I found the first dead hen a week before the full moon. She was lying in the corner of the wooden coop, neck splayed and eyes shut, while the other hens stepped around her like dashboard bobbleheads. Because I had been responsible for her, the death felt like both tragedy and failure. I’m sorry, I thought, standing above her body, and then I remembered it was a new year, and I was trying to stop apologizing for things that were not my fault.

Rolling the hen onto a snow shovel, I trudged to the compost heap. The path was pockmarked with icy footprints, and holding the shovel in front of me, I felt like a cartoon baker delivering a pizza to an oven. Fresh snow had made a

Alone with the pines and stars it felt like the right moment to thank her, so as I stamped my feet for warmth, I thought of all the eggs I had fried and baked and poached to wobble above my salads like storybook clouds. Was this one of the hens that had pecked my hand or plucked feathers from the pink rump of another? It didn’t matter. As snowflakes sifted around us, she turned whiter and whiter. In the trees I heard an animal, and I wondered.

Hours later, after I’d coaxed a fire from the woodstove and opened and closed my book, my heart still flopped like a fish on a dock. How hard, how easy, to let a body go.

*

A few months earlier, I had driven a car full of books and sweaters to a New York artist residency on a farm so far upstate that I learned, upon arriving, it was not even called upstate. Welcome to the North Country, said the tired man who rang up my dried pasta in the nearby grocery store. When the holidays came, and the staff and other long-term residents left, I accepted an offer to stay and help with upkeep. I had recently moved away from a city that I loved, finishing graduate school and severing a long-term relationship around the same time. The whiplash of transition had left me perplexed about the form of my life,

*

I had imagined myself growing old beside my graduate school boyfriend. The few years we dated signified the longest relationship either of us had been in, and the first where I felt the boundaries of myself dissolve. We met soon after I moved to the Midwest for my master’s degree. Unsure how someone could feel both deeply familiar and wonderfully foreign, I threw myself into solving the puzzle. Within a few weeks of our first kiss, the man and I began spending almost every night together, buying groceries to stock the fridge I shared with my roommates and going for runs in the park. It was easy to suppress the anxiety I felt about my shrinking alone time. I didn’t want to be a commitment-phobe: I wanted to learn how to show up for another human, day after day. The man was easy to show up for. He brought me clumps of orange lilies on random January days. He entertained my visiting family when I overbooked myself, drove me to appointments when I was running late, and helped me parse the minutiae of the sentences I struggled to write. We called one other if we eavesdropped something juicy on the bus, or saw the pet pig leashed outside the co-op, or if one of us had a revelation about the revisionist glory of mainstream biopics. How easy it was, to live like mittens on a string.

Both of us wanted more quiet space for work, so when, six months into dating, a spacious-but-affordable apartment opened up beneath mine, moving in seemed like an obvious choice. After years of hearing

If our relationship was a sun-dappled two-way street, our main problem was speeding too fast down it. We never told each other “no.” I wrote to-do lists for him, researched travel plans and potential jobs for him, bought him a new coat and a new backpack, helped him draft tricky texts and emails.

I was so committed to mapping the shape of the man’s potential wishes—and so comforted as he tried to do the same for me—that I learned to ignore the doubt that lapped at my ankles, a wave that rose every time I kissed him goodbye, left town for work or travel, and remembered, with a shock, how happily whole I felt alone.

