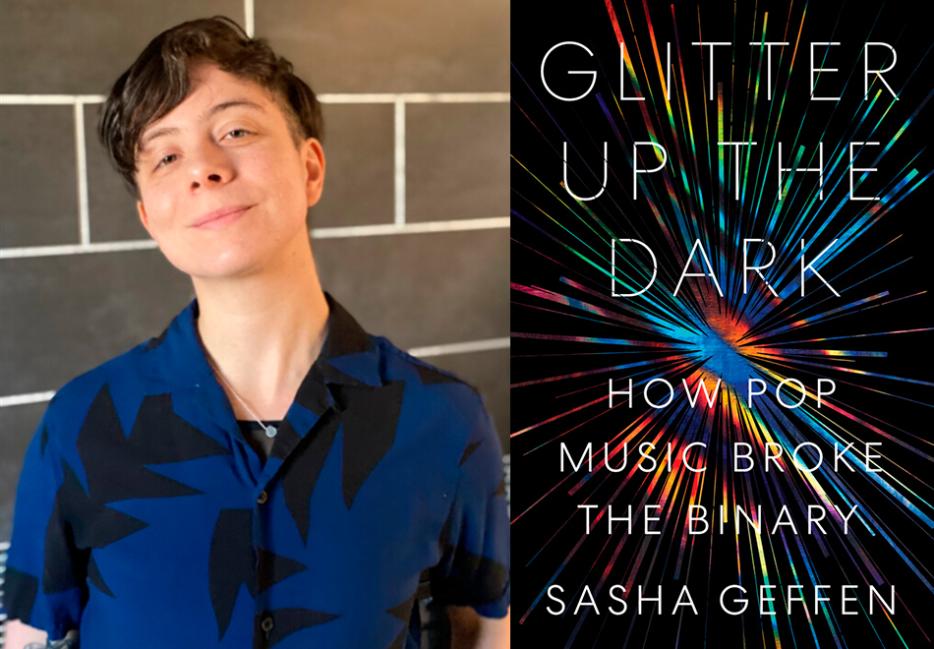

“Mr. Presley has no discernible singing ability,” the New York Times critic Jack Gould fumed in 1956. “His one specialty is an accented movement of the body that heretofore has been primarily identified with the repertoire of the blonde bombshells of the burlesque runway.” In their new book Glitter Up the Dark: How Pop Music Broke the Binary, the slyer critic Sasha Geffen notes that he could’ve just called Elvis a male bimbo. Geffen scours a century of music for these glinting crystals, from 1920s blues singers to early synth experiments, Beatlemania to grunge, with Prince as a genre unto himself. Even the most harmonic among them carried notes of dissonance, rupturing the carefully gendered voice.

Geffen invokes canonical artists with wan mischief—“Titless, he struts like he’s got his tits out for all to see,” they write of Iggy Pop—and keeps finding curious historical details, like how Klaus Nomi settled on his abstracted outfit because a full costume would’ve been too expensive. They also hit on the ways capitalism tries to recuperate each moment of subversion: “If it can’t get rid of them, patriarchy tends to devour its threats.” But that process never moves in only one direction, and Glitter Up the Dark lovingly describes the affinities drawn together by the act of listening. “Inside a song,” Geffen writes, “every singer is exactly who she says she is in the moment her voice passes through her throat.”

Chris Randle: After the prologue where you talk about early modern American music, like, the blues, Harlem Renaissance people, why did you decide to start the book with the Beatles, and specifically their first pop covers? Were you looking to invert the canon?

Sasha Geffen: I don't know if it's an inversion, necessarily, but I wanted to point to a moment that I saw as the beginning of pop culture and fandom as I think it still is now. This gathering of attention around a band on a mass scale, with heavy consumerism involved too. And I thought the Beatles were a pretty reliable starting point when it comes to pop as a mass cultural phenomenon, because even though pop is 50, 60, 70 years old, depending on when you want to mark it, that's the first time that someone makes dolls out of a band that I could find. Action figures, wigs, merch. And it also seemed to be a sea change in the way that fans oriented themselves around bands, taking bands as these objects that generated identity. So it wasn't that I see the Beatles as the beginning of pop music, because they're not, but they did seem to mark a shift that made a good starting point for this discussion.

Yeah, my sense is that, at least before World War Two, stardom didn't work in quite the same way. Like, more often the songs would become famous and the stars would be Artie Shaw, or whoever.

