In January 2015, Mandy Len Catron wrote an essay for the New York Times about falling in love with an acquaintance using a 20-year-old psychology experiment. Participants answer 36 personal questions and then stare into each other’s eyes for four minutes. Or at least that’s the short version of the story that went viral. By the end of 2015, it was one of the NYT’s most read stories of the year. Catron’s love life became public knowledge, with strangers nosily inquiring if she and the man she’d written about were still together, if they’re going to get married and have kids.

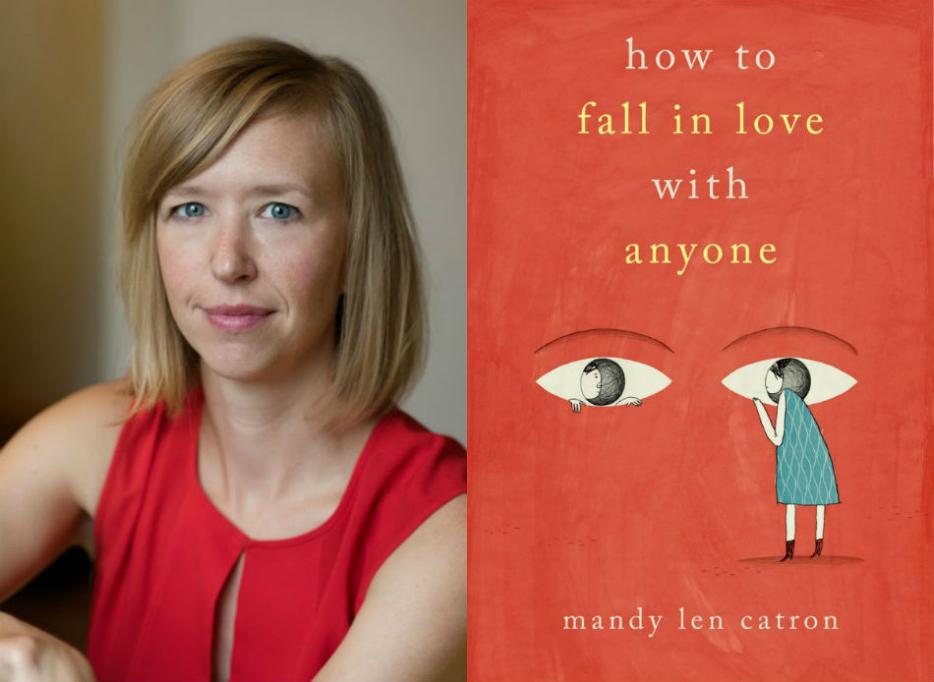

Catron understands why people ask for the simplified account—people want neat and tidy romantic fables where love plays out in predictable ways. The longer version of the story, which Catron details in her debut book, How to Fall in Love with Anyone (Simon & Schuster), actually happens over the course of a few years and is much more complicated than she had word count to outline in the original piece.

Told through a series of personal essays, Catron explores her own perceptions of love and how they were shaped by her childhood in Appalachian Virginia, her parents’ divorce, the ending of a 10-year relationship with her college boyfriend, and witnessing her own love story go viral. She supplements these introspective musings with references to scientific studies, academic papers and romantic comedies to investigate how societal norms and pop culture affect our views of love.

Catron teaches English and creative writing at the University of British Columbia, is the author of Mixed Feelings, a new column at The Rumpus where she doles out evidence-based relationship advice, and continues to dissect love on her own blog, The Love Story Project.

Samantha Edwards: What’s your first, favourite love story you remember from your childhood?

Mandy Len Catron: When I was young, there were probably several examples because I was super into love stories as a child. I really loved the movie Sleeping Beauty. I watched all the Disney princess movies like everyone else did. So it’s either Sleeping Beauty or my parents’ love story, which I remember knowing from a very early point in my life.

Sleeping Beauty was also the first Disney movie I loved growing up. I remember renting it constantly from the local video store. Do you remember what you liked about it?

Oh my gosh, it’s so disturbing to think about now. Of all the princesses, she’s probably the most passive. The story happened while she was asleep! I have no idea why that movie spoke to me; the messages in that movie are especially problematic for little girls.

You write about how growing up, you’d tell all your friends the story of how your parents met. Your dad was the football coach and PE teacher; your mom was the cheerleader. What did you love about their story?

I think part of it was that their story implied this sense of fate, or destiny, or momentum that brought them together. I loved the detail when I was a kid that my mom initially set my dad up with her older sister, and then my aunt ended up marrying my dad’s best friend, and then they all had this double wedding. It just felt like the kind of story you could see in a movie. I think as a kid, it gave me this real sense of security and belonging.