*

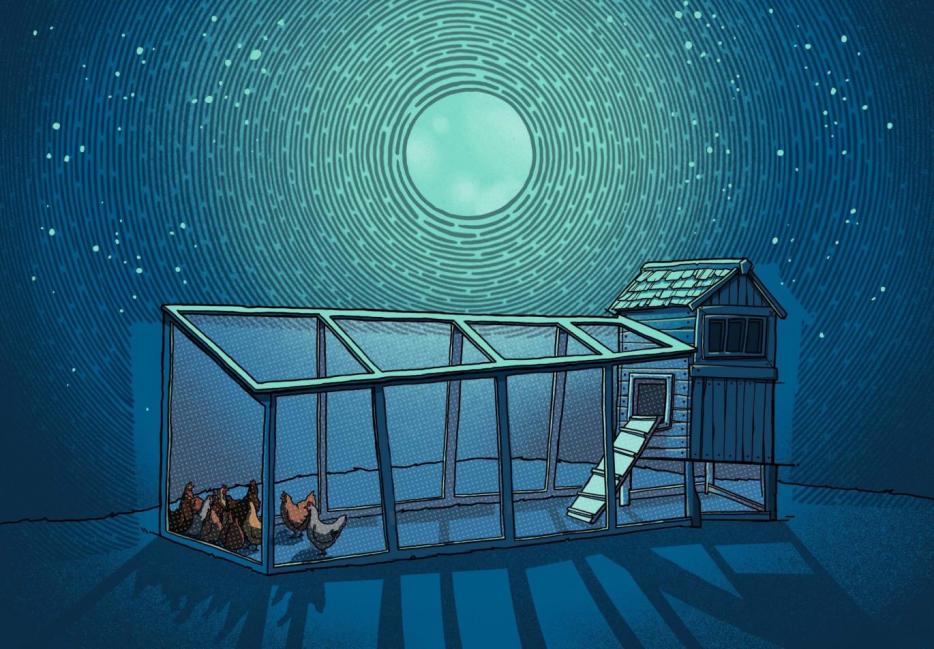

On the farm, I scaffolded my days around the animals. On warmer mornings, I’d let the chickens out of the henhouse and into a large, fenced pen, where they’d peck for bugs amidst brown grass and trampled snow. Around sunset, I’d shoo them inside. Many walked into the coop on their own, but I’d always have to chase a few down. In those moments I’d think of my childhood dog, a neurotic shepherd who ran up and down the hiking trail, barking as she tried to nudge us together. Her self-worth depended on our security. Worrying, my mother often reminds me, is another way of saying I care. The word “care” is rooted etymologically in an Old English term for sorrow and grief; it is an act of service that acknowledges the inevitability of mortal loss. In this way, caretaking is always consolation, not just for the other—Life is short but I am here for you—but for the self. Life is short but I am making the most of it.

In the absence of farm animals, our dog took to herding humans. Now, in the absence of other humans, I was herding animals. It made me wonder if caretaking was just another form of mass. Maybe it could not be created or destroyed, only displaced. When I filled the food bucket, and the chickens bobbed their heads at me expectantly, I felt a rush of self-actualization. It was a relief to have others depend on me again. I did not know how else to repay the gift of having a body.

Though I treated the chickens as equals, I indulged grudges, too. When I glared at the rooster, I wondered if I should feel bad for resenting him. Industrial poultry farms put male chicks in giant metal grinders. Should that alone make me empathetic to this bird, tall and white as a scraggly swan? He seemed to spend much of his time clambering behind a seemingly oblivious hen to mount her. The ritual only lasted a few seconds, the hen squatting with her wings splayed as if preparing for battle. More than once, though, the rooster would finish not by flapping away, but by lifting his turmeric-coloured talons to stand on her. The hen, in these moments, was frozen. As if she had accepted her role as a rock in a rising tide.

*

The night before the man interviewed for a job that would move us across the country, I lay awake wondering how I might have helped him prepare better. I had often felt nauseated by my own ambition—an anxious twitch that made me throw myself in near-constant strategizing for the road ahead—and brainstorming my partner’s future felt like a virtuous reprieve from my own. I knew our love was good fortune, but it also could feel like a large debt. Overwhelmed by his generosity, I’d rush to prove myself worthy, never pausing to wonder if I could just be. I’d coordinate our travel plans, orchestrate our social calendar, and text him suggestions of things to read, to write, to buy. I delivered the attention like a cat with a dead songbird at the stoop. Take this. It means I love you. He always did.

