I was once asked to write an essay that would answer a question: why do so many women writers hate themselves? Self-loathing, they called it, and she was the self-loathing women writer.

I did not like this question, but I did recognize it. I could have given a simple answer in a straight line, cataloguing the many instances of women who wrote about their selves and their hate, and said that this approximated self-loathing. I could have written about women who write about mutually masochistic affairs with people they don’t love or can’t trust, or the posthumous collections of women who lived sad lives and died sad deaths, or I could have written about novels or poems or memoirs about addiction, depression, abusive childhoods, recollections of grief. I could have looked at honest admissions of guilt or regret or sadness or anger and used those emotions to say there, I found her, there’s the woman who hates herself.

But did those women hate themselves, or did they write about their relationship to a world that hated them? Wasn’t self-loathing the symptom, rather than the condition? And anyway, why did we have to consider it in terms of a diagnosis? I thought the inquiry was a statement trying on a question for size, and said as much. I went looking for an answer that would improve the question, which either did not exist or I was not able to find.

Couldn’t it be true that the question was incomplete? Weren’t there other questions—not necessarily better, just other—that could or should be asked before we decided that this determination was our question? The essay went nowhere, but I sometimes think about that woman writer who hates herself, in case she’s still out there, waiting to be found.

*

In 1971, Linda Nochlin published her canonical essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Also a bad question, she argued, one that baited and switched by redirecting our attention to the tip of an iceberg, so we wouldn’t consider its depths. The world as it existed, this question suggested, was good and right, and that women had not succeeded in it must be a mystery for them to solve. “[L]ike so many other so-called questions involved in the feminist ‘controversy,’” she wrote, “it falsifies the nature of the issue at the same time that it insidiously supplies its own answer: “There are no great women artists because women are incapable of greatness.’”

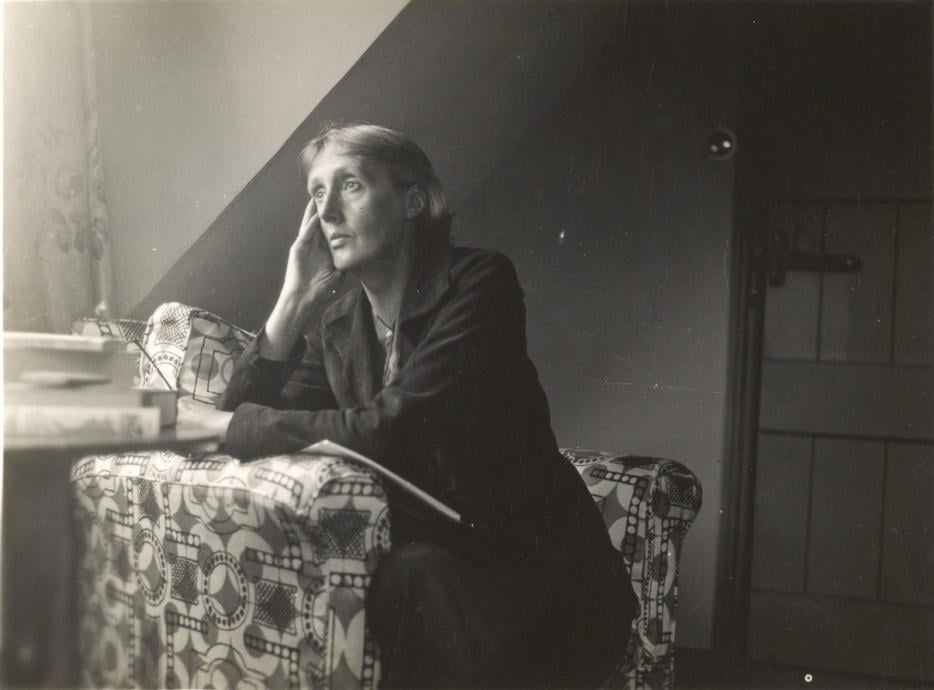

The canon of art history as it stood then (and now) was almost exclusively white, male, and Western, or similar designations we use when talking about people who have personal and professional power over others. And so the standards of greatness were ones that, by design, excluded anyone not of those categories. Meanwhile, the conditions necessary to make art—as Virginia Woolf wrote in 1929, the rooms of their own and the five hundred pounds a year—were not available to women, again by design. Men made women into wives because they needed their labour. Wives were the proofreaders, editors, cooks, babysitters, the names thanked in the acknowledgements of their husband’s books. If they were lucky they got to be muses, forever lying down on canvas. This is the foundation of culture, and also, of everything else: a subjugation based on definitions of gender, race, and class, so that one kind of man can succeed.

