On a spring night in Madrid in 2003, the Spanish photographer Paco Gómez got a call from his brother-in-law. He had seen a messy pile of discarded photos on Calle Pez, a street in the gentrifying neighborhood of Malasaña, close to where Gómez lived. His brother-in-law thought it was the kind of thing that would interest him. He was right: Gómez put on his shoes and hustled out the door of his apartment.

The impulse that sent Gómez into the street and sweating toward Calle Pez was less professional than personal. Gómez was from a mountain town in the province of Avila, the child of a working-class family. Unlike most people he knew, his parents had hardly any photos of his ancestors. As he grew up, this absence of a visual family history left a void, and had the added effect of making the lives of others appear more interesting than his own. The first person in his family to go to college, Gómez’s vicarious nature—or budding voyeurism—found an outlet after he moved to Madrid to study engineering and worked as a night garbageman. During his shifts, as families slept and college students less encumbered than him partied past dawn, he hung on to the back of his crew’s truck, looking into the vehicle’s belly and scrutinizing its contents. “I learned to recognize what had occurred in a home by the kind of junk the people threw out,” he recalled. “A breakup, a death, an eviction.” He came to feel that trash obeyed certain universal laws, creating decipherable patterns. When he turned from engineering to photography after college, he didn’t develop a particular style so much as an MO: studying details in old pictures to excavate clues, as if searching for his family’s own vanished past. Yet he had never seen anything quite like the cache of photos he found on Calle Pez in front of a dilapidated apartment building.

