Washington, D.C., is a time warp, a place with so much history it’s almost inevitable that the present will occur in uncanny proximity to the relics of the past. For example, I’m in a bagel shop on U Street, a couple blocks from the Mary Ann Shadd House. The residence is listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Shadd was the first African-American woman to publish a newspaper, and would later go on to become one of the first African-American women to practice law. Later this afternoon, six journalists will be arrested for covering an anti-racist, anti-fascist demonstration that gets out of hand. In five days, they will be charged with felonies.

“I can’t believe this is happening,” says an African-American woman in line behind me. The rest of us, employees and customers, all shake our heads or make faces or sigh, trying to let her know that none of us can either. I pulled an accidental all-nighter, wracked by both insomnia and the nagging hope that by staying awake I could stave off Donald Trump’s presidency for as long as possible. It worked, I guess, in that I got a few hours of the Obama administration that most people forfeited. But it’s morning now, and it’s happening, and I feel like shit. Then again, I was probably going to feel like shit anyway.

Pressed for time, I hail an Uber. “Yo man, you gotta see this,” the driver tells me when I hop in the backseat, brandishing his phone. I want to get moving, so I ask if I can check it on the way, but there’s not much of a way to be on, he says. “Police is gonna be crazy down there now. Check it.” He pulls up a video of someone smashing out the window out of a black SUV with the Trump Organization logo on it, parked maybe two-hundred feet from the bagel place. Though you can barely see what’s going on in the frame, the driver narrates the action in urgent Spanish. Police sirens blare both from within the phone and without. At some point in the video the driver flips the perspective on the camera, giving the viewer a “holy fuck I can’t believe that just happened in front of me!” expression. As we get moving, a team of bike cops, cheerily oblivious to the fucked-up car, ride past us, smiling and pumping their fists. “He’s the president now,” the driver tells me. “I don’t know what we’re gonna do.” He takes me down to the police barricades on K Street, and I start walking.

The Trump voters carry themselves like they’re headed to a Super Bowl they’ve already won, smiling and drinking and marvelling that this city isn’t anything like wherever they came from, occasionally scowling at someone who isn’t a white person wearing a Make America Great Again hat. Around them, protesters carry signs and jeer and are as vocal as possible the fact that This Is Not Okay. Someone in a Vladimir Putin mask leads around someone in a latex Donald Trump head and a sex-store dog collar. A group of women walk around holding a banner that reads, “What will we do today to dismantle white supremacy?” A man weaves through the crowd, blasting YG’s “Fuck Donald Trump” on a Bluetooth speaker.

“Those guys need to get over it,” says a guy in a MAGA cap as he passes a group of protesters on F Street. I start to tail him, hoping he’ll lead me to Trump’s swearing-in, but after half a block or so I realize there are just as many Trump supporters walking in the opposite direction.

In a sense, presidential inaugurations are plays in which each attendee has a role. The well-wishers and protesters are dueling Greek choruses performing for the media, there to tell the rest of the world what it already knows, that some people are happy about Donald Trump and other people are not happy about Donald Trump. Reporters, photographers, camera crews, and a guy in a suit wearing an official-looking lanyard that just says “comedian” scurry about, trying to document the rudest Trump supporters, the most outrageous protesters, the tensest moments between Trump supporters and protesters, protesters and the cops.

Then there are the street vendors selling bootleg Trump merchandise. They’ve got seemingly every Make America Great Again hat permutation: fitted caps, trucker hats, and baseball caps, with backs that snap, strap, or Velcro, whose brims are either flat or curved, some with that some string where the bill meets the crown, others with Donald Trump’s signature embroidered on them. (Later, in a souvenir shop, I will also find a Make America Great Again bucket hat.) Many sell T-shirts with a large presidential seal printed on the chest, with Donald Trump’s picture where the eagle should be. Some sell leftover stock at discounted prices: buttons that say “HILLARY FOR PRISON,” white beanies with the word “OBAMA” stitched on them.

A couple blocks from the mall, I stop to consider a T-shirt featuring Donald Trump as a Minion, accompanied by the text, “DEPLORABLE N’ CHIEF.” As I stand there dumbfounded, everybody in a nearby bar starts cheering. It’s starting.

