It has been three months since the murder.

At the insistence of a shadowy tutor, the neglected ingénue Christine Daaé has been catapulted to stardom. Toggling between her and their (exhausted and exhausting) resident diva La Carlotta, the Opera Populaire has seen a period of quiet, comfortable success: a bustling box office and contented patrons, tepidly applauding familiar, easy repertory French farces such as Il Muto—works that feature but do not challenge their new star or the city’s bourgeois sensibilities. Three months of relief and of delight—no more ghosts, and no more notes.

And then the Phantom returns.

Crashing their New Year’s Eve masquerade in exquisitely bad taste, the Phantom delivers the manuscript for his new project: a feverish, frenzied adaptation of the story of a damned lothario, Don Juan Triumphant. The score, the hostage company discovers, is a cacophony of discordant, unpleasant wails and jangles; the enclosed sketches for its set design are a lugubrious nightmare; its projected “hero” is a sex pest who is finally swallowed by the Hell he has certainly earned in an end that no audience will ever mourn. Amid the Phantom’s tyrannical and absurdly sedulous demands (beefing with the orchestra’s struggling third trombone, body-shaming the chubby male lead), the cast reacts in horror. Ugly, unsingable, barely music or theatre at all, the tasteless Don Juan will certainly be laughed off the stage.

In a sequence added to the 2006 film adaptation by director Joel Schumacher, Miranda Richardson’s Madame Giry—the dance instructor who once saved the young Phantom and is, bizarrely, the only character in a film set in Paris who speaks with a French accent—breaks down in a hallway as our stalwart romantic lead Raoul (played by a staggeringly handsome Patrick Wilson) comforts her. She weeps for the young boy she saved: “He is a genius! An architect, a designer, a composer, a magician! A genius!”

“Yes, Madame Giry,” dim, sweet Raoul says soothingly, “but clearly genius has turned to madness.”

*

I turned thirteen in the summer of 1997—deeply closeted and, headed in the fall to an all-boys Catholic private school far from the suburbs, about to become more closeted still.

The key to surviving in the closet is plausible deniability. You frequently do not really need to pass; you just need to provide adequate cover, and signal a sufficient threshold of shame. The Nineties superhero comics that littered my bedroom—rife with rippling male physiques, full of gooey alien symbiotes menacing a half-naked Peter Parker, Superman’s clothes-shredding pietas, and the queer idylls of Charles Xavier’s welcoming school for the different—always had the optics of simple, normal, four-colour escapism, and so they survived a household that insisted by dizzying turns on suffocating religious devotion and paralyzing macho gruffness.

It was under these conditions that on my birthday—a teenager at last—my best friend and I went to the Cinema 8 in Pickering, Ontario, to see Batman & Robin.

From the opening shots, it was very clear something had gone horribly wrong; as the montage smash-cut from close-ups of male crotch to buttocks and back again, I felt, with a horrible sinking feeling, as plausible deniability seeped away like so much alien goo. I returned home that night with a feeling I’d never felt in a movie theatre and whose meaning I struggled to coordinate: I felt ashamed.

I slunk into the basement, using the dial-up modem on our ancient Hewlett-Packard (which I mostly used to play endless hours of multiplayer DOOM 2) to log onto AintitCoolNews. My cheeks still hot with confusion, I found the review I’d been scrupulously avoiding because of spoilers. I read Harry Knowles say this:

“First, let me say that Joel Schumacher should be shot and killed. I will pay a handsome bounty to the man (or woman) who delivers me the head of this Anti Christ.”

Over the next months, the film and its director rapidly became a punchline. In an episode of Batman the Animated Series, a lisping, mincing teen wrapped in a feather boa under a sign that says “Shoemaker” squeals with delight when he hears some other kids talking about Batman: “I love Batman! All those muscles, the tight rubber armor, and that flashy car—I heard it can drive up walls!” The other teens roll their eyes: “Yeah, sure, Joel.”

