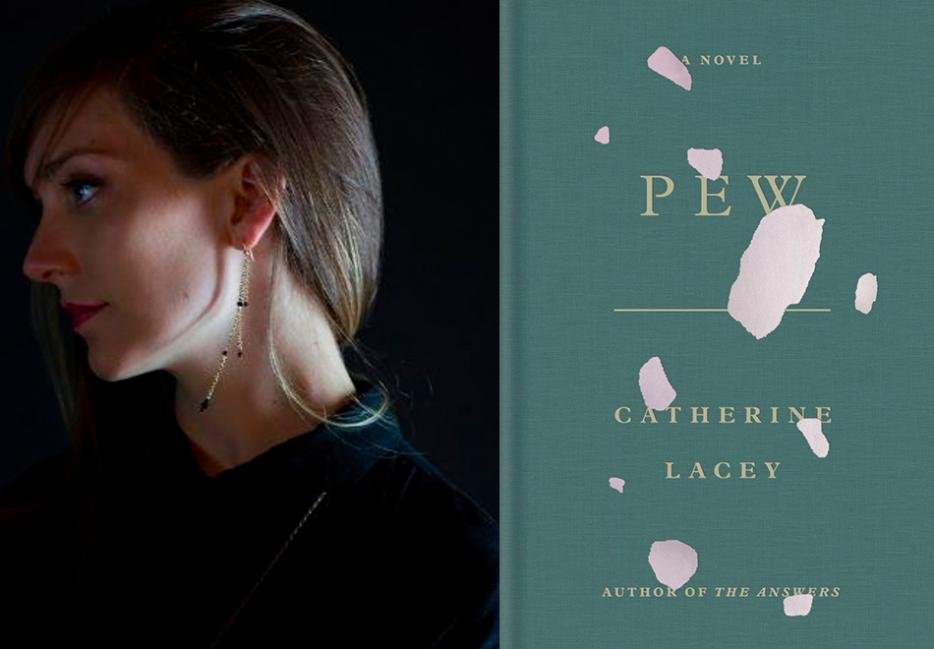

If there’s one thing that rivals the discomfort of small talk, it’s an awkward pause. It’s a lull that either leads to conversational filler or oversharing. People really risk it all instead of being quiet, which is why that uncomfortable silence is exploited by HR people, priests, and journalists alike. In Catherine Lacey’s third novel, Pew (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), the titular character and novel’s namesake already complicates conversations because they have no identity: their ethnicity and gender are described as indeterminate and confusing. They have no memory or backstory. But it’s Pew’s silence that seems to rattle others most; instead of fixating on Pew’s origins, they project onto Pew, and confess their secrets and their sins.

Pew could be post-body, beyond human even, but in a conservative and religious town in the American South, they are interpreted as an uncooperative patient, stranger danger, an archangel, and more ominously, a sacrifice. These communities are founded on conformity, where the right answers to a line of inquiry lead to acceptance and assimilation. It takes only a week for Pew’s muteness to rattle their foundation and saviour complex.

Over email, I talked to Lacey about the origins of Pew and, more importantly, if a novel and its characters can originate in a body or somewhere else.

Sara Black McCulloch: You had a very religious upbringing in Mississippi, and I wanted to know how that influenced writing Pew, especially when it comes to shedding identities? Did this start with a voice or something else?

Catherine Lacey: The person at the center of Pew is an impossibility—a person without qualities, a person whose appearance is changeable, impossible to define. I think to some degree the desire to inhabit the sort of simultaneous visibility and invisibility that such a body would give a person would appeal to most people, regardless of their background.

As a child, I took to religion with a kind of seriousness that made childhood strange, or rather it revealed that American hypocrisy of being a country founded on Christian systems of morality while also claiming to be secular. As a kid who took the Bible very seriously, I was understandably frustrated that moral goodness had no currency at school, in fact it was a hazard. But eventually the Bible came to feel inadequate, full of its own paradoxes and cruelties, so perhaps the book was an attempt to create a kind of annihilated space in my hometown, my home-area-of-the-country.

Pew is also not someone who is shifting between identities because they don’t have one, which frustrates people to the point that there is a breakdown in communication. I read in your interview with the Paris Review that you think a lot about the body and posture—how they influence the rhythm and voice in sentences when you’re writing. To Pew, the body is where so much dysfunction and other bad things start. Did that approach to writing change when you were writing the character?

On a purely creative, personal level, the book was an attempt to argue with myself over that point. Does the book have to be in the body? Does the voice necessarily come from a body? I truly am not interested in setting parameters or concerns for myself that remain fixed. I want to argue with everything I’ve ever thought.

The only time Pew really does speak to someone, it’s with Nelson, who warns Pew not to say anything because the community will only hear what they want to hear and twist their words. There’s a pressure for Pew to assimilate as Nelson did, but there needs to be a trauma narrative first. I wanted to know what you thought about trauma narratives and the ideal victim. Does Pew’s silence threaten this community because it challenges their saviour complex?

