On the stone walls surrounding Toronto’s Provincial Lunatic Asylum (now the Centre For Addiction and Mental Health), there are hundreds of inscriptions from patients, dating back to the 1860s. “Born to be murdered” reads one. Another advises fellow patients on how to escape. Back then, Toronto’s mental health system modelled itself on Victorian prisons, forced labour and all: patients were beaten, starved, and caged off. The public perception of the mentally ill was shaped largely by news media reports that were moral, sensational, and reported from a great distance; the voices of the “lunatics” themselves were scribbles on asylum walls.

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health is now a state-of-the-art treatment facility with manicured public grounds, a patients’ rights board, and glossy annual campaigns to raise awareness about mental illness. Since the 1860s, mental health policy has evolved towards a biomedical approach. Diagnoses like depression or schizophrenia, once treated as signs of moral degeneracy, are now framed like cancer or spinal cord injuries—unfortunate accidents of biology, but more or less treatable, thanks to global advances in psychopharmacology (particularly the advent of side effect–lite antidepressants and antipsychotics in the 1990s). We accept that CAMH looks like a hospital for the same reason people accepted that the lunatic asylum looked like a prison: it reflects public attitudes about mental illness.

But the biomedical approach, though comparatively humane, has its critics, and it took hold alongside an alternative perspective. In the 1960s, hippie-ish thinkers like R.D. Laing began questioning the therapeutic value of drugs and clinical psychiatry. Such ideas had traction among psychiatric survivors, as they called themselves, who began organizing into “therapeutic communities” that de-emphasized medication in favour of political activism and interpersonal support. On September 18, 1993, a small group of ex-patients took to the streets in Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood in response to municipal bylaws restricting housing options for discharged psychiatric patients. The marches became an annual thing, and a movement—known as Mad Pride—was born. By 2000, when the event was expanded to a weeklong celebration and moved to July to better link up with Gay Pride, there were Mad Pride events in Sydney, Cape Town, San Francisco, and London. The events have become raucous festivals, with “bed push” parades, plays and movie screenings, and, in London, “Mad Raves” and concerts. In 2007, July 14 was declared Toronto’s “official Mad Pride Day” by then mayor David Miller.

Just as the Stonewall riots gave way to a global gay rights movement, so a march for fair housing evolved into an entire identity politic. “Madvocates” question the dominant narrative about mental health, which holds that the people we call schizophrenic, bipolar, psychotic, or personality disordered are chemically ill. Instead, Mad Pride considers “madness” a disposition, a personality trait. “Madness is an aspect of my identity—who I am and how I experience the world,” writes Alisa, who is active in the Mad Pride community. “[It’s] not an ‘illness’ that is separate from me or a collection of ‘symptoms’ I want cured.” Madvocates’ attitudes vary: some identify with their diagnoses, see psychiatrists, and take medication. But others think diagnoses are bullshit, identify as “mad geniuses” or prophets, and consider medication and therapy tools of anti-mad oppression.

Mayoral endorsements aside, Mad Pride has mostly flourished under the public radar. Its spokespeople aren’t featured in public awareness campaigns; hospitals do not refer patients to parades. Media reports on Mad Pride events have a consistent tone of polite bafflement. It’s not hard to understand why. The gist of Mad Pride—that madness is an identity to be celebrated—contradicts the notion that madness is a disease. After all, if madness isn’t an illness, why would you see a psychiatrist or take your Abilify?

To help me understand just how different the Mad Pride approach is, Alisa sends me links to movement newsletters and essays. Reading through them, flicking through pictures of this year’s “Mad Hatter Tea Party,” featuring participants dancing for photographers in their best crazy-person headwear, I see a lot of joy—an emotion I’d never associated with mental illness. A century ago, these people would have been strapped to beds in asylums; on modern TV, they’d be pushed out behind podiums to utter pious, cautionary speeches. But at Mad Pride events, they grin and dance. I start to appreciate why medication, for many madvocates, is beside the point.

*

I became interested in Mad Pride after my best friend, Rebecca, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2006. Prior to this, she seemed to me the very definition of the eccentric genius: creative, impulsive—and prone to crushing fits of paranoia and self-sabotage. After her diagnosis, I came to understand these qualities as symptoms that waxed and waned according to her ever-changing medication regimen. I sometimes describe my friend’s condition as a monster that lives inside her. Sometimes the monster is small and dormant. Other times, it is huge and raging and seems to have swallowed her whole. During these episodes, I’ve noticed, there is a new dimension to her suffering. She asks: “Did that sound crazy?” and “Is this a feeling, or a delusion?” It is as if she lives each moment twice: first through direct experience, and then through the lens of a perceived non-crazy other.

