In her collection of essays Oh, Never Mind, Mary H.K. Choi summed up 2014 in three crucial lines: “The Internet has turned us all into pure energy. Doesn’t it feel rad? Send help.” Choi would know because she covers the internet (and more) on the internet (and in print) for publications like Wired, The New York Times Magazine, GQ, The Atlantic, and The Fader.

In 2016, she embedded herself in a group of teens for Wired and probed them on their online behaviour. It’s what ultimately led her to write her debut novel, Emergency Contact, where the internet cultivates a safe space for a burgeoning relationship. Barista Sam is insecure about his own poverty while college freshman Penny is simply awkward. “It’s the intimacy that comes from when you are unencumbered by your mouth-breathing meatsuit of awkwardness,” explains Choi. “The fact that they can just give each other their best, which is just asking good questions and receiving each other and holding space for what the other person is saying and processing it—that is such an act of service and selflessness and I think that is a beautiful aspect of the intimacy we can find in certain digital spaces.”

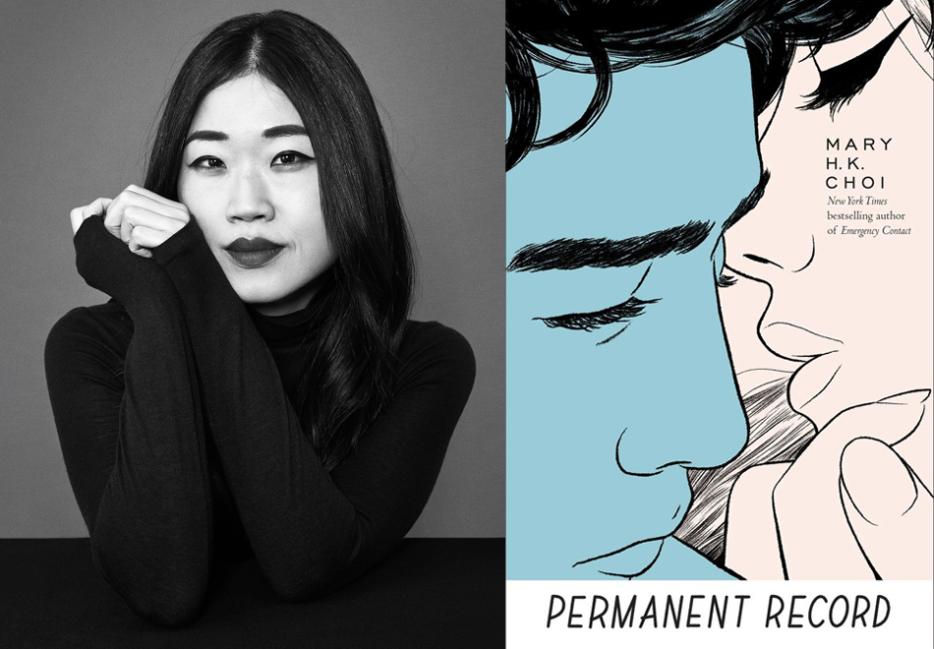

In 2019’s Permanent Record (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers), social media is less of a conversational buffer and more of a self-harm tool. College dropout Pablo Neruda Rind gets swept up in pop star Leanna Smart’s life so he can avoid his own debt and stasis. It’s a role reversal with a twist: a realistic Notting Hill with younger people who Choi says “eventually go back to their corners and finish cooking.”

I sat down with Choi in a hotel lobby that featured a Beauty and the Beast library, but with vases instead of books. We sat there, contemplating the objets d’art, New York and the gritty in-betweens of success.

Sara Black McCulloch: In Emergency Contact and Permanent Record, you focus on the families that we’re born into and the ones we get to choose. In a lot of ways, your characters are coming to terms with their parents being human but also the fact that their parents can’t always give them what they need as adults. You don’t see that particular approach to family dynamics often, especially in YA. Is this something you’re seeing in your own life?