Covering rap is weirdly good preparation for covering politics—finding a last-second comment for a story about an emergency session of the North Carolina legislature is a cakewalk compared to navigating the thicket of publicists, managers, and personal assistants trying to keep you from getting Rick Ross on the phone.

Once inside, I find the place, like the rest of the neighborhood, is packed with Trump supporters. Well over half the people are wearing the Red Cap of Oppression. They are overwhelmingly white, many of them preppy, and mostly kind of drunk. When Trump starts taking the Oath of Office, the volume and aggression of the crowd combine to make me feel physically sick. The only other person around me who doesn’t seem tickled pink with bloodlust is a woman standing next to me who says “nooooo!” under her breath. The next table over, a pair of guys with face tattoos are drinking Bloody Marys and splitting an order of fries, seemingly oblivious to the scene around them.

Shortly after Barack Obama officially becomes an ex-president, a middle-aged man wearing a T-shirt that reads “The Constitution: I read it for the articles” screams, “GOODBYE TO THE TRAITOR!” Nobody in the bar joins in, but they don’t do anything to suggest he shouldn’t have done it, either. The guys with face tattoos use the momentary lull in the action to wave over a waitress and order a couple beers.

Whenever Trump hits a particularly scary line in his inaugural address, everybody in the bar goes bananas. Now that he is president [cheers], Trump explains, the American people are in charge [cheers]. It’s the “hour of action,” which means it’s time to build roads [cheers], go to space [cheers], and ensure “radical Islamic terrorism is eradicated from the face of the earth” [lots of cheers, guy in the constitution T-shirt yells something racist]. Oh, and if any of the stupid dumb hater countries and stupid dumb loser countries don’t like it, then they can pay a visit to the ol’ shit buffet,11I’m paraphrasing here. because we’ve got the Army, police, and God on our side [loudest cheers so far; the racist guy grunts racistly]. It goes unspoken but understood, among the Red Hat People, that if you disagree with Donald Trump that means you disagree with America, and if you disagree with America then not even God can save you. As he wraps up the speech pledging, as always, to “make America great again,” the entire bar chants along, as if Trump were a priest leading them in prayer.

When Trump’s address reaches its merciful conclusion, I meet up with my photographer to check on the protesters who had been blockading several of the security checkpoints, causing long lines and doing their part to deprive Trump of the huge inaugural crowd he clearly craves. They’ve mostly dispersed, except for a group on 10th Street who enthusiastically chant, “Go another way!” at a trio of bros in MAGA hats, who after some light heckling do indeed turn around. Up the street, I catch them taking a selfie. “Do you guys smell weed?” one of them asks. “Fuuuuuuuuuck yes dude, we gotta find some weed,” responds another.22Someone was, indeed, smoking weed.

On New York Avenue, a thousands-strong parade of demonstrators clogs the streets, holding signs and chanting. I hear the rumble of skateboard wheels and turn to make sure I’m not in someone’s way, and when I turn back around, a man is walking past me inexplicably leading four llamas. A group of pudgy white guys with stringy hair approaches, stopping to scream, “Hail Trump!” Just as they’re about to walk past, disheartened by the lack of response, one of them stops his friends. “DUDE—llamas!”

As I head away from the protests to catch an Uber, I find a cop talking to a bootlegger—not to give the vendor shit but to buy a Trump T-shirt. Up the street, a guy with a red hat leans into the open window of a police car. His ass sways gently; he puts his weight on the vehicle like he would collapse if it weren’t there. “Man, sir,” he tells the officer inside, “I fuckin’... appreciate your service.”

