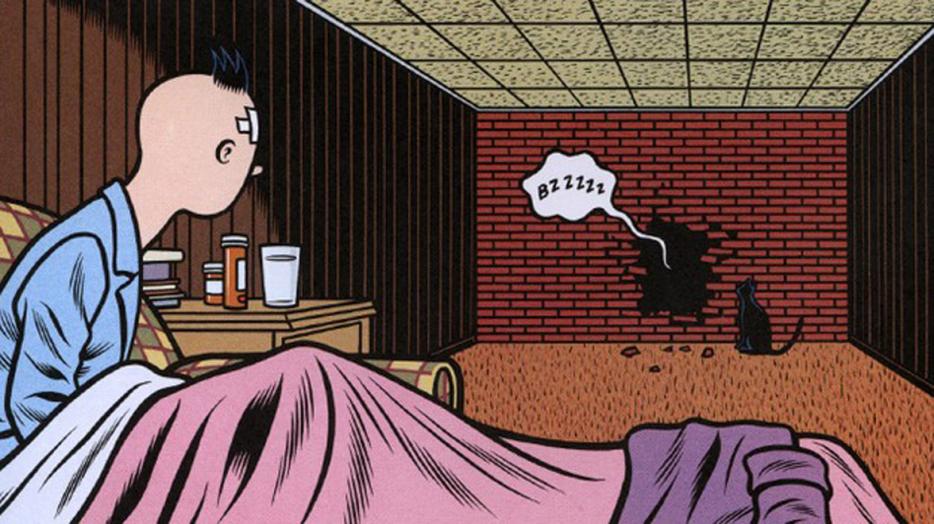

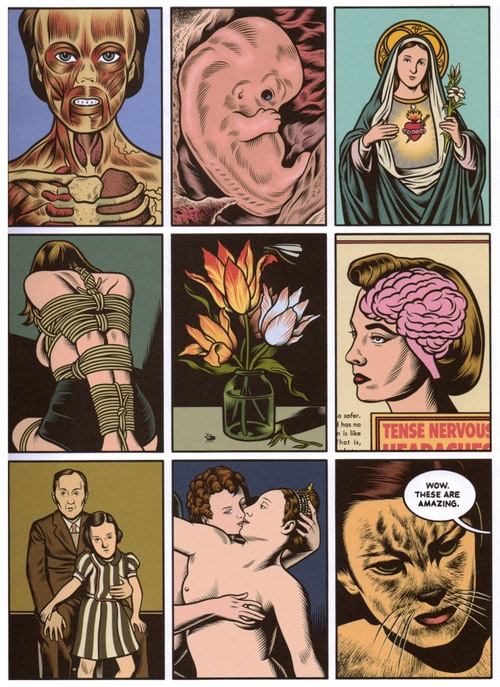

As Charles Burns’ new book The Hive nears its ominous ending, the protagonist Doug pictures a gestalt of panels from the old romance comics he’s been reading: But as I look I realize the image won’t hold…It has a life of its own.” Throughout this graphic novel, the second in a planned trilogy, certain images recur in a disorienting blur: fetal animals, scars and burns and holes, toxic pollution. Doug is sick; taking too many pills after an unknown trauma, possibly involving his troubled photographer girlfriend Sarah, he slips from a milieu of punk shows and performance art in the ‘70s Pacific Northwest to a hallucinated bazaar city, insectoid and decaying in the desert. There, with a spiky black quiff atop his head, he’s known as Nitnit—an oneiric abstraction of Tintin.

Unlike Burn’s previous work, Black Hole, where teenage misfits visit body-horror mutations upon each other, this full-colour trilogy has an Hergé/William Burroughs ferment. But the dark, hard inks and gift for an unnervingly memorable symbol remain.

I don’t want to reduce the last two books to “Tintin meets Burroughs,” like some bad Hollywood pitch, but I am curious about how you came to intermingle Hergé with these darker images, like the open wounds and the rivers of industrial sludge.