“Women,” whatever that means as an identifier or category, is not enough of a link between all the people who could be labelled as such. As Nochlin wrote, when considering the work of Artemesia Gentileschi, Mme. Vigée-Lebrun, Georgia O’Keefe, Helen Frankenthaler, Sappho, Jane Austen, Emily Brontë, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Susan Sontag, just to name a few of her examples, they “would seem to be closer to other artists and writers of their own period and outlook than they are to each other.” Similarities of subjugation are no substitute for solidarity; comparisons have a way of enforcing hierarchies. Still, somehow, we are asked to think of women as a unit, and whatever greatness they achieve is made the proof of an artistic equation.

To consider yourself part of this canon has the effect of a constant psychic flinch. At what price acceptance; at what point will we find ourselves and our work denied or rejected, we wonder. But women have made art, and they still do, tracing the boundaries between their realities and their emotional interiors, their relationship to their world and the way they experience their world relating to them; the question is not where it is, but how it is rated, if it rates at all.

So if the question is the bait, the hook is the thinking which flatters what we believe we already know. “The problem lies not so much with some feminists’ concept of what femininity is, but rather with their misconception—shared with the public at large—of what art is: with the naive idea that art is the direct, personal expression of individual emotional experiences, a translation of personal life into visual terms. Art is almost never that, great art never is,” Nochlin says, and more than that, she concludes, “the total situation of art making…are integral elements of this social structure, and are mediated and determined by specific and definable social institutions, be they art academies, systems of patronage, mythologies of the divine creator, artist as he-man or social outcast.”

But if we are to agree that great art is never personal—and if that I like for its certainty, but hesitate to accept completely—what are we to make of the art that is so clearly the result of an artist’s relationship to their world? Think of how readily we accept what a women writer is, or should be. Think of how often we accept that women write memoir, while men write fact; that women are best at looking inward or to their immediate surroundings—the domestic—while men, accessing some kind of prized fugue state that lets them see with complete accuracy the hearts and minds of every person, everywhere, are given the title of truth-teller and sooth-sayer all at once. Women feel, men report. They guide us, as a culture, forward, and we are glad to follow.

*

There are only two places where I easily and freely give my attention: when I’m reading a book, or watching a movie. I am always studying pages and screens for instructions as much as for the story. And so I’m still watching and reading as so many familiar stories are being told—not new, but now verified by reporters and their institutions. The articles on Harvey Weinstein proved the way he used sex as a weapon, using it to control women’s access, status, wealth, all in comparison to his own. He spent so long living inside the mythology he made for himself, the one where he was a great defender of art, a champion of filmmakers and benefactor of cinema; actresses were required to thank him in their acceptance speeches for Academy Awards, so his name would forever be linked to whatever success they achieved. The reporting on the network of lawyers and investigators that he used to elude consequences show it for what it was: a conspiracy designed to protect his power. So many men are now being seen for what they did; so many of them always, in their own way, make art about their understanding of and relationship to the world. It is not that we know more about their work now. It is that now we must understand their work differently.

Reading the first New York Times article on Harvey Weinstein, I remembered that almost exactly a year earlier I had been observing a conversation between a group of people. They were ecstatic over the release of the Access Hollywood tapes, when Donald Trump bragged about—well, you remember. He was never going to win, they said, but now he was definitely going to lose. No one would vote for him after hearing this, they said to and over each other. I was scared for many reasons then, but the most conscious fear at that moment was: how could we know the same thing and understand it so differently?

After the election, I observed another conversation. They were devastated. Crushed. Their shock was just that, the surprise of realizing they would have to change their understandings of the world, which they did not want to do, not yet, not like this. And I thought: controlled innocence is no different from cynicism. They’re both calculations that allow you to believe you have already learnt everything you will ever know.

