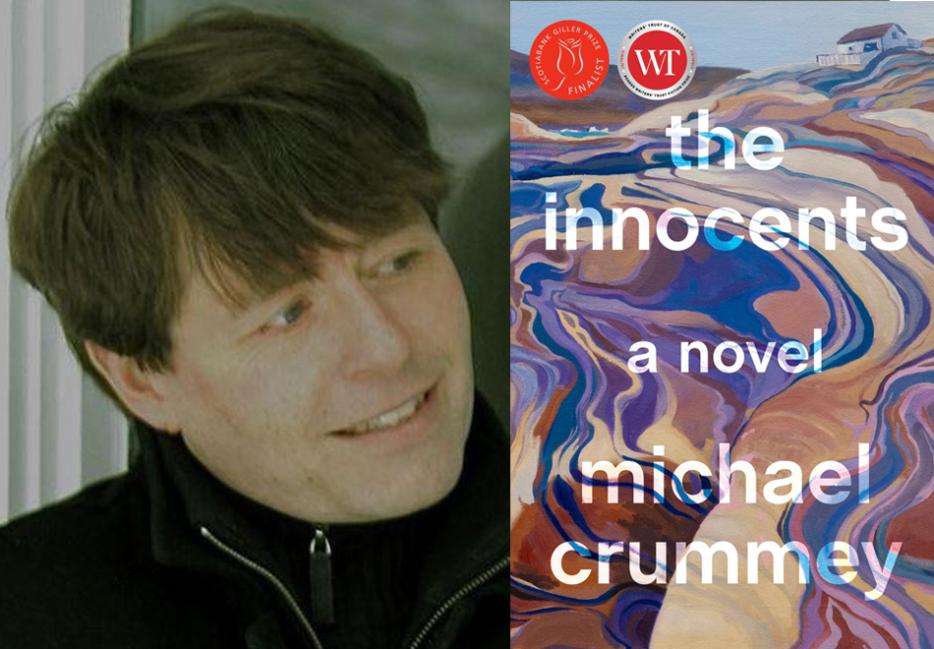

Since his 2001 debut novel River Thieves, Michael Crummey has woven together Newfoundland’s rich and often ignored history with fiction. His latest novel, The Innocents (Doubleday Canada), took years to begin and was written almost out of compulsion after a trip to an archival library.

The novel follows two young siblings, Ada and Evered, following the death of their parents and baby sister. With very little contact with the outside world, the brother and sister survive the harshest conditions. Having only each other to rely on, the siblings form a bond that is tested as they grow into adolescence.

The siblings endure unimaginable hardships, giving the reader a highly complex and rich coming of age narrative, one that Crummey was almost too afraid to explore. Through his writing, we see an empathetic portrait of what becomes of familial bonds when tested beyond their usual limits.

Sarah Hagi: You’ve mentioned how this story came to be, through reading about a clergyman’s findings. Can you get into that a bit more?

Michael Crummey: I was at the provincial archives in St. John's. I spent a lot of time there for a bunch of different projects so I was there working on something else, I don't remember what it was and it was quite a while ago. Just in the process of poking through things, I just happened on this one paragraph. It was from way back, so possibly a newspaper. And I don't know if it was the clergyman himself writing it, or if it was somebody reporting what he'd been told by the clergy. But this clergyman was traveling around the island, which was not unusual because most places didn't have a church or a clergyman. In the course of traveling around the islands, he came upon an orphaned brother and sister who were living alone in an isolated cove. It became obvious to him very quickly that the sister was pregnant and he immediately assumed that the brother was the father. The brother ended up driving him off with a rifle. There was no more information about who the brother and sister were or how old they were.

I immediately thought that would be a story, and I immediately rejected it. Like, I didn't want anything to do with it. Yeah, so I didn't take note of the source material or anything, I just sort of, I read it, and I just kept going with whatever the business was. And I mostly forgot about it, I think, But, but not completely, obviously.

What was it that stuck with you?

Every now and then I would think about those youngsters. And I think the thing that really hooked me was thinking about them in relation to my own childhood, and what it was like for me growing up. Just how unbelievably confusing it was trying to come to grips with those kinds of changes that were happening within me. Even though I grew up in a place where I had some resources and there were bits and pieces that I could try to cobble together into a picture that said something about what I was feeling, it was just appallingly confusing. And so thinking about these two children who had been left on their own completely, with no resources, with no one to turn to, and guessing that they wouldn't even really be able to have words to even try to describe what was happening, and then to end up in the situation that they ended up in, I guess I was kind of heartbroken for them. In a way I wanted to tell a story that did the opposite of what the clergyman did. I was hoping that by the end of it, that they would be left with some kind of dignity, but I didn't know how to go about that at all.

I imagine it was very difficult to write about.

I mean, one of the things I wanted to do was to provide them with a life that was more than that. I don’t want it to be the incest book. I decided what I had to do was try to put them into a life in which what happened between them, in that intimate way, was just one of the things that happened to them in the stream of things they had to deal with.

Their entire family dies within the first ten pages of the book. When you’re writing these two characters and there’s so much left to the story until the end, how was it dealing with that grief they obviously felt and with them becoming adolescents?

I mean, it's no wonder that I went so long not touching this book. I wrote that opening actually quite a while ago, maybe three and a half years ago. Then I just put it away—I thought, “I can't do it.” I didn't know if I had it in me to tell that story in a way that felt believable, and that wouldn’t just be a misery trek for readers. It wasn't until my editor Martha called me. I didn't really have anything except this [opening], it's about three thousand words. After she read it, she said, “I'd like to know more about those children.” So I kind of thought about it, as a story about childhood. I just tried to write them as real children in extreme circumstances.

What was it like dealing with the survivalist aspects of the story?

That was part of me wanting them to be situated very clearly in the rhythms of the life that people would have had at the time. My father was born in 1930. But he started fishing with his father when he was nine, down on the Labrador Coast. He says he didn't take a full share of the crew until he was eleven. And I think that's part of the reason I picked the ages I did. They’re eleven and nine when the book opens, because I thought, okay, at that point, they actually would be able to survive. They've been working their entire lives, really, to that point they have probably reached a stage where it's not out of the realm of possibility that they would be able to make a go of it. All of the survival stuff was basically just putting them in the landscape and letting the landscape happen to them.

Even though they’re so isolated, the story very clearly takes place in Newfoundland. I feel like it couldn't have happened anywhere else.

I've always said that the books that I've written have been an attempt to get Newfoundland down on paper, and to create a real sense for readers of what the place is like, and how people have lived there. With this book, I had a slightly different feeling, because I felt like the story of the brother and sister could have happened anywhere. I was just sort of happenstance that this particular story happened. But then the fact that they were in Newfoundland shaped almost the entire narrative, because the place itself was such a presence in the lives of people at the time. Just in terms of what you had to do to survive and how you could or couldn't live in that landscape.

You mentioned feeling the need to write this story to do these kids justice, do you feel like you accomplished that?

It was kind of like Martha pushed me off a ledge in a good way. I always doubt a book when I start it. But about halfway through the book, I started thinking, “I hope I don't die before I finish it.” I just had that sense that this was a story that I really wanted to see told and that I was telling it in a way that I felt good about. There was a real sense, when I was done, that it was pretty much what I hoped for. I’m happy to have it out in the world.