It’s kind of a darker side and a lighter side that came together, I suppose. I wanted to do a story that was based on a period of my life in the late ‘70s—’78, ‘79—when I was in art school and involved in punk music in the Bay Area, San Francisco, Oakland. I had a number of false starts, and I realized I was doing it too literally, trying to do some story about what that world was. And at a certain point I just allowed myself to let the story go where it needed to go.

One of the threads, this Tintin world—that’s something I grew up with. Now it’s very typical for people to read Tintin, see it in every bookstore, but when I was growing up, in America they published six books, by Golden Press, I think, and they were American translations as opposed to the British translations. They didn’t do very well. They never found the audience. I’ve never talked to anyone of my generation who grew up reading those books and had those kinds of influences. You talk to any French, Belgian, Dutch kid, or someone growing up there, it’s like Walt Disney, it’s everywhere. He’s a national hero in Belgium.

Like [Japanese cartoonist-manga artist] Osamu Tezuka.

Like Tezuka, sure. That was a big influence on me when I was growing up. I was given those books early on, and I think I internalized them, I looked at them before I could even read. And…even though it was a foreign world to me, I felt like I could really enter into it. You have Tintin traveling to some unspecific Middle Eastern country—I didn’t know what that was, but I found my way into it. And I think that came up to the surface in the story that I’m writing now.

The William Burroughs aspect of it certainly came out from the time period that I just described, being influenced by punk music, being in art school. That was part of my world, what I was reading. He was this incredibly visual writer and a very funny writer. He was kind of embraced by—it sounds dumb talking about punk music, but—it was the post-hippie era, when everything was supposed to be nice and sweet and wasn’t, and it was nice to acknowledge that there was this dark, fucked-up world out there, and also acknowledge it with a certain amount of humour. That’s part of it. Burroughs also had this…I’m trying to think of the right word…a collaged way of pulling imagery and ideas together that somehow worked for me. A composite city.

It’s almost more comics-like than a lot of other writers, or at least more visual.

For me it is, and I don’t want to say “oh, it’s because he was taking opiates,” but of course my character is taking opiates and slipping in and out of dreams. There’s something very lucid about the way he describes this grotesque world he’s—this Interzone that Burroughs talks about, which is a combination of Mexico City, New Orleans, St. Louis, Tangier, just putting all these little elements together. Walking through jungles in South America. Anyway, that found its way into the work.

In that late ‘70s period—were you already making comics at that time? I saw another recent interview with you were you mentioned, um, you know the cardboard house that they make in The Hive, that Louise Bourgeois thing? You said something like “I did make a cardboard house and take photographs of my naked girlfriend wearing that.”

I was the kid that drew in high school and I really didn’t have any sense of myself other than being an artist, and I didn’t know what that was, so I went to art school. I was extremely naïve, but I was kind of centred in the sense that I would get myself how-to books and say, “okay, you need to use India ink on larger-sized paper.” I would do that kind of research on my own, and by the time I was in junior high and high school I was creating what would be printable, finished pieces, ready for reproduction. Probably more influenced by American underground comics than anything else. I went to art school and tried a lot of things. I tried photography—I was open-minded in the sense of, I’ll try this, that sounds interesting. Sculpture, video art, I’ve talked before about doing really bad performance art—

But wasn’t everyone at that time? [laughs]

Not everyone I knew, but yeah. There was this incredible—for me it was just like, my God, here’s a half-inch black-and-white reel-to-reel camera that I can check out and make videos with. Having access to that seemed amazing. Of course now it’s just such a given, but at that point—I can put something on this TV monitor! I tried all of those things out, and was open enough to discover a lot of things that fed into the work I do now. So I wasn’t just looking at comics, but by the time I graduated from art school I realized that I wanted to tell stories. I liked the accessibility of working for print, even if I was self-publishing. I liked that idea that you could hand something to someone. It didn’t have this preciousness that my understanding of fine art was—you make an object and it gets sold or it doesn’t get sold, or at best it gets put in a museum somewhere. And I think at that point I very slowly started teaching myself how to write, I guess. I’d done more art comics, things really focused on the visuals, and I had to teach myself how to tell stories.