This phrase, “ideal victim,” is scarily apt. In the last several years, partially from the way the internet provides such an easy confession chamber, the act of sharing a traumatic story has become so common that doing so—personal, public exposure—has, at times, felt requisite. Of course, some people don’t have the option to expose or not expose a personal story, so I’m not talking about that. But I feel strongly that one shouldn’t be required to expose personal trauma to be seen as worthy of equal treatment, or justified in their anger over an injustice.

In some ways, this is the way American society has instinctively responded to the increased opportunity for telling trauma narratives. Essentially, trauma is treated like capital, and you must spend it in order to increase the value of your position. I felt this particularly around the time #MeToo first became a thing. I did not want to describe personal experiences in order to participate, but at certain times it felt like that was the price of admission—even when some tried to say it wasn’t required. It seems to me that many BIPOC Americans may often feel this way, that there’s a heightened value being placed on sharing the details of times that your life has been denigrated and if you’re not willing to share that then you have less of a right to complain, to have a voice. Of course, there’s no centralized authority in society that is setting that pattern—it’s emerging from us collectively, which makes it the kind of problem that fiction is best suited to deal with.

I was not directly thinking of any of this as I wrote Pew, but looking back I can see how this concern slips in. They’re not willing or not able or simply not sharing what has happened to them, so the system is breaking down. Nelson didn’t have the option to suffer privately and he resents it. He resents the community around him relishing in their personal experiences of “doing the right thing,” because he recognizes it as the same kind of noxious righteousness that leads people to commit violence in the name of their government or religion or hate group or whatever. Righteousness is so dangerous. It erases nuance.

Many people fill in for Pew’s silence and start revealing more about themselves. What they confess to Pew is, at times, much darker and honest than what comes up at the Forgiveness Festival [in the novel]. This made me think about performative public apologies. In a way, when someone asks for forgiveness like that, they seem to be asking people to forget about their harmful actions rather than asking for help or learning from them. Even at the Forgiveness Festival, everyone’s eyes are closed, so the apology never reaches the person it’s intended for. What does forgiveness mean or look like to you? Is it about being good or bad, a fear of God, or just someone understanding how to be in the world?

There’s this Protestant concept of being wiped clean, of being redeemed through private confession to God. As a child I was so interested in Catholic confession, in the booth with the priest—we did all of our confession silently, alone. Maybe Protestants repress their shame and guilt more than Catholics do? I would absolutely read that psychological study.

I do think there is an increased societal preoccupation with forgiveness right now in the culture and maybe that’s part of the reason I wrote this book now rather than years ago. Perhaps the most useful thing I learned from Christianity—but perhaps even more from my mom than from church—was that there is no point in holding a grudge, that you’re usually better off forgiving someone rather than carrying around anger for them. But it’s also odd to me that I find it easier to forgive individuals than collectives. I remain pissed off about Mississippi’s general hypocritical disregard for the poor and the suffering while they all claim to be Christian but I’m fully ready to forgive individuals for individual things. I don’t think that’s necessarily the best way to be, but that’s what I’m working with these days.

The epigraph is from Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” and while I know the reviews of Pew have focused on the unnamed narrator and the summer festival at the end, it also centers on the idea of the scapegoat. I wanted to talk about Pew’s role in the Forgiveness Festival because while they won’t identify themselves, the community abandons them at the end, rendering Pew an outcast full of the town’s confessions and sins. Pew is the scapegoat.

I hadn’t thought about the story that way but I think it's a valid and interesting take. There’s this idea in Christianity that all people are born broken and sinful, that faith in Jesus makes a person whole. So, in a sense, by sending Pew to this festival, the question is being raised of, what would Pew have to confess to if they were human, but without history? What is the nature of that original brokenness? The question of innate sinfulness is fascinating to me. What does it really mean to be born incomplete and what is this state of completion people supposedly are striving to reach?

While Pew is a narrator with no identity, they do ask us, in a way, to make a choice: do we go along with conventions, or do we abandon them so we can change and grow? This question is especially prescient right now, at a time when we’re being forced to reconsider our relationships to power, money, and each other. Have you been reevaluating your own relationship to and participation in any of these now?

Oh, absolutely. I think it’s difficult to accurately or honestly describe how “the now” is changing me, but I think the process of writing Pew helped me defamiliarize myself with my own body and by doing that I see other people’s bodies differently and I suppose that’s all I want reading the book to do. I hope it made me a slightly less shitty, slightly more kind person in the world. I think there are many ways to read the book, to be frustrated by it, enjoy it, to not enjoy it, but the only stance in the reader that I am willing to say is a failure on their part is wanting to know “what” the person at the centre of Pew is. It wasn’t a secret I wanted to keep; it’s the problem I’m asking the reader to approach. And there’s no answer to the problem, or at least I don’t claim to have it.