Knowles meanwhile spearheaded a blitzkrieg of frothing bad press for the film, himself penning 52 separate negative reviews riddled with his characteristic homophobia and misogyny (the paparazzi dubbed star Alicia Silverstone, whom they felt had been insufficiently sexualized in the role, “Fatgirl”), and it bombed egregiously with critics and fans alike, tanking not just the franchise but badly damaging the studio as a whole.

I may have felt ashamed, but the film hadn’t. And I learned a little more about what being unashamed can cost.

*

A fluffy, tufted gorilla suit makes its way clumsily through a crowd of oafish glitterati. It seems to be just part of the party’s awful, kitschy tiki-pastiche décor, but once the lumbering ape reaches the dais, with a sinuous, sensuous slink on the soundtrack, the beast begins to gyrate, and the crowd turns to stare. One glove slips off, then another, exposing elegant, manicured hands, and at last the fursuit falls away to reveal not just a woman, but the woman, blowing a kiss that leaves the striptease’s audience—onscreen and off—under her spell.

It is the showstopping cabaret number in Blonde Venus, the 1932 Cary Grant vehicle that introduced German émigré and bisexual icon Marlene Dietrich to American audiences. But it is also, shot for shot, the introduction of Batman & Robin’s villainous Poison Ivy—played by Uma Thurman, who oscillates wildly between a broad, aloof Mae West drawl and a mousy, twitchy academic, without ever clarifying which is the real and which the drag (Ivy twice disguises herself by pulling on a “wig” of Thurman’s own hair, while in the front seat her enormous goon Bane discreetly dons a chauffeur hat over his bio-mechanical luchador mask).

In her Notes on Camp, Susan Sontag credits one of the term’s earliest definitions to Isherwood’s The World in the Evening: “a swishy little boy with peroxided hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich”; in its Blonde Venus burlesque, then, and in the animated series’ cruel mockery of its director, Batman & Robin takes camp almost to its absolute taxonomic source. But Isherwood also there warns that camp cannot exist without a profound appreciation and close reading of its target: “You can't camp about something you don't take seriously. […] You're expressing what’s basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance. Baroque art is basically camp about religion. The ballet is camp about love.”

Joel Schumacher’s Batman & Robin (like Batman Forever, the film that preceded it) is a film in delirious love with its subject, and that subject is the goofy, gay beauty of the modern myth of the superhero. Overt in its desires and its delights, the film stares with incredible, lingering longing at Chris O’Donnell’s bedewed lips, submerges the cold, aloof Bruce Wayne beneath the warm, kind smirk of George Clooney (a Batman who smiles!), and—most unforgiveable of all—it put nipples on the bat-suit.

I will tell you the secret of why Batman’s nipples so enrage its critics: because the charade is over. The swells and dips of the lovingly sculpted male torso can be explained, and therefore explained away: these muscles are the site of masculine power; they speak, surely, of strength, of solidity and unremitting training. It is no accident that every femme fatale in Batman’s cinematic rogues gallery fans her hands across these rubberized zones, seeking the chink in the armor.

But the male nipple has no such function, no exculpatory capacity for war; the nipple is the site of weakness, of sensitivity—and of pleasure. Plausible deniability is gone. Put a nipple on the batsuit, and you admit to having fun.

Unproductive fun, perverse fun, queer fun—the Schumacher Batman films are, in Jonathan Goldberg’s analysis of a parallel vein in queer texts by Shakespeare and Marlowe, sodomitical, wholly uninterested in the patina of virtuous grimaces or generative reconstitutions of order (grim and grimy and gritty—the superhero equivalent of making love missionary-style through a bedsheet) and instead reveling in the spectacular and preposterous (a term that literally means “putting the ass first,” which is indeed both a Renaissance euphemism for gay sex and also literally how the films’ glorious butt-shots kick off their action).