And so now that we can’t say we didn’t know, the question has become: what do we do with these men and their art, now that we understand something about them that we didn’t before? What should become of their work? Do we watch the movies, buy the books, see the show? What if, these conversations ask, we don’t, and then we lose something we have all always considered to be of great value? That it is disingenuous to compare the dangers of being wrong with the threat of being right is not considered. The frequently invoked slippery slope is the threat of losing a flattened morality, as though the purest line of vision is one that looks to an agreed-upon horizon; as though hills and valleys of thought are too dangerous to contemplate. I am wondering: when did we decide what everything and everyone was worth?

I guess I spent a lot of time last year thinking about the unasked questions, and if the ones being asked could have better answers. And I still believe in the idea of a pattern or a trend that could be examined, or better yet, understood—as though knowing has ever been the same thing as understanding.

The question of what to do with the art of abusers takes much for granted: first, that the art matters most, and second, that out of all kinds of artists, men deserve to be saved. We have determined their worth before we set the terms of value. Staring too closely at these questions has made me feel like I am looking at something that shouldn’t be examined from such a perspective. And anyway, thinking too much about patterns is what happens right before thinking too much about conspiracies, and then you’re the woman wearing the tinfoil hat, yelling about the connections that only you can see.

*

In 1965, Harpers published an edited transcribed version of a talk given by Tillie Olsen, which she called “Silences in Literature.” Olsen was looking for what she considered hidden or unnatural silences—not the necessary fallow periods where writing has to be dormant so ideas can form, these are the silences of “creative suicides,” from censorship to perfectionism, an absence of time or support or other material conditions necessary to write. “We must not speak of women writers in our century (as we cannot speak of woman in any area of recognized human achievement),” she wrote, “without speaking also of the invisible, the as-innately-capable: the born to the wrong circumstances—diminished, excluded, foundered, silenced.”

This is an impossible catalogue, as it is only an archive of loss. The question has been asked for centuries: who are we missing? How could we know. In 1883, Olive Schreiner wrote From Man to Man, asking how many Shakespeares we had been denied because they were born the wrong race or class or gender. “What statesman, what leaders, what creative intelligence have been lost to humanity because there has been no free trade in the powers and gifts.”

When Woolf gave her speech, asking, too, what if Shakespeare had been born a woman, she also offered an answer as to where to find the missing, a better version of the cliché that behind every great man is a great woman. When “one reads of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even a remarkable man who had a remarkable mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, or some Emily Brontë who dashed her brains out on the moor, crazed with the torture her gift had put her to.” Is it time to add to this list: if we are looking for a lost artist, look for the men who hated women. Look for the men we always knew, but refused to understand.

Then: what do men say about the women who disappeared, if they consider them at all? She was crazy? There’s the tinfoil hat again. And the women who did make art, who tried to tell the truth about what had happened to them—well, maybe they hated themselves?

When I was looking for the self-loathing woman writer, I thought it was necessary to separate the emotion from the experience: that while I knew there were many instances of women hating themselves, I believed that was different from being a self-hating women. If women make art about their relationship to the world—not the same as making art about themselves, but not wholly distinct, either—why would they not reflect a life lived in a world that hated them? I read Simone Weil, who, in Gravity and Grace, called this destructive drive for balance “analogous desires.” “It is impossible to forgive whoever has done us harm if the harm has lowered us,” she wrote. “We have to think that it has not lowered us, but has revealed our true level.” At thirty-four, Weil died of anorexia-induced heart failure. Her biographer, Richard Rees, said she died of love. “I should not love my suffering because it is useful,” she wrote, not willing to be the self-loathing woman writer. “I should love it because it is.”

When Toni Morrison published The Bluest Eye in 1970, she was explicitly trying to write about the analogous effects self-loathing creates for families, communities, and in history. In the foreword for the 2007 edition, Morrison said that she is sure everyone knows what it feels like to be disliked or rejected or hated, “for things we have no control over and cannot change.” But she explains that this hatred comes with its own kind of grace: believing you deserve better. The Bluest Eye, she writes, was about the people who learn to hate themselves, “the far more tragic and disabling consequences of accepting rejection as legitimate, as self-evident,” and became either much worse for it or “collapse, silently, anonymously, with no voice to express or acknowledge it.”