Mary H.K. Choi: I think there are a couple of things. As the child of immigrants, there’s always a schism in terms of what you’re experiencing and what they have experienced. In my own life, we immigrated to Hong Kong when I was eleven months old. My parents were in their very early thirties, and there was this trapped-in-amber aspect to their childhood. When they left their mother country, they had this set reality that travelled with them and it didn’t age or evolve. Korea went from having the GDP of a small nation to now becoming a global power, and so there are a lot of things that have iteratively changed and become a lot more contemporary that my parents simply missed out on. Other than the fact that they have KaKaoTalk—the one texting app that all Koreans love—and the fact that now they can stream TV from Korea, they still have a lot of social mores that I think are trapped in amber and really speak to a bygone era. And so there’s been a lot of struggle with me living in a different civilization and growing up and them being trapped in this one thing. That particular gap can widen over the years.

Prior to getting older, it was about me having to rebel and feeling as though the way that I wanted to be was something that they could never possibly understand. It was really important to me, with Emergency Contact, that Penny’s mom Celeste wasn’t what you would typically see as the matriarchal figure in a lot of Asian pop culture, which is the tiger moms with all these expectations. So I really wanted to start off with a relationship that was a lot more like Lorelai and Rory Gilmore or, if not, then Edina and Saffy Monsoon, where it’s a role reversal, where the kid is always worried about the mother’s welfare instead of the other way around. It was also very important for me that Celeste be somewhat assimilated into American culture and so it wasn’t the cultural gap so much as it was just expectations, which is something that anyone can relate to.

With Pablo and his mother, I wanted to peel back the layers of what those expectations felt like—I mean that filial piety, fidelity and that first-born son expectation—and then just keep going with it. What we find in the second book is that a lot of those expectations come from fear. It’s a fear that is not only specific to East Asian or South Asian parents: you could ask any Haitian, Nigerian, Taiwanese, British parents—anyone! People want their kids to be successful and a lot of that lingua franca, that irrefutable co-sign, comes from name brand schools, vocations that pay very well and are universally respected.

Is there a risk of being too prescriptive, though?

As a person who is a little bit older writing for young people, I don’t want to be prescriptive in what I’m saying, but I do want to just allow for certain things to be the way they are without imbuing them with morality. For me, in my more recent years, it’s been about receiving my parents where they’re at and understanding that as grateful as we can be to our family of origin, it’s simply a repeated, cyclical trap of resentment to keep going to your family of origin for things that they don’t have. I’m in recovery and 12-step for different kinds of addiction and an eating disorder and there is this saying in meetings: “Don’t go to the hardware store for orange juice.” At a certain point, you know what your family of origin has a capacity for and to expect them to miraculously be different because you want them to be is just a recipe for prolonged and sustained heartbreak and suffering.

The only thing you can actually exert control over is your framing around that, and changing your own expectations. And that’s okay. It’s not rejection and it doesn’t have to be. It’s this wild and contrary act of acceptance. I think that’s the only point that growth, mutual appreciation and understanding of each other’s humanity can actually come from.

It’s hard being a parent, too. Everyone has intergenerational trauma. It’s not something that’s wholly new to us as a generation just because we have all these social media outlets where we can complain or even have the language for it. My mother knew famine as a child during the Japanese occupation of Korea. It’s a very real thing: that fear comes from personal experience and actual testimony. I can’t fault her for that. If anything, it’s an invitation for me to experience compassion and to know that there’s so much about my parents that I won’t ever know. It goes both ways and I think that there’s so much reparenting that has to happen on both sides.

Has that approach to compassion altered the way you now engage with other people?

Totally. We’re all so broken! And it’s really beautiful. Anytime anyone has been particularly vindictive or contemptuous towards me, I recognize that what I’m witnessing is a tantrum and sure, the shrapnel is getting on me, but what I’m witnessing is someone else’s pain and that doesn’t mean I have to stick around for it or experience a co-dependency with their happiness, but it is not something I can then use as artillery either. It’s not something I even have to hold onto! It’s been a really beautiful reminder that whatever interaction I’m having with someone else, their rendition of it isn’t something I’m going to wholly understand and I have to be okay with that.

Do you find that with career prospects, too? Or even with writing, which is not an easy thing to do.

Oh my god, it’s so hard. Now that I’m a quote-unquote author (or scare quotes, rather), I talk to so many other writers and we’re constantly so shell-shocked that we’ve signed onto this vocation where we have homework for the rest of our lives. And there’s nothing more existentially harrowing than having to produce on a daily basis. Also, fiction is wild: So let me get this straight, you’re just sitting there, making shit up? What is that about? It’s so subjective and human—this compulsion to create art.

There’s also another facet—selling yourself as a writer—that’s weird, too. I’m thinking of that piece that was published recently, about the journalist being an influencer. How do you mitigate that role and the expectations that come with it?

