Twenty years ago, during a particularly soggy late-summer hurricane season along North America’s eastern seaboard, a 62-year-old Hofstra University professor named Silvia Federici published one of the most influential feminist texts of the 21st century.

That book, Caliban and the Witch, traces the emergence of witch hunts throughout medieval Western Europe amid the transition from serfdom to proto-capitalism. It argues that the “primitive accumulation” of wealth formalized the persecution of women too old, weak, wily, or uncooperative to birth and rear the workers needed to amass riches for those in power—and to issue a warning against others who dared to follow their lead. “The witch was the first rebellious woman, refusing the social order imposed upon her and claiming her autonomy,” Federici wrote.

This recontextualization of a dark and seemingly distant chapter of history nods at a premise that has been central throughout Federici’s work: that the subjugation of women is baked into the very foundation of the capitalist system, inseparable from ongoing crackdowns on reproductive autonomy and sexual freedom and, not unrelatedly, the constant devaluation of care work. In leftist intellectual circles, Caliban was hailed as a triumph. Among the wider public, it was mostly ignored for nearly two decades.

Federici knew this would be her defining work; it had been in the making since the mid-1970s. But when the book was released into the wider world, she wasn’t thinking much about its reception. She’d caught wind of a rumour that Hofstra planned to dismantle New College, her academic home and one of the last remaining holdouts of a crop of experimental, interdisciplinary humanities programs formed under the auspices of otherwise traditional North American universities in the 1960s. Despite her impatience with the ideological risk-aversion of the university at large, New College had offered Federici an oasis of intellectual freedom—and hard-won financial security—for the past seventeen years. There was little comfort to be found in the state of affairs off campus, either. The U.S. was at war in Afghanistan and Iraq; far away in her native Italy, Federici’s older sister was navigating the care of their ailing nonagenarian mother.

For Federici, the personal and political have always been tightly interwoven—the intimate dramas of relationships and routines patterned by the machinations of power and, in turn, rebellion. Her calling is to pay attention. Her preface to Caliban was explicit in the project’s aim “to revive among younger generations the memory of a long history of resistance that today is in danger of being erased.” Preserving this record “is crucial if we are to find an alternative to capitalism,” Federici wrote. “For this possibility will depend on our capacity to hear the voices of those who have walked similar paths.”

This worldview has propelled a feverish pace of production that’s easier to understand from the vantage of fervent religiosity than that of the duty-bound North American worker who hopes to get ahead. Federici is motivated not by acclaim or potential advancement, or even the fickle immortality of legacy. Her drive is the compulsive monasticism of a true believer in the revolutionary cause. Federici’s endgame is a society that isn’t dependent on capital or state, and which operates on a foundation of interpersonal cooperation, care, and collectivism.

When we met at her home in Brooklyn on a crisp, sunny evening last November, nearly two decades post-Caliban, Federici, straight-backed and wiry, greeted me brightly with an assertive handshake and asked whether I wanted coffee or a glass of prosecco. In her apartment, life and work compete for square footage; her living room is strewn with books, pamphlets, and piles of correspondence. “Everything is out because I’m bringing some boxes to Brown,” she explained in apology for the disarray, nearly eliding its implications—that an Ivy League university was anointing the material record of her labour into its archive of feminist history.

But institutional validation has never rated among her concerns. Though she retired from teaching in the mid-2010s, Federici is as busy as ever with speaking engagements, activist organizing, and writing—always writing. She is also, as ever, unsettled. The streets, once again, echo in protest of American taxpayer-funded bloodshed overseas, this time in Gaza. It is now her partner and intellectual collaborator of more than fifty years, the philosopher George Caffentzis, who requires round-the-clock care, his mobility and motor function sharply diminished by Parkinson’s disease. Despite being three years Caffentzis’s senior, Federici is his primary caregiver.