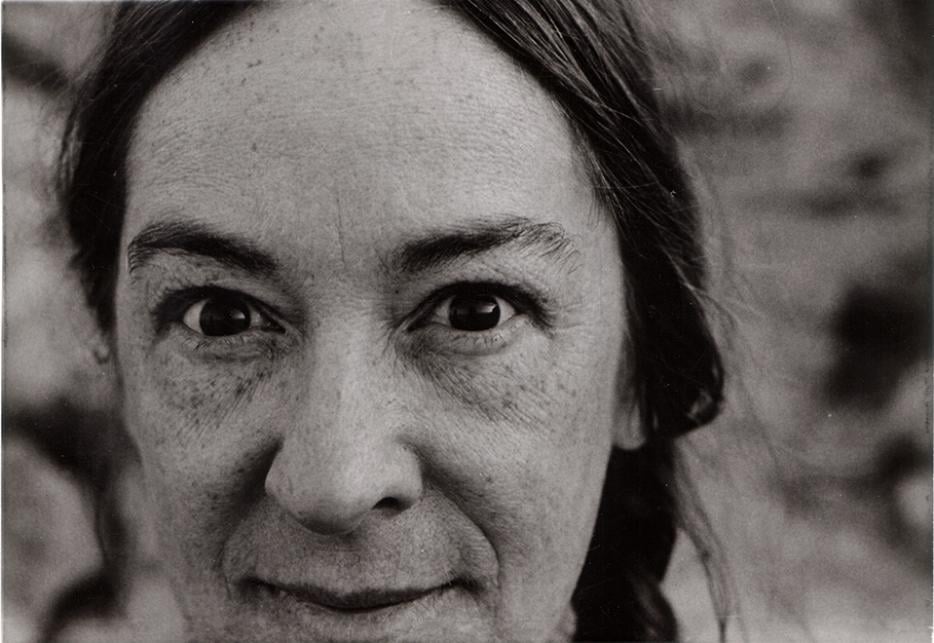

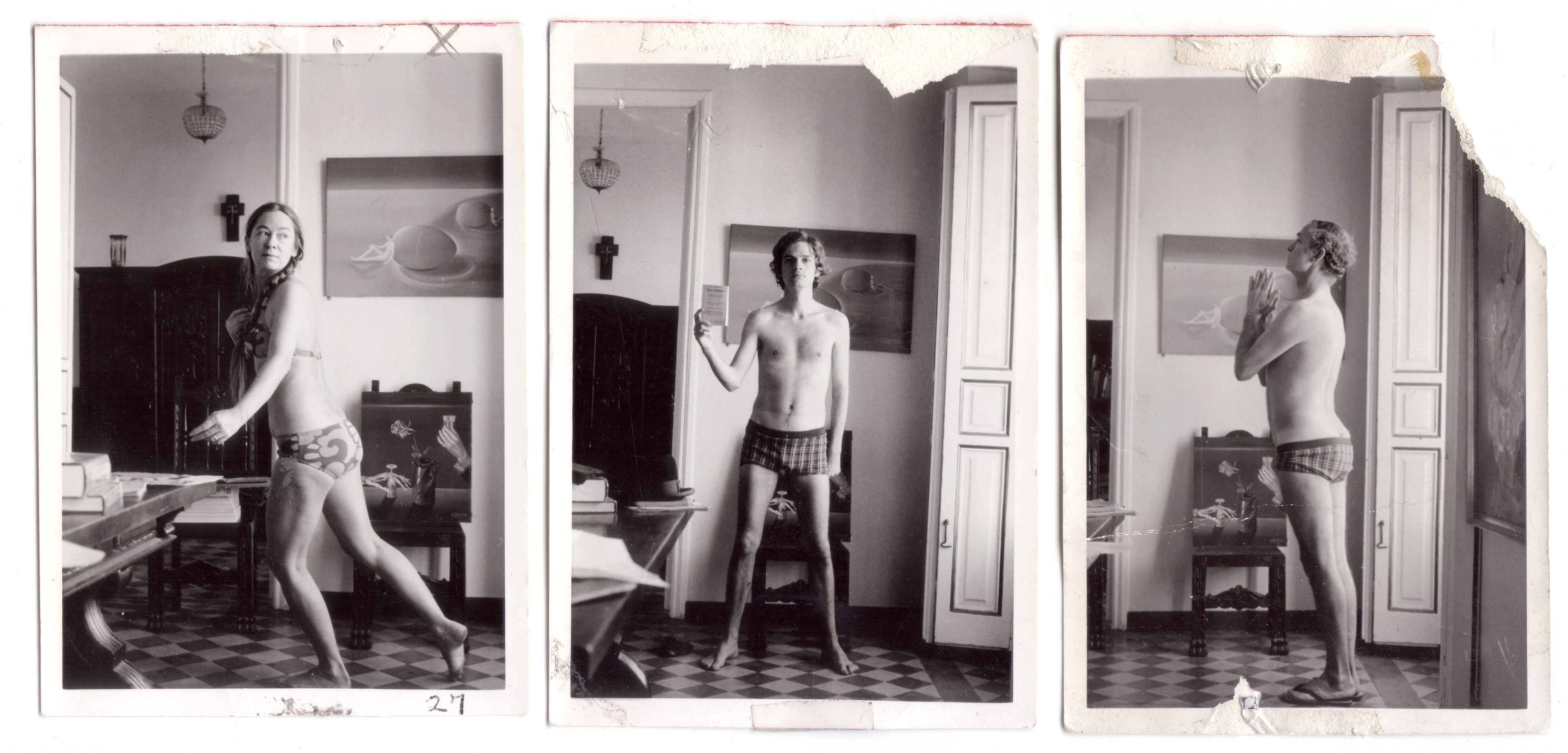

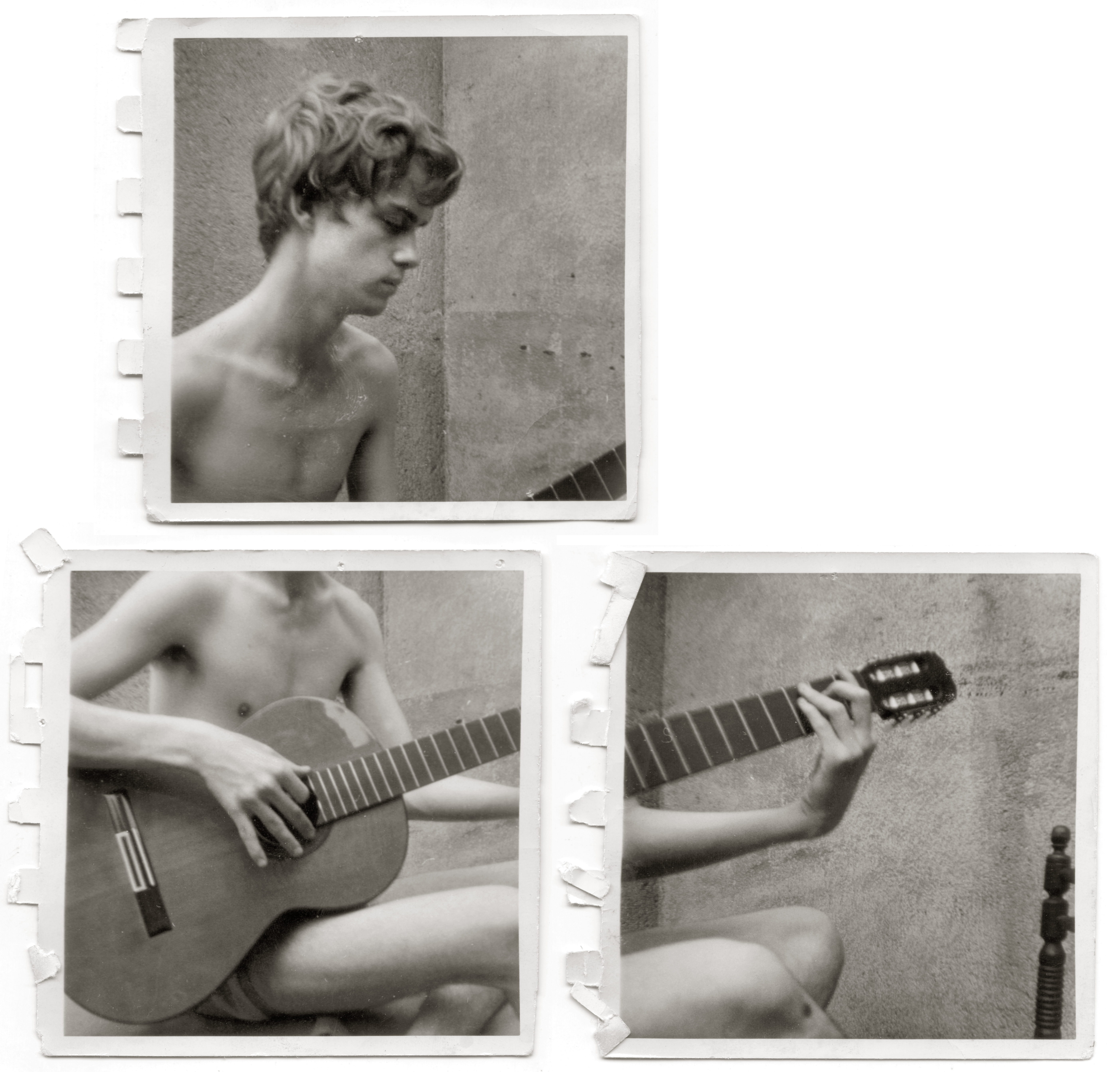

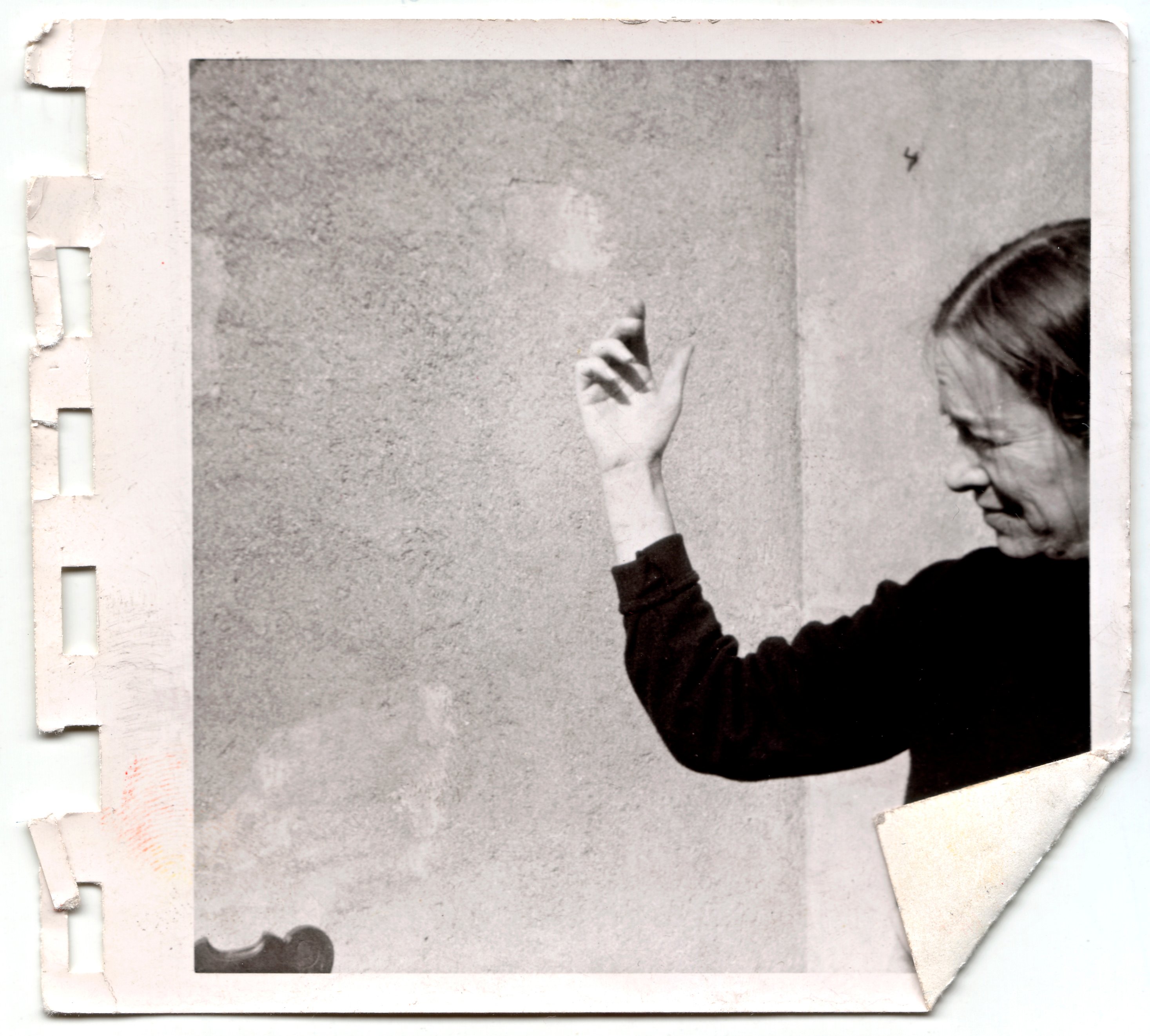

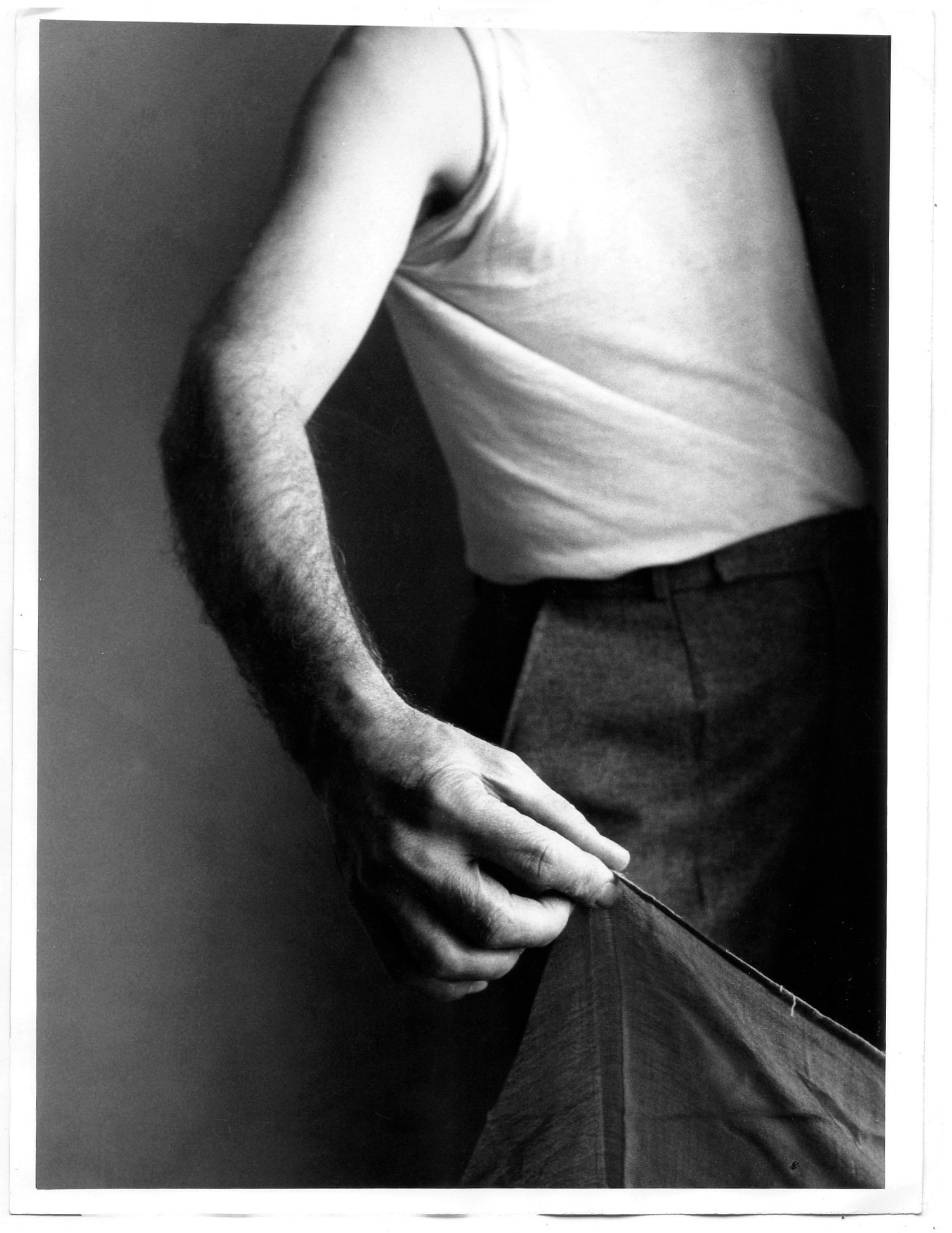

The photos contained something much stranger than mere unknown lives for Gómez to imagine his way into. In one, a man in ratty underwear stood in a bare room in a posture of crucifixion. In another, a statuesque teenage boy posed like a magazine heartthrob. In still another a woman with a lustrous ponytail stood before a Dalí-esque canvas of angels and demons. The exhibitionist fervor of scene after scene of otherworldly gazes and unnatural postures struck Gómez as very un-Spanish, never mind the fact that the pictures had ended up not destroyed, but out in the street like this, a private life turned inside-out. Who the hell were these people?

He had little time to dwell on the strange images. The heap of discarded photos had attracted other magpies like himself. He scrambled to collect as many as possible.

Though he didn’t yet know it, Paco Goméz had just met the Modlins.