I think about this a lot because when I’m trying to straddle those two perspectives, I get in a lot of trouble. There is nothing more stultifying, in terms of being able to create, than that. Nothing hogties me more than writing while I’m editing while reading while receiving while thinking about the audience. I liken it very inelegantly to the fact that you just can’t poop and eat at the same time. Anytime I sit in my own audience and anytime I’m worried about how someone will receive this based on the merit of my previous work, that is when I cannot write anything with value. I can’t write and aim at the same time. If you’re aiming, you’re aiming for a lot of different targets—for any made-up version of a reviewer or an audience member that you’re imagining. I can’t think of anything more scattershot! I can only write for me, and I know that people say that so much and it sounds like such a stereotypical bromide but I can only move in one direction and so I may as well move in the direction that feels clear to me. Otherwise that’s a guessing game! It’s hard enough to listen to my own intuition versus sitting here, making up what I think other people’s expectations will be.

There’s also this idea (or ideal) of objectivity in journalism, which often extends into writing. I think it’s a lofty goal, but it’s ultimately impossible. Is it that people just don’t want to acknowledge their own biases?

It’s so impossible! We should also surrender that completely. It’s so interesting because New Journalism, the long tail of it, went from writing in the first person, to interjecting your point of view, doing write-arounds and talking about people contextually and not just what they’re saying and wearing or—god forbid you only have forty minutes for a cover story—what they’re eating. It’s always going to be distorted by you having been there. And I think that if everybody just accepts that, it’s a good baseline. And then other people, having enough integrity, can just not make facts up. That would be great in this day and age!

The thing about biases is that largely we don’t know that we have them and that’s not good or bad, it just is what it is. I think it’s compounded with this notion, too, of how we presume social media is straight from the horse’s mouth. I think that can be really confusing because everything is a performance and so everyone, on any day, for every mood and filter should be taken with a grain of salt.

In Permanent Record, Pablo really gets caught in the “best life” aspects of Instagram. Yet, he completely overlooks the fact that he has this incredible lifeline: the people who are looking out for him. I mean, both his friends and his parents align in their observations about him.

It’s funny because if you were to ask your best friend, “Do I isolate? Am I selfish? Am I grandiose?” Your friend would tell you, “Oh yeah, 100%.” But you have to ask them point blank. It takes a lot for those people to say that to you because it’s so obvious to them that it never occurs to them to tell you that you are these things. Anytime I feel hysterical about someone saying something to me—like if I get that jolt of contempt and I’m filled with moral outrage and righteous indignation—generally, I find that that stuff is accurate. We’re not a cipher! The people who know us, know us. That’s the you. It’s the difference between your recorded voice and the voice you hear. No one thinks their recorded voice sounds better! Like, you think you’re out here shining, and your friends are like “No, you’re doing this weird thing, a weird squirrely dance that you’re trying to hide.”

What was it like analyzing male friendships from that perspective?

When I was in edits for this it was during #MeToo and Cosby and all I wanted was to write a tender, sweet and true-hearted boy. I wanted to write emo, loving demonstrative friends because that’s what I’ve actually seen in New York by dint of all of us being squished together with very finite resources. My male friends have the most beautiful, supportive and edifying conversations with each other. They really hold each other up and it’s fucking beautiful. I thought that was a particular dynamic that just didn’t get enough attention at all.

I also think that in New York, you need to be surrounded by a group of people who will support you because you will need them. I’m a writer in New York. I have needed my friends. I have sometimes needed them financially. My colleagues, my friends, my cronies have supported me during very lean times. I survived 2008 and 2009 in media in New York. I will always be grateful to them for that because it takes a village and if I shine, then you shine. You take turns supporting each other. You take turns reparenting each other. And that’s just part of it. And being happy for someone in the way that you would sometimes hope your parents would be but can’t and so you have people celebrating you with deep, deep love and understanding of what it took to accomplish something. I mean, they put up with your ass in the lead up to this shit! So you bet they will celebrate you.

It’s the in-betweens we often overlook. They get left out of those success narratives too. Permanent Record analyzes the Western ideals of success, ambition and straightforward career trajectories. Pablo keeps watching these Secret-like Youtube videos, and yet he can never connect to them. As he starts changing and accepting his own shortcomings, he finally encounters success narratives that resonate with him. Why was it important for you to include that in the book?