While Federici wasn’t looking, though, her life’s work finally reached the mainstream. In 2020, the pandemic’s lockdowns momentarily deprived white-collar workers of the childcare and sundry domestic services they normally outsourced to lower-paid workers, most of them Black and Brown women. A cadre of well-off women, and not so well-off women, found themselves working an untenable double shift, caring for kids and elderly relatives and tending to the unending drudgery of housework, some for the very first time. Seemingly overnight, the lean-in generation became interested in what Silvia Federici had to say.

In the span of a peak-pandemic year, Federici was profiled in the New York Times and The New Republic and name-dropped in The Atlantic—three holy texts of the American liberal establishment. During the same period, Caliban and the Witch, which had originally been released by Autonomedia (a small, Brooklyn-based radical publishing collective made up of several of Federici’s longtime friends and political co-conspirators), was republished as a Penguin Modern Classic. As she approached her eightieth birthday, Federici was suddenly in a peculiar position. Somehow, she’d become a mainstream feminist intellectual—that is, until the world reopened, the nannies resumed their posts, and the zeitgeist returned from whence it came.

Federici barely registered these shifts. Although she concedes to fielding “many calls for interviews for this and that” in recent years, she sees little common ground between her understanding of feminism and that of the popular feminist orthodoxy.

“What is feminism today? What is the fight?” she sighed, the silver rings on her fingers dancing with gesticulation. “Is the fight to join the army so we can go and kill the children of other women? Is the fight to go to Wall Street so that we can put in financial policies that are impoverishing part of the world?”

On this and other matters, she expresses her distaste in the sombre, sometimes meandering polemics of a prodigious thinker whose waking life has poured into constructing interconnected webs of argumentation—and who is used to holding court. “In New York, when I see those skyscrapers, I see blood coming down from them: the misappropriation of wealth, the financial system always backed up by the military,” she continued. “These days, I am thinking a lot about feminism and war.”

Feminism, finance, and war. It’s a tidy summation of the lens through which Federici views the world. Feminism, as she understands it, is a natural point of convergence for the innumerable political movements working against the injustices wrought by global capitalism, like a hub reinforcing the tension of so many independent spokes. She rejects the loosely defined feminist ethos most common throughout the West, a limp mission of so-called empowerment whose chief pursuit is equal access to the farthest limits of wealth and status under the banner of an exploitative, power-hoarding state. No matter its critics or the accumulation of derisive labels—corporate feminism, girlboss feminism, lean-in feminism, white feminism—a feminism of self-interested striving is the order of the day. It is, in so many words, the feminism of selling out.

Federici has never sold out. Keen on narratives of resistance against the wiles of capital, her work is an awkward fit within the increasingly corporate university; in women’s and gender studies departments, her scholarship has often been sidelined in favour of the less materially grounded, poststructuralist analyses of identity performance. Although she has been cited admiringly by a litany of notable thinkers—the superstar gender theorist Judith Butler and novelist Rachel Kushner among them—she tends to be relegated to the footnotes of popular feminist discussion.

For these and other reasons, Federici occupies an unusual position in the public intellectual consciousness. At 82, she is somehow both niche and seminal, a marginal giant. Her more than fifty-year career presents a parable of the pitfalls facing radical scholars and artists who refuse to barter ideological compromise for material security, illuminating the fault lines of anti-establishment dissent and the practical limitations of free speech within the marketplace of ideas. Depending on the beholder, she is a model of vanishingly rare integrity or a cautionary tale of its steep personal price.

***

In Federici’s telling, her political orientation was a biographical inevitability. The second of two daughters, she was born in the northern Italian city of Parma in April 1942, against the backdrop of bombs and Hitler’s Final Solution. Recalling her childhood, she told me, “I knew from a very early age that the world was an unjust place.”

