for the way that it worked to expand my understanding of what true crime can do.

Sarah Weinman: I feel like you can’t—or I can’t—put together a collection or a book if I don’t have some kind of underlying argument, or reason for people caring. There had been earlier true crime anthologies; there had been a series called Best American Crime Reporting, which collected the year’s best in true crime. What I concentrated on was mostly that it was, like so many genres, male-centric and very white. True crime is an inherently white genre, which I’m hoping will change. It hasn’t gone far enough.

Looking back to how popular Serial was, and how it opened the door to people who, perhaps like yourself, didn’t think of themselves as consumers of true crime... they weren’t aware that true crime is a really elastic, even nebulous genre. Which is generally what I think of all genres, that they’re very porous and they’re in conversation with other genres and that everything is sort of this big soup. That’s better, because it allows for all sorts of different ways of telling stories, or shifting focus and perspective.

I remember reading Alice [Bolin]’s piece right around the time it came out, and almost cackling. I just thought, Yeah. We need somebody to interrogate this really close to the bone. I also gravitate more toward “highbrow” true crime, but I think it’s also important to recognize that there are traps in those types of programs and books and podcasts and documentaries. Just because it has a sheen of “respectability” or broadening narratives doesn’t mean that it’s not falling into all the same traps that traditional true crime is falling into.

It seems to me as though true crime can be very much used to either pick apart some of these oppressive systems, definitions of “crime and punishment,” the carceral system, all that stuff. But, also, it can be used to reinforce those structures.

It can absolutely be used to reinforce those things. And I think that certainly in the last few months, with protests and the various calls to defund police, [there’s a need] to figure out, “Well, who’s the carceral system for? And who is actually benefiting from the way that the criminal justice system is working or mostly failing to work? And who is not just not benefitting but is being absolutely failed by the way that the criminal justice system works?”

Obviously in Canada there’s been so much talk about how to address proper reparations to First Nations. That’s gone to some degree, but clearly it cannot go far enough, because the harm that was done was just orders of magnitude more than we’re able to comprehend. It’s the same thing in the States, with respect to Black and brown and other persons of colour. But especially Black people. We have 400 years of slavery that has to be reckoned with. The way that police were set up, which was essentially to enforce white supremacy… you can’t just snap your fingers and undo it. These are gigantic questions, and the structure of true crime storytelling has often not been well-equipped for addressing those gigantic-picture ideas. But in order to properly reflect what is happening in the world, we have to at least try.

There are those more explicit ways that the genre can be set up to elide or ignore the complexity of a lot of these issues. As you mention in the book, people are attracted to a narrative that has a beginning and a middle and an end, certain tropes or types of characters. That is a thing the genre can be drawn towards repeating, that makes it sort of binge-able. But, also, there are less explicit ways that true crime can reinforce those structures, like how a story often has to go through certain channels before you can write about it. There have to be official documents, or transcripts, or people who have gone through the criminal justice system before you can report on what has happened to them. There are some very successful examples in this book of people critiquing those systems as they report on them, but to be writing about these systems and to be working inside of them and also to be actively working to deconstruct them at the same time… it seems like a difficult transition for the genre to make.

When you take real-life trauma and pain and transform it into a story, what gets left out? Often, it’s the messiness. Let’s say you are a victim of sexual assault, or your family member was murdered. That is an abrupt thing that occurs, that act of violence, but the ramifications last often for the rest of that person’s life. And yet they still live, and they still have to function in the world, and sometimes they function quite well, and sometimes they don’t, and sometimes they do both at the same time. It’s this nonlinear way of living that I don’t think is necessarily reflected in a lot of true crime storytelling.

I think it’s a little bit more reflected now, especially in modes of story that aren’t necessarily wedded to a neat and tidy ending, or they might live in the uncertainty a little bit more, or that focus more on the person to whom the worst thing has happened as opposed to the narrative put forward by law enforcement. Because as we continue to see over and over again, the inherent structure of law enforcement and the criminal justice system doesn’t really do a lot for people who are victims of crime. If anything, it can retraumatize them. The nature of interrogations can lead to the wrong person being arrested and spending many years in prison for a crime they may or may not have committed. I also think there hasn’t been enough focus on judges and how they’re frankly not necessarily equipped to deal with humans in administering the law. True crime is this conflict between what the law is supposed to do and isn’t doing, and humans and their understandable emotional needs, and damage. It’s this collision course, and sometimes worse things emerge from that as opposed to better ones.