The thing that the supercut doesn’t show you on Youtube, as the person makes their millions or gets their free ride to Columbia or whatever, is all the disgusting actual work that had to take place. When you’re starting out, your output is repulsive. Ira Glass has that great quote about how your output never matches your taste for a long time and that’s a really important thing to hear because Permanent Record comes from this notion, this data that follows you in terms of your successes and your failings: your FICA score and your credit and all this stuff. It’s also this notion of permanent record, which is the reality distortion of social media, where you feel so much pressure that you feel like you cannot afford to make mistakes.

We love the story of the beauty blogger who made billions, or the one about the person disrupting hotels or the child disrupting the salad industry, or Forbes’ 30 Under 30. Now, it’s all about getting a Ted Talk before you’re out of middle school. The bloodsport has gotten so aggressive that it’s sort of laughable. That narrative—jinned by the 24-hour news cycle and the pyrotechnics that we need for every viral hit— really does a disservice to the countless majority of people who just grind. The other thing is that I wanted Pablo to have uncertainty around his own career but also acknowledge that there are a lot of people who are successful doing things that you won’t hear about on your local news channel. I think that there’s a lot of grace in that. And acknowledging that as a path that can lead to happiness is important.

Pablo’s dad, Bilal, talks about the notion of autotelism, the act of doing it and the satisfaction in doing it. It’s not about the accomplishment, it’s about the very slow and grueling work of just getting better at something over time. It always takes time. It’s fine to want and it’s fine to try, but the second you try it and it doesn’t work, please try working a lot!

Bilal also talks about how the root of all creativity is abundance: wanting what you already have.

How ephemeral is getting what you want? I’ve gotten so much in my life and it’s so amazing how quickly it turns to resentment or this voraciousness, that will never be sated, for the next thing.

When your first book did very well, like New York Times Best Seller-well, did that make you nervous or even resentful of your own success?

Oh, it completely fucked me up so hard. What happened with the first one was that I had written it and rewritten it and it sat in a drawer for eight months because my agent didn’t like it. A different agent reached out saying they were a big fan and asked if I would ever write a book. I told him I already did and he asked to read it. He read it and had notes, so I tackled the notes. And then he told me he could sell it and it went to auction and it did really well. But what happened with that is that because I had zero expectation that the book would ever sell, I had another job on camera for HBO’s VICE and I was just on a different wave during that time.

Emergency Contact had sold, but before it came out, I had written a draft of Permanent Record. I told myself, if the book tanks, I’m never going to be able to write again and I have this idea for another book so I’ve got to write it now. While I was shielded for the first draft, I didn’t know that promoting a book would be all-consuming and just emotionally expensive. It didn’t make the NY Times best-seller list the first week out, it made the list on the second week, which very rarely happens, and then stayed there for a month.

During that time, I was rewriting Permanent Record and that was the most...I mean if you want to talk about scattershot, I didn’t know what I was doing. There were so many edits where I just rewrote the whole thing and then could not accept changes because what I had written was just nonsense and I didn’t know what it was and I got further away from it. I was more out to sea and that was a really big lesson. I told myself it was just the sophomore thing, because I don’t know how to write a book. I’ve only done it once before, like, who the fuck am I to say that I can write a book? I won the lotto once.

It wasn’t until I got away from all that that I realized what I had done and how much my final actual draft resembled my first early draft. I realized how you could get burned out without producing anything.

There were so many honest conversations about money, credit and debt and the insanity that is having an 18-year-old figure out the rest of their lives and place a huge bet on that decision (with an insane loan). I mean, we’re all so scared to talk about money and we avoid it altogether because my god, that pressure!

And a loan of that size! I mean, you really do mortgage your entire future and it’s like you’re betting on a level of financial solvency by a certain age so that you can recoup on this initial investment and pay people back because, as the clock is ticking, all of these loans are metastasizing. And I really wanted to talk about that. It’s great if you get into Columbia, Duke, and NYU, but how are you going to pay for any of it? How do you enter the workforce in this day and age with that much volatility—with a house strapped to your back? Why don’t you own a house for how much you owe? And then graduate school: do you really want to pursue that or is it an issue of sunk cost where you need to do that extra thing because you haven’t questioned what you wanted to do, and now it’s a question of what you can do to get the money back doing what you’re doing? How will you ever know what you want in your quietest self? How will you ever find your due North if you’re completely saddled by this clock and this money?