But her childhood also provided a glimpse at how a person’s material conditions—their access to land, money, or an education—could reshape their social circumstances. Shortly after Silvia’s first birthday, the Federici family fled the constant bombardment of Parma and found refuge on a small farm in the Lombardian countryside. A pair of unmarried sisters managed the farm; it offered them an unusual measure of freedom in a society that was otherwise “patriarchal and fascistic,” as Federici describes it.

Similarly instructive was the family’s return to Parma in 1955. Unlike the Catholic Church–dominated culture that prevailed through much of postwar Italy, Federici’s hometown was a longstanding leftist stronghold. A popular legend of Federici’s youth recalled the local women crushing communion wafers into their omelettes during the war as a gesture of gleeful sacrilege.

But like the rest of Italy, and elsewhere, Parma was decidedly less iconoclastic in its gender relations. Federici’s household was no exception. She saw her father, a high school philosophy teacher, as “the exciting person” who earned the wages that supported the family while her mother managed the home and disciplined the children, with little fanfare and even less material reward.

“My mother was the one who said, ‘Have you cleaned up?’ ‘Pick up your sweater.’ ‘Do this.’ ‘Don’t do that,’” Federici recalled. “My father was above those things. He would come home and bring stories. He knew about history, was educated. My mother was not.” Bookish and rebellious, Federici’s determination to avoid repeating her mother’s fate lit a fuse.

Upon completing her degree in modern languages and literature at the University of Bologna, getting out of Italy was the next order of business. In 1967, she won a Fulbright scholarship to pursue doctoral studies in philosophy at SUNY Buffalo, where she promptly threw herself into student organizing, the cresting anti–Vietnam War effort, and the civil rights movement. She was also, from afar, alternately writing, editing, and producing translations for a handful of radical journals in both Italy and the U.S. It was through this work that Federici encountered the writing of the Italian feminist Mariarosa Dalla Costa, who asserted that in capitalist societies, women’s exploitation and economic dependence on men sprang from women’s unpaid labour in the home. Federici and Dalla Costa joined forces and, alongside feminists Selma James and Brigitte Galtier, co-founded the International Feminist Collective, or IFC, in 1972.