*

When people ask me what I write about I tell them politics, which is true enough not to be a lie, and that I used to write about hip-hop, which is true enough to be true without any qualifiers. It turns out covering rap was weirdly good preparation for making the switch—if nothing else, finding somebody to offer a last-second comment for a story about an emergency session of the North Carolina legislature is a cakewalk compared to navigating the thicket of publicists, managers, and personal assistants trying to keep you from getting Rick Ross on the phone. On a deeper level, both mainstream hip-hop and national politics occupy the liminal space between the out-and-out pageantry of pro wrestling and the cold frankness of true reality, where things said and done for show are saddled with the burden of existing in a multiplicity of contexts. The difference, of course, is that hip-hop reflects, while politics projects. Rap lyrics intended to explain the mindset of a gang member might be interpreted by the square community as glorifying the gang lifestyle. Or a song understood by hip-hop fans to be hyperbolic aggrandizing, no different in tone from a Fast and Furious movie, might be taken by Bill O'Reilly types as pure documentary. In politics, meanwhile, anti-immigrant comments meant to rile up your base might lead to an uptick in bullying at schools. You pass legislation to keep assault weapo ns available in gun shops as a bone to the NRA people, and somebody might buy one and go kill somebody with it.

The shift to politics is recent. Last July, I moved across the country back home to a small town in western North Carolina to work for my dad. He’d offered me a job once before, right before I graduated college, a last-ditch effort to get me to join the family business. This time, he’d sold the family business to run for the House of Representatives. “Not the state house,” I’d tell my friends back in Los Angeles. “The regular one. Like, the American one.” I had no idea what I was doing, but then again, neither did he.

Of all the states in the nation, it is perhaps hardest for a Democratic challenger to win a congressional seat in North Carolina. In forty-two states, congressional districts are drawn by the state legislature every time they release a new census, meaning that whichever political party controls their state’s legislature during a census year gets to draw their national congressional districts whichever way they please. During the 2010 midterms, the Republican Party seized upon this quirk of the American political system, ferreting hundreds of thousands of dollars in dark money to state legislature candidates throughout the nation, picking up almost seven-hundred seats and all but guaranteeing a Republican majority in Congress when it came time to redraw the districts in 2012. North Carolina’s thirteen congressional districts were hit particularly hard by this effort, and the number of reliably Democratic districts dropped from seven to three. My dad, a progressive Democrat whose favorite presidential candidate was Bernie Sanders, was not running in one of those districts. And when, early in his campaign, our state’s congressional districts were ruled unconstitutional and the legislature was ordered to redraw them, they somehow managed to make the district even more conservative.

As we compared our district’s number of registered Democrats (low) with its number of registered Republicans (high), my dad and I jokingly developed what we called “the angry nerd” theory of politics. The idea was that under normal circumstances, people are barely cognizant of local political races33Given that they tend to span only a few counties, Congressional races are often considered “local” despite being races for national office. and could not care less who their congressman is. If a candidate could identify the people in their district who were predisposed to agree with what they had to say and then get those people really fired up, they would win regardless of how many Democrats or Republicans—let alone talismanic “undecided voters”—actually lived there.

My dad campaigned tirelessly, at one point literally running from town to town in the district asking people for their support. He raised more money than any other Democratic challenger in the state. Bill Clinton’s former chief of staff recorded a phone call to donors on his behalf. The chair of the state Democratic party threw her weight behind him, and he spoke at events with Roy Cooper, who was eventually elected governor. It turned out my dad had a knack for giving stump speeches, and seemed to win new supporters every time he spoke at an event. On the first day of early voting, he drove from polling place to polling place, strangers cheerfully approaching him to let him know he had their vote. When returns came in, he ended up with more votes in the district than any other Democrat, including Hillary Clinton. It seemed as if our theory had been correct.

There was only one minor snafu—my dad lost. Badly. I love him too much to tell you the exact number, but rest assured it was a landslide we didn’t see coming. Part of this had to do with the power of incumbency, as well as our tendency to focus on what’s in front of us—we’d managed to convince hundreds, if not thousands, of people that my dad would make a great congressman, sure, but we’d momentarily forgotten that despite our best efforts there were still the tens of thousands of people in the district who still had no idea who he was and voted for the other guy simply out of habit. Those factors contributed to my dad’s loss, but the reason my dad got his tuchas handed to him was Donald Trump, who won the state by nearly twice the margin Mitt Romney had in 2012 and was operating under his own version of our “angry nerd” theory. Though it’s by no means the only reason he won,44James Comey, Jill Stein, Gary Johnson, Vladimir Putin, Julian Assange, social media leading to political polarization, racism, sexism, xenophobia, white backlash to a Black president, rising health insurance premiums, and Bill Clinton. Plus Hillary Clinton’s poor campaigning, her extreme secrecy, and her lengthy public record which made her vulnerable to attack. Oh, and her campaign’s bizarre decision not to go to Michigan in the days leading up to the election. Trump managed to essentially frack the electorate in our part of the state, tapping into a reserve of voters who were ostensibly disinterested in politicians and convince them to vote Republican all the way down the ballot.