There was a conversation, I think it was the event that I did at Calgary Wordfest with Karen K. Ho, who was one of the contributors. She had brought up that while she was working on the story that became “Jennifer Pan’s Revenge,” having never reported out true crime, she didn’t really know what the tropes were. But it also meant that she didn’t necessarily get the access to court and to the cops that more traditional crime beat reporters might have. I think that was for the better, because the focus was more on the family and people around the family, and her own experiences in the community. And frankly, those are stories that haven’t been told enough. We need more of that.

What do you think needs to happen for true crime to become an expansive and flexible genre that works to critique these systems and center the stories of victims and the people who are oppressed by them? And do you think that will happen? Given the way things are now, the “true crime boom” that’s been building over the past few years, and the [ways] people are currently rethinking their relationships to these systems, do you think things will change, or go back to the status quo?

The true crime industrial complex is really stubborn and hardy. That’s why [in the book’s introduction] I say that true crime has basically been in a moment for centuries, because humans have always been fascinated by blood and gore and extreme behaviour, and people doing the worst possible things that they can imagine. Like, I love what Dateline does, and what 20/20 does, but they have a certain genre formula and I don’t see that changing. They’re not suddenly going to become much more enlightened.

But I think representation everywhere is a constant source of conversation and hopefully change, and that has to happen in true crime as well. That was why I wrote the BuzzFeed piece. Because in the wake of the recent protests, I was looking at Unspeakable Acts and just really being brought home that there’s one nonwhite writer and no Black writers. When Black creators get a chance to tell crime stories, what kind of stories are they telling? The more that we have crime stories that reflect the communities who are most impacted, written and produced and created by the people who are most impacted, I think that it will just lead to [the kinds of] stories that are missing right now. If I, a white lady, want to pursue a story involving Black victims, it means that I have to gain the trust of this community. Not that it’s impossible, but they have no reason to trust me, the interloper, in a way that they might be more forthcoming with someone who is part of that community, and understands things that outsiders can’t.

In that BuzzFeed piece you mentioned Serial specifically—how it handled its subject very differently than other things like it had done in the past, but also how it was really missing a key understanding of the communities and the cultural nuances at the heart of the story. That’s an interesting thing about the genre as a whole. You can be critiquing the system, seeing part of it for what it is, and missing this whole other crucial aspect of it at the same time.

As a journalist I really try hard to be as morally culpable as possible, because, as I’ve said on more than one occasion, I’m essentially contacting someone or cold-calling them or trying to get in touch with them to spill their guts about the worst thing that ever happened to them. And in order to do so I can’t just go in like some callous, parachuting whatever, because they’re gonna clam up. And frankly, why should they tell me anything? I’m not entitled to their story, and no one is [required] to share anything. It’s really important that I keep that in mind, and also just try to be as open and transparent and clear about what may happen if they talk to me, and what could happen if the piece publishes. You can never predict everything and anticipate everything, but we live in an age where everything is even more under scrutiny the moment it’s published, and to not walk sources through that is, I think, a real problem.

You talk in the book about the ethically thorny proposition of consuming true crime. Do you feel like writing it is also an ethically thorny proposition?

I think they’re connected. I mean, I don’t think you can necessarily divorce the writing or the creating of true crime from the consumption of it. I’ve been fascinated by crime since I was a little girl. I would read up on unsolved murders of sex workers in my hometown, or the murders of girls in and around eastern Ontario that we now know were committed by Karla Homolka and Paul Bernardo. To know that Kristen French and Leslie Mahaffy, among others, were very close to my own age… there’s this identification with the victim. That’s something you do. But what does that actually mean, to “identify with the victim?” Is it real identification, or are you just creating some artificial link between yourself and these girls?

These are just important things to come into. To be mindful that, yes, you’re trying to be as ethically sound as possible, but journalism itself is an ethically thorny enterprise. Anytime that you turn real life into a story and it becomes closer to entertainment, there are always going to be these pitfalls. You might not be able to avoid them, but I think that awareness is always the first good step.

What’s it been like for you, as someone who has been interested in true crime from a young age, to watch the evolution that’s been happening over the past five or six years as it’s moved into the mainstream?