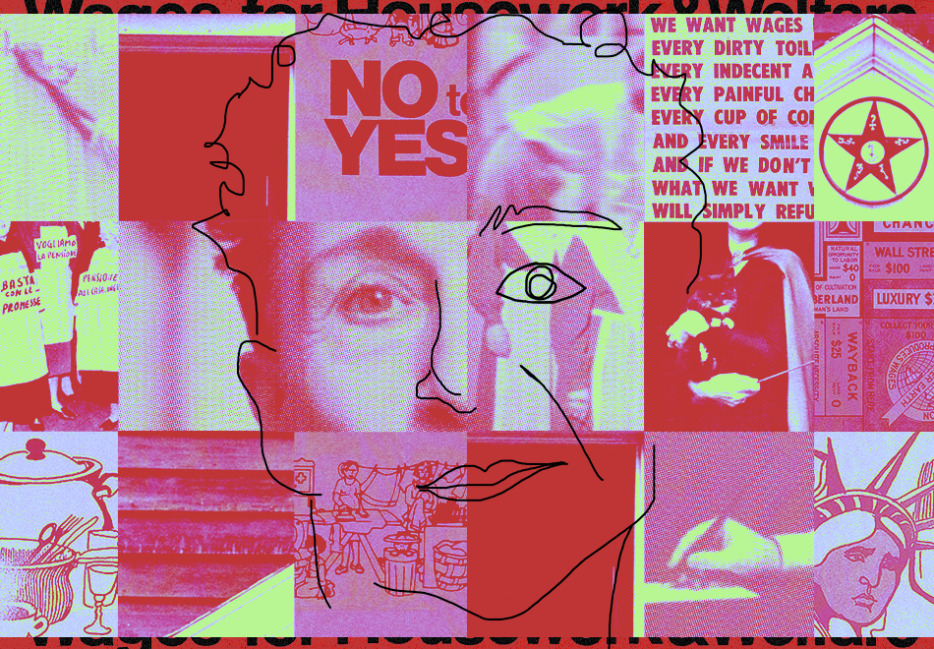

The IFC’s central project was Wages for Housework, a global movement that sought to call attention to gender inequality by zoning in on women’s unpaid “reproductive labour”—the cooking, cleaning, and caregiving that must be done in order to produce anything and everything else—and by loudly refusing to do it. If Caliban is Federici’s magnum opus, the writing she produced under Wages for Housework is Hammurabi’s Code. “We must admit that capital has been very successful in hiding our work,” she wrote in 1975. “It has created a true masterpiece at the expense of women. By denying housework a wage and transforming it into an act of love, capital has killed many birds with one stone.”

Federici and her co-conspirators viewed the rejection of that work not as an endgame unto itself but as a tool for consolidating power between and among women. They wanted to chip away at women’s dependency on men’s wages and, especially, at their participation in the capitalist system. It was a vision that reimagined labour as a shared pursuit, one designed to sustain the people whose work yielded the goods and services they needed—subsistence-level production by and for communities, as opposed to wealth amassed by workers for the enjoyment of a lucky few, and at the expense of the far less fortunate majority.

Federici was in the process of getting Wages for Housework’s New York chapter off the ground when she met Caffentzis. An erstwhile beatnik born in New York City to Greek-immigrant parents, he was finishing a chapter-by-chapter Marxist rebuttal to Paul Samuelson’s Economics (for fun) while simultaneously completing his doctoral dissertation. The two became roommates and, before long, a couple. Almost immediately, the relationship became inextricable from their collaborative efforts as scholars and activists willing to forgo economic stability—and, sometimes, physical safety—in service of their political projects. (A revealing, if potentially apocryphal, story still in circulation among several of the couple’s younger acolytes recounts them on a visit to Italy in the late 1970s, during a period of far-right terrorism now remembered as the Years of Lead, narrowly dodging a would-be assassin by hiding in an associate’s bathtub.) They remain, to friends and colleagues from across the disparate pockets of their lives, an intellectual and ideological unit: Silvia and George.

Their respective PhD programs ejected them into Ronald Reagan’s America, the Cold War’s last hurrah. It was a less than auspicious moment for a pair of communist philosophers trying their luck on the academic job market. They cycled through a succession of short-lived teaching placements before decamping to Africa. Each accepted lecturer positions at Nigerian universities: Federici in Port Harcourt and Caffentzis in Calabar, 220 kilometres and a full day’s journey apart. For much of the next thirty years, their relationship unfolded at a distance—a devotion meted out in stacks of multi-paged letters. “I MISS you SOOOOO MUCH!” Caffentzis wrote in one such missive, dated April 1987. “How I would LOVE to hear your indescribably Silvia voice calling from the bathroom, the study, the living room, outside in the parking lot, or even from the roof!”

All the while, their work developed in tandem. They co-founded the Committee for Academic Freedom in Africa, a coalition of scholars who had been squeezed out of their jobs at African universities amid mounting government repression, largely at the hands of corrupt regimes backed by the U.S. and Europe.

As political volatility roiled across Africa, both Federici and Caffentzis continued to apply for academic job openings wherever they cropped up. There was radio silence from Singapore; a rejection slip from Walla Walla, Washington. Then came a stroke of serendipity from Hofstra University on Long Island, an easy ride by commuter rail from the couple’s on-again, off-again home base of Brooklyn. New College—a unique, individualized liberal arts college that operated independently of the university’s official humanities and social sciences departments—needed a philosopher, and someone had passed along Federici’s name. She was a formidable scholar, her future colleagues were assured. However, the recommendation came with a word of caution: “She’s the angriest woman I know.”