Right, it feels like the song was more the defining unit of liking pop music. And the Beatles came along in a decade where the teenager had just been established as a post-war phenomenon, where there was all this money concentrated in the hands of young white people, and a lot of capitalists were eager to draw it away from them by any means possible [laughs]. And Elvis kind of started with that too, but I think the Beatles really raised the stakes to another level, the level of urgency around Beatles fandom was unparalleled at the time.

Even just, like, the hair. I actually love how much attention you lavish on that [laughs].

It's more interesting than the music, I think. Just the way they looked is so fascinating, it's so specific.

There's an old Hannah Black tweet that went, "Gender is 50% hair."

It's true. It's the first thing that people notice when they see you.

Do you remember a moment earlier in your own life when you saw a music video, or heard a song on the radio, and sensed everything turning liquid in that way?

Yeah, I can tell you my Savage Garden origin story! That was my first experience with fandom, and it's really dorky. When I was maybe nine or ten years old, I was really into being online, and went to all these different goofy fandom things, games, virtual pets. That whole '90s culture of having your own colorful home page: "Here's this GIF of a cartoon cat that I adopted from someone else's website." And one of the sites I went to had this auto-playing MIDI rendition of the Savage Garden song "Truly Madly Deeply." I would hear it every single day, and I didn't know what it was, and it was just a melody without lyrics so you couldn't look it up. Then I was on a plane, listening to the looping airplane radio, and that song came on, and I was like, holy shit, it's the song from the cat website that I visit all the time.

There was a pre-recorded announcer who identified the band as Savage Garden, so I went home—I think one of their newer songs was playing on the radio too, from the second album. So I convinced my parents to buy me both albums, and I had this ritual of putting in the first self-titled record, the little orange CD, into my mom's computer right before I would go online, and go into my chat rooms pretending to be this gender-morphing fantasy creature. I think that voice triggered something in me for sure, because Darren Hayes's voice is so effeminate and so androgynous, so interestingly coarse. It's very high, and he uses his falsetto, but it also feels kind of crimped and faltering at points. There's a lot of failure hard-coded into it.

In retrospect I could see that speaking to my own bodily situation, of being about to go through puberty not really knowing what I was in for, and excited to become a sexual being but also obviously not doing it the right way, according to the feedback I got from my peers [laughs]. Being told that my relationship to myself was weird or wrong or gross, all that fun baby gay shit where you don't know what's happening yet, but everyone's like, "You're disgusting." And you're like, "I'm just here trying to be a person, I don't know what's happening." So that band was like a sanctuary for me at 11 or 12, I was obsessed to the point where it was my schtick. When you're in middle school and no one knows what to do with you, they just assign you a schtick.

I had a VHS and a DVD of their music videos, and I just watched them obsessively. The "I Want You" music video, I think I write about it in the book, because that was a big one for me. He's got that gross chin-length stringy hair, looks really young and androgynous, he's in this cool cyberpunk environment. I actually got my hair cut like that, or tried to, it didn't really work because I've got Jewish hair. I had printed out this black-and-white photo of Darren Hayes at his most androgynous, and I brought it to the person who cut my hair at the time like, turn me into this please. That's kind of the root of my whole desire to see the gender in music, I guess, because they were both so intricately bound up for me from a young age.

Was there anything that turned up from research that really surprised you? I love the detail about Wendy Carlos, that she had to do her first publicity appearances in male drag.

Yeah! That was a fun one. I guess I didn't know a lot about Alice Cooper, especially his early work and early appearances, how he was spouting lines that sound very much like Tumblr-queer jargon now. "Everybody has a little male and female in them, it's a biological fact." Which sounds like an infographic you'd see among social justice communities, but he was saying it to be provocative, because in the early '70s you couldn't just do media interviews and say that shit without making some people upset. And of course his whole getup was designed to be freakish, it wasn't like Alice Cooper was wearing makeup to be pretty, it was to look garish. What also surprised me, kind of from that same era, is how you see the young proto-punks like the Stooges being really into the Beatles, because they're so frightening to their surroundings. Like being into Nazi imagery and being into Beatles imagery were equally provocative.

It's mind-boggling to me, because the Beatles seem so tame and anodyne now, it's like dad culture. But people would get catcalled, you'd get called "Beatle" on the street if you had long hair with the venom of a slur. That shifted my preconceptions around these eras I was studying. I feel like you don't always know the norms of a particular musical era, even if you know the music pretty well, so reading a bunch of contemporary interviews was really interesting, because you could see the shock happening in real time [laughs]. Seeing very square, very straight music journalists getting up in arms over what Lou Reed or Alice Cooper were doing was funny and revealing.

You spend a lot of this book writing about the ambiguity of voices. Why do you think they're so malleable in that way?