In a 2006 essay for the Guardian, novelist Clare Allen describes how easily the stigma surrounding mental illness leads one to self-hate: “[It] robs people of their experience, effectively tells them that for months or for years, or recurrently (as is often the case), they didn’t exist at all.” With Rebecca, it’s not just stigma that renders a good chunk of her experiences illegitimate—it’s the diagnosis itself, the label that compels her to distinguish her “real” feelings from her symptoms. And her friends and family do that too; we’re always trying to tell the difference. Rebecca’s diagnosis as bipolar has effectively thrown her basic identity into question: where does Rebecca end, and the monster begin?

“What Mad Pride does that is missing in psychiatry,” Rebecca says, “is give you a way of relating to your mental illness. It says, OK, here’s a way to see yourself.”

Seen through the lens of Mad Pride, Rebecca comes into relief for me in a new way. I think, for the first time, she must be exhausted.

*

Throughout her teens and twenties, Marya Hornbacher, acclaimed author of Wasted and Madness, was at the mercy of her violent mood swings. At times, she felt “incredibly creative, intellectually expansive, productive, generative of ideas and language.” At other points, she was catatonic, her mind a “living hell.” Still, she believed that to medicate herself—to dull her mania, even as it was accompanied by crushing lows—would be to close off that special dimension of experience that made her such a wildly creative thinker and artist. If Van Gogh were on lithium, would we still have Sunflowers? (The trope of the creative eccentric is popular among madvocates: “Insane Genius” awards are presented at annual Mad Pride events, and many consider Van Gogh a patron saint.)

Hornbacher’s accomplishments bolstered her self-perception. While she ricocheted around the mood spectrum, she authored three books, including Wasted, which became an instant classic of modern memoir; held coveted lecturing positions; and gained Pushcart nominations for both her non-fiction and her poetry. Her volatile relationships with men, drinking binges, and spur-of-the-moment travels seemed to give her writing a characteristic authenticity, a raw-nerve emotional oomph. So Hornbacher resisted treatment for years—even when she found herself suicidal, delusional, unable to leave her bed for weeks. She saw psychiatrists only sporadically, usually during a rocky low, and abandoned treatment when the highs returned. She hated the side effects of medication, and feared fully adopting a diagnosis as bipolar: it would demand completely rethinking who she was.

Three rock bottoms later, including a near-fatal attempt to self-injure, Hornbacher saw that accepting her diagnosis was a matter of life and death. In Madness, she describes her turning point as a process of re-identification: “I am no longer young, wild, crazy, a little nuts,” she writes. “I’m a crazy lady.” Coming to terms with her diagnosis, Hornbacher tells me over email, meant relinquishing the idea that mania made her productive, and instead identifying as someone with an illness “just like diabetes.” As difficult and unsexy as it was, Hornbacher writes, it was key to saving her life. After years of playing fast and loose with medication, alcohol, and sleep, she now follows a strict regimen of medication, therapy, and self-help techniques that minimize her symptoms and keep thoughts of suicide at bay. Her writing is as emotionally raw and compelling as ever.

“[It’s] not only simplistic, but risky,” Hornbacher now says of the “mad genius” stereotype. “Psychiatric illnesses [are] disorders of the brain that are treatable, manageable, physical conditions. There is vastly too much biological evidence of mental illness—qua illness—to pretend it does not exist.” The idea of the brilliant madman suggests that treatment kills creativity: “Many people who believe this will not seek psychiatric treatment because they fear losing this elemental part of their lives.” And patients who resist treatment, Hornbacher adds, are at serious risk for death by suicide—the rate of which, among people with serious mental disorders, can be as much as 20 times as high as among the general population. Twenty-five percent of people with Bipolar I—Hornbacher’s own diagnosis—will attempt to take their own lives.

*

While resisting treatment is a big risk for people with mental illnesses, so is stigma. In fact, stigma is widely considered a leading cause of medical “noncompliance.” In 2001, the World Health Organization declared that stigma was the “single most important barrier to overcome in the [mental illness] community.” According to some studies, two-thirds of all people with mental health conditions avoid seeking treatment because of negative public perceptions about their condition.

That stigma against mental illness lingers, in various interpersonal and systemic forms, is not entirely surprising given the fact that, for most of its history, Canada treated the mentally ill as subhuman. Over the 20th century, countless people were subjected to involuntary treatments of dubious value, such as lobotomies and insulin therapy (a process that carried a high risk of diabetes, brain damage, and death). Despite a mass wave of reforms in the 1960s and '70s, throughout most Canadian jurisdictions, patients who are involuntarily committed to care—who are judged to be of harm to themselves or others—may be incarcerated, forcibly subjected to electro-convulsive therapy for periods of months, and faced with limited access to the court system.