Morrison had a friend in childhood who wanted blue eyes, like Eye’s Pecola Breedlove, the little girl who internalizes the hatred she experiences so intensely she prays to God that she might disappear. “Implicit in her desire was racial self-loathing,” Morrison says of her friend. “And twenty years later I was still wondering about how one learns that. Who told her?” Morrison asks us who told her friend to hate herself only to force us to consider who hadn’t told her friend that she should hate herself as much as the world hated her, if not more so. Who had, worse yet, told her she should love her suffering?

The “Sylvia Plath Effect” is the theory that poets are more likely to suffer from mental illness than other kinds of writers: Plath’s name is used to diagnose other women who look like her. In Negroland, Margo Jefferson’s 2015 memoir, Jefferson wrote about Anne Sexton, who some say suffered from her own version of the Sylvia Plath Effect. “I’d always derided Anne Sexton’s suicide competitions with Sylvia Plath,” Jefferson says. She quotes Sexton’s writing: “Thief! How did you crawl into/crawl down alone/into the death I wanted so badly and for so long?” In response, Jefferson says “Maybe because Plath had more nerve and wrote better poetry.”

In her reminiscences, Jefferson writes of learning, over the course of her childhood, to recognize how and why she should hate herself. “I hated being caught unawares. It was so dangerous, so shameful not to know what I needed to know,” Jefferson tells us, explaining how she turned those external instances of loathing into herself. “There are so many ways to be ambushed by insult and humiliation.” But Jefferson could not, she writes, qualify as suffering from the Sylvia Plath Effect. As a black woman, she was “denied the privilege of freely yielding to depression, of flaunting neurosis as a mark of social and psychic complexity. A privilege that was glorified in the literature of white female suffering and resistance.” In time, Jefferson grew to consider her self-loathing reason enough to die, and her anger at this learned response is carefully measured. “My people’s enemies have done this to me. But so have my own loved ones…Let me say with care that the blame is not symmetrical: my enemies forced my loved ones to ask too much of me.”

The suggestion to learn to love your own suffering, as a way of achieving goodness or grace, was perhaps the best example of self-loathing I found. It is a literary convention that is also a boundary, drawing the woman deeper inside herself and denying the relationship between the artist and the world she lives in: if she doesn’t hate herself yet, maybe she should start. By stopping at the surface of what the art is, rather than asking what it does, or who the art is for, we avoid asking a question that might cost too much: who hates? What does that hate do? In “Silences,” Olsen says women have a responsibility to say what it is they hate, rather than turning it inwards. “Be critical. Women have the right to say: this is surface, this falsifies reality, this degrades.” Women also have the right to say: I’m not silent. I’m thinking.

*

I did find, in my readings, that some women writers share an openness and an acceptance of hatred. It is a style of protagonist seen recently in the very popular short story published by The New Yorker, “Cat Person,” which had the contours of an amorphous but present trend in contemporary literature. Readers can find it in the novels and short stories of women like Otessa Moshfegh, Danzy Senna, Natasha Stagg, Myriam Gurba, all of whom have very different styles and different ideas, but retain a similar perspective: a narrator with an internal monologue so minutely aware of their external environments that every thought and every observation takes on a quality of the perversely absurd. The sex they have with other people is frequently motivated more by momentum than desire; the work they do is negligible or undervalued. They do not hate themselves, but they are aware that they might be hated, and this is distressing but also a little silly, and sometimes funny. Previous generations of readers had Jean Rhys, Fanny Howe, and Mary Gaitskill, to name just a few; in the past year, Margaret Atwood’s narrators and style have moved from books to prestige television, with her unnervingly cathartic depictions of worlds realer than the one we were living in, or maybe a world that was more truthful: the motivations and machinations of men in power had been laid bare in the country she called Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale, a dictatorship in which women are reduced to their bodies and their service, so that readers and watchers could consider what it would be like if those feelings we knew men had were no longer kept in code. Maybe that’s why some women dressed like handmaids at marches or for costume parties—I found the visuals much worse than the imaginings, so I couldn’t understand the appeal. The shock for me was felt the hardest when I read Atwood’s explanation for how she wrote the story: her only rule was that she could only include what had already happened in the past—the many historical references for women losing the rights they had barely ever had—making it not the future but our past and present.

