What if you could look back and pinpoint the single person whose presence in your life most determined its trajectory, forever? For many people, this exercise isn’t too tough; most of us, whether we like it or not, come from somewhere. Most of us, if we’re lucky or if we are cursed, will fall in love. Yet in life, as in fiction, the kinds of relationships that one might reflexively anoint as the most impactful of all don’t necessarily align with the obvious and omnipresent. Often, the human collisions that shape who we become are fleeting figures who scrape and press at our psyches like a palette knife with an urgency absent in those connections written into us by body or blood.

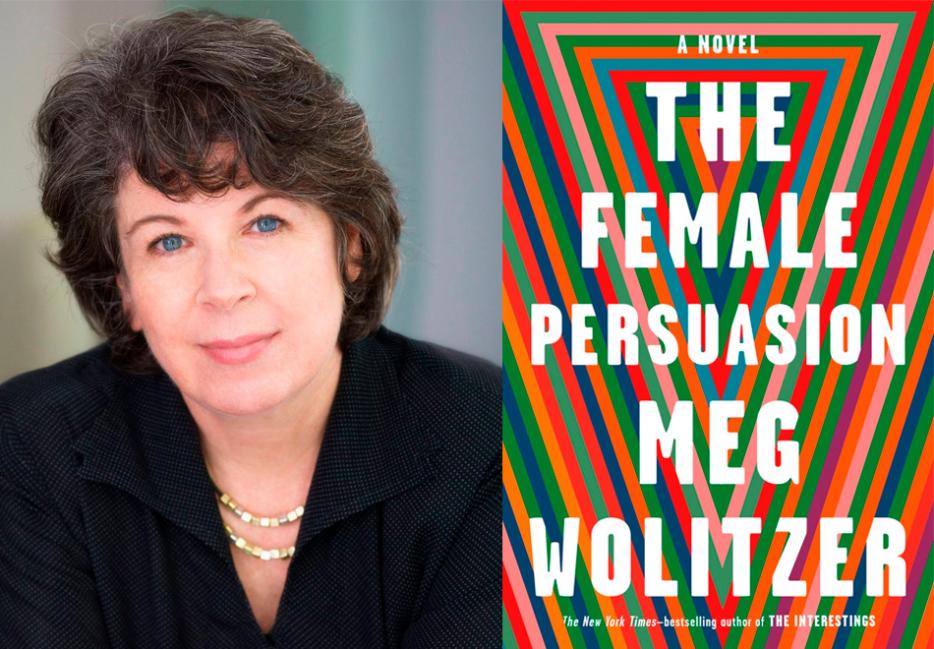

Such is the central relationship in Meg Wolitzer’s latest, long-awaited novel The Female Persuasion (Riverhead). In it, shy college freshman Greer Kadetsky encounters Faith Frank, a sort of parallel universe Gloria Steinem who has become a Grand Dame figurehead of second wave feminism (Frank’s answer to Ms., in the novel, is a magazine cheekily named Bloomer). As Frank reinvents herself upon the collapse of her iconic, yet woefully outdated, rabblerousing rag, Kadetsky—naïve but determined—sets upon the course that will take her exactly where she needs to go, and where she may never have imagined.

The novel’s publication seems fortuitously timed. While the #MeToo era has brought with it discussion of workplace sexual harassment and the everyday predation by (usually) men of (usually) women, it has also raised a heightened awareness of the generational differences between women’s attitudes. Present day conversations have produced concrete examples for not only a generation gap, but an evolution in modern feminist perspective. In a perceptive essay for Shondaland published earlier this year, author Glynnis Macnicol writes, “The Gen Gap, naturally, is not new to me. I’m just not used to being on this side of it.” Indeed, inter-generational conflict and the spectre of progress weigh prominently in The Female Persuasion, whose characters endeavour on their respective roads forward with perhaps unexpected results.

Kelli Korducki: Can you talk a bit about what prompted you to build this novel around, specifically, an inter-generational feminist mentorship?

Meg Wolitzer: I was interested in looking at the idea of a person you might meet when you’re young who changes your life forever; and I was also compelled by ideas around female power and influence. As I thought about all of this, I got excited about how these ideas could braid together, and so my story that involves inter-generational feminist mentorship came about.

In terms of this book’s release, do the timing of Me Too, Time’s Up, and related conversations feel like a fortuitous fluke to you as an author? I ask because I could see how it might also be frustrating to watch one’s parallel, self-created and self-contained universe interpreted alongside the news cycle.

I’ve been writing this book for a few years, and it is definitely being published at a heightened moment. I like the fact that that gives me a chance to have conversations about ideas around female power and misogyny, among other subjects. In the midst of all of this, since of course the book is a novel and not non-fiction, I’m also enjoying continuing to talk about its characters and story, and about novels in general. In this time of the 24-hour news cycle and all the “hot takes” out there, I have jokingly said I am the master of the warm take.

The Female Persuasion certainly engages with the criticism that second-wave feminists tend to receive online—among them, accusations of being rich, white, and insufficiently progressive—but ultimately presents us with a sympathetic, if imperfect, representative of that cohort in Faith Frank. What were you hoping for readers to take away from that character and the dynamics of her relationship with Greer?

For me, I really need to know my characters and explore them in all their human dimensions, as opposed to punishing them for their limitations. And these characters do indeed have limitations and imperfections, like all people. What I like to do when I write novels is repeatedly try to show what it’s like: being a particular person, or living in a particular moment.

I thought you really nailed the small sillinesses of feminist branding, past and present. “Bloomer” and “Fem Fatale”—the second- and third-wave feminist publications referenced, respectively, in the novel— seem to strike at the heart of how we try, extremely awkwardly, to package our movements in ways that become totally goofy and replaceable in retrospect. What do you think?

Well, there’s a playfulness in those choices I made in the book, of course. In all arenas, it’s always startling how quickly virtually everything new that’s introduced into the culture—everything named or pronounced or created—can seem self-conscious or dated.

Through the course of the novel, your four characters set out to do some things and, instead, succeed at others. What drew you to this type of narrative trajectory?

I am interested in following different characters as a way of cutting a wide swath through a story, letting it breathe and feel expansive. No one’s life is a straight road, so it made sense to me that my characters would end up with different experiences from the they had thought they would have.

A recurring theme in the novel is the idea that the next generation is expected to surpass the previous one—the immigrant kid advancing beyond his parents’ station, the daughter of transient stoners taking up the cause to save womankind—but it’s paralleled by an implication that the younger generation must also work to measure up to the previous generation, in perhaps a different and more fundamental way. Can you elaborate a little on this—or alternately, tell me if my interpretation is totally off?

I definitely am interested in the interplay between generations. For me it’s not so much that I hoped to make fixed statements about the generations, but instead explore the relentless tides of movement and slippage that affect all of us.

Were you ever a Greer? A Faith? With whom and when, and did the experience factor into your writing of this book?

I do try for invention with all my characters. I like to get to the point at which it feels as if they are people in the world, and not just in the world of my head. That said, it’s important to try to know, and really inhabit, all the characters, so that the things they do and say feel natural and even inevitable.