I think just the fact that they're the one musical sound that comes directly from the body, and that the body by necessity has to be malleable and flexible. Humans are very adaptable, and at least in hearing communities we communicate primarily through voice—communication isn't just done through actual words, it's intonation, accents, all kinds of subtle variations in the way voice is used. I think that extends to music, maybe it's even intensified in music, because music is this heightened dream-space. When you're singing it's not the same as speaking, it's this gauzy detachment from linear reality, where the song is looping in perpetuity, if that makes sense. Especially since recording began, individual vocal takes are frozen in time forever, kind of in their own reality. So I see voice as an opportunity to try out ways of being, ways of expression, that don't necessarily have to be rooted in the material conditions of your life. You can sing an alternate reality, an alternate mode of relations, and it doesn't mean you have to be that person that you're playing.

It's almost embodied and disembodied at the same time. Like, an impression of the singer with no visual.

Totally. Yeah. And in many cases an impression of a singer who's no longer alive, who no longer has a body to which that voice corresponds, but this ghostly after-impression of their voice still lives on. I think that makes it ripe for a lot of tension and conflict, and that's where I see a lot of these themes of gender-weirdness coming out.

Early on you mention those wax-cylinder recordings of the last castrato, Alessandro Moreschi, and it made me think of—do you know this book called Making Sex, by Thomas Laqueur?

I think you've mentioned it to me before, it's on my list of things I should be reading but haven't yet, because I'm a very bad procrastinator and a slow reader. I've gotten better, but I get disillusioned. Sadie Dupuis [guitarist/vocalist of Speedy Ortiz] just posted her April books pile, and it was like eight books, and I'm like, shut the fuck up [laughs]. I've been inching my way through Faulkner and Alice Walker right now, these classics that were on my bookshelf, but I've been doing it every day, which is progress.

It's funny, because Making Sex is a book from the early '90s by this middle-aged cis professor that doesn't explicitly mention trans people at all ever, but it's about the endlessly changing and contradictory "scientific" definitions of sex. Starting with the Aristotelian one, where he was like, "Women are cold and wet, which corresponds with the elements of..."

Right, women are like 3D printers for the male form.

Laqueur writes that all of these definitions of sex contain claims about gender. There's a part on the Renaissance where he discusses various cases of intersex people, what became of them, the formal decision on their identity from the local duke or whomever. He says that, generally, "as long as sign matched status, all was well." And in so much popular music sign does not match status.

It reminded me of that great essay you did about robotic voices—I actually have this giant quote from it pasted into my phone: "When grafted onto robots, alpha masculinity becomes distended and uncanny; Robocop and the Terminator supplant organic masculinity with a hilariously overwrought form of butch. Others present a beta masculinity ripe with pathos: the tragically named Alpha from Power Rangers, whose neuroses constantly short-circuit him, or Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s Data..." I guess I'm wondering, how do you feel those cinematic robots relate to synth-pop and vocoders?

I think you see a lot of overlap in Laurie Anderson, who I write about in the book, who created a caricature of masculinity using vocoders and pitch-shifters, which was deployed to a subtle comedic effect. It's a character that she uses a lot throughout the early '80s to poke fun at the idea of competent masculinity, masculinity as the harbinger of the future and as the natural subject of America. The comic effect of roboticizing masculinity definitely appears there, like, how powerful can masculinity be if it's so easily mimicked by something that's not a man? And that's true for failing robots like Data, it's true for someone like Laurie Anderson, and I think more recently you see Dorian Electra working in a similar vein, where they're doing office drag and singing through vocoder about being a "career boy." Performing all these stereotypical male roles ... The idea that masculinity is kind of inherently comic, because it's so stilted and brittle, comes into play there. And robots are a good excuse to magnify that, because they're so easy to break, and ill-fitting in the role of human in a similar way that men are.

It's interesting that Daft Punk, the other artists who had a Billboard hit while dressed as robots, have always been smoothly asexual in their persona. But not the camp C-3PO thing, or even that Data type, more like the Terminator if it were just making house jams ... In the Prince chapter, you talk about him in these Sapphic terms, echoing Wendy & Lisa's own description of him as a "fancy lesbian." I was thinking about the inverse, divas with a homoerotic affect, like Madonna.

I couldn't find a way to slot Madonna in. There were moments, but I couldn't make them cohere into an argument, whereas Prince, the chapter could've been longer ... He was so specific with such widespread appeal. I don't know any other pop star who managed to be that consistently strange and opaque and elusive and still so massively popular. So insistent on his own displacement from his surroundings, in terms of gender, the way he produced his music, and his relationships with the rest of the band.

