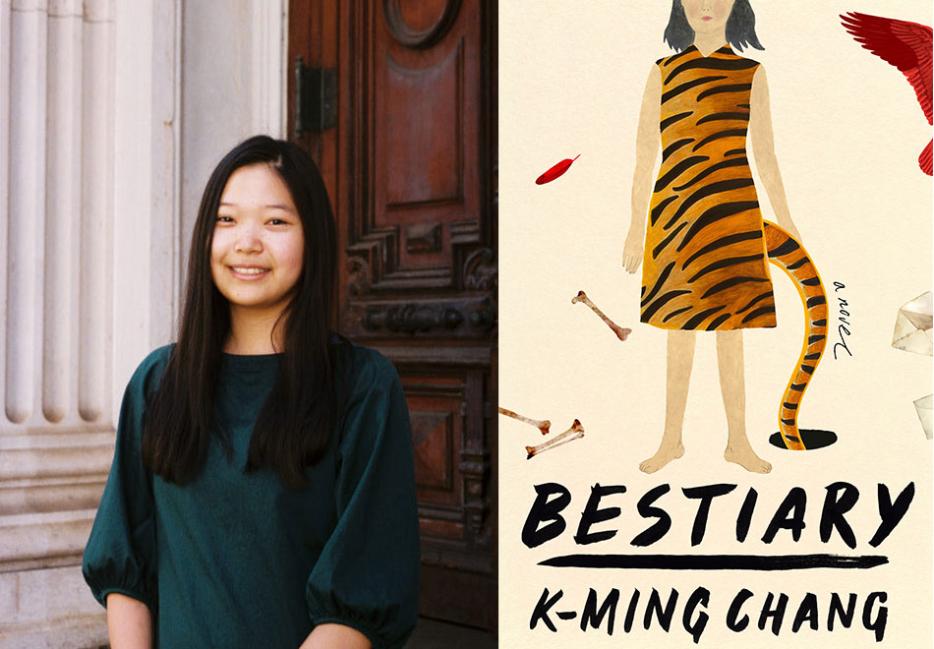

K-Ming Chang was born in the year of the tiger. According to the zodiac, tigers have a strong sense of justice and resist being held back by rules. An unwillingness to be disciplined. This speaks to the spirit in which her debut novel, Bestiary (Hamish Hamilton), unfolds: vivid, thrilling prose-poetry that traces the lineage of three generations of women wrestling with their Taiwanese heritage. The present-day protagonist, Daughter, is raised on a diet of spoken legends and folklore passed down by her mother. One of these myths includes the Fujianese/Taiwanese myth of Hu Gu Po, a tiger woman who eats the toes of children and calls it “snacking on peanuts.”

It’s not long before the myths seep into and corrupt the rhythms of everyday life: Daughter soon grows a tiger tail from an inflicted wound on her back, starts to fall in love with a classmate, and begins a larger-than-life project of translating her grandmother’s handwritten letters and coming to terms with who her history belongs to.

The imagery of Chang’s novel is enchanting, hypnotic, a burst-of-energy, up-in-arms kind of nostalgia-induced nausea: the seams of pillows splitting when bitten into; geese rotting in reverse; uneaten jars of baby food; salty fishdaughters with sequin scales; landscape paintings visible in underwear; suns sagging in the sky; spit dyed with fruit; fog that looks like whisked eggs; sweat that smells like sweet pudding. It’s a soupy, escapist world that welcomes forgetting a sense of control or normalcy.

Over email, I spoke with Chang about how she practices self-care, writing Emily Brontë fan fiction, and returning to childhood diaries as a source of inspiration for novel-writing.

Nathania Gilson: A pattern I saw woven through Bestiary is the tradition of oral storytelling carried through three generations of family members, across cultures, borders, and time. What were your own experiences of growing up around other peoples’ stories? And how did you learn to interpret voices and gestures on the page?

K-Ming Chang: The tradition of oral storytelling is deeply important to me. Because of barriers to literacy, oral stories were often used as the primary way of recording history and myth. They were also incredibly funny, dark, winding, and strange. When I was a child, I was most interested in stories about me—I was very narcissistic!—and I also listened devoutly to stories that felt like allegories for my life. When I was little, I only listened peripherally to stories that were about generations of my family and war and women, but as I grew older, I realized that my desire to tell stories was intimately connected to the oral tradition’s embodied-ness, and the sense of freedom and flexibility that comes with when a story is detached from an authoritative text.

I grew up listening to others’ stories, and listening to people narrate lives that were not their own, so I loved writing effaced first-person narrators and observers and witnesses. I always felt like a witness: watching, waiting to intervene. The way I interpreted voice and gesture was to center the body on the page, to continually remind the reader that the story is coming from a body; a mouth. It’s being performed.

Something else that comes up in the novel is the queering of mythology through mishearing. The narrator, Daughter, listens to her sibling Jie talk about two girl ghosts kissing in (cleaning) the creek. In your research (living, reading, connecting the dots between historical events and present day), did you come across anything that sparked new ways of thinking about how legends, myths, and superstitions become a way for people to write themselves—or their experiences—into existence?

Yes, absolutely! I think so much about queerness is about myth-making, inventing a story and a future for yourself. Queerness is an act of imagining. I think that people often think of myths and folklore as a thing “of the past.” But folklore, to me, has always been about futurity. Myths are about world-making, and so is imagining the future: imagination is a tool and a weapon that allows us to tear down and rebuild. Similarly, the mythic voice and mythic scope of storytelling allows me as a writer to reimagine the world; to probe possibility. For the characters in the book, harnessing myth and redefining it is tremendously powerful, akin to transforming the rules of their reality.

