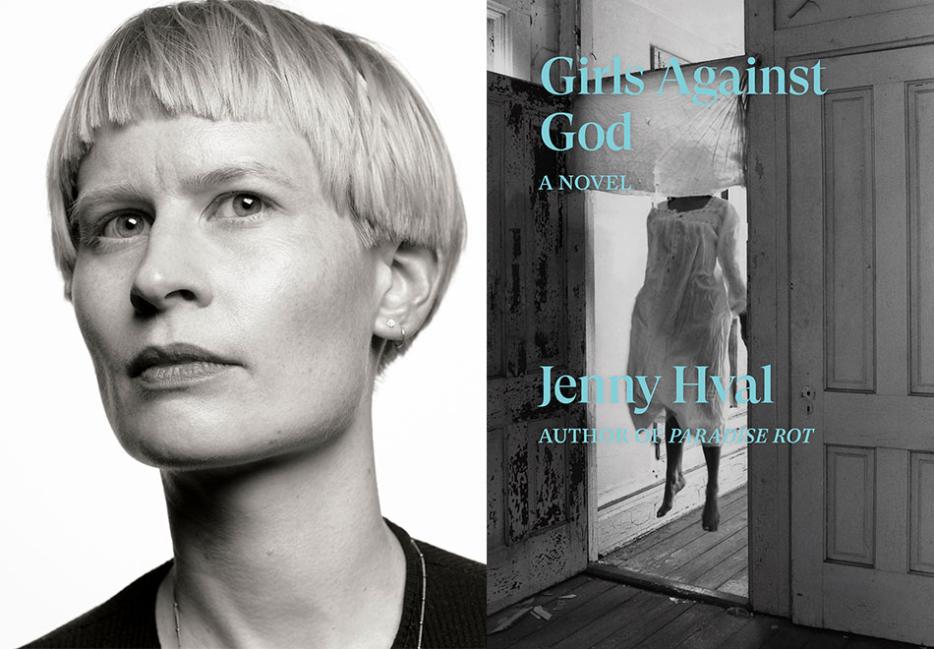

Jenny Hval’s third novel, Girls Against God (Verso), rejects capitalism, the patriarchy, and oppression. Through non-linear, stream-of-consciousness-style vignettes, an unnamed narrator lives through a difficult childhood in 1990s Norway, grows up and travels to study in America, and comes back to Oslo to start a black metal band and write a film.

Originally published as Å hate Gud (To Hate God) in 2018, Marjam Idriss’s English translation highlights an early obsession with hatred that evolves into figuring out how to turn it into something useful. “I remember how much hope there is in hatred,” points out the unnamed narrator.

By the end of the novel, the boundaries between what we consider to be reality and understand to be part of a film blur. In Hval’s world, bands are transgressive communities; it’s a place where the potential for witchcraft lies dormant in all women; and God (in the novel, less a religious icon and more of a straight-talking presence that looks after the exploited) is “always in the systems, in the sewers, in the trash, in the garbage.”

In the tradition of American experimental novelist Kathy Acker, Hval’s writing embraces finding new ways to express thought patterns, experiences, and stories—and encourages people to let go of logic rather than look for the familiar markers of institutionally accepted creative writing.

Over email, I spoke with Hval about the joy of admitting to liking things, what it feels like to create something without an audience or expectations, and the magic of finding your flow in writing.

Nathana Gilson: I was thinking about the idea that “being in your 20s is just going back to liking everything you liked when you were 13 but without being ashamed.” In Girls Against God, the unnamed narrator matures from a God-hating teen to a full-grown witch. I was wondering how much you were thinking about self-censorship and actively rebelling against that urge as you were working on the book?

Jenny Hval: I think this depends on how old you are. In my 20s, I would have agreed with this comment. But, actually, I was still ashamed—I was just more amused about it. My 30s were better: I admitted to liking things a lot more than I did in my 20s.

Girls Against God is definitely about rethinking self-censorship and about the exploding joy of not censoring writing motivated by rage and ecstasy. But it’s even more about how we’re taught self-censorship—in school, at university, in any kind of institution or hierarchy. For example, by toning down or correcting rebellious ideas, disguising the act of reduction as something like “impulse control,” or for that matter, “quality,” “literary canon,” “high art/low art” etc., etc. There’s a line in the book that points out: “Maybe the only way an artist can escape capitalism and patriarchy today is to use art to disappear as an individual.” The narrator insists that the artist’s person, ego, and body must disappear for something new to start.

When you started to become interested in making a career of art, who did you look to, or feel inspired by, for proof that art could be in service of something bigger than self-promotion?

I am not sure I think that art can, and I don’t think I ever will be. I am very ambiguous about being an artist at a time when so much is about, or in service of, promotion and money.

When I started out, I was much more interested in performance art than playing music on stage. I was studying writing, theatre, and performance art subjects at the time—but I also enjoyed the simplicity and down-to-earth nature of playing songs on an acoustic guitar in a bar for nothing and nobody. There was no money, no audience, no expectations. It was interesting as a completely hollow experience in a sort of “if a tree falls in the forest” kind of way.