At one in the morning on June 3, 1950, a young man and woman stepped off a Greyhound at the bus station in downtown Los Angeles. Married the previous August in North Carolina, he was twenty-five and she was twenty-three. He was handsome, with fine-boned features and expressive eyebrows. Nearly his height, she had long legs, a wide yet subdued smile, and a bouncy wave of brown hair. She exuded an enigmatic, impenetrable air. They had met in college acting opposite each other in a play. They connected through their shared faith in two redemptive forces: Jesus and art. Their names were Margaret (née Marley) and Elmer Modlin.

More than actors—he was also a poet; she was a painter above all else—the two were dreamers who longed for “a divine state in creativity,” as Margaret put it. Like countless others before them, they had arrived in LA, according to a future newspaper article about them, “with their hearts full of hope.”

Their wallets, however, were empty. They landed in LA with a mere twenty dollars, fifteen of which went straight to securing an apartment in Hollywood. The two ate mainly potatoes as they got settled. “One day we have chicken to eat,” Elmer said, “and the other thirty days we have feathers.” He and Margaret had the tolerance for precarity of the young, and blind faith that the future would accommodate their hopes. And most important, they had each other, along with a pact: whoever got the first big break, that person’s career would take precedence over the other’s. Whether or not they meant for this agreement to last a lifetime, it would.

Margaret got the first break: a scholarship to Otis College of Art and Design. She began the degree, which took her five years to complete, in 1953. By then, she was a mother. On February 19, 1952, she had given birth to their only child: Nelson Modlin. She was smitten with her baby, yet art remained her higher calling. Elmer hadn’t booked any TV or film roles, so he worked three jobs. When Margaret graduated in 1958—after experimenting with every “‘ism’ extant,” as she wrote—she destroyed nearly everything she had produced. She entered a discouraging “Dostoevskian Siberia” period in her art and got a teaching job.