Meanwhile Alias Grace, the latest of her books to be adapted into a straight-to-streaming television show, is Canadian prestige of the highest order: written by Sarah Polley, directed by Mary Harron, and starring Sarah Gadon, the show and book inspired by the true story of Grace Marks, a woman convicted of murdering her employers in 19th century Toronto. They work well together: one composed of real situations experienced by a fictional woman, the other a real woman made into fiction as the best way to understand her mind. They are both written as letters, in their own way. Tale ends with a funny coda, saying that it was all a diary written by Offred and found, now, as an artifact to be studied by a presumably more stable society in the future. Alias Grace is mostly epistolary, formatted by the ongoing first-person account Grace Marks is giving to her new doctor, about the circumstances that led to the murder charge. Both characters want a record. More than that, both characters want a reader. Olsen said that to not have an audience is a kind of death. To characters who believe their death is not just certain but imminent, they write for another kind of mortality. They have learnt something they need us to know.

Olsen quotes Whitman in "Silences" when she says that women are “hungry for equals.” She talks about the 1974 National Book Awards, when Audre Lorde, Adrianne Rich, and Alice Walker were placed in competition as nominees against each other. Rich won the poetry award and “refused the terms of patriarchal competition,” insisting on accepting the award on behalf of women, who deserve better than the assumption they will be grateful to be included at all. In a joint statement between all three, they wrote that they “accept this award in the name of all the woman whose voices have gone and still go unheard in this patriarchal world, and in the name of those who, like us, have been tolerated as the token women in this culture, often at great cost and in great pain…We dedicate this occasion to the struggle for self-determination of all woman, of every color, identification or deprived class…the woman who will understand what we are doing here and those who will not understand yet: the silent women whose voices have been denied us, the articulate women who have given us strength to do our work.”

*

In the last year, I’ve watched so many people tell a truth they thought they knew, but now the reality seems different. We kept the memories to ourselves for so long that now when we need them it feels like remembering a dream. The cab he insisted we take; his hands around our wrists, which he removed, after we pulled away. Fights about his friend—why even invite him to the bar, when we know what he’ll do? The editor who asked if we were single, because stories about wealthy men who fucked did well for his publication. The editor who wanted us to know his marriage was over, really, he and his wife didn’t have to talk about it, they both knew. A filmmaker once told me he wrote a rape scene because he wanted to show the truth about what happens to women; the truth about power. Who needs to be shown that truth, I asked him. What audience is this for? The women in the audience will know what rape looks like, what power does. We’ve kept archives — not just memories, but the emails and texts — even if we never claimed them as our own, of men and their words. Still, we thought it was us, and that what happened could be true but must not be real. We were the ones still looking for better questions, and men were already answered.

Men, it seems, believed in their own greatness, and would go to great lengths to keep it. In her essay for n+1, Dayna Tortorici asks if history must always have losers, and whether men are prepared to see a new understanding as anything but a loss. “The way they had learned to live in the world — to write novels, to make art, to teach, to argue about ideas, to conduct themselves in sexual and romantic relationships—no longer fit the time in which they were living. ...Their novels, art, teaching methods, ideas, and relationship paradigms were all being condemned as unenlightened or violent,” she writes. “Authors and artists whose work was celebrated as ‘thoughtful’ or ‘political’ not eight years ago were now being singled out as chauvinists and bigots. One might expect this in old age, but to be cast out as a political dinosaur by 52, by 40, by 36? They hadn’t even peaked! And with the political right—the actual right—getting away with murder, theft, and exploitation worldwide . . . ? That, at least, was how I gathered they felt. Sometimes I thought they were right. Sometimes I thought they needed to grow up.”

For a long time, I studied the ways I thought I could be a woman more than I ever studied anything that could be considered a more practical education. I was relieved when I realized that there was so much literature on how to be a woman—which, to me, meant: how to make a man want you—and that if I followed the advice of magazines I could approximate the way a woman should look. I could read books and watch movies as though they were instruction manuals, which, if you think about it, they were. I recognized the guidelines for etiquette hidden in morality or fairy tales, and was grateful for their messages, even if I frequently missed the point or didn’t care to notice the contradictions. I would make myself uninterested like Anne with Gilbert, or Jo with Laurie, so that my affection would be a better prize; hold fast to my virtue like Jane Eyre, so that my eventual acquiescence was more deserved. I was much too old by the time it occurred to me that Mr. de Winter’s version of events was not to be trusted. I forced myself to read Anna Karenina at age ten, wanting to appear precocious, and flipped through everything that had to do with landowners and feudal systems, because she had a husband and a lover, so she really knew what she was doing. I thought deeply about what kind of Babysitter’s Club member I would be. At the movies, I considered: should I be more like Gaby Hoffman or Kirsten Dunst?