He's my favourite musician, and I find "If I Was Your Girlfriend" so moving in the way that it takes this fantasy of perfect mastery—Prince writing and performing and producing every element of every song, shifting between genders effortlessly—and crushes it down into the narrow intimacies of heterosexuality.

Yeah, and I feel like there's this longing for a feminized mastery within the lyrics, right? This caretaking that he doesn't necessarily have access to in his male form, as a man who loves women. There's this whole realm of mastery that he's sealed off from, and the best he can do is use his mastery of music to simulate it, or try to find a way in to pantomime it.

In the chapters on dance music, you write a lot about these distended experiences of time: The improvised circuit of DJ and dancers, the stopped clock at the Loft. It feels very appropriate now that we're living in this endless suspended present. What do you think distinguishes the two? Why is one of them euphoric and the other nightmarish?

There's a point to the former, right? Being in a place where there's a lot of sensory input, you're hearing music that's really loud, you're surrounded by other people, maybe your end goal is just to dance, or maybe it's to get high and peak at some point during the night, or to have sex or whatever. Even though the moment is extended, there's direction within it, there's narrative. And that narrative doesn't necessarily conform to clock time, it's on its own timeline, but it does have peaks and valleys, it does begin and eventually end. Whereas what we're doing now, there's no end to it, it seems so yawning and empty. And obviously we can't be around other people, so all the sensory overload and the sensuality of the dance floor is drained out of the picture. It's interesting how it's even drained out of musical experiences that are happening.

I totally get that musicians have to do something to survive when they can't tour, because for so many musicians that's their only source of income, so playing Zoom shows makes sense, but I feel like it's such a different experience from an actual concert. Where you feel the vibrations from the speakers in your body, and you're near other people reacting at the same time. The lack of any sensory shift makes the moment impoverished, I think. It's so weird, I had that thought of, wow, this really shows how time is conditional. The fact that March took 400 years and April didn't really ... happen? It doesn't seem like April happened, there was no demarcation there. There's no narrative to it because everything is just bad all the time and slowly getting worse ... I thought that I would be fine through this, I kind of dug in my heels like, whatever, I'm in my house anyways so it doesn't really matter that I have to stay inside my house. But the psychological effect of everyone I know being stuck and suffering for it...

The idea that something bad is happening and there's nothing you can do about it except stay home is hard to swallow. All of that makes this hellish. But it's a good example, or at least an effective example [laughs], of how time is conditional. I wish I could be on a dance floor. Ever since I moved to Denver I haven't been to as many shows or dance nights as I once went to in Chicago, because I knew the environment, knew the layout of the city a little bit better. Here there's a lot of—I don't want to bad-talk Denver, but there's a lot of EDM and jam bands, just not as much of an abundance of stuff I like. But I didn't really miss it before all this, I was like, alright, that's fine, I'll get my few shows out, that scratches the itch as I'm getting older. And now I need to be in a shitty club with sticky floors and concrete walls, where I can't hear anything but feedback, with a bunch of drunk people [laughs]. That's something I miss that I didn't think I would miss.

Your book made me return to that Octo Octa album from last year [Resonant Body], where she gestures towards '90s rave anthems without just pastiching them or lapsing into melancholy. It feels like this intense solidarity.

Totally. She goes through those gestures with such a light touch, it feels like there's room for forward motion.

Right, it feels purposeful. And I feel like that's the challenge in a larger sense too, how to care for and remember all the people who are sick and dying.

It's strange to try to be present without being present right now. It's also troubling how conveniently dependent we are on internet technologies to communicate now and care for each other in whatever ways we can, like, with the refusal to bail out the postal service. Any non-corporate communication we have is being starved.

One of your recurring themes is how the gender expression of marginalized people gets eyed up and repackaged by capitalism. Have you read that Elijah Wald book, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock & Roll?

No, I haven't.

The title is very inflammatory [laughs], there's only, like, one chapter about the Beatles. It's more a secret history of American pop music, touching on some fantastically unfashionable artists like Pat Boone or Paul Whiteman, because people were listening to them. And one of his recurring themes is the way that music-making gets shaped by recording technology. He argues that a big influence behind the rise of the album in the '60s was—I'm not really an audiophile, I forget exactly what changed to allow for longer LPs, but something did. Before music was a recorded commodity, people would take songs and adapt them and put their own twist on them—it's a very human impulse, I think, to do that. But when the music industry comes along that becomes part of capitalism's repertoire. How do you feel that's all been accelerated and complicated by digital technology? I'm thinking of Arca sequencing her album to confound streaming services.