*

One day when I was bent over collecting eggs, a hen launched at me from the roosting ladder. The hand I raised to protect my face met her body, and she flapped away, squawking. Aware that my heart was pounding with something like betrayal, I suddenly saw myself as she might have: a predator elbow-deep in the lay box, hoarding someone else’s would-be kids, no better than a python.

Unlike the relationship I once had with the family shepherd, any symbiotic relationship between the chickens and I

Every day the chickens laid nearly forty eggs, and every day I ate one or two, and stacked the rest in cartons at the self-serve farm-store. With so many people gone for the holidays, my task began to feel like a very fragile, high-stakes Jenga game. What are the best ways to use an egg when you are drowning in them? People pickled them in beet juice and split them into meringues and whiskey sours and sucked them raw for hangovers and ran them over their naked bodies for spiritual cleansing. I once cracked one on my head, having read it would provide gloss for my unruly hair, but it hardened like the glaze on fresh challah. When I tried to wash it out, the too-hot shower baked white strings into the tips of my curls.

One night I tried to sneak in as many eggs as I could while making carbonara for a neighbouring potter. Mmm, he said, spearing a clump of thick yellow pasta with his fork. I think he liked it, but I was the only one to go for seconds. I could not forget what the chicken had done for us. I did not want to be hated by anyone, especially a hen.

*

When the man was offered the new job, I felt as excited as if the offer had come to me. Finally, we were going to have real money! We were going to move to a big coastal city! But in the months when he left to nest our new apartment and I stayed to wrap up ends in our old one, I was surprised how much I loved living alone. At night the man would tell me over the phone how much he missed me, and I echoed his words, but I didn’t always trust them in my throat.

For years I had failed to draw boundaries around my own energy, muffling the

Meanwhile, in the cracks of my subconscious, I wondered what would happen if I rewired my frantic future-planning energy back toward myself. I was having such fun living alone for the first time in my life, in a city of people and restaurants and lakes that I loved, and one day I realized just how much would still be here for me if I stayed. The thought was devastating and terrifying all at once. Because I did not know how to make room in a relationship for my own want, it felt easier to sidestep the possibility of new wants entirely. I told myself I had often gotten the yips during big life transitions. I packed up our moving pod. I joined the man in our new city.

*

The closest living relative to a Tyrannosaurus rex is not the crocodile scientists once envisioned but the family of birds that includes the farmyard chicken. I remembered this one morning when a bird jumped on the lip of my plastic egg bucket and toppled it on its side. I heard the cracking before I saw what had happened: two sea-foam-coloured eggs rolled onto the ground, golden innards oozing out on a fresh layer of sawdust. Within seconds, every hen in a two-foot radius had pounced and started pecking. Maybe peck is the wrong word.

I wondered if the chickens somehow knew, that powdered eggshells could serve as a digestible calcium supplement. Strange people on the internet sprinkled them in soups and baked goods, and I had even seen a recipe for dissolving the shells between layers of fermenting sauerkraut. Were the chickens now driven by minerals or cannibalism? I wanted to believe that they knew destroying something you had made could kindle a strange confidence. It forced you to acknowledge that one day—surely—you’d be able to make the thing again.

*

By the time I knew I needed a different path, too much time had passed. We had scouted Saturday estate sales for midcentury coffee tables, and more than once, I had let myself cry in the bathroom of a Tudor mansion before wiping my face, stretching it into a smile, and helping load our car. We told all our old friends and new neighbours that this was it: our newborn life. The whole time I kept flattened cardboard boxes hidden in the back of my closet, wondering if I would have the courage to fill them back up.

When I eventually ejected myself, a few months later, I did it in the worst way possible. I let myself respond to texts I was receiving from someone else, someone I had little in common with, the man’s polar opposite.

