After nearly five years as an infantryman in the United States Army, mostly spent deployed to Iraq, I separated from the military and moved to Brooklyn. It was more than just a change of scenery: It was a wild, pendulous swing from one extreme to another. I went from living in mostly rural places—dusty Iraqi villages in the Diyala province and tiny German hamlets—to the biggest, loudest, filthiest city in America. My life as a soldier had been spent with a diverse cross-section of working class America, a rich panoply of experiences and opinions. Everyone I knew in Brooklyn had a college degree and listened to LCD Soundsystem.

But the biggest difference was time. If my days in the Army had been highly structured and punctuated with huge, inescapable, languid bubbles in which nothing happened, then my time in Brooklyn was the exact opposite: completely devoid of form, but somehow frenetic. The temporal shift weighed on me. Days felt like they crumbled apart in high frequency, staccato moments, moving faster and faster. My life felt terrifyingly accelerated, like I was being jettisoned out of my own experience and completely losing control. I couldn’t sleep. And when I was awake, I was too frenzied to comfortably inhabit my days. Time became painful. And then I listened to the Grateful Dead.

I’d probably heard the Dead before. It would be almost impossible not to. Everyone’s at least heard of the Grateful Dead, even if they can’t sing along to any of their songs. The reputation of the band precedes it, and the legions of half-obsessed fans, known colloquially as Deadheads, follow it. As unfair as it is, those are probably the reasons why I’d never given the band a chance. I’m not a burnout. I’m not interested in listening to a band practice live onstage for five-plus hours. Why would I want to listen to a ten-minute-long guitar solo?

Looming in the background to my cultivating an ear for the Dead is the very thing that would make you want to hear a ten-minute-long guitar solo: marijuana. In Brooklyn, there’s a delivery service. You call a number—my guy was called Al Green—and an hour or so later a cyclist shows up at your door with a satchel full of little plastic baggies labeled “Sour Diesel” or “Girl Scout Cookies.”