Like with everything I’ve become fascinated by that at first seemed like only a secret to me or a handful of people, once it becomes more “mainstream,” you become a lot pickier about what you consume. So, yes, I’ve probably listened at least in part to most every true crime podcast, but most of the true crime podcasts out there are not necessarily all that good. But that’s also a function of, I’m a journalist, so I’m going to gravitate more towards those that are reported with rigor and care and empathy, and that have real investigative chops behind them, as opposed to the podcasts where, you know, just a couple of people are talking.

That said, one of the contributors to the anthology, Sarah Marshall, co-hosts this amazing podcast with Michael Hobbes called You’re Wrong About, where, yes, it’s two people talking, but the level of research and understanding and flipping scripts is so key. If someone wanted to describe Unspeakable Acts as You’re Wrong About: The Anthology, I wouldn’t put it past them. It’s part of the same overall conversation: rethinking things we thought we knew and seeing them in a different light. My hope is that if there ever is a follow-up anthology or some kind of collection, it would reflect the moment that we’re currently in and all of the conversations that we’re having and continue to need to have, and that the representation is a lot more accurate. I suppose that the collection that I put together is a bridge between how we saw true crime before and how we have to see true crime in the future.

[Marshall’s piece, “The End of Evil”] felt like an excellent example of that. It really took something that I thought I knew the story of, and then dug deep to figure out what was actually going on inside of it. I thought it worked really well as a bridge inside the book from one side of it to the other, from the more narrative pieces to the bigger, broader ones.

Structuring an anthology is always tricky in terms of what pieces should go where, but I felt like, with this one, I always knew that it had to have that three-part structure. It’s like, “Here are the traditional, excellent longform narrative stories. Then here’s the section where we talk about what true crime is supposed to be doing and how we narrate it and how it should make us uncomfortable.” And then it really opens up in the last section, just rethinking how we even see true crime, and what additional stories we might not necessarily fold into the genre, but we should be folding in.

To go back to Sarah’s piece, until I read it I was massively disinterested in anything to do with Ted Bundy. Just because there was already so much that had been written or televised, and there were podcasts…. that [piece] was a trapdoor into seeing what happened in an entirely different way. Looking at the stories of the people who were harmed and decentralizing the myth of the serial killer. I wanted a story where we were talking about the American fascination with serial killers, but in a way where the script, again, was flipped.

Something I kept seeing in the book was that anytime a person in any of these stories thinks of themselves as purely an observer or a bystander, they’re actually directly implicated. Like the people in that piece who come out to watch Ted Bundy’s execution. Or in [Rachel Monroe’s piece about a romantic scammer, “The Perfect Man Who Wasn’t”], where she gets tricked by the same man who scammed the victims she’s been reporting on. It seemed directly related to the way that I, as a white woman, have often thought about stories about crime and punishment. I think of myself as an observer when I’m actually directly involved in these systems.

There’s so much magical thinking related to how we’re supposed to take in true crime. This idea of, I need to consume this story so that if something like that happens to me I’ll react differently. That’s a real problem because it assumes that somehow, whether you realize it or not, there’s some kind of inherent moral superiority in your reaction versus the person who an awful crime was committed against. Like, they’re suddenly worse on the behaviour scale than you are? No. So much of it is dumb random luck. I never think that I’m better than someone just because I haven’t been violently attacked. And frankly, all you have to do is look around, when one in three women have been victims of some kind of sexual assault. Everyone is in the same boat, there’s no moral superiority at all.

So many of the most famous stories about serial killers often involve white women victims who are attacked out of nowhere, when actually the reality of crime is that many of the victims and also many of the people who are disproportionately arrested and charged with crimes are not white. As a white woman who has consumed those narratives, I’ve noticed there’s a weird tendency to center yourself as both someone who that could never happen to and someone who is constantly in danger. When really my life has not been touched by the vagaries of the criminal justice system in the same way many other people’s lives have been. It’s not just luck that these things haven’t happened to me. It’s a tremendous amount of privilege.

Absolutely. I’m 41, so that means I was a child in the ‘80s, and the ‘80s was a time when there was this idea of, “Don’t talk to strangers, terrible things may happen.” The Satanic Panic was going on, and there was this real disproportionate idea that terrible things can happen to young, impressionable white children. What is the damage that has been done from that idea? We still need to unpack what that actually means. There’s just so much more work that needs to be done on that scale, in terms of undoing it.