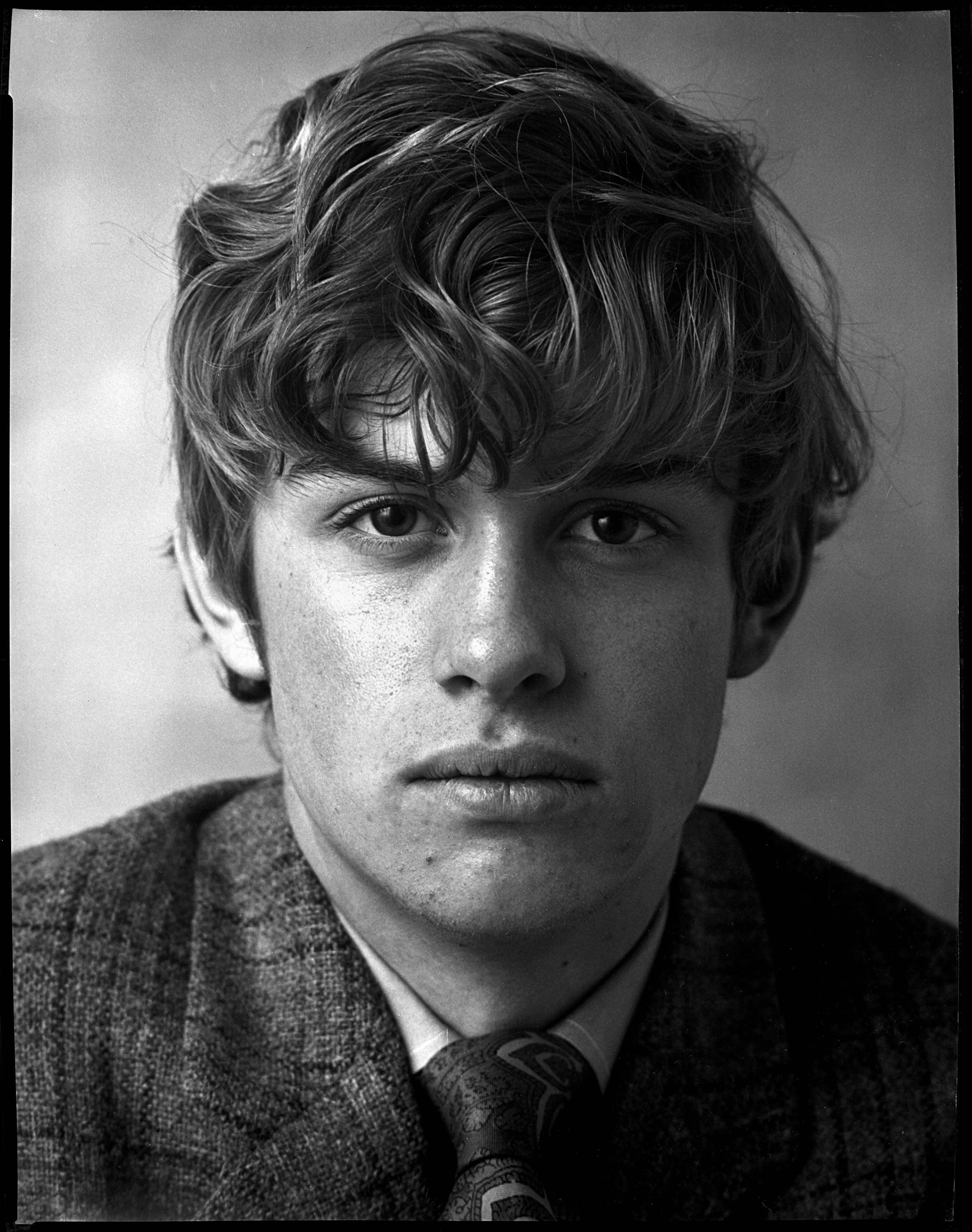

A decade passed. By 1968, Elmer, now forty-three, had landed a handful of bit parts, including an uncredited, non-speaking role in the background of the final scene of Rosemary’s Baby. It seemed he and Margaret had been relegated by central casting to roles as extras in life and art. Nelson, who was now sixteen and looked like a Greek statue, would later tell his second wife that during his childhood his parents sometimes drank to excess and took their anger out on him.

By the loose standards of Los Angeles in the 1960s, theirs wasn’t the strangest household—though it was still strange. Margaret, for instance, painted a nude portrait of Nelson holding a flute when he was eleven, and he would pose as a model for the construction of her imagined universe into adulthood. He held deep admiration for his mother, bragging to his friends that Margaret was an artistic genius. When Nelson reached his teens, Elmer and Margaret enrolled him in the acting track at Hollywood Professional School, an arts high school that only had morning classes so students could go audition in the afternoons; alumni included John Drew Barrymore and Judy Garland.

The family might have continued on in their middling Hollywood trajectory, unremarkable victims of the American mirage of fame, if it hadn’t been for a famous American who came into their lives. Or rather, one whose life they nudged themselves into: Henry Miller.

One of Elmer’s jobs was working at a trendy vegetarian restaurant. There he had met Miller, a regular, and gotten to know the legendary author of transgressive autofictions such as Tropic of Cancer, who was now in his late seventies. In early 1969, after meeting Miller herself at an art gallery, Margaret had a vision involving him and a recurring dreamscape—Doric columns with drapery fluttering gauzily until a temple-like structure collapsed into the sea—which had been visiting her at night since childhood. “There suddenly came to my mind,” Margaret remembered, “an image of Henry Miller with wings seated in the haunting landscape of my dream. I knew that I must paint him.”

Paint him she did. Miller gamely agreed to pose, sitting for Margaret that spring before heading to Paris for the filming of Joseph Strick’s adaptation of Tropic of Cancer. They reconvened in December and during their sessions Margaret reveled in her conversations with Miller, who extemporized on subjects such as Christ, the Bible, and Francis of Assisi. She saw the saint as an antecedent to the writer who was lending her his greatness. “Miller’s lifework has the singular effect of letting the pus out of the wound of conscience of modern man,” she wrote, “and of cauterizing it with the fires of the Apocalypse.” Considering that Tropic of Cancer had been banned in the US until the Supreme Court overturned previous obscenity rulings in 1964, Margaret’s reading of Miller’s work was a curious one for a devout southern Christian, and revealing as to her views on the purpose of art.

Where others saw rottenness, Margaret saw a call to holiness. She painted Miller seated with angelic wings and a notebook in which he recorded “everything on earth,” as she conceived it. He gazed at the viewer as Margaret’s dream extended behind him, a harp partially composed of a woman’s head with billowing brown hair set in the middle ground. After finishing the laborious painting, which she believed had turned her at last into a true artist, she gave it the title Henry Miller Ve Más Que Un Aguila, Henry Miller Sees More than an Eagle.

Why had she chosen a title in Spanish? Because she loved the sound of the language, and for a few years now she and Elmer had been fantasizing about Spain as a new home for the family, a sanctuary where art and God were still intertwined in the popular imagination, and a place far from American upheavals such as the 1965 Watts riots, which they feared presaged total social breakdown in the US. Spending time with Miller, who had lived in Europe and who Margaret and Elmer idolized to the point of fanaticism, pushed them to actually go to Spain. They blamed their lack of recognition in the US on its shallow, materialistic culture. In contrast, they believed that Spain, home to several of history’s greatest painters, was great because of its Christianity. That it was ruled by a murderous Christian dictator, Francisco Franco, wasn’t a deterrent. Another of its draws was the fact that several prominent Hollywood producers were making large-scale films in Spain.