It is not just this celebration of the beauty of the male form that marks Schumacher’s auteurism, but a wild, debauched excess of style and narratives that foreground the displaced, lost other. From Jim Carrey’s Riddler’s obsessive, yearning lust for Bruce Wayne to Chris O’Donnell’s martial arts laundry skills to a neon-noir Gotham City peopled by Day-Glo supermodel pompadour gangs, the films are wall-to-wall pageantry and faggotry, and they do not apologize for it.

Instead, they create a sensitively observed and minutely detailed love-letter to the wry surrealist goofiness of the 1966 Adam West/Burt Ward series that had saved the property from obscurity and catapulted Batman so immovably into pop celebrity, and itself made by a rogues gallery of Sixties counter-cultural icons. Indeed, Carrey’s zany hyperkinetics—clad in gorgeous crystal-studded leotards and with dazzlingly acrobatic cane-work—pay meticulous homage to Frank Gorshin’s own Riddler, whose giggling fiendishness nearly earned him an Emmy. “Remember,” Schumacher was fond of saying to the actors on set, “you’re in a cartoon!”

This style is not without its critics. Even on-set, Carrey struggled to connect with cackling co-villain Tommy Lee Jones; pleading to be liked, Carrey says he cornered Jones, who told him openly he detested the man—then, needled for more to go on, looked Carrey dead in the eye and rasped: “I cannot sanction your buffoonery.”

*

Schumacher’s broader oeuvre, even in films with budgets in the hundreds of millions, is consistently obsessed with the outsider, the misfit, the buffoon. His early endeavours include cult classic musical Sparkle (the prototype for Dreamgirls), followed by Car Wash—a film now infamous for queer icon Lindy, who responds to being called a “sorry-looking faggot” with an imperious “who’re you calling ‘sorry-looking’?” and rejoinders “I am more man than you’ll ever be, and more woman than you’ll ever get.”

In 1978, Schumacher penned the screenplay that took the quintessential American myth—The Wizard of Oz—and transformed into a critique of the American effacement of Black culture and labour: The Wiz. There, even the thoughtlessness of L. Frank Baum’s Scarecrow becomes a fable of systemic oppression, as the crows make the painfully sensitive dummy sing a song of their own devising about his own misfit uselessness that keeps him helpless upon his perch; when he doffs his hat to Dorothy, his head is not empty, but to her horror has been filled up by those who would keep him docile with “garbage.”

The critics that revile Schumacher ignore that he was perfectly capable of making tight, hardboiled films—the impossibly taut Phonebooth, the dismaying hopelessness of Falling Down—and instead just as often would, like Bartleby, prefer not to. The Lost Boys may be a shrewd glance at the AIDS crisis and at the rootlessness and poverty of so many young queer lives, but the film is also a roaringly energetic comedy that delights in chaos and cute moody boys and loud, rowdy found family. “Take off that earring; it doesn’t suit you at all,” the mean-spirited young brother hisses at the breathtakingly beautiful male lead Jason Patric (whose vampiric style now trends to the androgynous and whose resemblance to Jim Morrison is emphasized by a matching dissolve), then adds with a sneer: “Have you been watching too much Dynasty?” By film’s end, however, the two have made peace and forged an acceptance of Michael’s outré new alternative lifestyle: “You’re my brother, even if you are a vampire.” The malevolent father figure (played by Edward Hermann with the same avuncular dweebishness he brought to Gilmore Girls), however, who tries to reinstantiate the stability of heteronormative family, is quite thoroughly and satisfyingly exploded.

As an artist, Schumacher recognized there is something important, transformative, and transcendent about joy as resistance; he had as instinct what every poor NYC club kid knows: the revolution, when it comes, must be opulent.

He extended this interest in underdogs to fostering underseen talent, launched the careers of many of Hollywood’s best-known faces, shepherding the Brat Pack, Julia Roberts, Kiefer Sutherland, Colin Farrell, Gerard Butler, Matthew McConaughey, and many others into the public eye, frequently sacrificing established bankability to mint a new star. Pop singer Seal credits Schumacher with turning “Kiss from a Rose” from relative obscurity to karaoke staple, while Jim Carrey, whose buffoonery Schumacher had sanctioned not just in Forever but in Number 23, said that Schumacher “saw deeper things in me than most and he lived a wonderfully creative and heroic life. I am grateful to have had him as a friend.”

