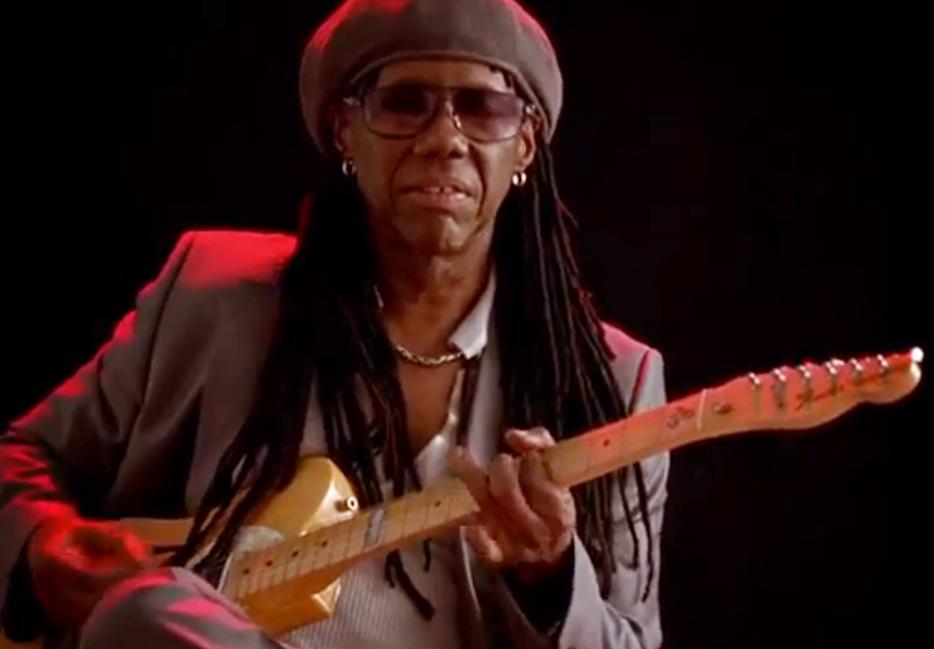

“Get Lucky,” Daft Punk’s ode to insomnia and deathless mythological birds, is currently at #3 on the Billboard Hot 100, with good reason. You can dance to it, but the beat accommodates more languorous movements too. In the New Yorker, Sasha Frere-Jones wrote that the track “creates the feeling of being on a tugboat made of bubbles while Nile Rodgers serves you liquid Valium in flute glasses and Pharrell Williams gives vague but really helpful advice.” Its parent album Random Access Memories cost several million dollars to record and promote, and you can tell; even the marketing resembled a prelude to alien contact. Websites published slideshows of the various Daft Punk helmets and an oral history of their first American show, mere humans in a muddy Wisconsin field. All I needed to get excited was Rodgers, the finest rhythm guitarist around, whose fluid guest licks seem to phase through their surroundings. It was charming seeing him jam next to two French robots, and a little moving too, not only because he built a career on studied anonymity but because he was alive at all.

Several years ago I saw Rodgers accidentally take over a keynote panel, despite the fact that it also featured the personality and hair of Janelle Monae. Everyone just wanted him to keep telling stories: about how Let’s Dance was inspired by a photo of Little Richard getting into a Cadillac, about playing Ms. Pac-Man with Madonna, about politely turning down the offer to produce a Jeff Beck cover of “Chariots of Fire.” He hinted that a memoir was coming, and although he got diagnosed with pancreatic cancer while writing it, Le Freak: An Upside-Down Story of Family, Disco and Destiny appeared near the end of 2011. I didn’t read it until this week, which kind of made me feel like the record executives who neglected to lock down Chic circa 1977.

Rodgers’ irreverent, conversational prose style understates the extraordinary arc of his life. He was born to a 14-year-old single mother and surrounded almost from that point on by dashing, drugged-out bohemians, like his Jewish beatnik stepdad. His dark skin made him the brunt of racism and colorism alike—one passage recounts the “subtle grief” he was given in an upper-class black enclave on Martha’s Vineyard. He pretty much quit school by 15, panhandling with his guitar and sleeping in a succession of crash pads and subway cars, which turned out fine. He studied the world. Whether it means music or ideas or people, Rodgers is an enthusiast, indulgent of others’ eccentricities. At one point during the late 1960s, he was both a teenage hippie and a Black Panther. In Chic, Rodgers came up with the hooks or chromatic movements and bassist Bernard Edwards simplified them, filing it all down to crisp grace.

A funk band that placed themselves in the R&B tradition, Chic were never partisans of disco per se. That genre happened to be an ideal vehicle for the atmosphere they wanted to create, sophisticated, cosmopolitan and dotted with couture labels. Its irony often went unheard—“Good Times,” released at a time of economic crisis, quotes the Depression-era standard “Happy Days Are Here Again”—but the image of black men and women dressing like European aristocrats was political in itself. Disco carried repetition forward from funk while casually discarding the archetypal cock that had been a centre of attention since before Elvis’ first swivel, and many people did not appreciate this new emphasis on the polymorphous perverse. The eventual backlash came from multiple directions—Jesse Jackson condemned the glamorous vanguard as “garbage and pollution”—but its seething core was made up of straight white men, who sensed their opportunity to restore rock, leached of any remaining blackness or queerness, to supremacy. In 1979, shock jock DJ Steve Dahl, who always lisped the word “disco” on-air, organized Disco Demolition Night at Chicago’s Comiskey Park; wearing military fatigues, he detonated a massive vinyl-filed crate before 7,000 fans stormed the baseball field in a kind of hesher fascism.

Thirty-five years later, Nile Rodgers still sounds dismayed by the angry resentment, writing that “it was like we were in some Gothic tale of elves, dragons, warriors, and monarchs.” The ex-hippie recognized the same thing his enemies did, the liberating potential of this multiracial, diva-exalting, omnisexual movement, “music reach[ing] across all social and political boundaries.” He notes that the impersonal qualities of dance music, which helped ensure commercial doom as record companies followed disco acts’ hit singles with generic LPs, could simultaneously make it more inclusive. Anonymity also allowed Chic to thrive even after their records began flopping; traditional idols might have found themselves fossilized inside familiar personae, but Rodgers and Edwards, a self-declared “opening act,” always focused on setting moods, and they segued into full-time production. Pet Shop Boys’ Neil Tennant once coined the term “imperial phase” to describe those fleeting apogees when some pop star can’t seem to make a single awkward move. Rodgers preferred to be an influential courtier, bending the ears of heirs.

The man became such a “junkie workaholic” that he barely survived to enjoy his eminence (one memorable late chapter outlines a paranoid coke breakdown culminating in the rush-delivery of a samurai sword). He became estranged from and reconciled with and finally buried Bernard Edwards, but remained Nile Rodgers, even after successfully completing rehab; when an old friend offers wintry fields of blow, he laughs it off nonjudgmentally. Random Access Memories rarely sounds so insouciant. Daft Punk hoped to recreate the disco records they once sampled, but at least as often they sound like Steely Dan playing prog rock about sad androids, brilliantly inane. You don’t walk around in a custom robot helmet if you don’t like a little vanity in your humility, and this album was designed as a monument to personal heroes and their wealthy admirers alike: a captivating, frustrating, obsessive, inconsistent extravagance. I wish more of Random Access Memories had the ease that Rodgers brings to “Get Lucky,” but then its excess might seem plutocratic rather than poignant. Given millions of dollars to spend on the world’s best musicians, who could resist trying to make “My Forbidden Lover” or “Thinking of You” anew, to chase their scented, summery air, a wisp of a synecdoche of a moment?