Before Margaret had even finished her portrait, Nelson was telling friends at school that his family was moving to a country he cast as a promised land for aspiring actors. He was popular, striking classmates as both cool and dignified, and they were awed by his boldness, surely most of all by the fact that he was going alone to Madrid in the fall, to attend an English-language high school while setting up a home for him and his parents, who would follow in the spring. So it went: in September 1969, seventeen-year-old Nelson flew to Spain. Elmer came in May, accompanying their belongings and Margaret’s artwork on a freighter across the Atlantic. Margaret, meanwhile, packed up the rest of their things in LA and wistfully found a new owner for their Siamese cat. Then she flew to Madrid.

The Modlins would never again live in the US.

Courtesy of the Modlin Estate and the Malvin Gallery.

Gómez kept the photos he had found on Calle Pez in the tiny darkroom he had set up in his apartment. He and his wife had their first child, then soon after, he landed a job working for a prominent photographer, which required him to travel frequently. It was only when his family moved to a new apartment in 2004 that he rediscovered the mysterious photos.

Poring over the many shots of a middle-aged man and woman and a youth who was presumably their son, he once again wondered who these people were, and what the purpose of the photos was. They were bizarre to the point of unsettling. They often posed with props and bent postures, as if twisted, Gómez thought, “by a kind of divinity that, from heaven, sought their breaking point.”

He wracked his brain searching for a working theory of who the family might be, to no avail. If they were diplomats, as he briefly speculated, they would have lived near the foreign embassies, not in Malasaña, and it was doubtful their belongings would have ended up in the street. “It was an indecipherable mosaic,” he thought.

That March, Gómez was at a friend’s apartment working on a photography project. After taking posed pictures of his friend, he noticed a frame on the wall with four photos of the same enigmatic, dark-haired woman—the woman in the photos from Calle Pez. His friend explained the frame was a gift from someone who, it turned out, had foraged alongside Gómez the night his brother-in-law had called him with the tip. And now his friend told him that the woman was a painter named Margaret. Gómez went straight home and searched online.

He found a June 2004 article in the newspaper El País. The reporter wrote: “A building in the center of Madrid in a state of ruin, with the roof held up by construction supports, the stairs of eaten-away wood and mailboxes full of letters that no one claims, holds a secret. The American artist Margaret Marley Modlin died in 1998, leaving in the apartment, where she resided the last thirty years of her life, a collection of more than 120 paintings of a surrealist style that she had painted. Her only child Nelson died in 2002 and her husband, Elmer, last year. In Spain there are no other relatives. The valuable paintings remain in the dwelling, orphans, without an owner, in a building that could be demolished at any time.”

Margaret and Elmer had spent their honeymoon on Roanoke Island in the Outer Banks. They arrived after nightfall as a storm blew in. It took down the power lines in the quaint town where they were staying, and the next day gathered into a hurricane. Outside their hotel, waves pummeled the beach in a thunderous percussion and the wind lashed every surface. Feeling invincible, the newlyweds went outside. Margaret cupped water and threw it over Elmer’s head, christening him, “El, God of the Sea!” He baptized her back, calling her, “Margaret, Pearl of the Sea!” This scene would come to be a creation myth of their marriage, and Margaret would later claim that the hurricane descended on them, yet suddenly all became calm in the eye of the storm. This was surely entirely false, though their sense of heightened togetherness was not. “We embraced,” Margaret wrote breathlessly, “and the elements embraced us, and God embraced the elements, thereby embracing us. This was our mystical beginning.”

It was fitting, then, that settling in Spain also came with aquatic symbolism. After a brief stint in another apartment, the family moved into the one on Calle Pez—Fish Street. To reach their new life all three had crossed the same baptismal ocean of Margaret and Elmer’s honeymoon, and now, indeed, they were fish out of water. Neither parent would ever learn to speak Spanish well, splashing around insouciantly in the foreign vitality of Madrid. They loved the bustling cafes, the boisterous street life, and the bullfights (where they spied on Salvador Dalí with binoculars). It was all perfect in Margaret and Elmer’s eyes, as was the apartment, with its large, north-facing windows through which pigeon feathers drifted along with ideal painting light. And, of course, they frequented El Prado Museum, home to works by Goya, El Greco, and Velázquez, which made it easy to romanticize Spain as “a paradise for the hungry soul of the artist,” as Margaret wrote.

Meanwhile, Nelson was beginning to break away from his parents. When he made landfall in Madrid the previous year, he had conquered his new international high school. The best friend he met there, Jim Lipton, recalled nearly fifty years later, “He sort of arrived with a bang. He ran for student council, made friends very quickly, became popular.” Lipton remembered that Nelson was put off by his father’s insistent actorliness, his need to be “on.” In spite of his own theatrical training—or perhaps by employing it—he began refashioning himself in opposition to his parents. He was very sensitive to art, and many of the women he would go on to date would be artist-types sprung from the mold of his mother—Margaret hated most of them—but he developed a matter-of-fact, businessman-like persona. “He was in a sense a very conflicted guy,” Lipton said. “Nelson never talked about his parents, except to say that his mother was a genius and someday the world would recognize it.”

To coax this fame into being, Margaret got to work, pursuing her art with a singular intensity. Sometimes she didn’t leave the apartment for days on end. Meanwhile, Elmer took auditions and Nelson started college in Salamanca, occasionally coming to visit on the weekend with friends. His draft number had come up high, so it didn’t look like he would have to choose to either go to Vietnam or dodge.

The Modlins eased into their new life. They remained sure that soon—very soon—fame would find them.