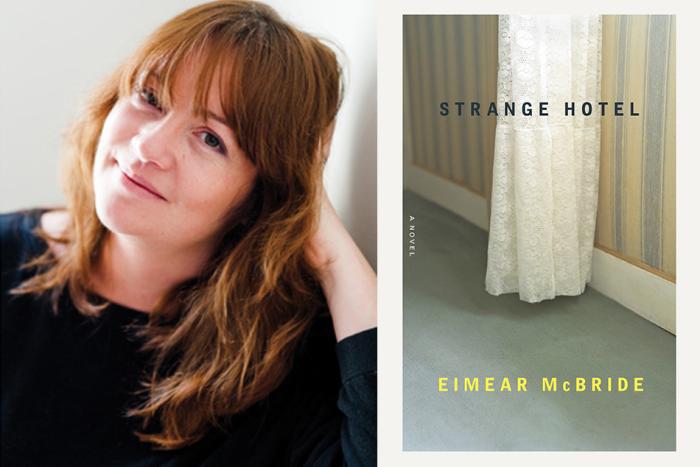

Remembering working with him on Phantom of the Opera (in which she plays the past-her-prime diva), Minnie Driver meanwhile recalled this week that “once, on set, an actress was complaining about me within earshot [about] how I was dreadfully over the top (I was).”

Driver said that Schumacher “barely looked up from his New York Times” and replied: “Oh honey, no one ever paid to see under the top.”

*

The climaxes of Don Juan Triumphant and Phantom of the Opera itself dovetail in a final number—“The Point of No Return,” in which the Phantom replaces the murdered lead actor Piangi as Don Juan (himself disguised, in the tissue of the play, as his own servant, Passerino, to effect a last cruel “seduction” before his damnation). The company knew if his opera was staged, he was certain to attend, and have laid traps for him—everywhere except onstage. Now they watch, helpless from the wings, as he stalks opposite the ingénue who consumes him, intent to abduct her at last.

The moment is badly, almost fatally, under-imagined in stage productions of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical, with the Phantom in a black shroud, completely illegible, and the stage half-heartedly dressed with a dinner table to facilitate a cheap disappearance trick at the end: a pretty melody, wasted.

In the film, however, Schumacher transforms it into a shocking, bizarre set-piece: the stage, ablaze with a hideously avant-garde depiction of the hell-mouth that has come to swallow Don Juan to his damnation. Surrounded by expressionist cut-outs of flame and jarring tilted-angle smash-cuts to sweaty flamenco dancers moving with jerky arrhythmia, the Phantom (here restyled as a beautiful baroque toreador) and Christine now climb up parallel winding staircases to Hell, as the score palpates and whirls with bleats and trumpeting and the theatre’s patrons recoil in visible confusion and disgust.

The coup de grace is the Phantom, whose disguise is no disguise at all: Gerard Butler’s own face, in a mere domino mask, only revealed in close-up at the last second of his unmasking to be part of an elaborate hair-and-makeup prosthesis to conceal his othering disfigurement.

His disguise ripped away—Passerino is not Don Juan is not Piangi is not the Phantom is not even the handsome “real” of Gerard Butler—he slices through a cord, plunging down the onstage shaft of Hell with his prize as, from above the crowd, the chandelier falls to crush the paper-fire set and consume the Opera Populaire and its screaming, tacky arriviste audience in gouts of burning wreckage.

This week we lost Joel Schumacher. He was a denizen of the NYC queer underground, a department store window-dresser, a fashion designer, a screenwriter, and finally one of cinema’s most iconic and reviled directors. He was eighty years old.

He left the audience disgusted, and the theatre aflame.