When you mentioned the performance art thing—I’ve been reading a lot of old Michael Gira interviews lately… you guys are probably about the same age, and he was around California at the same time.

I know of him, I know the music, but my guess is around the same age, yeah.

There’s this one performance art piece that he’s mentioned—and people ask him about this a lot – which I’m almost haunted by, where he tried to have, as he put it, “impersonal-as-possible” sex with somebody.

Oh my God.

He seems ambivalent about a lot of things he did back then.

As we all should be. I hope, 20 years from now, you’ll look back and go “ah, my God…”

I guess he found a woman that was interested, whom he’d never met, and they wrote down their respective sexual fantasies, or recorded them, and then there was a big show…

In front of an audience?

Yeah.

Wow.

There’s a band playing downstairs or something, and they were naked, and they had these tape players strapped onto them while they were blindfolded, and they crawled around in the dark trying to find each other’s voices.

Ah, okay. Yeah. I mean, I did things that were stupid or—that’s pretty stupid, actually. No, I did things like…I built a cardboard robot, a seated life-size robot like a ventriloquist’s dummy, and I could reach behind it and move the head. And the resolution of those old videos is so low that you don’t have be a real ventriloquist. So I was sitting with my robot wife, or robot girlfriend, and having a conversation with her. I don’t think I’ve ever told that story before. But anyway, that’s more the sort of things I would do. Not in front of—if there was ever an audience involved, it was very few people. I had a friend who had seen the book, seen X’ed Out, and you see the protagonist putting on a mask, putting a cassette [machine] ‘round his neck—

The cassette full of noise.

Yeah. My friend was saying, “Oh yeah, I remember that time you got up and introduced a band, it was in San Francisco, you had a tape recorder ‘round your neck, and you took the microphone and you turned on the cassette.” I kind of never remembered that. Between the two of us we could not figure out who the band was. It had to be someone I knew—how could that work out otherwise? I did other things with tape recorders around my neck. It’s all based on something I did, or something I thought about or experienced at the time.

I remember reading X’ed Out for the first time, looking at the somewhat rounder lines in the otherworldly sequences—your style is very different from ligne claire, but I had this mini-epiphany, that maybe you and Hergé are similarly methodical, or controlled?

Controlled, maybe? Again, I mentioned growing up and reading those books, and even though I absolutely loved the linework and the colour and everything else—I don’t know whether I was too intimidated by it, but he’s not someone I really imitated, growing up. I for some reason was drawn towards the kind of classic American comics rendering from the ‘40s and ‘50s. I saw that early on too. I’m not sure why, but that’s where I was drawn toward. There’s something darker and richer to me—not richer, that’s not the right word, but something that attracted me to that much darker look. When I started doing this series of books, because I wanted to do a colour book, I was looking at Hergé: the size of the book is exactly the same size, the image size on the page is exactly the same as Tintin books. And they’re about the same number of…I think there’s a few less pages per album. I also realized that it couldn’t be quite as dark as my other work to let the colour do its job. Thinking about what colour does and how I’d be able to use it to tell a story. Opening up a lot and letting the colour do what black does in my other work.

And I didn’t expect this to happen at all, but in The Hive you incorporate this whole other stream of cartooning with the romance comics that they’re reading.

It has to do with the fact that the story is a romance story in a way, and I’ve always been drawn to those classic American romance comics. There’s a real range of them. Some are really, really bad—even the bad ones are pretty good.

There’s some great artists—Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby, they drew a bunch of those. There’s some ‘60s Marvel ones with vintage Stan Lee pandering. I remember one amazing cover I saw with a line like “dedicated to the fabulous, fearless females of women’s lib.”