***

Few people are activists in the truest sense. If you are reading this, there’s a good chance you’ve never met one. Many may participate in activist actions at one point or another—attending the occasional rally, sharing the odd meme, bemoaning the presence or absence of other people’s displays of affiliation. But to be an activist through and through is to swim single-mindedly against the current of common wisdom. While the activist builds networks among like-minded outsiders, they also burn bridges with the people and institutions best positioned to grant them access to a livelihood or the currency of influence. The activist’s worldview implicitly undermines the values and aspirations championed by the society at large, which probably includes many of the people around them. To be an activist is to accept others’ disdain as the price of upholding principle, to run the risk of ruin. It’s an alienating and precarious path.

Only a few lucky and talented activists are able to carve out a sustainable space for themselves in academia. This is where the reality of the activist-scholar sharply diverges from common misconception. The North American university is often painted as a hotbed of radicalism. Conservative and free-speech libertarian pundits seem particularly wedded to the belief that campus ideologues pose a clear and present danger to impressionable young minds, sowing censorious armies of reactionary wokeists. But this caricature obscures a long-standing tension between academic freedom and the rigid bureaucracies endemic to higher learning institutions.

That tension has only escalated over the last four decades, as privatization nudged universities to adopt corporate-management models that eschew investing in the liberal arts in favour of fields presumed to be commercially viable, such as computer science. All the while, as they’ve grown beholden to the interests of financial backers, academic institutions have become swift to crack down on any controversy that might risk their purse strings. (Over the past year, many universities’ panicked responses to the pro-Palestinian sympathies of students and faculty have made this dynamic much more visible.)

Though it was far from utopian, New College largely bucked the trend. It gave Federici something like a safe haven. She designed and taught courses on Marx and radical thought; art and revolution; women in the third world. She also built the theoretical framework that eventually culminated in Caliban and the Witch, advancing her case that the losses women incurred through capitalism were steeper and further reaching than the ostensible liberties they won with the free market, and particularly in the global south. Her work posed a direct challenge to popular understandings of what women’s liberation looked like.

“We had a ton of freedom relative to the rest of the university, which is why I think she was able to be somewhat at home there,” recalled Linda Longmire, a Hofstra University professor of political science who was a close colleague of Federici’s throughout her two decades at New College.

But Federici didn’t seamlessly blend into the fray. Her scholarship condemned the Western global order and U.S. foreign policy, which some of her peers found politically, and perhaps personally, threatening. She was also openly reproachful of the way these subjects were handled within the academy itself. In her written contribution to Enduring Western Civilization, a 1995 collection of scholarly essays that she also edited, Federici derided “Western Civilization” (scare quotes hers) as both a concept and an academic discipline. “More than faithfulness to any particular cultural claim, what has allowed ‘Western Civilization’ to endure has been the exceptional backing it has received both from governmental institutions and from a body of conceptual bricoleurs who, from time to time, have retooled it to meet the challenge of its opponents,” she wrote, not-so-subtly implicating at least some of her peers in the ivory tower.

“Silvia wasn’t always easy—she was relentlessly critical,” said Longmire. “But I appreciated that, because everything needs to be criticized, particularly when you’re working within a structure.” Federici called to her mind a slogan attributed to the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci: Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. She saw the world for all its bleakness and embraced the challenge to imagine something better.

“But could she have survived in the philosophy department over on the other side of campus? Probably not,” Longmire said. “I think there would’ve been a whole lot of pushback.”

Whether or not she thought about it, Federici embodied the central conundrum of activists and the movements they serve—the double-edged sword of unwavering iconoclasm. Her refusal to back down fortified the totality of her work. It also, almost certainly, foreclosed on the degree of buy-in that would be required to bridge theory into practice at scale.

Ideological tensions notwithstanding, faculty members’ letters of support for Federici’s tenure and eventual promotion to full professor convey broad admiration for her intellect and the scope of her scholarship, not to mention the prodigious volume of her written output. Most of her colleagues praised her global outlook and her fierce dedication to her students, several of whom were said to have described her courses as eye-opening. Nonetheless, Federici was in her early fifties before she finally received tenure. At 60, she still hadn’t been promoted to full professor.