It leaves you with little room to fuck up, no?

You can’t afford to! And if you fuck up you better not tell anybody and you better hide it and again, even if people find out, you better play it off and tell everyone that you’ve got it figured out. And you best hope that watching the right Youtube video will help you figure it out because I don’t know how else you would.

There is a great divide and there is so much otherizing and fetishizing that happens with each generation as technology changes at a rapid pace. It was, first, about otherizing Millennials—and it’s not the reductive aspect of it, it’s the difference that you’re creating. And with that comes a great breakdown in communication and apprenticeship. You have people who are in such a scarcity mentality about these people taking all the jobs, so they keep all their institutional knowledge to themselves, and the new people coming have no idea how to deal with that hostility, but they also don’t want to fuck up and so they don’t ask any questions.

You now have so many people who have a very specific skill set, and that’s wonderful, but they don’t know how to do fundamental things like ask a question, make a mistake, remedy it and call attention to it in the right way. The result is that everyone is now like “Don’t trust Gen Y,” and Gen Y is saying that you can’t trust Gen X-ers. It’s this incredible communication breakdown that breaks my heart and as a person who is older talking to younger people, I just want everyone to hang on, and not go to AskJeeves to figure out how to write a cover letter! Ask someone and admit to that vulnerability and have that person help you out. I think a lot of that responsibility falls on our shoulders because we don’t make it easy to ask us things and that’s fucked up. It would just be so much better if everyone talked to each other.

The food in Permanent Record, especially those snack combinations, really brings everyone together, and showcases their resourcefulness. It also facilitates some difficult conversations. How was it writing about that?

It was really beautiful. I wrote a New York Times Magazine article about candy a while ago and it was really short and joyful but that was really triggering. And I realized I was definitely a sugar addict. It’s that recursive nature of disordered thinking. When I’m in that mode of thinking, it’s all I can think about and it was really interesting. I had enough awareness to be like “Holy shit, you’re catching a weird ass contact high.”

With this, I knew that food was going to be a big part of it because of Pablo’s mixed race. It’s the one arena in which he doesn’t feel like an impostor, where he doesn’t feel tested, where he doesn’t feel like it’s a pop quiz he’s going to fail. Even if Pablo were at church or at a wedding or around his parents’ friends, he might feel uncomfortable, or might feel as though they’re about to give him a pop quiz about how much of his culture he can actually be familiar with. He doesn’t have that with food. It’s his love language, the way he shows up for people in his life and he doesn’t ever worry about the cultural authenticity of it. And I wanted him to have freedom in some arena.

With my own personal history around it, it was a really beautiful thing where I could experience joy around food again and where food was appropriate in my life: you could be excited about it and be happy about it and feel abundance in it, but you don’t have to be drunk on it. And it doesn’t have to be the only thing that you think about. The way I knew I had an eating disorder, even though for years I thought I didn’t qualify as a bulimic anymore, was that someone told me that if you believe that being a different size will change everything about your life, you probably have an eating disorder. And that blew my mind because I thought I didn’t have an eating disorder but I was alternately paleo, or vegan or on some crazy regimen or not eating this or orthorexic or whatever, but thought it was a coastal elite thing or whatever. Now, I know that was really disordered. Now, you eat a meal and you forget about it—that’s what life is actually like. You have life in between meals. It’s not eating something and trying to figure out ways to game it or get rid of it for the next six hours.

It was also really important, like an amends to myself or a healing practice, I think, to create a character in Leanna where she’s like ostentatiously famous, where her body is so renowned and admired and gawked at, and she doesn’t have an eating disorder. It makes me weepy to think about a young woman who is that scrutinized who chooses to feed her body and chooses to nourish it lovingly and have an appreciation for what her body is capable of doing. Just the idea of having a woman like that felt like such wild subversion and that was really beautiful for me as someone who is older to just write a love letter to a person like that. I think that that helped me do a lot of forgiveness around all this abuse and turmoil I put my body through and the dissociation and just how I left my body in different places in my life.

Leanna, as a mega pop star, is the source of a lot of body anxiety and dysmorphia for other people, but she isn’t absorbed in it at all.