When did you start getting obsessed with love stories? Was it after your parents’ divorce or all throughout your childhood?

I’ve always been into love stories, but I think my parents’ divorce was the inciting incident that made me want to step back and think more critically about the narratives we consume. I’m an English teacher, so I think a lot about how stories influence the way we think about the world. Also, just as a person, I think I felt a little anxiety about love, so I wanted to take this thing that made me feel anxious and see if I could think about it a little more clinically and see exactly what was going on there.

And throughout the book, you mention a lot of studies or academic papers about the science of love, where you’re looking at love through this outsider’s perspective. Reading all of this stuff, did it help you make sense of your own relationship with your ex-boyfriend?

It did, but a lot of that happened retrospectively. As we were breaking up, which was a year-long process, I found it so reassuring to read the science, the biology of heartbreak, which made me feel that while this is awful, it’s awful for everyone, and that awful-ness is predictable and normal.

Was there anything in particular you found especially reassuring?

I had this huge fear before we ended that relationship that I would just never, ever meet anyone I loved the way I loved him. During that period, I read the study about Arthur Aron’s 36 questions and I remember thinking, oh, maybe it’s just science. Maybe it’s as simple as creating this experience in your brain. I was very skeptical of the study, but it did make me feel like love was this really ordinary experience, it’s normal and pedestrian, even though it feels quite profound, magical and mysterious. I think I just needed to know that: It’s not like I was giving up my only chance at ever finding love.

I think when you’re breaking up with someone, it’s easy to think, “Maybe this is ‘The One’ and I’m making a mistake” and then in retrospect you realize, like, oh no, no, I made the right decision to end that. I don’t think you can just follow your gut. I feel like our guts are often really wrong.

Yes! They are! I wish we talked about this more. There’s this sense that gut feelings are good and reliable, but when you explore the neurochemistry of love and the way it acts in your brain and the effects it has on our emotional states, it’s like, oh, actually, this isn’t a reliable mode of decision making at all.

I remember reading your Modern Love column and, right after, telling my boyfriend, “We should answer these 36 questions and then stare into each other’s eyes for four minutes!” Then there’s the moment you describe when you and Mark are at restaurant and you hear the couple at the table next to yours going through the questions. After the essay went viral, what kind of reactions did you get from people?

What was interesting about that experience was that after having written about love stories for all these years, and then suddenly seeing my own relationship become the kind of story that I didn’t quite believe in. Right after the essay came out, strangers would say, “I have to ask…are you guys still together?” and when I would say yes, and they’d be like, “Oh my god, that’s amazing.” And I just thought, you know, all they want is to feel like this thing works. Nobody wants to talk about the quality of the relationship or how going through this experience impacted the way we interact. “Are you together? Great!”

What did you learn about yourself during the writing process?

I think the biggest thing I realized was the authority that the normative script of love had in my life, and I think in most of our lives. These scripts for how love should shape our lives, they’re so powerful, I think they’re almost invisible.

A lot of folks call this the “relationship escalator,” this idea that you unthinkingly move from casual dating, to exclusivity, to co-habitation, to marriage, to buying a house and to having kids. So many of us do that because that’s prescribed by our culture. The thing that I got out of the years of research more than anything else was realizing I can have a good life even if it doesn’t match that narrative. I feel a lot more empowered to create the kind of relationship that works for me and my partner, rather than just sort of following the predetermined script. And when you start pursuing more diverse stories of love, [you realize] there are lots of different ways that love can shape a life.

Are there any movies or TV shows you’ve seen recently that do a good job of going off-script?

I really love Aziz Ansari’s Master of None. I think why it’s so great is that he’s done the research. He wrote his book, Modern Romance, with sociologist Eric Klinenberg. He was using his stand-up shows as venues for doing focus groups on, like, how to date and what works and what doesn’t. On the show, he rejects a lot of these tropes that feel really familiar to us. In the [season finale] in the first season, Aziz and his girlfriend are at a wedding together and as they’re watching the couple get married, you hear their own internal monologues: “Oh my god, why don’t I feel this way about my partner?”, “Does this mean our relationship is bad?” Nobody talks about that feeling, but so many people have it.

When I think about current politics, climate change and everything that’s happening in the world, in some ways, the idea of love stories feels like such a quaint concept. When you were writing this book, did you ever doubt the importance of love?

There’s been times, especially in the past year, where I’ve thought, oh my god, this feels so trivial compared to like, basic human rights, which I felt were constantly being jeopardized thanks to a lot of political changes. The more I think about love and love stories though, the more I’m like, everything is political. The way we think about love is often connected to things like basic human rights. Our love stories influence who we think is allowed to experience love. I think the proliferation of more stories about people who are queer or consensually non-monogamous, the more we’re able to think, “I actually have a lot in common with that person” and acknowledge their fundamental humanity.