Sometimes I worried that I would have never been able to figure out how to be a man as easily. It seemed like there was no parallel for them: Where were their magazines telling them how to look and dress? What books were they reading? What movies explained to them how to make someone love you, or at least want you for a time? It didn’t occur to me that they were less in need of instructions, living in a world made by fathers and mentors so that their paths would always be cleared, and it certainly did not occur to me to think about who decided which movies got made and which books got published. I fell in love with the virtues of reading before I understood what I was teaching myself to learn, which was: how to be wanted and how to be hated, for the same reasons. Isn’t that how it always happens? The moment when what you love comes before you know why you love; or even before you know if it’s worth loving at all. And then we work so hard to hold on to that first thought, as though it is our best thought, knowing and feeling not opposed but no matter how hard we try to make it so it is not the same.

In her essay about the relationship between Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger, Vivian Gornick says their love belongs to “the dramatists, not the critics. It is a tale of emotional connection made early, never fully grasped, then buried alive in feeling the protagonists kept hidden from themselves.…interesting, as the dramatists know, only when presented inside a larger mythology, one that provides an objective correlative to the uncontrollable need of the protagonist.”

Arendt was eighteen when she became Heidegger’s student, still eighteen when they became lovers, and she spent her whole life (and his) knowing that love better than she would allow herself to know him. Even after their affair ended she refused to reject him: even after he publicly endorsed National Socialism in 1933, and even after he lived through the war as a Nazi, she always considered him a “political innocent.” They reconciled in 1950, corresponding and meeting periodically until they died, her in December 1975 and him in May 1976.

Gornick believes Arendt lived worshiping what she thought was Heidegger’s “transcendent mind,” a bond that had been eroticized in their affair and consequently fused into her being. The conflation of sex with understanding can ruin the best of us. “The impulse to rationalize its ‘contradictions’ replaces the impulse to act rationally, and looks,” Gornick reminds us, “to the one doing it, like the same thing.”

What is the moral of this story? A bad question. What feels true about this story? It is the way we learn before we know. It is “the history of shared sensibility, the thing we all felt up until yesterday,” Gornick says. “How many women and men have I, in my short, obscure lifetime, watched subjugate themselves to The Great Man, the one who seemed to embody art with a capital A or revolution with a capital R? Our numbers are legion. We ourselves are intelligent, educated, talented, none of us moral monsters, just ordinary people hungry to live life at a symbolic level. At the time, The Great Man seemed not only a good idea but a necessary one, irreplaceable and unforgettable."

Sometimes we’re asked to consider that no one really knows what happens between two people when one or both thinks that no one is looking. Most of us learned very young that even our perceptions are not to be trusted. And so we don’t consider the question of “he said/she said,” the way we’re sometimes presumed to, as being a struggle for accuracy. It is the way we work to explain whose words we trust to describe it. Spend enough time in a conversation where no one believes what you say, and all your words feel like fiction.

These understandings are all so old. They are only new in relation to who is willing to know them, now. Art has the same barriers to knowledge that people have, which is that we frequently are pressed up against the limits of our own understanding, and that we are trying to make do with what we have, which is: not enough. The questions we choose to ask and answer are important. What are the material conditions necessary for a woman to make art, we wonder. What would art be if the canon no longer depended on the myth of the great man, or if the great man no longer centered our standard for greatness. What would our relationships be to ourselves, and to other people like us? Who have we lost by searching for ghosts? No longer the woman writer who hates herself, or the missing woman lucky to be found at all—who would we find if we knew who we were looking for? I have searched too closely and for too long in the work that already exists, as though it will supply the good answer. So many of my nights end with me, in bed, staring at another screen, asking myself another question, and I think: I should really be reading a book.