Perhaps the most frustrating thing about the outcome was that my dad’s opponent seemed to know what was going to happen all along. He spent the run-up to the election barely campaigning, instead flying around the country raising money for Republican candidates whose seats weren’t considered “safe” by dint of demography. Back home he set out a few signs, showed up to the town hall meetings that congressmen are required to hold in their district, and dutifully participated in a pair of debates. The night of the election, my dad called him to concede. He didn’t pick up, and he never called back.

*

The pageantry of inauguration day, once concentrated around the National Mall, has moved on. To luncheons and galas and balls for the statesmen, tacky bars and overpriced hotel rooms for Trump supporters, the streets and the chaotic moral high ground for demonstrators, and jail cells for the unlucky few who got boxed in by the police.

Like any other theater that’s just let out, the Mall itself is empty but shows evidence of a crowd. The much-touted white plastic ground covers are now muddied, covered in paper cups and napkins and programs with an errant glove or scarf mixed in for good measure. The Capitol Building is illuminated, the ominous American flags still hanging between its columns. The dais where Trump took the Oath of Office is still standing, the Capitol’s lights filling it with a washed-out glow. From where my friend and I stand near the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool, we can see men in jumpsuits sitting onstage, lounging in what look like the chairs in which Trump and Pence sat as they were sworn in. The image is kind of funny at first, but it’s really pretty normal—just some guys sitting in some chairs on a set after the show’s over.

In the days leading up to the inauguration, I read about Donald Trump until I couldn’t. I delved into his cabinet appointees, his conflicts of interest, his cabinet appointees’ conflicts of interest. I brushed up on the emoluments clause, looked at reports detailing his mob connections. I hosannaed when I saw the pee thing on BuzzFeed, and I perked up at the news that a former Apprentice contestant who had accused him of inappropriate sexual conduct was now suing him for defamation. Each day, a bread crumb of hope that the adults would step in and say “Alright Donald, that’s enough, you leave governing to the big boys.” These turned out to be liberal fantasies, of course, deus ex machinas no more likely to materialize than some damning evidence that Barack Obama had, in fact, been born in Kenya. And even if these nuggets of hope had some real bite, Donald Trump and his people are in charge now, and they reserve the right to interpret the rules so that their team doesn’t get punished.

Then again, that’s probably what the people who hated Hillary told themselves every time the right-wing media batted around another story about dead FBI agents or warehouses full of pre-marked ballots or powerful Democrats running a child molestation ring out of a pizza place that throws punk shows. Does it matter that the stories I tell myself are true if they yield the same outcome as the stories that aren’t? In the end, what gave me the most hope was a video of the rapper Waka Flocka wiping his bare ass with a Donald Trump jersey. A futile and childish gesture, sure, but at least he was under no illusions it wasn’t.

We’re hungry, and the only restaurant with the lights still on is a by-the-slice pizza place. A middle-aged couple in formalwear stands at the counter, subtly shifting their balance as they chat with a man sweeping pizza off the counter and into the trash. “We’re closed,” the guy tells me without looking up.

“Pleeeeeease,” says the woman in the gown. “Just let ‘em take some pizza with ‘em real quick.”

“C’mawn,” says the man in the tuxedo. “Y’all did it for us.”