Stigma also plays out subtly, on a personal level, in interactions that seem neutral or even positive to outsiders. When I ask Hornbacher about stigma, expecting her to repeat abuses she’d experienced in hospitals or treatment centres, she responds with a story:

I was giving a lecture in support of an organization that provides crisis services to people experiencing emotional or mental health distress. After the lecture, a woman who actually worked for the organization came up to me, patted me on the hand, and told me how brave I was, which frankly had no bearing on anything and is of course extremely patronizing. She asked me to sign her book, and as I did, she gasped.

“Is that a wedding ring on your hand?” she asked in disbelief.

I said, Well, yes, it is.

“You’re married?”

I felt this was self-evident from the foregoing, but said yes, I am.

“Oh!” she said, “he must be a wonderful man!”

I was a little put out by this—the implication than anyone married to me must be quite marvelous is either insulting or undeservedly complimentary—but I smiled and said, Oh, certainly, he is.

A look of concern crossed her face. “But you don’t have children, do you?”

I said I did not.

“Thank goodness!” she said, relieved. “I wouldn’t think you’d want to pass on your genes!”

*

Mad Pride addresses stigma through methods gleaned from 20th-century identity politics. Its models are clearly Black Pride, Women’s Liberation, and Gay Pride—movements demanding a sensitivity to how difference shapes a person’s experience, and to the history of stigma and abuse that comes with it. Mad Pride implies that its adherents are part of a culture: a community with its own values and practices, to be taken seriously and treated with as much regard as any other marginalized group—say, the LGBTQ community—demands.

The comparison Mad Pride draws between itself and Gay Pride is less ludicrous than it might seem at first. As recently as 1974, homosexuality was listed in the DSM, the diagnostic bible of mental disorders. While data is spotty, most experts agree that the suicide rate for gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth in Canada is higher than among the general population (American studies estimate it at four times higher). Of course, no one in their right mind now considers being gay a medical condition. Higher suicide rates among LGBTQ youth are typically understood through the “minority stress” theory, which argues that cultural stigma, systemic discrimination, and bullying make LGBTQ kids more susceptible to depression.

Significantly, the minority stress theory points to gaps in the biomedical model of mental illness. Since the mid-2000s, researchers have found increasing evidence that schizophrenia—long held up as an example of the pure brain disorder—is in fact determined by a delicate interplay of factors: social, experiential, chemical, and political. The experience of marginalization, including physical abuse and bullying, plays a key role in activating the mental disorder. Accordingly, helping individuals become part of a community can aid in recovery: recent studies show that when you increase access to stable housing for schizophrenics, their psychotic symptoms lessen—even if they’re not taking medication.

This links up with what we know about homosexuality and suicide: the more supportive the political, social, and familial environment for any given LGBTQ kid, the more likely he or she is to be mentally well-adjusted—and the lower the risk of suicide.

Beyond stigma, of course, the comparison crumbles. Being queer doesn’t make it difficult to hold down a job, or eat regularly, or appreciate the difference between fantasy and reality. In the end, there are aspects of mental illness that are simply impossible to square with the going definition of identity. “Comparing a mental illness—which is in fact an illness—to being gay, which in fact is nothing like an illness—is incredibly offensive,” Hornbacher tells me. “There is a way, and a need, to treat my mental illness; there is neither a way nor a need to treat my sexual identity.”

*

When I ask Rebecca about mad culture, she tells me that one of the most vicious and reliable aspects of mental illness is how it isolates and disconnects. Being part of a community of survivors can be very helpful, she says, but can only realistically happen once medical treatment is in place. Some of the best progress she’s made, she admits, was during her stay at an American treatment centre where patients lived, ate, and worked together “as a fucked-up family.” But, she points out, “we were all on our meds.”

When she is off her medication, Rebecca says, she withdraws: her delusions make it difficult for her to connect with friends and family members, even read the news or see a movie. I ask her to look at some of the Mad Pride community events, the parades and lectures and CDs. “That’s great, but the sense I get is that these are all high-functioning people,” she replies. “Someone who is in crisis—no way they’re making it out to a fair or writing letters to government. They’re at home crying or in the thick of a delusion. You can’t be pro-community but anti-treatment, that’s just not workable.” Rebecca also points out that it’s no surprise Mad Pride began, and remains most popular, in Canada—a country with an accessible (though by no means perfectly workable) health care system.

I read her a section of Pete Shaughnessy’s seminal Mad Pride essay, “Into the Deep End”: “I’m walking around as a product of emotional and physical abuse. Broken relationships, no meaningful employment, stressful housing and I’m taking a tablet for the symptoms.”

“Yeah,” Rebecca says, “so if I break my leg, and someone’s like ‘here’s some information about how your broken leg is actually society’s fault,’ I’d be like ‘great, but first, can I have a cast for my broken leg because it’s broken and it hurts?’”

Shaughnessy died by suicide in 2002, a fact he seemed to anticipate in his writing, which often posits suicide as a logical response to an oppressive and crazy world. (“This is hell,” he advises a suicidal friend. “It can be no worse after.”)