It’s unclear if Federici ran into bureaucratic roadblocks or professional penalties, or if the logistics of self-promotion were simply low on her list of priorities; likely, a little of each was at play. Friends say she and Caffentzis rarely discussed the ins and outs of their careers, much less to complain about their status at their respective universities. Whatever grievances they may or may not have privately held were likely tempered by the people they knew in Italy and Africa who paid a far greater toll for their dissent. Some were imprisoned; others, assassinated. Besides, the couple didn’t need to rely on academic channels to advance their scholarship; they each published largely with political presses. Although both were rigorous scholars who were rightfully respected in the university, their autonomy preserved the ability to resist compromise.

But those who knew Federici professionally saw the opposition she was sometimes up against, particularly from colleagues with whom she was at ideological odds. Longmire admitted that “there were some intense conflicts” between Federici and other faculty members, an observation echoed by others in Federici’s academic circles. “Dr. Federici has relentless courage; she has never wavered or faltered in her wrestling for justice, in spite of the criticism and even opprobrium received from colleagues and others,” wrote the historian Mario Fenyo, who worked with Federici at the University of Port Harcourt, in a 2002 letter of recommendation.

Fenyo’s letter points to the irony in Federici’s ostracism. Her worldview is radical precisely because it advocates togetherness. In this vision, people look out for one another and jointly absorb the burdens of care and domestic toil. They work toward building communitarian relationships—the creation of commons. What Federici proposes is less a blueprint for a utopian alternative society than an escape route from the solitary grind of getting by. Interdependency is the revolution.

It also imposes a complete departure from the social order circumscribed by markets and the state. When a new swath of readers discovered Federici’s work in lockdown, many saw themselves in her analyses of unpaid care work. She gave language to their private frustrations and situated them within a broader political arena. She showed them they were not alone. But across capitalist societies, women have struggled to internalize en masse that their collective problems likely call for collective solutions.

Federici has a few theories as to why. For one, today’s feminist goals are far less clear-cut than during her generation’s coming-of-age, when the subservient housewife presented a sharply drawn target for all that must be renounced. The migration of movement organizing into digital spaces has further muddied the view of a joint objective, imposing the very-online liabilities of distractibility and reactive splintering onto activist endeavours. These shifts in culture and technology have made some aspects of feminist organizing easier, yet have also appeared to discourage pockets of collective actors from finding one another.

“The feminist movement is so segmented that it appears we don’t have a common ground,” Federici told me. “So that’s been part of my struggle as a feminist, to say we do have a common ground. The feminist movement is the movement that is most apt to create a common ground. Because if you start from the question of reproduction, reproduction is to do with housework, sexuality, healthcare, ecology, food production, air quality. So that is actually the ground where more movements can come together, because we are all connected.”

***

These days, Federici is setting her sights south. That’s where the real feminist action is brewing, she says. “When I look at the way women organize in Latin America, I see that they make a connection to so many realities that women are living: domestic work, ecology, the destruction of the environment, the debt economy,” she told me. She remains cautiously hopeful that feminists in the U.S. will take note.

For the past several years she has embedded herself within various Latin American feminist organizations, including the Argentina-based Ni Una Menos. That group’s founding member, Verónica Gago, is a point of contact for Federici’s latest ongoing feminist project, Feminist Research on Violence. The New York City–based group, which began in 2017, is less a formal entity than a close circle of friends who happen to also collaborate on ad hoc political writing. Many of its members are from Spain and Latin America, and several have known Federici since the days of Occupy Wall Street.

Alejandra Estigarribia, who joined the group shortly after moving to New York City from Paraguay, observes that Federici’s approach to building community much more closely resembles the open-door policy of an extended Latin American family than that of the typical New Yorker, down to the simple everyday practice of having people over for dinner. Federici not only imagines a more communal way of living but creates it. The cross-pollination of ideas and conversations that spring organically from her relationships, in turn, feed her writing.