Each speaks with the lilting drawl and rounded tones of southerners who come from money. From having grown up in North Carolina, I can tell you that these sorts of people are incredibly polite and accommodating to whoever is directly in front of them, defaulting to the role of “host” in any given social situation. Sure enough, the man pulls out a twenty from his wallet and slides it across the counter, and the man behind the counter starts pulling slices from his remaining stock and putting them into two boxes. “He does this all the time,” the woman says, beaming.

“We’re from Charleston,” the man tells us. “Our congressman invited us up for the inauguration personally.”

“That’s amazing,” I say, slipping into a southern accent of my own, as I tend to do when talking to old people and/or cops. “Which congressman?”

He says a name neither my friend nor I recognize, leaving the conversation at a momentary impasse. D.C. is flush with out-of-towners who are all here for Donald Trump, and a friendly chat with a middle-aged guy who just bought you pizza can go drastically awry if you make a comment aimed in the wrong direction.

“It was like being in Hollywood,” he says, as if we were playing a friendly board game and I’d simply skipped my turn. “We saw Paul Ryan and Ted Cruz and John McCain, just everybody.” That’s another thing about southerners, regardless of their politics—they refuse to let a conversation die.

This morning, everyone had shown up in uniform: the Trump people had the damn red hats, maybe something with an American flag pattern, while the anti-Trump people wore black or, at least, nothing to suggest they’d been jettisoned from a tornado that had swept through a country club. Formal attire doesn’t let people know how you voted, just that you were somewhere fancy before you got to wherever you are now.

Down the street, more people in tuxedos and gowns trickle into the Capitol Lounge, which is kind of like a divey sports bar but for people whose favorite sport is politics and whose favorite team is the Republican Party. There’s a big inflatable elephant outside, the Don’t Tread on Me snake printed on a lampshade above the bar, and an appropriately bland selection of macrobrews on tap. The walls are covered in layers of kitsch from Republican campaigns of yore, so thick that without them the building might collapse. Rae Sremmurd’s “Black Beatles” is playing on the jukebox; just beyond the bar, a small group of guys sporting frat shags55For those of you who didn’t attend colleges heavy on Greek life, this is the type of hair that happens when preppy dudes have gone several months without a haircut and everything gets all swoopy. of varying severity nod their heads in time with the beat.

There’s no music playing in the bar’s other room—called the “Nixon Room,” because the walls are full of Richard Nixon shit—just a bunch of TVs playing CNN. Right now, the Trumps and the Pences are all dancing with members of the Armed Forces. As the new president sashays with a female soldier, the cameras catch him whispering something into her ear. She smiles, and before we can see if she whispers anything back CNN cuts to a shot of a dashing Marine dancing with a visibly jubilant Karen Pence. Later in the event, Trump uses a sword to cut into a mostly Styrofoam cake whose design was ripped off from a real cake Obama used in 2013.

Much like everything else about Trump, his vision of glitz and glamor is shamelessly chintzy and wilts under close examination, but the “show business” aspect of the presidency—in which the Commander in Chief is the ultimate reality TV star—is undoubtedly why Trump ran for office in the first place. In his mind, the president spends his time attending events in front of camera crews, stoking beefs with rivals both foreign and domestic, smiling and shaking hands and signing things he hasn’t actually read while less telegenic people do the actual work of running the country. It’s easy to see how such a position, if it were to actually exist, could appeal to anybody, especially an egomaniac.

But unlike other masks Trump has cycled through in his life (“mogul,” “pro wrestling heel,” “television personality”), the incomprehensible power and responsibility of the presidency means that those who don it can’t cast it aside when they feel bored or restless or horny. The Republican establishment, it seems, is all too eager to make things as easy for him as they can, let him perform “president” when he pleases, free to bloviate in front of microphones and attend banquets and cut facile deals with manufacturers and tweet about what a fantastic and beautiful job he’s doing while they handle the rest, kissing the ring that projects a smokescreen from behind which they can wreak post-Neoconservative havoc.