There you go. Yeah, I was drawn to those things. And part of it too was, during the late ‘70s, I would buy stacks of romance comics for my girlfriend. There was a certain kind of jokiness there, but we both actually enjoyed them. It was fun looking at those ‘60s fashions and ‘60s attitudes. That was also something that got picked up by the punk era, that fashion, looking backwards to the pre-hippie era. Garage bands and girls in miniskirts.

I thought it was striking that you not only brought in Louise Bourgeois, but one of her drawings rather than the sculptures, that creepy image of the woman confined inside the house.

That was another thing I saw when I was in art school. I didn’t know her work at that point. I think it was an ink drawing for a catalogue for an early show she had in New York, of paintings related to that subject matter. That maison—excuse my inability to pronounce any French word—I think it was on the cover of a book of feminist essays on women in the arts. I don’t remember the title of the book, I didn’t know anything about her, but I was instantly taken by that image. There’s just something absurd about it, but also very thought-provoking, a great image. Humourous but also strange.

There’s pieces where I would take a Xerox of something—I have all those images that I’ve held onto. Not necessarily always analyzing them, but when I’m drawn to something I’ll pay attention to it, try to figure out why that’s interesting. Why is a house for a head something intriguing, thinking about compartmentalizing someone’s thoughts and ideas in various rooms? So that’s something I wanted to be part of the story as well. Most of my stories have some reference or an idea of a façade or a surface that’s being presented to the world, and then an internal world versus this external presentation. I didn’t explain that very well, but that’s something I come back to again and again.

This isn’t even a question, but I did really like the way Doug and Sarah’s haircuts kind of merge or dovetail.

I remember very specifically, most of my friends had long hair, myself included, and then, fall of 1977, everyone cut their hair [laughs]. It was like, okay, we’re turning our backs on that hippie world, or post-hippie world. Whatever idealism was there was long gone. People were taking drugs because it felt good to take drugs, nothing to do with a sense of enlightenment anymore. I wanted to show that as well. You were asking before about the Hergé thing—for me it was a springboard into the story, but ultimately it doesn’t have much to do with [it], other than some visual cues. It’s not a Dark Tintin story. It’s not like, here’s Anti-Tintin.

I have to ask you about OK Soda [CB laughs], because I’m kind of stupidly obsessed with it. How did you become involved with that weird thing?

Either illustrations or doing advertising, most of that stuff just always came as a phone call or writing me or something. This was a while back. And it was just a matter of—they might even have sent me a dummy, or they’d used some existing work, like, “this is what we think, what do you think?” I’m pretty sure it was art-directed before they even contacted me, they’d worked through all that. I remember seeing the mockup for one of the first cans where they used my artwork, and I said, “this is probably a crude version of what they’ll eventually do,” but no, it was the actual artwork, hand-lettering, a very odd look to it. It never found its audience, that’s for sure. It was test-marketed in maybe four or five cities in the U.S., and I think my art’s on three different cans.

Yeah, it’s you and Dan Clowes.

Dan and I, and then one or two other artists, but ours were probably more recognizable as a certain style.

I mean, I was watching Power Rangers at that time, I wasn’t the target audience, but from what I’ve heard about [the early ‘90s], it seems symptomatic of this moment of mass insanity, when a bunch of corporations thought that any random Sub Pop band could make millions of dollars with clever enough marketing.

Yeah, it was certainly an attempt to cash in on that, I suppose. And maybe it was marketing researchers telling the Coca-Cola Company that you have to have this edgy, ironic drink for twenty-somethings, whatever they were called at that point, but it sure didn’t catch on. I did artwork that was never used, and I know that Dan did artwork that was never used, and I know that they used some of my stuff for TV spots—maybe I’ve seen some on the internet, but anyway, they were planning on going ahead with it, and at that point I think three new cans were supposed to come out every month. The idea was that the “OK” logo would be the only constant. I think they had a 1-800 number—the internet was around, but it wasn’t what it is now. There was still “make a phone call or write us a letter,” it was right on that cusp.

