A decade ago, film student Brandon Harris became an accidental gentrifier of Brooklyn’s intermittently notorious Bedford-Stuyvesant neighbourhood. The brownstone-lined backdrop of early Spike Lee sets, Bed-Stuy is home to one of the country's first free Black communities, established in the 1830s. The neighbourhood's predominantly African American denizens have spanned the spectrum of socioeconomic experience ever since. Silver screen icon Lena Horne grew up in Bed-Stuy. So did Shawn Carter, who sold crack out of the Marcy Housing Projects at the neighbourhood's northwestern perimeter before rhyming about it as Jay Z. "Hold a Uzi vertical, let the thing smoke/ Y'all flirtin' with death, I be winkin' through the scope," he waxes in "Marcy Me," a verse coated in nostalgia for the artist's pre-Giuliani youth.

When Harris and his art school pals moved into Carter's old stomping grounds, just a decade and change after the height of the crack epidemic, their presence marked the beginning of a contemporary wave of demographic transition that has since accelerated. Bed-Stuy is now among the fastest-gentrifying neighbourhoods in the United States, Harris reports.

But when Harris made his initial move into the area, this wasn't yet the case. Real estate agents fibbed his Taafe Place address as falling within the boundaries of neighbouring Clinton Hill—a demographically similar enclave closer toward downtown, notable mostly for the Pratt Institute and conspicuously little else. (A fun fact is that Clinton Hill native Christopher Wallace played the opposite trick by repping Bed-Stuy when he reinvented himself as the Notorious BIG. A shared zip code just isn't enough when what you're going for is infamy.)

Unwittingly, Harris found himself a well-to-do film student in one of the country’s most notorious neighbourhoods: upwardly mobile, upper-middle-class and, incidentally, Black.

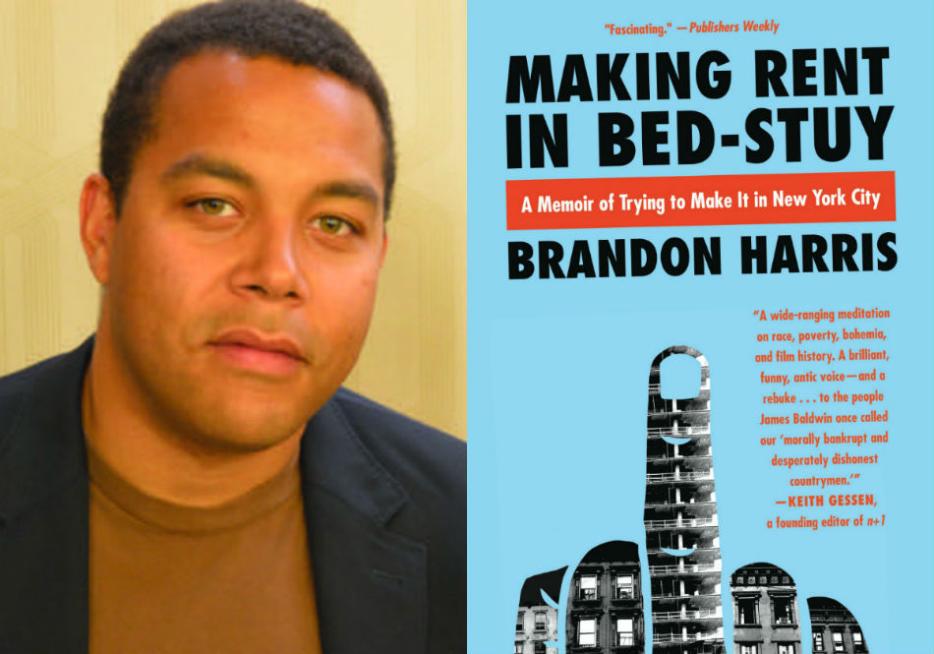

Harris’ new book, Making Rent in Bed-Stuy (HarperCollins), melds memoir and sociology to probe the history of a neighbourhood whose mythos often eclipses its truth—and picks apart the stories we tell ourselves at the intersection of race, class, and geography.

*

Kelli Korducki: So, this book is kind of a memoir and kind of a history of Black cinema and kind of a story about gentrification, plus code-switching. How would you describe how its moving parts fit together?

Brandon Harris: I guess I can only describe what I was intending to do. For me, I always saw the book as a sort of juxtaposition of a number of formats, that whether a memoir or history or cultural criticism, I’m trying to get at the root of what various individuals—including myself—have made of Bedford-Stuyvesant.

The myth of Bedford-Stuyvesant as a bulwark for Brooklyn’s Black community versus the reality of it as a place of social and material contention dating back to the 1830s—between Blacks themselves, and Dutch farm owners who sold the first black Brooklyn landowners their land, the waves of gentrification, if you will, if you want to call it that, that, that began in the 1860s and ‘70s… basically trying to get at the root of what about Bedford-Stuyvesant is so loaded.