I was thinking of one of the more recent series of CBC’s Uncovered, which I generally like a lot. There was one season on Martinsville, and the Satanic Panic that happened there. Even now, it seems like they’re not really quite sure what happened, not fully cognizant of this series of terrible procedural mistakes and the warping of this idea that you always have to believe the children. We’re still dealing with this conflict between wanting to indulge in believing in extreme behaviour, which I think leads to conspiracy thinking, versus just the everyday horror of what can happen inside a home. That also goes to things like intimate partner violence and violence within communities; somehow they’re just not deemed “worthy” enough for big true-crime storytelling. Or, one of my own pet peeves, which is just revisiting the same famous cases over and over again. I don’t need the 25th version of Ted Bundy unless it’s telling me something absolutely new and fresh. Can we find a new case, or a different case, that tells me something I don’t know?

I think one of the reasons I gravitated a lot towards mid-20th century and more historical stuff was so I didn’t necessarily have to deal head-on with a lot of these things. I could just be like, “I’m dealing with history, so that’s a way for me to think about bigger pictures and try to retroactively apply them to now.” But at the same time, in doing that, it’s like, well, if I’m avoiding the present, what am I actually avoiding here? I think that’s worth interrogating for any journalist, but certainly for me.

You’re working on a book now. Do you find that those questions are informing the work that you’re doing currently?

I’ll definitely be taking that into account. The story is about the time when William F. Buckley, who founded the National Review and was an architect of the neoconservative movement, helped get this man named Edgar Smith off death row in New Jersey for the murder of a fifteen-year-old girl in the late 1950s. [The book] is about an instance where a major public figure believed in the innocence of a man on death row, and that led to real catastrophic results, because of flawed thinking. What does that do, and who gets damaged as a result? Who got lost? I’m hoping once the book is done and ready for publication, a lot of these questions will be fully explored.

It definitely made me see the criminal justice system a little bit differently. I already was, I think, primed to do that, but I think it made me a little more radical about the mistakes that have happened in the pursuit of criminal justice, and how those mistakes keep getting made over and over.

That reminds me of Leora Smith’s piece in the anthology [“How a Dubious Forensic Science Spread,” about the history of blood spatter analysis], which absolutely blew my mind. It was such a specific story but also it felt so applicable to so much of what we’ve all been thinking about the criminal justice system lately. It’s so easy to manipulate these systems, but it’s so much harder to unravel and undo the damage that can be done once someone has figured out how to do that.

I have a master’s in forensic science, so I’m especially interested in stories about junk science. Forensic science is and should be a scientific discipline, with all of the usual built-in checkpoints that scientific inquiry has. But the problem is that in the courtroom, accepting a technique as valid, it has to go through various hearings, and they’re not necessarily done by people who have a lot of scientific expertise, so it can be really gamed. That’s how junk science can get entrenched. But it’s also about magical thinking. I think a lot about lie detector tests. You can never get that through a courtroom, and yet government organizations like the FBI and the CIA still rely on them for interviewing employees. It’s ridiculous to me! This is not a technique that should ever be anywhere, and yet people are still believing that it has some value. It’s like chasing a white whale. Like, “Well, maybe we can find the lie-detector test that is scientifically accurate.” You might as well be a psychic.

But ultimately, the techniques aren’t the issue, it’s human interpretation. Humans get involved in anything, it can lead to mistakes, it can lead to biases, it can lead to all sorts of problems. I think that’s what Leora’s piece brilliantly illustrates. Forensic science is in the middle of its own reckoning, and I think that’s going to continue.

That binge-able idea of a straight narrative with a beginning and a middle and an end where there’s a good person and a bad person... that’s the sort of magical thinking you’re talking about. It’s embedded in the ways so many crimes are actually treated and prosecuted.

Humans crave narrative, and that’s absolutely true in the criminal justice system. We have an adversarial system, it’s, “Whose story is better, whose story is more believable, who is more credible?” And that creates a lot of problems, especially when the wrong person is deemed “credible.” If we can get away from that and accept the nonlinearity of what actually happens with crimes, especially violent ones, and construct narratives that better reflect that, we are ultimately going to be better off.