If there is a silver lining to Trump, it is that he inspires reactions so strong that the artifice becomes transparent. Earlier in the day, a news report had interrupted real-time footage of the protests in D.C. to show a group of soldiers standing motionless on the steps of the White House, waiting for Trump’s motorcade to arrive. The producers didn’t cut away from the scene, however, instead shifting to a split-screen view as the talking heads seamlessly transitioned from breaking down the process of lighting a garbage can on fire to babbling about how this would be President Trump’s “first chance to salute his troops,” bantering about the saluting techniques of past presidents. All the while, the other frame silently lingered on shots of smashed-out storefronts and disfigured limousines, cutting to protesters fleeing tear gas and concussion grenades. If the talking heads found this juxtaposition stark, they made no note of it.

*

My mom has never done drugs. She has never listened to punk rock. She was born too late for Vietnam; she has never dabbled in Marxism. She’s a rule-follower. Right after she and my dad got married, they called in sick and went and hung out on the river; she got a sunburn and was racked with paranoia at getting caught. A few times in college, she once told me, she smoked cigarettes—but she did NOT inhale. All her life she’s been content to go with the flow, more than happy to make the best of whatever’s in front of her.

But during election season, as she and my dad drove all over tarnation campaigning, Donald Trump was what was in front of her. He was like a disease that had infected everyone and everything around us. When we went to a county fair, she watched a small army of people in “Deplorables” T-shirts scream at passers-by about immigrants. On Halloween, a family in the neighborhood put a scarecrow wearing a T-shirt that said “Hillary for Prison” out by the road, surrounding it with signs with things like “YOU DIRTY RAT” and “PRISON YES, HILLARY CLINTON NO NO NO!” written on them in sharpie. After she discovered it, she stopped walking the dog that way. Every night he was in our home, hollering and leering from inside the TV. By the time the Access Hollywood video came out, she’d instituted a new rule at home: no Trump on TV when she was in the room. This was back when Trump seemed like a passing nuisance, an overgrown Bart Simpson mooning America while riding shotgun in a car headed out of town and into obscurity. Hillary was going to win, things weren’t going to be amazing, but they’d be good enough and that was fine with her.

My mother is a person who makes decisions carefully. She doesn’t like to take risks, but when she sets out to do something, nothing and no one can stand in her way. And when it became overwhelmingly clear that Trump wouldn’t be going anywhere any time soon, she made a decision.

“I’ve never protested anything before,” she told my dad and me over Christmas. “But I’m going to go to Washington in January.”

And there she was, holding a sign reading “The future is female” with a little stick figure of a woman drawn on it, marching with her best friend and best friend’s daughter. They’d driven up the night before and stayed with my mom’s sister in Arlington; they woke up early so they could get a spot close to the stage.

“The last true conflict of cultures,” Joan Didion once wrote, was “between the empirical and the theoretical.” At the time, she was discussing the 1988 ascendance of Jesse Jackson, “a candidate whose most potent attraction was that he ‘didn’t sound like a politician.’” Though he’d never held public office, Jackson was a well-known reverend and civil rights leader, and used his significant following to damn near institute a hostile takeover of the Democratic Party. Didion observed that his supporters “were willing to walk off the edge of the known political map for a candidate who was running against, as he repeatedly said, ‘politics as usual,’ against what he called ‘consensualist centrist politics’; against what had come to be the very premise of the process, the notion that the winning and maintaining of public office warranted the invention of a public narrative based only tangentially on observable reality.”

These words bear repeating, because they help remind us that on some level, the American impulse to elect a Trump-like figure has existed for decades. Our government was designed to do things slowly—it was better to function effectively but at a snail’s pace, the Framers supposed, than quickly and disastrously. This institutional languorousness, no matter how successful at preserving democracy66More or less. in the long run, can be maddening in the short term, especially when people feel like things are going poorly for them. But as Didion wrote a few years later, “[in] the understandably general yearning for ‘change’ in the governing of this country, we might pause to reflect on just what is being changed, and by whom, and for whom.”

Donald Trump isn't necessarily a truly evil man—just an extremely dumb, selfish man who needs more therapy than he has hours left on this earth and is only capable of conceptualizing the world in relation to himself. Just as he quickly came to redefine the term “fake news” to mean “any story Donald Trump doesn’t like,” it’s clear he sees the word “American” as meaning “a person who agrees with Donald Trump.” Given this brand of circular logic, it makes sense that Trump would think that millions of people had voted illegally in November, and all of them for Hillary Clinton. But when it comes to the free world, it doesn’t matter if you hand the keys over to the devil or a man-baby. Both can easily steer the whole thing into a ditch, especially if the man-baby never pays attention during his CIA briefings.