It is so important that we consume media about different love stories, whether it’s a polyamorous, interracial or queer love stories.

I think going in I had this idea that the real problem was the power of heteronormative love stories and how they were closing everyone else out. Our stories were very much about attractive, thin, white straight people who were married or heading towards marriage. I thought, “I’m going to write about these stories because they’re the problems.” I realized pretty quickly that that’s wrong. Lots of love stories, even queer love stories or less normative ones, are still problematic. So many love stories really fetishize love as the most profound, meaningful experience you’re going to have in your entire life. For plenty of people, there are other parts of their lives that are more profound.

You devote a chapter to breaking down Cinderella and Pretty Woman, and the connection between love and deservingness, which I had never thought about before. This idea that if you’re not in love, then there’s something inherently bad or wrong about you.

It’s ridiculous and I think it’s very much related to the stigma of being single in our society. It’s so hard for people to acknowledge that someone might enjoy being single. Amatonormativity, which comes from the philosopher Elizabeth Blake, is this idea that we’re all happier, more full-filled and better off in a long-term, committed, monogamous relationship. If we could let that go, people might be more able to practice love in the way that we’d all benefit from.

I think the emphasis on deservingness and goodness is really so gendered. What it means to be lovable if you’re a woman is so different from what it means to deserve love if you’re a man. There was a study that showed women who have implicit romantic fantasies show less ambition, less personal power and less desire for achievement, and that they tend to conceptualize achievement as something they’ll do through a romantic relationship, like through a man. If you let that sink in, it’s so disturbing and yet I think I was exactly that kind of 19-year-old. I think I probably conceptualized myself as someone who was very independent and yet when I look at my relationship at the time, I thought my ex-boyfriend Kevin was so interesting, that if I attached myself to him, then people will know I’m interesting. It didn’t occur to me to just become interesting, which is so awful.

Do you think these ideas are specific to women?

Yes, absolutely. To deserve love as a woman, you need to be “good,” and the women who are rewarded with love in most stories that dominate the mainstream are obedient, meek, mild, sweet, cute, small and frail. They have this very conventional, feminine vulnerability. Even Julia Roberts’s character in Pretty Woman, she’s obviously sort of sex positive in a way that seems radical in 2017, and yet at the same time, there’s the scene where Richard Gere’s character thinks she’d doing drugs in the bathroom and she’s just flossing her teeth. It’s like, oh, actually she’s naïve, young and good. She’s a perfect partner for this powerful man because her whole contribution to their relationship is helping him loosen up and be his best self, but there is no self-actualization on her part. Her presumed role in the future of their relationship is just to make him better.

I have a theory that the RomComs you liked when you were young are a good indication of how you perceived yourself. I always loved Never Been Kissed with Drew Barrymore because I was an aspiring writer and kind of dorky looking, like Drew Barrymore’s character [pre-mandatory makeover]. I liked how in the end, she got the handsome guy who liked her for her intelligence. What was your favourite growing up?

There were a bunch of them, but I think the one I saw myself in was 10 Things I Hate About You. I think it was the same thing: Julia Stiles’s character was smart and self-possessed, and she knew who she was and what she wanted. I just loved her character. She found somebody who was like the perfect match for her. I think that movie came out in when I was 16 or 17 and I remember going to the drive-in movie theater with a bunch of my girlfriends, and we all loved it. We were the sort of girls who didn’t have a lot of boyfriends, we weren’t particularly popular, but we were good at school and we loved Shakespeare. We were like, yes! This is the sort of teen fantasy for us.

Does it hold up now?

I haven’t seen it in a long time, but I’d say a little bit. There’s this rape culture subplot that I feel like would be hard to pull off now without making it a little more explicit about consent. But Julia Stiles’ character, I still think she’s pretty awesome.

You write about how when you were young, you imagined yourself being married at 25 and then having your first kid at 27. I wonder if young girls today imagine their timelines with similar ages, or if everything’s pushed back now.

That’s an interesting question. I wish someone would do a study on this. My instinct is on the whole, they don’t imagine their lives the same way because they have more models. The average age of marriage is the highest it’s ever been for men and women. When I talk to my first-year students at UBC, they’re much less interested in marriage than I was at their age. I think there are a variety reasons for that, one of which is economics. Thanks to the recession and housing crisis, people want to establish their careers, be debt-free and in a good financial position before they get married. But I also think that while marriage is obviously still a very important part of our culture, thanks to a variety of social forces, one of which is the most recent wave of feminism, young women feel like there are lots of modes of finding validation and having their humanity affirmed beyond getting married.