I did this for a long time—first in Melbourne, where I was living, playing in bands that had a very, very small audience [and] later (just as the audience of my Australian band was growing!) I started over back in Oslo, when I moved back there, playing solo to almost no one, again. And then I did it some more in other countries, because hardly anyone had heard of me outside of my own country, for years.

I am not presenting a “paid my dues” kind of argument here, but I’m thinking about this experience of empty rooms and low expectations a lot these days when art is nowhere to be seen except in passing or in the past, as abandoned venues, empty theatres, or dirty, tagged-over murals at a subway station. Was there ever anything there in the first place? And would I have been interested in any kind of artistic manifestations if I hadn’t done this long period of playing for virtually nobody? I don’t think I, as a person, could have done this—writing, performing—if it hadn’t been so far underground.

You moved to Australia to study creative writing and performance after growing up in Norway. How was Australia different from where you grew up? What do you remember of that period in your life?

Things were very different from my experiences in Norway, as well as strangely similar (because I was a white, English-speaking person from a rich, Western country). It was easy for me to be a bit invisible. I really thought I could reinvent myself with a new language and a new hope in a new town.

The biggest difference, perhaps, was the relationship with “the world” when it came to art. I felt like in Norway, we were longing for Europe, or even just Sweden, longing to belong or to connect. I read French, British, Swedish, Danish, and German writers, and I felt like I was close.

In Australia, I felt like the art histories I knew were remote, and artists knew they were on the edge of the world (as my friend and wonderful artist Laura Jean Englert writes in her song “Australia”: “Here upon this artless wedge / We struggle not to fall off the edge of the world”).

I also met an awareness of being on stolen land (obviously this was in a specific and very liberal political bubble of my university—sadly not the opinion of the majority). I think this changed my entire worldview, for which I am extremely grateful.

In the novel, magic is seen as a way of dismantling power structures. How can artists reject conservatism in environments where upholding it is still celebrated?

Well, I guess, ideally, we should abandon those environments? But who can afford to, apart from the most privileged people? Because we depend on these spaces, we can’t, and then we’re stuck there. Unless we’re not even accepted in them ... which, I guess, most people aren’t. We are stuck in structures that we depend on and want to reject all at once. I have met so many music-industry people who on some level or another hate the industry, yet kind of thrive in it. This is why I always wonder if there is any meaning to it all. I have no good answer, but hopefully exploring ambiguity has some meaning.

2020 was a strange year for so many of us. I wonder how your attitude to productivity and self-expression changed, as what you may have considered normal began to disappear?

I tried to be productive, but I was just writing to exist. Then I gave up being productive and got a dog (which I have wanted to for 20 years), which was much more exciting. It was my year of being forced into being just a private person. I no longer felt like I had any other identity. Is that what we call “normal”?

Now I find that I do creative stuff that I like more again, but I hardly have time for anything because I have a demanding, loud puppy.

You’ve mentioned in the past that language can feel very violent: a physical act. How someone’s native language can feel like it’s fighting with all the new languages they’re expected to keep up with. When working on this novel, how did you feel about obeying expectations like common sense, logic, or structure?

I felt quite liberated. I think the anger of the protagonist felt very relaxing. I mean, feeling like I could finally write in my own language and not think so much about form and logic, I felt like I allowed myself to get into the flow of writing. Maybe that is one interpretation of magic?

Edvard Munch has a big presence in this novel. What was your interest in his art, or legacy?

I’ve never been particularly interested in Munch. He has just been a presence in my life because he is my country’s One Big Visual Artist, a bit like how Grieg is our One Big Composer, or A-ha used to be our One Big Pop Band. So, Munch has been a godlike figure during my school years.

I guess the connection to black metal intrigued me when I finally nerded my way into listening to a lot of the classic black metal albums a few years back. There was something about the presentation of the young male figure in the artwork (usually involving corpse paint, a young male figure turned away from—and by—society; the unhealthy, sort of blackened, outsider), and in the music, that was very striking.

How do your other lives—as a musician, songwriter, journalist, art critic—inform your novel writing process?

I mostly do music 100 percent. I haven’t done a single piece of journalism in nearly 10 years, simply because there is no time. So, I just feel like a musician that also writes on the side. Usually whatever I write of prose ends up as a better song. I wrote a lot last year, but abandoned the manuscript ... Now I’ve condensed 100 pages of prose down into something like four pages of lyrics. And it’s better that way.

Perhaps what I’m trying to say is that I just feel like a musician with a literary interest, who occasionally ventures into an extended piece of text. The more this other text is informed by my musical experience and stage experience, the better it turns out. And I feel lucky to be able to do this.

How can writers growing up with the noise of the internet better listen to their inner dialogue or follow their own intuition?

I don’t know ... turn off the internet. Or dive deep into it for a while, but come up for air. You can’t breathe down there.