Feces, vomit, spit, farting, and blood are ever-present in Bestiary. What was the choice behind mentioning the grosser details of being alive?

This is definitely something I only became aware of after people started reading the book and commenting on its grossness, which I really appreciated—I wasn’t able to see it myself!

I think that it’s very natural in my family and with the people I’m intimate with to discuss the body and excrement in a shameless way. That these boundaries of what’s proper often break down when we’re with the people closest to us. The characters in Bestiary are extremely intimate and close-knit, and because of class, they’re also not able to separate themselves from the shit of the world, because they literally have to work in proximity to it, like how the mother character works at the chicken farm and scrapes poop from the floor.

I also wanted to entwine the “grossness” of life with beauty and associate it with intimacy and closeness rather than with shame and disgust and distance. I think our first instinct is to always distance ourselves from things we’re ashamed of, and in Bestiary, I think the characters resist shame and dissociation, and instead feel deeply attuned to their bodies.

One of my favourite things about the book was watching Daughter become friends with Ben. And seeing their mutual desire and admiration for one another grow into something bigger. A bond forms between them through the act of translating Daughter’s Grandmother’s letters. Were there any examples of female friendships or romances in literature or popular culture that you looked to, that either lit a spark or gave shape to this one?

I’m so glad that you mentioned Ben and Daughter, because they were such a joy for me to write! I think that rather than looking to examples of friendships between girls in literature, I drew more from experience.

I recently re-read my childhood diaries and was swept away by the intensity of what I felt for my friends growing up, and how love and affection was also deeply entwined with violence and explosiveness.

There was both volatility and a sense of permanence, that we would be together forever and name our children after each other.

I loved the grand, whole-heartedness of those statements, and similarly, with Ben and Daughter, there’s an almost supernatural attraction between them. I wanted it to be grandiose, bordering on ridiculous, to risk sentimentality, to not hold back. I imagined them as partners in crime, but also as each other’s spiritual and emotional guides.

Bestiary has multiple gods. Grammar becomes “the god of language,” Daughter’s father is “the god of water.” It made me think of the tendency to put things, or people, on pedestals as children because we see potential in them that we might not see in ourselves. Then again, Daughter frames god as the opposite of karma. I wonder how much you were thinking about spirituality while writing this novel?

I was thinking a lot about spirituality and the divine, but as something plural and multi-faceted rather than singular. Daughter has internalized all these different religious influences and gods, and I think what remains consistent is the presence of fate and her persistent feeling that not everything is within her power to control.

I also think that the godliness of the other characters was both reverent and also a little irreverent. So many people, especially very morally complicated people—like the father—have elements of godliness, and there are so many forms of power that Daughter witnesses. I think that all the religious and spiritual influences are deliberately muddled and blended—they’re all inheritances, and Daughter is parsing out what she wants to believe in.

You are a prolific writer of poetry and prose. Bestiary manages not to choose or side with one or the other. Do you ever feel pressured to switch between the two forms, or work harder to make the two ways of approaching narrative cooperate on the page?

I wish I were more experimental and better at blending the two! I definitely want to continue experimenting with the ways prose and poetry cross-germinate. Because I’m so focused on individual words and phrases, which is an obsession and process that carries into both poetry and prose, I feel immersed in the same way no matter what form I’m working with. I definitely do feel pressure to return to poetry, but currently, I’m still playing around with prose, and I have to remind myself that I can always move between them!

In this book, Daughter works out what it means to change your own destiny. How do you think being a writer has changed yours?

It’s changed my destiny entirely. I’m so grateful for the people who have believed in my writing and invested so deeply into it, even when I couldn’t imagine my own future as a writer and still struggle to do so.

I think one thing I didn’t anticipate was that writing has brought me closer to my own community and has transformed me internally and allowed me to confront my history, personal and collective.

The red-inked feedback that Daughter and Ben receive in class, found in the margins of their essays, cracked me up. “Improve your grammar. Improve your spelling. Implore your gods. We’ll show you a sentence.” It reminded me of how often people who are new to a country are underestimated. In a world that wants everyone to make sense, how does poetry allow you to look beyond that?

I think this is tied to Ben being the god of grammar—Daughter sees Ben’s mistakes not as mistakes but as the godly invention of a new language. Poetry, for me, allows for rupture and invention. Rather than language that is grammatical or “correct,” it prizes innovation, and those outside of the language are the best at innovating it; seeing its possibilities, breaking and reinventing it. Poetry gave me permission to be playful with language, rather than having a punitive relationship with it—we often punish language play and innovation rather than nurturing or encouraging it, and poetry feels like a much-needed realm of transformation and possibility.

You have a chapbook, Bone House, forthcoming in 2021. It’s been described as “a queer Taiwanese-American micro-retelling of Wuthering Heights.” Where did your interest in Emily Brontë come from? What does Romanticism fail to do, that you hope to explore in your interpretation of the work?

I could talk about Wuthering Heights forever! Bone House truly is my work of Brontë fan fiction. My interest in Wuthering Heights actually came from the novel being mentioned in the Twilight books, which I read in middle school.

After reading Wuthering Heights, I remember thinking to myself, “This is so Asian!” It reminded me of a lot of Chinese soap operas: the repetitive generations, the ghost story, the haunting, the grand declarations, the innocent bystanders and slanted storytelling and various voices.

I loved how convoluted it was, and how it was unexpectedly a multi-generational epic. I’m not totally sure what it fails to do, but I think the one thing that continually interested me is that Heathcliff is orientalized in the original novel, described as darker-skinned and other, even speculated to be from India or China. I was interested in this orientalizing Heathcliff as a “wild” and untamed other, and wanted to lean into those references and dynamics and explore how they play out in the Taiwanese-American community.