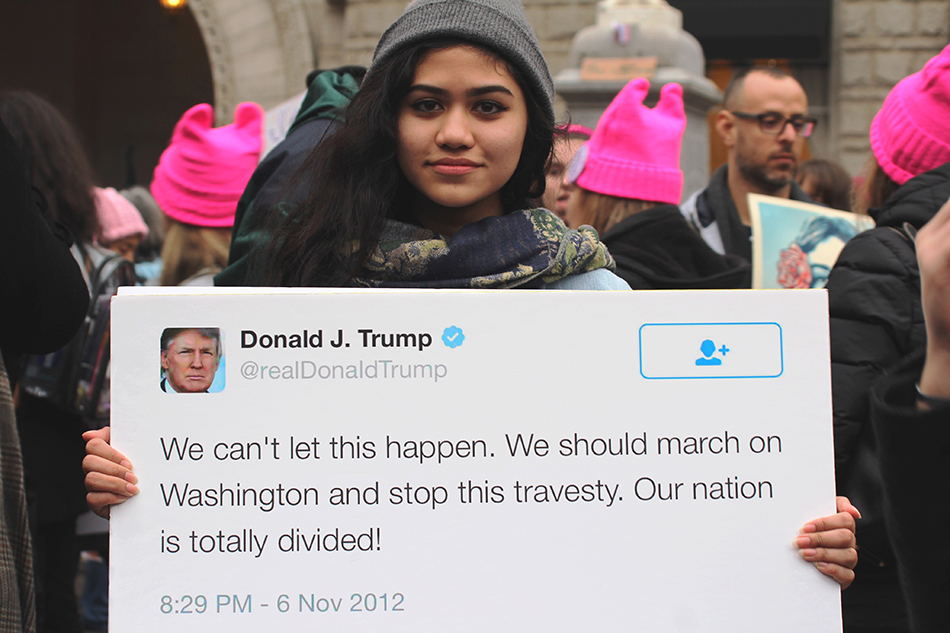

This goes a long way towards explaining why Trump seems bent on insisting his was the most-viewed inauguration in history. Sure, there might have been more people present at the Women’s March than at his own swearing-in, goes the Trumpian line of thought, but think of all the people watching on TV and the Internet! All of those people were tickled pink. Those few hundred thousand ingrates who walked by his house on Saturday were just a drop in the bucket compared to everybody who was watching the inauguration. And besides, those people don’t even like Donald Trump, so how can we even be sure they’re American?

I don’t think Donald Trump saw my mom, or the hundreds of thousands of people like her, coming. As president, he encapsulates so many of the problems we face—economic inequality, racism, sexism, xenophobia, transphobia, the coldness of global capitalism, the massive advantages granted to those born into privilege—that on some level, he can’t help but bring people together.

Down at the Women’s March, it’s so packed that text messages aren't working. The same people who were hawking bootleg T-shirts at the inauguration are back, this time armed with pink knit hats, Women’s March T-shirts, and pins that say CHUMP. Women wearing backpacks made of duct tape and see-through plastic walk through the crowd, handing out copies of Langston Hughes’s “Let America Be America Again.” Some kids play catch with an empty Gatorade bottle, while someone walks by holding a sign with a picture of Prince and a lyric from “1999” airbrushed onto it. Next to a stairwell, pair of Black women smoke a joint discreetly, prompting a tragically clueless white dude to ask, “Who’s got that good weed?” in a voice meant to indicate that he, too, would like to smoke some weed, but to everyone else might as well be a police siren. They scowl at him and put it out. A friend I haven’t seen in years walks past. We make eye contact, clasp hands for a moment, and move on. Nearby, a mother sits on a wall, her son napping on her outstretched legs. She slips a pair of gloves on his hands. Somehow, he doesn’t wake up.