“That’s exactly how mentally ill people think,” Rebecca says. “The fact that he wrote that is really telling.”

My friend speaks lucidly about the depressive mindset for ten or so minutes, and then interrupts herself, angrily: “No. I’m not going celebrate the thing that’s destroyed my life.”

Before we hang up, she repeats it, presumably because she knows I’m going straight to my laptop to transcribe her words: “Alex, this has destroyed my fucking life.”

*

The biomedical view sees mental illness as a foe to be defeated. Mad Pride sees it as an identity. But a third approach, sometimes called the “Spectrum of Wellbeing,” complicates the distinction between mental illness and what we consider to be perfect sanity. Ultimately, stigma may lie in our tendency to distinguish mental illness from everyday experiences such as stress, grief, or relationship problems—the stuff we consider “normal.”

“Stigma rests on perceived difference,” explains Lila Knighton, a social worker with a private practice in downtown Toronto, “and the surest way to create the appearance of difference is to talk about mental illness in a way that separates it from the lives it affects.” Plus, she says, “when subclinical issues are included, almost everyone has struggled with their mental health at one time or another.”

I think about a breakup I went through where I wasn’t able to eat for over a month, and a general anxiety around paying my bills that had me waking up, every morning, with the exact amount of my outstanding student loan etched on my eyelids. That’s subclinical, or “normal” stuff, according to the old biomedical model; I don’t have a brain chemistry problem, I just have “issues.” But seen through the spectrum of wellbeing, I was struggling with my mental health—less acutely, but just as certainly as my friend has. In other words, we all have monsters inside us that may or may not be who we “really” are. The difference between my monster and Rebecca’s monster may be one of degree rather than kind.

Which means that, in terms of therapy, “there’s no one-size fits all here,” Knighton says. While some clients may find comfort in distancing themselves from their diagnoses, others benefit from community, from reclaiming words like “crazy,” accepting their experience as part of their identity. These Mad Pride–like approaches can lessen one’s internal stigma: it’s no more shameful to experience depression than to freak out about one’s bills. The problem with Mad Pride isn’t that it considers symptoms expressions of identity; it’s that it only does so for symptoms on the extreme, “unhealthy” end of the mental health spectrum. It posits a greater difference between the “mad” and the so-called sane, and in doing so, makes it difficult for us to relate.

*

While I’m researching this article, Rebecca indicates by Facebook status update that she is feeling productive, sad, proud, and depressed. I suspect—but don’t know—that she may be self-altering her medication. What I do know is that each of these sensations will have spawned a relentless and exhausting Rebecca vs. Rebecca debate: are these normal-person feelings, or crazy-person moods? There are moments when I think that my friend could use a little Mad Pride; other times, I wish I could force medication down her throat. There are also moments where I wonder, Where’s the parade for witnesses?

I return to the Shaughnessy, because despite my ambivalence, there’s something in the fuck-you attitude I find compelling. “People often ask, what are the alternatives...to despair?” he writes. “To me, it’s quite simple. How would you like to be treated? As an object, or with dignity?” I understand this. There is no recovery without addressing the profound alienation of stigma. But at the same time, it seems a dangerous mistake to lose sight of the brutal effects of the symptoms themselves. Those inscriptions on the asylum wall—I wonder how many of their writers were beaten down from daily abuse and indifference, and how many were in the grip of psychosis; sick.

As I was finishing this article, Rebecca called me. She wanted to give me a “heads up” about her “shaky mood,” though she sounds OK on the phone—a bit rushed, but OK. “Let me know about your article,” she says. “I want to help you with this, but I’m feeling a little crazy. I may have to disappear for a while.”

--

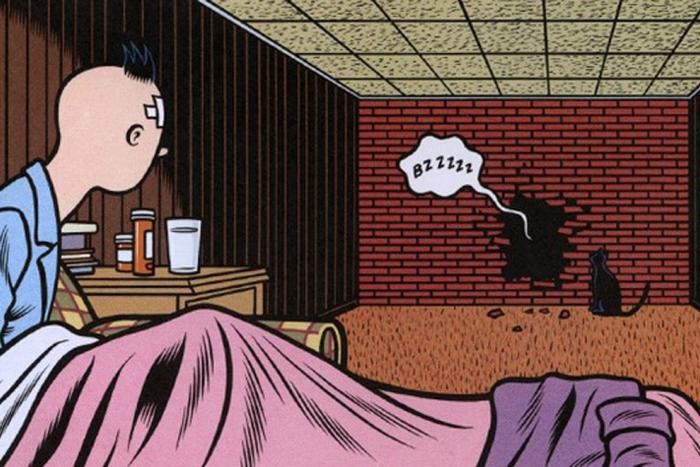

Photo by Tyler Anderson