Absolutely. She just doesn’t take that on. Leanna is fucking awesome in so many ways. She’s hugely flawed and she’s very young. Someone even told me that I vilify her and I really don’t. I don’t think there’s a single smart woman in this world who has even a modicum of ambition who wouldn’t understand exactly why she does the things that she does. This famous person is surrounded by this cacophony, this overwhelming din. It’s the age and the level of celebrity that we have to grapple with. This is a person, as far as you know and think, but the celebrity industrial complex is a great many other external forces and people. She is the head of her personal brand: she is the CEO, CFO, COO, but also there are people she is answerable to and that’s a real part of her life.

But Leanna is also quite whitewashed as a pop star.

I really wanted to talk about that. I remember when I interviewed Rihanna for one of her first cover stories for Complex (when Good Girl Gone Bad came out). She had just cut her hair and people were figuring out that Rihanna was stylish. And she told me that she was really excited to have a little bit more autonomy in her career. I asked her what she meant by that and she said that she was singing in her actual accent. I think that there is this coming of age that happens twice when you are not of the majority. You have your coming of age just like in life: your Saturn Return or whatever. And then you have this coming of age where you realize that you have inherited this double consciousness, like what your contribution is as an artist of colour. I certainly had the same thing. And I’m so grateful that I started writing when I was older because I could work all that out and figure out where I was at with it and then produce from there.

With Leanna, she gets really excited when the industry changes enough that she’s finally in a position where she can have a Spanish-language release. That was something she felt she had to earn. I wanted that to be an issue, even for her and for how powerful she is: if she’s coming through that Disney entertainment factory (we’ll use that as an example), then what does that mean and how does that affect how people receive her? And then what she can claim for herself later?

The centre of gravity for this book, and the source of food and cravings, is the bodega — it’s where everything begins and reconnects. Pablo’s job is a service job and it’s a low-valued job, and it requires a lot of expertise that’s often overlooked. Why was that crucial to you?

I didn’t want this to be a dissertation on or contemplation of city living where we don’t know each other and the death of intimacy. It’s more like that New York thing where we’re all crammed in together and you end up gleaning the weirdest parts of each other. And I love the bodega because it’s the place I missed the most when I briefly lived in California for work. I just wanted a bodega! I didn’t want to get in my car to go to Target for Advil! I just wanted the two-pack to swallow dry on the train! But the bodega is a 24-hour way station for a lot of different types of addiction.

There are witnesses to your personal crises.

All under those horrible lights!

And those cameras!

It’s just like Russian Doll! That’s the nexus. We’re all glitches in each other’s Matrices. And then there’s that fucking judgmental bodega cat.

As much as we think that technology is creating a rift, there are still these little things we have to do that force us to interact with each other.

Reluctantly! That’s a really beautiful part of New York: you’re forced into those situations. Like mass transit: the fact that we have to mutually tolerate this broken railway system is just hilarious to me. It’s the source of so much drama and strife and the bodega is definitely another touchpoint where we just all have to put up with each other. We all have to get in that fucking line and god forbid you have to go in the morning and everyone before you is ordering an egg sandwich because you’re going to be there for 37 minutes.

With your work, how do you reconcile something that you love bringing you closer to the thing you hate (overworking, capitalism, burnout)?

It’s really hard but it’s a scarcity mentality. It’s also something I can speak to from a place of great privilege. I have never been in a position where I had to spend an advance cheque on life. I’ve always had jobs in between the creative moments. I’ve always had a job, feathered the nest, and then did all speculative weird stuff. I keep the pragmatism with those jobs and I keep the high-risk stuff high risk. I also don’t worry about money insofar as I never do something for money because that’s always gotten me in trouble. I call it that Tahiti test: if this thing went away to Tahiti, is there a part of you that would have some regret? Or are you relieved? And if I’m relieved, then I’m not allowed to do it. If I’m regretful over some aspect of it, then I have to sit there and contemplate it. I never send things to Tahiti when it’s just money-based and if I don’t experience true relief. I’ve never done anything solely for money because it’s just too emotionally expensive that way. I’ll do stuff for money that I’m interested in or that I find entertaining or do it because I can’t believe that people can be paid to do it. Doing something expressly for money has only ever made me resentful, has taken three to four times longer than I think it will and has only ever brought me just butt-hurtness. It’s only ever tarnished the work that I do. I just don’t want to be embarrassed about anything that I make and that threshold is low—I mean, I survived being a writer.