*

Winter in the Adirondacks was dry, and because I kept touching chicken shit, I was washing my hands more vigorously than usual. I began to find in both the eggs and my hands the places where smooth freckles morphed into dry bumps, and nicks fissured and hardened. Every day when I scrubbed the eggs with dish soap and hot water I marveled at how a cracked egg could maintain its whole. The eggs that froze overnight would crack into spiderwebs so delicate they might have been drawn with a newly sharpened pencil. These were “farmers’ eggs,” and I carried them home for lunch and split them in the pan, where the yolk rolled like a pool ball into the cast-iron, a perfect orange orb.

An egg is stronger than we give it credit for. A chip in the shell does not mean collapse, just a peep at the membrane beneath. If at first I thought my scraped knuckles looked terrible, a closer look revealed a new world beneath, something softer, brighter, more surprising. An egg is a song of structural dignity. Go ahead: squeeze it. An egg cannot be crushed by one hand alone.

*

Toward the end of my holiday chore stint, I took a bus to New York City for the weekend. One afternoon my sister and I saw a retrospective for Sarah Lucas, the contemporary British artist renowned for her commentaries on gender, death, and sexuality. We walked into a large white room full of beautiful people trying to hold their faces in serious expressions as they sidestepped a torpedo-sized penis pointing toward a half-torched car ribbed in unlit cigarettes. The wall behind the display was covered in a supersized photograph of a naked torso in white underpants, a raw, oven-ready chicken splayed across the crotch, the cavity of its neck a gaping hole.

In the next room, a work called One Thousand Eggs showed the streaky aftermath of many yolks tossed against a white wall, their brown shells accumulated at the base. A plaque told me 1,000 women had been invited to throw eggs in the gallery. I wondered what those women had felt: if the piece was a meditation on women seizing control of their own reproductive rights, or, as The New York Times suggested, “an act perhaps envisioned as female ejaculations.” I liked seeing the eggs as political, not just 1,000 foiled breakfasts. In another room, a glass case held a small carton filled with half a dozen white plaster eggs. Each egg held a letter: F-U-T-U-R-E.

Later, a friend told me he always thought a row of eggs was like a row of ellipses. It was true. An egg is raw material; it is possibility in your palm. Especially if it is fertilized, an egg can become many things. Beneath the smooth stone of its shell is a little sun cased in white. Some folk songs literally refer to the sun as an egg. Sun, dear sun, a divine egg! sing Bulgarian children. Man is a chicken brooded from you and shown to the world! Each yolk is a single cell, one of the world’s largest. Just like a sun, a cell is a building block of life. You cannot see an egg without seeing a new beginning.

*

I found the last dead chicken the week of the polar vortex. With everyone back from the holidays, we had resumed our rotating chore shifts. After a month of quiet mornings, I was on duty for a final week before leaving the residency. The windchill was in the negative double-digits, and walking to the birds I felt the tingling progression of my numbing fingers through my ski gloves. Inside the coop, the heated, hanging water tank was solid ice, and the ammonia smell of chicken urine was muted, as if the air was too busy being cold to hold a stink. I had already topped off the grain and started searching for eggs when I saw her in the corner of the coop. She looked like a rubber chicken, long and slack, without the breathy chest-puff of a cartoon hen. Shit, I thought. Not again.

After the first death—and then one more, which another resident found—the head farmer had mused that maybe an illness was going around. She had not wanted us to panic, because there was very

Outside the coop, the wind slapped my face. I did not want to drop the hen, but it was hard to hold the swaying shovel straight in front of me. It was easier to move through the calf-deep snow if I clutched her to my chest, shielding her with my body.

At the compost, I rolled her onto the heap of snow. The sun was bright, like the incubation lamps farmers used to keep young chicks alive. For a minute, I felt guilty that I could not summon the raw sadness that had bubbled up for the first bird. Instead, I felt calm. My winter of coexistence with the chickens had come in a Tetris of circumstance and choice, the same elements that had now, in some form, taken her away.