Gómez was determined to uncover the secrets hiding on Calle Pez. Eating breakfast at the Malasaña dive he went to every morning, he asked the bartender if she knew the Modlins. Her grinning answer: Of course she did! She suggested Gómez talk to another bartender who knew them better, and to a woman who lived next door. He thanked her, finished breakfast, and went to work, his mind churning with thoughts about the family.

The woman who lived next door to his breakfast spot was a dressmaker who still recalled Margaret’s measurements, as well as anecdotes about the family; for example, that Elmer often bristled at noisy neighbors disturbing the peace of his wife’s work and once went out to the balcony with a trumpet that he blared to bother them back. She told them how in love Margaret and Elmer seemed. She also showed Gómez a lithograph of a very strange painting of… Henry Miller? He was stunned when she explained that the Modlins had known the famous American writer.

A cascade of serendipities combined with Gómez’s tenacious detective work accelerated the pace at which more revelations came. Like a re-creation of Antonioni’s Blowup, Gómez scrutinized a picture of Elmer standing on a street, though he wasn’t sure which street… until he ended up eating at a restaurant right there. He visited nearby storefronts and came across an art restorer who had known the Modlins, who directed them to a man named Carlos Postigo, Margaret’s former art dealer. Postigo was happy to talk to Gómez and told him about the penurious life Elmer and Margaret led in service to her art. Although her paintings were out of sync with the trends of the art market, she asked for astronomical prices that guaranteed they wouldn’t sell. Postigo didn’t know where the canvasses were now but thought it would be a shame if they were lost. Dying to see Margaret’s work, Gómez contacted a man that El País had mentioned in its brief article about the Modlins, with a name as quixotic as the quest to know the Modlins: Miguel Cervantes.

Cervantes knew Elmer’s sister, who still lived back in North Carolina. After Margaret’s death in 1998, Elmer’s deep grief gradually widened into dementia, so his sister had asked Cervantes to help manage her brother’s affairs. He spent a great deal of time with Elmer during the last year of his life, listening to his stories in the Calle Pez apartment, which nearly overflowed with Margaret’s work. Cervantes related to Gómez a history of the Modlins that didn’t seem to square (for instance, that McCarthyism had forced them to leave the US, and that Elmer had been a famous soap opera actor), though the way it didn’t square somehow did square with the outlandish, myth-laden narrative of the family Gómez was coming to know. After Elmer’s death in 2002, Cervantes became the executor of the Modlins’ estate. Gómez asked: Could I see Margaret’s paintings?

In the fall of the same year that Margaret and Elmer began their life in Spain, another American arrived in Madrid: President Richard Nixon.

On October 3, 1970, Nixon and Franco rode through the city in a motorcade and Margaret went out to see them pass, along with over a million Spaniards. As the open-top Rolls Royce with Franco and Nixon drove by, surrounded by cavalry, her world contracted. “The only sound was that of the horses’ hooves on the pavement, the polite applause of the crowed, and my own wild heartbeat,” Margaret wrote. Much like Paco Gómez when he first learned of Margaret’s identity, she rushed home. She had just beheld a true soldier of God, and since for her aesthetic and spiritual experience were one and the same, back at the apartment she sketched Franco’s dark eyes, which she was sure had met hers as he passed. She felt a burning need to paint him, the same as she had done with Henry Miller.

Over the next three years, Margaret attended every public appearance by Franco that she could make it to, each time bringing home more of his essence to commit to canvas. By the fall of 1973, she had completed her portrait: Generalísimo Franco, “Tú que vives al abrigo del Alitísimo, y habitas a la sombra del Omnipotente,” whose translation is roughly, “You who live sheltered by the Highest One, and dwell in the shadow of the Omnipotent One.” She and Elmer both spoke of the pre-Civil Rights area in the United States in Edenic terms, a time of less turmoil, and through the lens of their privileges transplanted to Spain they similarly saw the order and calm of Franco’s dominion exclusively in relation to the benefits of oppression, not its costs and pain. A high-placed Spanish lawyer was so moved by her portrait of the dictator—who she had painted alongside a symbolic lion and lamb—that he vowed to use his relationship with Luis Carrero Blanco, the prime minister and Franco’s right hand, to ensure it ended up hung in a palace. Margaret was ecstatic. In December, however, this plan unraveled when the Basque terrorist group ETA assassinated Carrero Blanco with a car bomb. The lawyer wrote Margaret a regretful letter.

As always, Margaret and Elmer persisted. Five years later, in 1978, she at last secured the opportunity she had been working towards her whole career: a solo show of her work. It would be held in the gallery of the Circulo de Bellas Artes, a celebrated arts venue in the center of Madrid. On display would be thirty-nine oil paintings and eighteen silverpoint drawings. “I have fulfilled my dream,” Margaret wrote to her family.

The opening, on October 2, was by many measures a success. Henry Miller contributed a piece on Margaret’s art; her two sisters who she hadn’t seen in twenty-five years came; a swath of the Madrid culturati turned out in force; and reviews of the show were positive, a few even over-the-top in their praise. Yet in spite of this reception, her work didn’t sell, and more critically for an artist so comfortable with poverty but so uncomfortable with anonymity, word of Margaret’s artwork didn’t spread beyond the conservative publications that applauded it.

Although she and Elmer couldn’t see it, this was only natural. Abstract expressionism, minimalism, and pop art had long since redrawn the landscape of the art world, and land art, performance, and conceptual art had likewise transformed visual expression. And yet there Margaret was, dedicated to an atavistic surrealism with renaissance-style religious themes, seemingly unaware that not only had art moved on aesthetically, but so had Spain politically. Franco had died in the fall of 1975, a sorrowful event for Margaret and Elmer, and the newly formed Spanish congress would ratify a democratic constitution two months after her opening. Two years later, in 1980, an unknown director named Pedró Almodóvar would release his first film, spitting in the space of traditional values and aesthetics, and soon La Movida, a wild and explosive countercultural movement of music and art, would take over Madrid. Margaret had left her home in the US for a country she felt spoke to her soul, but that country had changed.