“It’s the act of commoning, or creating commons, as a way of life,” Estigarribia said.

That way of life has come full circle. On Federici and Caffentzis’s living room wall hangs an assortment of family photos and mementos: Federici’s parents on their honeymoon in 1930s Italy; a sun-bleached colour print of a little girl, her niece, who is now in her fifties; Federici as a grinning, sprout-haired infant on her older sister’s lap, “Parma 1942” embossed on the bottom right-hand corner; an original Wages for Housework Campaign flyer. Nestled among these is a poster for a joint talk by Federici and Caffentzis, printed with black-and-white portraits of the pair’s younger selves. On the left, Federici’s face is turned at a forty-five-degree angle from her beholder and an unlit cigarette extends from her lips. Her expression is at once nervy and pensive, the scholar and the militant in full and equal view. On the right, Caffentzis faces the camera head-on, the top two buttons of his shirt undone and his dark hair long and full.

Caffentzis has always been the yang to Federici’s yin. Where she is gregarious, he is reserved. Where she is “very, very talkative,” as their friend Susana Draper puts it, he is “very, very quiet.” Their senses of humour are complementary, but distinct.

Throughout my conversation with Federici last fall, Caffentzis sat in a wooden chair beside me. Every so often, the side-by-side likenesses of the couple’s youthful counterparts caught my gaze in the middle distance. Now 79, Caffentzis has a slight build and gentle appearance. He relies on Federici’s assistance for his most basic necessities, softly interrupting our conversation when he needed help visiting the bathroom or adjusting his seat.

Though Federici ably supported the full weight of his body as they moved from room to room, she mused at the peculiarity of her predicament. “I often think, I am [in my 80s] and now have a child 110 pounds heavy. And I don’t have anybody else.” She turned toward Caffentzis. “Eh, my love?”

“Yeah,” Caffentzis said quietly, his cadence measured and deliberate. “Everything Silvia says is true. I also think that it’s important that we recognize the fact that we can’t operate—not only our lives here, but also even in a reorganized system—and still leave that question open: How do you move that 110-pound fellow from point A to point B?” Caring must always be done and, no matter the configuration, someone must always do it. Federici’s most radical insistence may also be her most obvious: that no quantity of broken glass ceilings will resolve this intractable riddle.

Federici’s position on reproductive labour has long since evolved from her Wages for Housework–era stridency. It is a reality of life that she now takes in stride. Caffentzis comes along wherever her conferences, rallies, and speaking events may take her. Late last summer, they spent forty days in Europe. In the weeks after we first spoke, they made stops in Brazil and Germany. She won’t go anywhere without him.

On every trip, friends from Feminist Research on Violence join, too. Their relationships with Federici function on two levels: as the joint members of an activist collective and, separately, as a chosen family. Lately, the latter role has taken precedence. On multiple occasions that I’ve phoned Federici’s landline, one of the women picked up. During my time in Caffentzis and Federici’s apartment, they called to check in and make plans. The women visit every week, either individually or in groups, and help with whatever they can.

Friends say it hasn’t always been easy to convince her to accept support. Begonia Santa-Cecilia, an activist and visual artist who has been involved with Federici’s women’s group since its inception, attributes this in part to a streak of “old-school Italian” proudness and, in part, to the reflexive grasp for independence that so often emerges when a person crosses the threshold into old age. Still, with the limitations of Caffentzis’s illness and some coaxing from her inner circle, Federici is learning to share her load. In a poignant turn of events, the twilight of her life has become the very model of collective care that she spent a half-century putting to paper.

But if Federici intends to slow down, she gives no indication of it. There is too much work to be done. “You know, they say the older people become, they become more pacified with the world,” Federici told me. “Well, with me, the opposite is happening. The older I get, I get more enraged.”