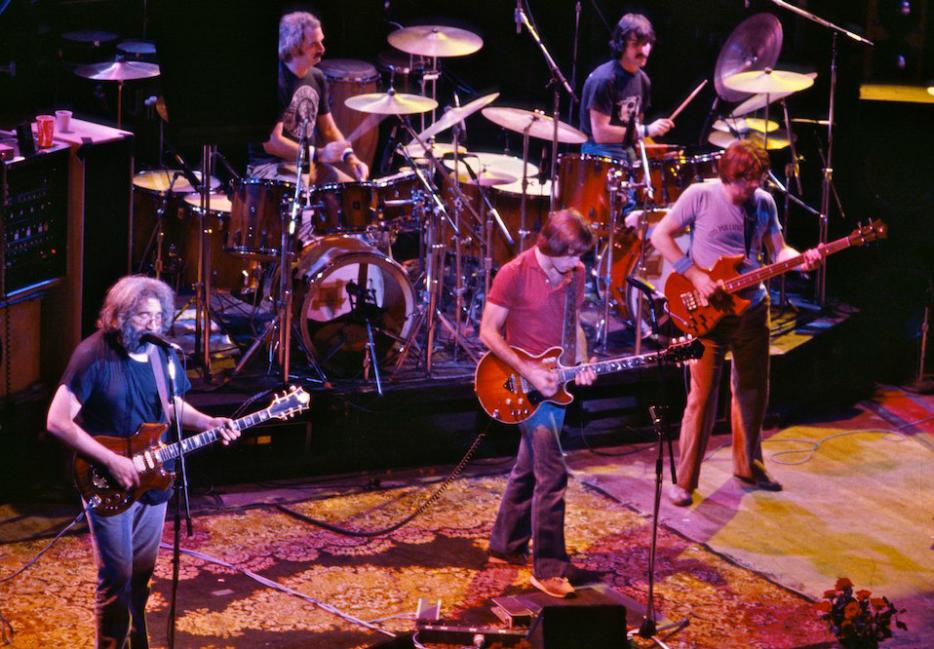

One day, after smoking a bowl of a dreamy but energizing Sativa strain, I took the advice of a recommendation from Spotify and turned on a compilation of live songs by the Grateful Dead. Never have I known an algorithm to be more accurate. The first song on the album was a version of “Sugaree” from a 1983 show in Lake Placid, New York, just a month or so before I was born. The recording is crisp. A perfectly balanced soundboard. Jerry Garcia’s guitar is up front in the mix and Brent Mydland’s gauzy, over-modulated organ is right behind it. The polyrhythmic drumming of the band’s two percussionists kind of contain the other instruments, keeping them from spinning out of control. Garcia starts out muttering a verse with a rough, nasally voice. ”When they come to take you down...when they bring that wagon ‘round...when they come to call on you...and drag your poor body down…just one thing I ask of you...just one thing for me...please forget you knew my name...my darling, Sugaree…” He starts telling a sad story, but, as soon as he finishes singing the chorus, almost stumbles into a solo. It flits around a mixolydian scale, colored by the blues but breaking itself free from formal blues structure. It’s as complex as jazz, but earthy and tired, mirroring the lyrical content. There’s something sweet and sad about it—gently pleading for forgiveness. It finds its logical conclusion in a series of crunching bar-chords. The lyrics move by so quickly that you almost miss them before another solo begins. Underneath the second solo, Bob Weir’s rhythm guitar plays bright, abstract, minimalist chords. He sounds like a garage band Keith Jarrett on the guitar. Mydland’s organ is slithering around in the background, brooding, keeping Garcia’s fluttering riffs tethered to reality. But Garcia runs scales until he finds daylight. His solo emerges into a bright clarity, then just as quickly collapses back onto itself and tenses into heavy and simple chords. Mydland’s organ flares up to fill the space. And the solo is suddenly over again.

The lyrics are repeating themselves. It’s an old story, maybe about a hanging and a secret accomplice. Or a lover making an escape. It could be about the strictures of fame, Garcia lamenting his loss of anonymity. The words are moving, but ambiguous: “shake it up now, Sugaree...maybe I’ll meet you at the jubilee...and if that jubilee don’t come...maybe I’ll meet you on the run…” The word “run” transforms into a bent note from Garcia. He springs into a cascade of triplets that fall apart, abstracted from arcane scales half-imagined in reverie. For a moment, the music sounds more like bop than rock n’ roll. Intricate patterns form, fall apart, turn into new patterns. The rest of the band simplifies their playing to contrast with Garcia’s wild foray. To give it a platform. Garcia isn’t just moving between scales and notes, but between entire American musical idioms. Jazz turns into bluegrass which turns into country which turns into barroom blues. He reaches an impossible crescendo before everyone simultaneously hits the breaks and simmers in the quiet heat of what they’ve just accomplished.

The song is long—over sixteen minutes—but the experience feels more like a single, unified, holistic event. A gestalt. The actual feeling of your own mind thinking inside a distended flow of time takes you out of the physical world of motion, of minutes counted off by clock hands or the slow decay of radioactive isotopes. Time is abstracted from physical space and is given its own autonomous life.

There are reams of literature on time and how it’s experienced, but I first noticed a description of time as experienced specifically in a Dead song—“Dead Time”—in T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, of all places:

In the knowledge derived from experience

The knowledge imposes a pattern, and falsifies,

For the pattern is new in every moment

And every moment is new and shocking

Valuation of all we have been.

Eliot’s poem is about time as a junction point, where the eternal enters into our quotidian, everyday experience. Every single disjointed moment, which in our secular imagination feels broken into segments, is actually a rupture through which a deeper, eternal, rendering of time enters our lives. I couldn’t imagine a better description of how it feels to lose oneself in the meanderings of a Dead song.

Eliot’s ideas about time were heavily influenced by the French philosopher Henri Bergson, whose work, popular among Francophiles at the turn of the last century, dealt primarily with experience, the imagination, and time. His ideas were a sort of philosophical corollary to Einstein’s scientific theories, in that both believed that time isn’t a fixed and contained constant, but is experienced differently depending on perspective. Bergson believed that we overuse spatial metaphors when we talk about time, which is a way of tricking ourselves into believing that time can be broken up into distinct and autonomous moments. In fact, the metaphor that he used to describe time was a melody. Bergson writes in Time and Free Will that “one could thus conceive succession without distinction as a mutual penetration, a solidarity, an intimate organization of elements of which would be representative of the whole, indistinguishable from it, and would not isolate itself from the whole except for abstract thought.” What he means is that a melody exists entirely holistically, as a unity. It can’t be dissected moment to moment except by the human mind removing itself from the experience of the melody as a singular event.

Entering Dead Time saved me from the moment to moment frenzy of my new civilian life. Instead of seconds piling up on each other in a claustrophobic frenzy, pummeling me with their jarring insistence, I could turn on the Dead and be reminded of how time can actually work. Or, really, what time actually is. It felt as though the nature and shape of my thoughts gradually took on the form of what I found in a Dead song. I slept at night. I enjoyed my days, fully present in each moment. And it occurred to me that maybe this kind of deep healing is the “jubilee” Garcia sang about. It feels good to no longer be on the run.