How did what you learned about its history echo, or not echo, your own experience of the Bed-Stuy neighbourhood?

I think that Bedford-Stuyvesant is a place that grew in importance for me over the years that I lived in it. As I described in the book, it didn’t really mean much to me when I moved there. I had very little emotional stakes in what became of it, and what it had been, and what my own living there represented—what the invasion of upwardly mobile, upper middle class millennials meant.

I think in a lot of ways, the book is a way of memorializing, and of documenting, that evolving me. I wanted to reflect on how the place had accrued meaning for me, and the historical ironies of a moment we thought of as a progressive one—the Obama era—that in the end, was perhaps in a lot of ways, disastrous for African Americans. For their material wealth, for their collective political activities, and for their sense of ownership for Black spaces, not just in New York.

I could not have imagined writing this book when I was 22. I think the book represents the intellectual journey that I took to be able to write the book, but also to understand what Bed-Stuy means and meant and what it represents both historically and in its current incarnation as the fastest gentrifying neighbourhood in Brooklyn.

You make the specific choice to use the word “Negro” in a way that feels very considered. Can you explain your choice to use that word?

I think that all terms that we currently use to describe people from West Africa, or whose ancestors were from West Africa, are invented terms that come from the West. At various points in history we’ve referred to people we now refer to as African Americans as niggers, as coloured people or coloured folks, and as negroes—the term that my grandparents and any number of people from my mother’s generation used privately among Blacks themselves, in an endearing manner—Afro-Americans, Blacks, what have you. I find, for me personally, it’s the term that feels most comfortable. It’s a term that I think can be rehabilitive.

So much about contemporary Black politics has been about symbols of respect, from the mainstream, from the city founders, from the men that run this country, from whatever sources of power—usually, that is, amongst Caucasians—that African Americans seek to attain or to find some entryway into. And yet by and large, these symbols and this changing nomenclature to what is deemed “politically correct,” or using the right term… I think Black political action should be more interested in power as opposed to symbols and nomenclature.

There was that kerfuffle a few weeks ago about Bill Maher’s use of the word nigger… It was a silly thing to say, and a very shitty thing to say. But I couldn’t take any offense to that. Then, I look at Dana Schutz’s painting [of Emmett Till] in the Whitney Biennial. I can’t say that I own Black pain. It’s not for me to tell white people what to say or what to paint. What I’m more interested in is political agency, economic security. In power. It’s a completely different arena, but ultimately people conflate them.

One passage in your book that really stood out to me, that I took a picture of with my phone so as not to forget to ask you about it: You mention that in Spike Lee’s “more nuanced films,” shit-stirring characters evolve into “people willing to grasp the ambivalence of Negro existence and understand that the white man is only part of the problem and, naturally, an even bigger part of any lasting solution.” Can you explain what you mean by this?

What that referred to is rooted in the horror of living in an America dominated by white supremacy, and its various lasting legacies. Whether that’s from municipal policy or redlining, to police shootings, to the sense of insecurity that these things bestow upon Blacks. And that ambivalence that I talk about is one that, the only way to unpack it, is to think very clearly about the implications of living in a society where the majority is not going away.

I don’t think that nationalism, separatism, Liberia—none of these things have liberated Black people. We’re all Americans. Whether we like it or not, we’re all in the same boat.

The book is grounded in your own experience but also obviously deeply researched. Were you taken by surprise by anything you encountered in the process?

Yeah. A lot of the statistics about how badly African Americans fared the recession, that I encountered, were really startling to me. Like, deeply terrifying.

The idea that over half of Blacks lost over 40 percent of their wealth during the recession, that 30 percent of New York City’s Black-owned businesses closed between 2007 and 2012. It goes on and on and on.

I’ve seen this experience in my own family. My mom had a birthday party a few weeks ago, and she made this remark—that gave me great personal clarity—about how, when we moved into that home in 2005, we were upper-middle-class. And now, 12 years later, we’re working-class. And there are lots of stories like that, amongst African-American professionals.

Sometimes it seems like the market-driven mechanisms of gentrification are lost in a narrative of “white person opens coffee shop.”

There’s a lot of lazy writing about gentrification. There’s a level of rigor and thoughtfulness about what the process is and means that’s lacking. I certainly think that I have a pretty unusual personal narrative of gentrification, or class warfare, or ethnic cleansing, or what have you—because I don’t think it should be called gentrification—and I try to speak to that perspective.

So who did you write this for? The white people gentrifying Brooklyn? Me? Yourself?

I don’t know if I was thinking of a reader. I mean, I dedicated it to someone whose identity I won’t reveal, but they were someone I was very close to and who I still love, who lived in Bedford-Stuyvesant. I thought about what that person would say, and how they’d respond. But mostly, I wrote it to figure out what I knew.