That whole phenomenon just has accelerated, right? As soon as something's published online it can be devoured. A somewhat recent example is Rihanna's Saturday Night Live performance [in 2012], where she or her creative design team borrowed elements from seapunk, which was this small semi-comedic vaporwave offshoot out of Chicago led by a trans girl and a cis girl, just making lots of '90s-nostalgic synth music. Lots of Ecco the Dolphin visuals. Lots of digital replications of paradises, beaches and oceans and palm trees, that made it into this Rihanna performance. Very quickly things from the fringes were scooped up and repackaged around a mainstream pop star. I think maybe what you're seeing is a new generation of artists kind of accepting that as inevitable? Making work so quickly that the swagger-jackers can't keep up.

You see a lot of trans artists in particular putting out a ton of stuff, like Black Dresses and Ada Rook and that whole network, releasing three or four albums a year sometimes. Pouring out music at the rate that they're making it, and not necessarily working through a label or thinking so much about marketing.

It's interesting because that's almost the speed at which the Beatles were releasing albums, back when an album didn't have to have these high levels of production, you could have four cover songs and it wasn't a big deal. You only have to write four to six songs, and then you record it all over two days. Before the album became this art object, when it was just a convenient package for songs by popular artists, you saw things happening a lot faster. Now that the internet is what it is, and has messed with many people's ability to make a living making music, you see that same rate for different reasons. I think most of the albums that I'm talking about are considered as full-length narratives, it's more about not needing a label to mediate between you and your listeners.

I love how you keep returning to that search for unlikely affinities. It's the "Crush With Eyeliner" thing, two people swerving towards each other while conspicuously failing at gender. Where are you finding those affinities these days?

In music?

Anywhere! It's the last question, it could be anything. That photo of Daniel Radcliffe walking all the dogs [laughs].

Oh boy. Honestly, the insane, powerful singing that my body used to do when I saw pictures of abject males has quieted a little bit since I got top surgery, so I don't explode in longing when I see a picture of Daniel Radcliffe looking at his phone while tied to 17 dogs quite the way I used to. I used to go to Twenty One Pilots a lot for that, because there's a lot of homoerotic play between the two of them. My fandom for them is like the adult version of my Savage Garden fandom ... any kind of beta-male affinity. You mentioned R.E.M., and I'm actually researching for a potential book about Michael Stipe, a false hagiography or critical biography, because I feel like he's going to write his own at some point, I can't do that for him. That seems illegal. But I want to write something about his place in culture from the position of a fan.

I feel like I'm also getting it in Britney Spears's communist reblogs. The idea that this person who was the one symbol of Y2K consumerism, everything wrong with the way capitalism has infiltrated music, is now like, "I was never a willing participant in my own exploitation." Her working against her own interpretation has been really productive, not in the erotic sense that you were asking about, but in the sense that she was held up as this image of perfection and now she's actively embracing her own failure ... I get a lot of vibrations just from seeing other trans people on the internet, seeing what we're all doing with ourselves in this weird time. The fact that people are looser with what they post, maybe, not necessarily in a lewd sense, just more casual. I wish I had a better answer to your question than Twenty One Pilots [laughs].

No, I love that answer!

It's one point where I feel like I have no agreement from the rest of music-critic Twitter, that this is a good band. But I also just festooned them with my transmasculine hopes and dreams, and now I can't get rid of them. They're a comfort band for sure. I used to watch a lot of their music videos compulsively, in the same way that I would with Savage Garden. "What if I had that body? Wouldn't that be cool?" What if I could look and move like that in this weird, failed rock stardom? Because that is a band that's all about pushing against the bombast of their alt-rock predecessors ... Imagine Dragons, Kings of Leon, those post-Arcade-Fire what if we ran away from this world together male survivalist fantasies of the post-apocalypse. And then Twenty One Pilots were like, what if we were dweebs in the post-apocalypse instead? What if we were just nervous, insecure, vaguely homoerotic bros in this world those alpha males are ruling?

I had never actually looked up a photo of Twenty One Pilots before. All their publicity shots look like they just got signed to an esports team.

Yeah, Tyler just stoops! He's got the muscles and the big black tattoos but he just looks like a sad little boy. It's such a contrast, and so relevant to my own interior experience of being a person.

So, if Elvis was a male bimbo, does that mean Savage Garden are catboys?

Yeah, they can be catboys! I like that. I was active on Savage Garden message boards and fanfic communities when I was, like, 12, and I feel like that was probably something that got written at some point. Darren Hayes got turned into a cat and fucking loves it.