She and Elmer would spend the next two decades in their Calle Pez apartment, drowning in rising waters of obscurity as he acted and Margaret painted as monomaniacally as ever, neither ever ceasing to believe in her greatness. They maintained that all their dreams had come true in Spain. And in a sense, they would come true thanks to a person as single-minded as Margaret, a person who, like the Modlins, longed for an extraordinary story: Paco Gómez.

When Gómez finally beheld Margaret’s paintings, he felt deflated. While he had fantasized about apocalyptic masterpieces of the greatest unknown painter of her time, as he stood in the storage facility in the outskirts of Madrid where Miguel Cervantes had taken him, he saw something else—derivative Dalí, esoterically insistent symbolism, and idiosyncrasy that was just eyebrow-raising rather than transporting. The paintings shone with technical virtuosity, sure, but it was hard to see their value beyond the strictly biographical.

But, seeing the paintings, Gómez finally understood the cache of photos that had set him off on this strange journey. “I discovered that the photos were representations of the characters that lived inside the apocalyptic imagination of Margaret and that she used as the models to compose her canvasses,” he wrote. “It was so evident that it had never even occurred to me.” Elmer, Margaret, and Nelson weren’t in a cult or practitioners of disturbing private rites. They had simply been posing for her paintings.

After seeing Margaret’s work, Gómez continued pursuing the Modlins with renewed urgency. He pestered the Catholic organization that owned their building until it let him go inside. There, amid the melancholy abandonment, he found three blue notebooks, professionally bound and with title pages: Elmer and Margaret’s personal writings and copies of letters. The mysteries of the Modlins broke open once and for all.

The secrets of the family were all there: their lives in the US, their relationship with Henry Miller, their years in Spain. And on a second visit to the house, Gómez found another document, one that seemed to explain Elmer’s colossal dedication to Margaret’s art and an art-filled life: a description of his experience as a young soldier as one of the first people to arrive in Nagasaki after the US dropped a nuclear bomb on the city. Amid the ruined landscape, full of dead bodies and traumatized survivors, he saw the worst of what humanity could do, and it had scarred him. Why wouldn’t he dedicate the rest of his life to art and beauty? It wasn’t the agreement the young couple had made on arriving in Los Angeles in 1950 about who got the first break. It was Elmer’s need for art to redeem life, as he believed his wife’s work did.

By now, the Modlins’ artistic universe had bled into Gómez’s own. He had begun using people as models to recreate the Modlins’ photos, posing them in the same places and postures as if this could bridge the passage of time that separated him from the family. He even tracked down a family that had posed for Margaret long ago; they were happy to pose for Gómez, recalling how Margaret’s artistic world had briefly and magically transformed their own. Meanwhile, he also learned the details of Margaret’s death—a heart attack at age seventy—and Elmer’s subsequent physical and emotional decline. But one last mystery remained: Nelson. He had died between his mother and his father in 2002 at the premature age of fifty. What had happened to him?

Once again, Gómez’s investigative tenacity quickly produced results. On a tip from Miguel Cervantes, he located Nelson’s best friend, Jim Lipton, who still lived in Madrid. Gómez interviewed him and learned about Nelson’s life: his exasperation with his parents, his workaholism with his own audio business in the radio and film industry as an adult, his generosity as a person, his three wives. Shortly before his death he had found great peace, buying a small rural property in Brihuega, northwest of Madrid. Gómez was able to speak with his second wife, Berta, who shared warm memories of Nelson. His obsession with work had driven them apart and they separated around the time of Margaret’s death, only to speak again the month before his death—a heart attack at home in his apartment. Nelson had loved and been loved and left countless friends bereft.

It was the spring of 2007 now, four years since Gómez had first seen the Modlins in the photos he had scavenged, and he felt that his odyssey was nearing its end. He had uncovered more about them then he ever could have imagined, and the wonder it had filled him with likewise had exceeded all of his expectations. It was time to share the buried story he had uncovered, so he published a few articles, and then El País’s weekend magazine did a feature to coincide with a full-circle event Gómez had put together: a show of Margaret’s work at a Madrid gallery.

The opening was on a Thursday and the gallery was full. Gómez’s friends were there, as well as people from the Modlin universe that he now knew, and also people he had never seen before. Amid the clamor of the show, Gómez found a moment to enjoy this apotheosis of sorts, the merging of his life and the Modlins. Now that he saw the paintings hung in a gallery, they looked changed to him, even remade. “Margaret’s paintings seemed like different ones,” he recalled, “they were still strange, but had their own life and character.” She was no longer trapped in forgetting, and he was no longer a lone obsessive like she had been. Margaret and Elmer and Nelson weren’t suddenly famous, but the Modlins were no longer ghosts in a north-facing Malasaña apartment. Their story had escaped out into the Spanish city where they had lived for some thirty years.

Paco Gómez would go on to self-publish a book with photos about the Modlins, which would lead to more discoveries about the family crowd-sourced by passionate readers—everything from footage of them visiting Franco lying in state to clips of Elmer in forgotten films. It was as if an ocean of memories had been floating in space, just waiting for “divine creativity” to piece them into a cohesive composition. Gómez felt he had completed a work they had left unfinished. But the Modlin family’s most poetic role was in Gómez’s own household, where his kids looked at photos of them in the living room and talked about them as if they were relatives.

Soon after the gallery show of Margaret’s work in Madrid, Gómez was walking on Calle Pez and noticed a white sticker on the callbox of the Modlins’ building. He went to have a look. It said: The Modlins lived here. Remember them.