Have you ever tasted it?

No, I haven’t. I’ve had friends who’ve told me that—no, I never have.

According to Wikipedia it tastes kind of like a cherry Dr. Pepper?

Yeah, or like some—I don’t know if it was grape, or cherry, but a fruit…It was described to me as, like, you took sweet tea and put something else in it. It didn’t sound very appealing to me. I remember Dan Clowes said they sent him a six-pack or something like that and they had a little tasting party. I could imagine them all sitting around with little glasses of OK Soda. It’s a funny image [CR laughs].

I’m wondering—what is your process like? Do you use computers now? Has it changed much since Black Hole?

During the time I was working on Black Hole, probably maybe in the middle there, I finally had to submit to getting a computer and learning how to scan my artwork, how to do colour that way, just because that was a necessity. And luckily I had friends who were able to push me in the right direction—I had a good friend, John Coromoto, who basically walked me through everything, almost like a cookbook, saying “okay, on the right there you’ll see a little box…” But the only thing I really use it for is scanning the artwork. I do everything in the same way I always have. Rather than having someone else colour my work for me or scan it for me I’m doing it all by myself. What’s great is that, especially the way that I work, you have an incredible amount of control—you’re working for print, and so you can control the colour as close as anyone can get. You’re not handing anything off to anyone else to mess with.

I’m kind of taken aback by how much some cartoonists my age employ—I was talking to Michael DeForge, because I love his work and wanted to maybe buy a page of it, and he basically said “oh, there aren’t any, because I sketch and then it’s all drawn on [the tablet]…”

Sure, I think there’s a lot of people who do that. And my sense is just, whatever works. I love that tactile feeling of a pencil on a piece of paper, bright light that’s bouncing off a white sheet as opposed to something that’s radiating from a screen. I’ve tried using some of the pads for drawing, but somehow, whatever was going on with my hand and looking at that screen, I couldn’t sort that out. If I’m sitting there dumping flat colour on the screen, I can do that, I can correct whatever shmutz that’s on my artwork, but other than that, it’s all—here’s a pencil line, here’s ink on a piece of paper, that’s all it is, pretty straightforward. Very traditional. It’s the same material one used at the turn of the last century.

I have one last question, a more frivolous question, which is: have you heard that Kristen Stewart apparently loves Black Hole?

This is where I’m really going to sound like an idiot—tell me who that is.

Oh, she’s an actor—she’s in those Twilight movies.

Oh, okay, yeah. It’s funny, I find myself congratulating myself—”oh, I’ve heard of Twilight”—even though it’s the most popular…

She’s in that new On the Road adaptation. There was a profile in some fashion magazine, and I guess they went to a bookstore, and she finds a copy of the book, and she’s like “oh, Black Hole, this is so gross, it’s so amazing, I want to be in this movie!”

That’s funny. Not to be insulting to her or anybody, but I’m pretty out-of-it when it comes to the world of Hollywood. People ask me, have you seen this movie, this movie, this director, and I’m like, “Umm…” I eventually find the things I’m interested in, but I’m not on top of it, that’s for sure. So I don’t have a good answer. “Who’s that?” I suppose that’s my bad answer.

She’s not the only—Kurt Cobain’s daughter has an Al Columbia tattoo.

Yeah, that I can understand. That whole Seattle connection. That makes a lot of sense. I was just talking with Chris Ware, we were in Brooklyn [for the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival], and someone came up to him with a tattoo of the fat Superman character [from Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan] that was still throbbing and pink-looking, that had just been scratched into his skin the day before. I’ve occasionally seen the odd tattoo, or someone sends me a photo. Sometimes you think, Aww, you ruined yourself, shit! Sometimes it’s like having your drawing interpreted by somebody who doesn’t know how to draw.